Lochner v. New York (1905) - Northern Illinois University

advertisement

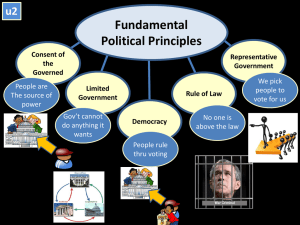

Substantive Due Process: The Rise and Demise of Liberty of Contract Artemus Ward Dept. of Political Science Northern Illinois University aeward@niu.edu Police Power • What is the “police power”? • The inherent authority of the state to act to protect the health, safety, morals, and general welfare of the people. • Examples of the police power are best seen in criminal law which is enacted by states to protect its people: murder, motor vehicle regulation, alcohol and drug laws, etc. • While the federal government may limit certain forms of state police power under the U.S. Constitution, the federal government does not possess a general police power the way that states do. • The federal government’s powers are limited and defined by the Constitution • One of the ways that state police power is limited is through the Constitution’s guarantee of due process. Magna Carta (1215) • What is due process? • The concept emanates from the Magna Carta (1215) where the Lords sought formal legal protection from arbitrary treatment by the King: • “No free man shall be seized or imprisoned, or stripped of his rights or possessions, or outlawed or exiled, or deprived of his standing in any other way, nor will we proceed with force against him, or send others to do so, except by the lawful judgment of his equals or by the law of the land.” • The phrase due process of law first appeared in a statutory rendition of Magna Carta in 1354 during the reign of Edward III of England, as follows: “No man of what state or condition he be, shall be put out of his lands or tenements nor taken, nor disinherited, nor put to death, without he be brought to answer by due process of law.” Procedural v. Substantive Due Process • Both the 5th and the 14th Amendments to the U.S. Constitution contain a Due Process Clause. • The 5th states: “nor shall any person…be deprived of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” • The 14th states: “nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” • What does this mean? • Procedural Due Process – guarantees individuals a fair and impartial legal process in criminal and civil matters (e.g., the right to sufficient notice, the right to an impartial arbiter, the right to give testimony and admit relevant evidence at hearings, etc.). • Substantive Due Process – protects individuals against majoritarian policy enactments which exceed the limits of governmental authority (i.e., a majority’s enactment is not law, and cannot be enforced regardless of how fair the process of enforcement actually is). Substantive Due Process Origins • Though courts had discussed the substantive component of due process (without using the phrase) prior to the Civil War, it was Chief Justice Robert Taney’s opinion in Dred Scott v. Sanford (1857) that most point to as originating the concept in American constitutional law. • He declared the Missouri Compromise unconstitutional because “An act of Congress which deprives a citizen of the United States of his liberty or property [a slave], merely because he came himself or brought his property into a particular Territory…could hardly be dignified with the name of due process of law.” The Slaughter-House Cases (1873) • • • • Following the passage of the 14th Amendment (1868), the Court decided the Slaughter-House Cases (1873). New Orleans butchers were dumping animal waste in the city’s water supply and the state passed a law regulating slaughtering – forcing butchers to slaughter their animals at a central location away from water supplies. The butchers argued that the newly enacted 14th Amendment protected their “liberty” to conduct their business affairs without state encroachment. Writing for the 5-4 majority, Justice Samuel Miller took a narrow view of the 14th Amendment and ruled that it did not restrict the police powers of the state. With regard to the Due Process Clause, the Court held: “Under no construction of that provision that we have ever seen, or any that we deem admissible, can the restraint imposed by the state of Louisiana upon the exercise of their trade by butchers of New Orleans be held to be a deprivation of property within the meaning of that provision.” Yet the dissenters, led by Justice Stephen J. Field, said that the 14th Amendment protected individual rights such as the “liberty” or freedom to pursue an economic occupation. Field’s dissent would become influential over time. The Rise of Substantive Due Process • The theory of substantive due process slowly gained traction. • Thomas M. Cooley published his influential treatise Constitutional Limitations (1868), which elevated the word “liberty” within the due process clause to the status of an important constitutional right that would serve as a mechanism for protecting property rights and for restricting government regulation. By 1890 it was in its 6th edition. • Herbert Spencer was an influential theorist who promoted social Darwinism—the idea that government should merely maintain order and property rights and the “fittest” would survive and succeed. His book Social Statics (1851) and other works would prove influential at the end of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Munn v. Illinois (1877) • • • • In Munn, the Court began encouraging substantive due process arguments. The Court upheld the state regulation—in this case a state regulatory board to fix maximum rates grain elevators could charge farmers and merchants—but instead of foreclosing any substantive due process claims the way the Court had done in Slaughter-House, the Court said that in some cases such regulations could be struck down. Specifically, in his majority opinion Chief Justice Morrison Waite said it depended on the nature of the regulation: “We find that when private property is ‘affected with a public interest it ceases to be [of private right] only.’” This doctrine came to be known as the business-affectedwith-a-public-interest doctrine (BAPI). The Court used it in Munn to reason that the grain elevator business played a crucial role in the distribution of food stuffs to the nation and was therefore an industry that was affected with the public interest and subject to regulation. In dissent, Justice Stephen J. Field railed against the test: “There is hardly an enterprise or business engaging the attention and labor of any considerable portion of the community, in which the public has not an interest in the sense in which that term is used by the court.” Mugler v. Kansas (1887) • The Court considered a state law that prohibited the manufacture and sale of liquor. Although the majority upheld the regulation against a substantive due process challenge, the Court’s opinion, written by Justice John Marshall Harlan I represented something of a break with Munn. • First, it articulated a view that not “every statute enacted ostensibly for the promotion of [the public interest] is to be accepted as a legitimate exertion of police powers of the state.” • Second, the Court suggested it would carefully scrutinize state action: “There are…limits beyond which legislation cannot rightfully go…. If, therefore, a statute purporting to have been enacted to protect the public health, the public morals, or the public safety, has no real or substantial relation to those objects, or is a palpable invasion of rights secured by the fundamental law, it is the duty of the courts to so adjudge, and thereby give effect to the Constitution.” Chicago, Milwaukee & St. Paul Railway v. Minnesota (1890) • • • • • For the first time, the justices struck down a state regulation on the ground that it interfered with due process guarantees. The state established a commission to set railroad rates for transportation of goods and for warehouse storage. The railroad argued that the commission had interfered with “its property” without providing due process of law. Writing for the majority, Justice Samuel Blatchford held for the railroad on both procedural and substantive due process grounds. He examined the law in terms of the reasonableness standard set forth in Mugler: “The question of the reasonableness of a rate of charge for transportation by a railroad company…is eminently a question for judicial investigation, requiring due process of law for its determination.” He found that the law deprived the company of its property in an unfair way: “If the company is deprived of the power of charging reasonable rates…and such deprivation takes place in the absence of an investigation by judicial machinery, it is deprived of the lawful use of its property, and thus, in substance and effect, of the property itself, without due process of law.” In the 14 years since Slaughter-House, the Court had moved from a refusal to inject substance into the due process to a near affirmation of the doctrine of substantive due process. Allgeyer v. Louisiana (1897) • • • • With the alleged purpose of preventing fraud, the state enacted a law that barred its citizens and corporations from doing business with outof-state insurance companies, unless they complied with a specified set of requirements. Among those requirements were stipulations that the out-of-state company must establish as place of business in the state and must have an authorized agent inside the state. Justice Rufus Peckham, writing for a unanimous Court, held the state law unconstitutional on substantive due process grounds: "The 'liberty' mentioned in [the Fourteenth] amendment means not only the right of the citizen to be free from the mere physical restraint of his person, as by incarceration, but the term is deemed to embrace the right of the citizen to be free in the enjoyment of all his faculties, to be free to use them in all lawful ways, to live and work where he will, to earn his livelihood by any lawful calling, to pursue any livelihood or avocation, and for that purpose to enter into all contracts which may be proper, necessary, and essential to his carrying out to a successful conclusion the purposes above mentioned.“ In just under 25 years, business interests had pushed the Court rejecting substantive due process to accepting it and equating it with a fundamental right to liberty of contract. Holden v. Hardy (1898) • • • • The Court examined a Utah law prohibiting companies engaged in the excavation of mines from working their employees more than 8 hours in a day, except in emergency situations. Attorneys challenging the law claimed: “It is…not within the power of the legislature to prevent persons who are…perfectly competent to contract, from entering into employment and voluntarily making contracts in relation thereto merely because the employment…may be considered by the legislature to be dangerous or injurious to the health of the employee; and if such right to contract cannot be prevented, it certainly cannot be restricted by the legislature to suit its own ideas of the ability of the employee to stand the physical and mental strain incident to the work.” The state asserted that the challenged statute was a “health regulation” and within the state’s power because it was aimed at “preserving to a citizen his ability to work and support himself.” The Supreme Court, in an opinion by Justice Henry Brown, reiterated its Mugler position: “The question in each case is whether the legislature has adopted the statute in exercise of a reasonable discretion or whether its actions be a mere excuse for an unjust discrimination.” The Court deemed the regulation “reasonable”; that is it did not impinge on the liberty of contract because the state had well justified its interest in protecting miners from their jobs’ unique health problems and dangerous conditions. Lochner v. New York (1905) The Facts • • • • • In New York in the late 1800s, bakers were paid by the day, not by the hour. $2 per day was a typical wage. Unsurprisingly, bakers favored shorter work days, as they assumed that they would continue to receive their current pay levels whether they worked 10 hours or they worked 14 hours. They also believed that long work hours increased their risk of developing various lung diseases. A bill, supported by bakers, to reduce the workday for bakers to 10 hours was narrowly defeated in the New York Assembly in 1887. By the mid-1890s, larger bakeries in New York were unionized and generally adopted 60-hour work weeks. The large bakeries, however, faced competition from smaller bakeries which demanded longer hours from their employees (the employees often were required to sleep in or near the bakeries). Lochner’s Home Bakery Utica, New York Lochner v. New York (1905) The Facts • • • • • While unionized bakers continued to lobby for a ten-hour law, a muckraking New York Press reporter published stories about unsanitary conditions in smaller bakeries, including accounts of finding open sewers and cockroaches on baking utensils. A state factory inspector's report confirmed that conditions were unsanitary and led to growing public support for a law regulating bakeries. The state legislature passed the Bakeshop Act of 1897. It included sections regulating sanitary conditions (e.g., no sleeping in a bake room) and a section strongly supported by the baker's union, establishing the 60-hour maximum hour maximum work week for bakers. Utica bakery owner Joseph Lochner had a longstanding dispute with the baker's union. Union officials persuaded state factory inspectors to file a complaint against Lochner for employing a baker named Aman Schmitter for more than sixty hours in one week. In February 1903, Lochner was tried but offered no defense. He was found guilty of violating the Bakeshop Act and sentenced to pay a fine of $50. Joseph Lochner • • • The original U.S. Senate Chamber in the Capitol became available when the Senate moved into its current chamber in 1861. When the Senators moved out, the U.S. Supreme Court moved in. The Court met in the old Senate Chamber from 1861 until they received their own building in 1935. This photo shows the old Senate Chamber converted for the Supreme Court. Notice the Ladies wearing hats in the gallery as staff prepare for the justices, who decided Lochner, to take the bench. Lochner v. New York (1905) Justice Rufus Peckham delivered the 5-4 majority opinion • • • “The statute necessarily interferes with the right of contract between the employer and employees, concerning the number of hours in which the latter may labor in the bakery of the employer. The general right to make a contract in relation to his business is part of the liberty of the individual protected by the 14th Amendment of the Federal Constitution. Under that provision no state can deprive any person of life, liberty, or property without due process of law. The right to purchase or to sell labor is part of the liberty protected by this amendment, unless there are circumstances which exclude the right.” “To the common understanding, the trade of a baker has never been regarded as an unhealthy one….. “Clean and wholesome bread does not depend upon whether the baker works but ten hours per day or only sixty hours a week.” Peckham explained that under a broad understanding of the police powers of the state (to protect the health, safety, welfare, and morals of the people) anything could be regulated: “Not only the hours of employees, but the hours of employers, could be regulated, and doctors, lawyers, scientists, all professional men, as well as athletes and artisans, could be forbidden to fatigue their brains and bodies by prolonged hours of exercise, lest the fighting strength of the state be impaired.” Lochner v. New York (1905) Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. Dissenting • • • “This case is decided upon an economic theory which a large part of the country does not entertain. If it were a question whether I agreed with that theory, I should desire to study it further and long before making up my mind. But I do not conceive that to be my duty, because I strongly believe that my agreement or disagreement has nothing to do with the right of a majority to embody their opinions in law. It is settled by various decisions of this court that state constitutions and state laws may regulate life in many ways which we as legislators might think as injudicious, or if you like as tyrannical, as this, and which, equally with this, interfere with the liberty to contract.” “The 14th Amendment does not enact Mr. Herbert Spencer's Social Statics.” “Some of these laws embody convictions or prejudices which judges are likely to share. Some may not. But a Constitution is not intended to embody a particular economic theory, whether of paternalism and the organic relation of the citizen to the state or of laissez faire. It is made for people of fundamentally differing views, and the accident of our finding certain opinions natural and familiar, or novel, and even shocking, ought not to conclude our judgment upon the question whether statutes embodying them conflict with the Constitution of the United States.” National Consumer’s League • Calls for improved working conditions for women and children began to pick up steam around the nation. • The organization most responsible for change, and for the Court again addressing issues of gender, was the National Consumer’s League (NCL). • Through the work of its national staff and numerous affiliates, the NCL secured maximum-hour or other restrictions on night work for women in 18 states. • The NCL asked Louis Brandeis, the brother-in-law of one of the organization’s most active members and already a famous progressive lawyer, to take the case of Muller v. Oregon (1908). • Brandeis agreed but under one condition—that he have sole control over the litigation—Oregon agreed and allowed the NCL (and Brandeis) to represent the group in Court. Louis Brandeis “Brandeis Brief” (1908) • Brandeis knew that in order to win the case, he would have to present information to show that the dangers to women working more than 10 hours a day made them more deserving of state protection than the bakers in Lochner, and by proving that there was something different about women that justified an exception to the freedom of contract doctrine. • NCL researchers compiled information about the possible detrimental effects of long work hours on women’s health and morals, as well as on the health and welfare of their children, including t heir unborn children. • Brandeis stressed women’s differences from men and the reasonableness of the state’s legislation (low-level scrutiny). • In fact, the brief had only 3 pages of legal argument and 110 pages of sociological data culled largely from European studies of the negative effects of long hours of work on women’s health and reproductive capabilities. • Some examples… “Brandeis Brief” (1908) • “The leading countries in Europe in which women are largely employed in factory or similar work have found it necessary to take action for the protection of their health and safety and the public welfare, and have enacted laws limiting the hours of labor for adult women…” • “Twenty states of the Union…have enacted laws limiting the hours of labor for adult women…. In no state has any such law been held unconstitutional, except in Illinois…” • Brandeis provided reports such as: • “Report of Select Committee on Shops Early Closing Bill, British House of Commons, 1895” where a doctor describes the deterioration of the health of women who work long hours. • “Report of the Maine Bureau of Industrial and Labor Statistics, 1888” where a doctor described the adverse effects of standing for 8-10 hours a day – linking it with infant mortality rates. • Should judges consider such information? Muller v. Oregon (1908) • • • • • • • What are the facts? A 1903 Oregon law said “That no female (shall) be employed in any mechanical establishment, or factory, or laundry in this state more than ten hours during any one day. The hours of work may be so arranged as to permit the employment of females at any time so that they shall not work more than ten hours during the twenty-four hours of any one day.” A violation of the provision resulted in a misdemeanor subject to a fine of not less than $10 nor more than $25. The state brought charges against Curt Muller, a laundry owner, for violating the statute. A trial resulted in a verdict against the defendant, who was sentenced to pay a fine of $10. The Supreme Court of the state affirmed the conviction and Muller challenged the law under liberty of contract. Justice David Brewer delivered the unanimous opinion. Does the Court mention the Brandeis Brief? “It may not be amiss, in the present case, before examining the constitutional question, to notice the course of legislation, as well as expressions of opinion from other than judicial sources. In the brief filed by Mr. Louis d. Brandeis for the defendant…is a very copious collection of all these matters.” Muller v. Oregon (1908) • • • Should the Court consider the kind of sociological and medical data included in the brief or should it just stick to the law? Justice Brewer said that the data is not controlling, the law is, but the Court can consider this information to help understand the facts: “The legislation and opinions referred to in the margin may not be, technically speaking, authorities, and in them is little or no discussion of the constitutional question presented to us for determination, yet they are significant of a widespread belief that woman’s physical structure, and the functions she performs in consequence thereof, justify special legislation restricting or qualifying the conditions under which she should be permitted to toil. Constitutional questions, it is true, are not settled by even a consensus of present public opinion, for it is the peculiar value of a written constitution that places in unchanging form limitations upon legislative action, and thus gives a permanence and stability to popular government which otherwise would be lacking. At the same time, when question of fact is debated and debatable, and the extent to which a special constitutional limitation goes in affected by the truth in respect to that fact, a widespread and long continued belief concerning it is worthy of consideration. We take judicial cognizance of all matters of general knowledge.” • • • • Muller v. Oregon (1908) What does the Court say about liberty, freedom of contract? It is not absolute and must be balanced against the police power of the state: “It is undoubtedly true, as more than once declared by this court, that the general right to contract in relation to one’s business is part of the liberty if the individual, protected by the 14th Amendment to the Federal Constitution; yet it is equally well settled that this liberty in not absolute and extending to all contracts, and that a state may, without conflicting with the provisions of the 14th Amendment, restrict in many respects the individual’s power of contract.” What does the Court say about women? What is their role in society? They have special roles as child-bearers and therefore can be protected: “That woman’s physical structure and the performance of maternal functions place her at a disadvantage in the struggle for subsistence is obvious. This is especially true when the burdens of motherhood are upon her. Even when they are not, by abundant testimony of the medical fraternity continuance for a long time on her feet at work, repeating this from day to day, tends to injurious effects upon the body, and, as healthy mothers are essential to vigorous offspring, the physical well-being of woman becomes an object of public interest and care in order to preserve the strength and vigor of the race.” Muller v. Oregon (1908) • What does the Court say about the differences between men and women? Is there justification for special legislation that targets women but not men? • “History discloses the fact that woman has always been dependent upon man. He established his control at the outset by superior physical strength… (which) has continued to the present…. It is impossible to close one’s eyes to the fact that she still looks to her brother and depends on him…. The two sexes differ in structure of body, in the functions to be performed by each, in the amount of physical strength, in the capacity for long continued labor, particularly when done standing, the influence of vigorous health upon the future well-being of the race, the self-reliance which enables one to assert full rights, and in the capacity to maintain the struggle for subsistence. This difference justifies a difference in legislation, and upholds that which is designed to compensate for some of the burdens which rest upon her.” Muller v. Oregon (1908) • Does the Court mention the fact that women cannot vote in Oregon? • Yes, but it doesn’t matter: “We have not referred in this discussion to the denial of elective franchise in the state of Oregon, for while that may disclose a lack of political equality in all things with her brother, that is not of itself decisive. The reason runs deeper, and rests in the inherent difference between the two sexes, and in the different functions in life which they perform.” • Do they overturn Lochner? • No. They distinguish it: “For these reasons, and without questioning in any respect the decision in Lochner v. New York, we are of the opinion that it cannot be adjudged that the act in question is in conflict with the Federal Constitution, so far as it respects the work of a female in a laundry, and the judgment of the Supreme Court of Oregon is affirmed.” Muller’s Progeny • Muller had an immediate effect. State courts began to hold other forms of protective legislation for women constitutional, whether or not they involved the kind of 10-hour maximums at issue in Muller. • Thus, 8-hour maximum work laws in a variety of professions, outright bans on night work for women, and minimum-wage laws for women were routinely upheld under the Muller rationale. • Much of this Court-sanctioned governmental protection, however, worked to keep women out of high-paying evening jobs or positions that they desperately needed to support their families. Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire (1911) Youtube clip: PBS, New York – 4 (36 min.) Power to the People @ 1:07:56 – 1:44:08 • • • • Women began attending college in higher numbers and entering the workforce out of necessity. Young women, especially immigrants, were confined to low-paying jobs in substandard conditions. The Triangle Shirtwaist Factory Fire in New York City put the issue on the national agenda. In its wake, New Yorkers demanded and the legislature passed laws protecting workers from dangerous working conditions. Suffragists Parade Down Fifth Avenue (1917). Advocates march in October 1917, displaying placards containing the signatures of over one million New York women demanding to vote. Stettler v. O’Hara (1917): Brandeis Joins the Court • • • • • • The NCL’s efforts to protect women from unscrupulous employers were victorious in the Supreme Court in several additional cases, but then ran into trouble in the early 1920s. In Stettler v. O’Hara (1917) a lower court decision upholding Oregon’s minimum-wage law for women was appealed to the Supreme Court. Conservatives argued that freedom of contract and Lochner were controlling. Brandeis was again hired and he filed another brief explaining how a living wage was essential to the health, welfare, and morals of women. But before the Supreme Court could decide the case, Brandeis was appointed to it! The case was reargued and the justices split 4-4 with Brandeis not participating, thus sustaining the lower court decision. Louis Brandeis Bunting v. Oregon (1917) • • • • • The next NCL sponsored case, Bunting v. Oregon (1917) attracted significant attention. Brandeis’ hand-picked successor as counsel for the NCL, Felix Frankfurter, used the same kinds of arguments Brandeis had used in Muller and Stettler. The state law said that “no person shall be employed in any mill, factory, or manufacturing establishment in this state more than 10 hours in any one day.” In a 5-3 decision, again with Brandeis not participating, the Court extended Muller to uphold the law. Writing for the majority, Justice Joseph McKenna did not even mention Lochner and explained: although Bunting contended that “the law…is not either necessary or useful ‘for the preservation of the health of employees’,” no evidence was provided to support that contention. Moreover, the judgment of the Oregon legislature and supreme court was that “‘It cannot be held, as a matter of law, that the legislative requirement is unreasonable or arbitrary.” McKenna concluded, therefore, that no further discussion was “necessary” and upheld the law. th 19 Amendment (1920) • Although the NCL was victorious in Muller and Bunting, it did not anticipate the effect that the controversy within the suffrage movement would have on pending litigation. • In 1920, the movement was successful in overturning Minor v. Happersett (1875) by passing the 19th Amendment granting women the right to vote—50 years after the 15th Amendment guaranteed voting rights to African-American males. The National Woman’s Party and an Equal Rights Amendment • Once the 19th was ratified, attempts were made to secure other rights for women. • Women in the more radical branch of the suffrage movement, represented by the National Woman’s Party (NWP), proposed the addition of an equal rights amendment to the Constitution. • Progressives and those in the NCL were horrified because they believed that an equal rights amendment would immediately overturn Muller and Bunting and invalidate all the protective legislation they had lobbied so hard to enact. Alice Paul: Co-founder NWP Adkins v. Children’s Hospital (1923) • • • • • • • When Adkins came to the Court, the NCL was ready. Adkins involved the constitutionality of a Washington, DC minimum wage law for women. The NWP filed an amicus brief urging the Court to rule that, in light of the 19th Amendment, women should be viewed on a truly equal footing with men. The division among women between equal rights and protective legislation was now exposed to public view and was a debate resurrected again and again both in the Court and in public discourse— and continues to this day. Many thought the Court had essentially overruled Lochner in the Bunting decision, which upheld limits on factory and mill workers. Yet in Adkins, the Court seemed to resurrect Lochner, ruling 5-4 that minimum wage laws for women were an unconstitutional violation of liberty of contract. But the Court did not overturn Muller and Bunting, choosing instead to distinguish them. In dissent, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr. noted that the term “due process of law” had now evolved into the “dogma, Liberty of Contract.” It was obvious to many that the Court had been influenced by the passage of the 19th Amendment and the pro-equality arguments of the NWP. But the Court has also been transformed by a number Republican appointments that turned the tide solidly in favor of liberty of contract. Meyer v. Nebraska (1923) Pierce v. Society of Sisters (1925) • • • • The Court also applied the doctrine of substantive due process to regulations outside of business. In Meyer, the justices considered a state law, enacted after WWI, that forbade schools to teach German and other foreign languages to students below 8th grade. In an opinion by Justice James McReynolds, the Court struck down the law reasoning that the word “liberty” in the 14th Amendment covers “the right of the individual…to engage in any of the common occupations of life, to acquire useful knowledge, to marry, establish a home and bring up children, to worship God according to the dictates of his own conscience, and generally to enjoy those privileges long recognized at common law as essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness by free men.” According to the Court, government cannot interfere with these liberties, “under the guise of protecting the public interest, by legislative action which is arbitrary or without reasonable relation to some purpose within the competency of the State to that effect.” In Pierce, the Court again invoked substantive due process to strike down a state law that mandated public education for children, including those who had been attending religious schools. Writing for the majority, Justice James McReynolds reasoned that parents have the primary responsibility for their children’s education and therefore have the “liberty” to choose where and how to obtain it. The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse • Four conservative justices (l-r George Sutherland, Willis Van Devanter, James McReynolds, and Pierce Butler - the so-called "Four Horseman of the Apocalypse") insisted that the Constitution protected the "liberty of contract.“ They were in the majority in Adkins and helped to strike down numerous pieces of economic legislation (including minimum wage laws and FDR's "New Deal" programs such as the National Industrial Recovery Act) in the 1920s and early 1930s. Nebbia v. New York (1934) • • • In Nebbia, the New York legislature created the Milk Control Board with the power to fix minimum and maximum prices stores could charge consumers for milk. Nebbia was a store owner who claimed the 14th Amendment’s Due Process Clause protected his right to conduct his business as he saw fit. New York countered with an extensive study showing that milk was essential to public health and could therefore be regulated. The Court upheld the law 5-4. Justice Owen Roberts said: “The due process clause makes no mention of sales or of prices any more than it speaks of business or contracts or buildings or other incidents of property.” He noted the problems associated with leaving milk to market competition: prices are lowered and the dairy farmer cannot survive, thereby jeopardizing the availability of milk for consumers. In dissent, Justice James McReynolds noted that the Court had never allowed price controls and that this case would allow states to fix prices for farm products, groceries, shoes, clothing, and all necessities of modern civilization, as well as labor: “Not only does the statute interfere arbitrarily with the rights of the little grocer to conduct his business according to standards long accepted—complete destruction may follow; but it takes away the liberty of 12,000,000 consumers to buy a necessity of life in an open market….To him with less than 9 cents it says: You cannot procure a quart of milk from the grocer although he is anxious to accept what you can pay and the demands of your household are urgent!” Morehead v. New York ex rel. Tipaldo (1936) • • • Was liberty of contract dead? In Morehead, the Court considered a 1933 minimum wage law that “declared it to be against public policy for any employer to employ any woman at an oppressive and unreasonable wage.” It defined as unreasonable a wage that was “both less than the fair and reasonable value of the services rendered and less than sufficient to meet the minimum cost of living necessary for health.” Women could file complaints with a state board. Tipaldo owned a laundry and paid his employees $7-$10 per week even though the board had set $12.40 as a minimum wage. The radical NWP supported Tipaldo and argued that the New York law was unconstitutional on Equal Protection grounds because it treated the sexes differently. However, the moderate NCL defended the law. This time, Justice Own Roberts sided with the four conservatives and they struck down the law 5-4. Writing for the majority, Justice Pierce Butler was emphatic: “Freedom of contract is the general rule and restraint is the exception.” Migrant Mother With Children, California - 1936. Resettlement Administration. FDR’s Court Packing Plan • • • Morehead was widely criticized by both liberals and conservatives who sympathized with the plight of women and children workers. Even the Republican Party’s 1936 platform included support for minimum wage and maximum hour statutes. Roosevelt increased pressure on the justices by proposing to enlarge the size of the Court and thus, through his new appointees, win more favorable decisions. Both Republicans and Democrats were outraged by this attack on the court's independence and forced Roosevelt to withdraw his proposal. No president since has attempted to directly undermine the court's constitutional autonomy, and the size of the court has remained fixed (since 1869) at nine justices. This cartoon by Elderman appeared in the February 6, 1937, Washington Post. West Coast Hotel v. Parrish (1937) • • • The Court abandoned the liberty of contract doctrine, explicitly overruled Adkins, and upheld a minimum-wage law for women. Chief Justice Charles Evans Hughes explained that the entire area of the law should be re-examined because of the “economic conditions which have supervened”: “There is an additional and compelling consideration which recent economic experience has brought into a strong light. The exploitation of a class of workers who are in an unequal position with respect to bargaining power and are thus relatively defenceless against the denial of a living wage in not only detrimental to their health and well being but casts a direct burden for their support upon the community. What these workers lose in wages the taxpayers are called upon to pay. The bare cost of living must be met. We may take judicial notice of the unparalleled demands for relief which arose during the recent period of depression and still continue to an alarming extent….The community is not bound to provide what is in effect a subsidy for unconscionable employers. The community may direct its law-makinig power to correct the abuse which springs from their selfish disregard of the public interest.” West Coast Hotel v. Parrish (1937) • In dissent, Justice George Sutherland reiterated the liberty of contract doctrine and accused the majority of judicial activism: • “The meaning of the Constitution does not change with the ebb and flow of economic events.” • “The judicial function is that of interpretation; it does not include the power of amendment under the guise of interpretation.” • “If the Constitution, intelligently and reasonably construed in the light of these principles, stands in the way of desirable legislation, the blame must rest upon that instrument, and not upon the Court for enforcing it according to its terms. The remedy in that situation—and the only true remedy—is to amend the Constitution.” • After this case, the Court never again invoked “liberty of contract” to strike down a government economic regulation. Where FDR’s Court-packing bill failed, legislation making retirement more attractive succeeded. The 1937 Retirement Act allowed Supreme Court justices to retire in “senior status” and sit on lower federal courts when designated by the Chief Justice of the United States. Van Devanter was the first justice to take advantage of this provision. Finally “Packing” the Court • • • • • • • • • • • In subsequent terms, all of Van Devanter’s colleagues (except for Owen Roberts) departed under FDR. In the end, President Roosevelt appointed nine Justices to Court, more than any other President except George Washington, who appointed eleven. By 1941, eight of the nine Justices were Roosevelt appointees. Hugo Black – 1937 Stanley F. Reed – 1938 Felix Frankfurter – 1939 William O. Douglas – 1939 Frank Murphy – 1940 Harlan Fiske Stone (Chief Justice) – 1941 James F. Byrnes – 1941 Robert H. Jackson – 1941 Wiley Rutledge – 1943 • • • • Aftermath By United States v. Darby Lumber (1941) the Court unequivocally upheld Congress’s authority to pass the federal Fair Labor Standards Act, which regulated maximum hours and minimum wages for ALL workers and is still in effect today. By Williamson v. Lee Optical (1955) the Court was unanimously upholding state regulations of economic matters under the rational basis test. In Williamson, a state law regulated optical care by allowing ophthalmologists and optometrists to examine eyes, write prescriptions, and fit glasses but not opticians who could only grind lenses and fill prescriptions. Writing for the Court Justice William O. Douglas explained that the Court should not use the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment to strike down state laws, regulatory of business and industrial conditions, because they may be unwise. He said: “The law need not be in every respect logically consistent with its aims to be constitutional. It is enough that there is an evil at hand for correction, and that it might be thought that the particular legislative measure was a rational way to correct it.” Finally, he said that if the people don’t like the laws that are passed, they can resort to the polls. For a time, it appeared that substantive due process was dead. Yet, in the 1960s, however, the liberal justices who had agreed that economic substantive due process (liberty of contract) was no longer good law divided over another aspect of substantive due process: personal privacy. Griswold v. Connecticut (1965) • • • • In Griswold, the Court was asked to strike down a state law that banned the distribution of contraceptives on the ground that the statute violated the right to privacy. Yet there is no provision of the Constitution that explicitly guarantees a right of privacy. The Court struck down the law and declared that the Constitution did indeed protect privacy rights, but the justices did not agree on which section of the Constitution required that conclusion. Writing for the majority, Justice Douglas said that various specific provisions gave rise to zones of privacy. Some argued that privacy rights are embedded in the Due Process Clause of the 14th Amendment. Justice John Marshall Harlan II asserted this substantive due process approach to privacy in his concurring opinion: “In my view, the proper constitutional inquiry in this case is whether this Connecticut statute infringes the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment because the enactment violates basic values ‘implicit in the concept of ordered liberty.’…The Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment stands, in my opinion, on its own bottom.” Justice Hugo Black thought Harlan and the other justices in the majority had gone too far and wrote in dissent: “I like my privacy as well as the next one, but I am nevertheless compelled to admit that government has a right to invade it unless prohibited by some specific constitutional provision.” From Privacy to Liberty • • • • In the years after Griswold, the Court used the due process approach to privacy to expand a number of liberties. Most notable was Roe v. Wade (1973) that established the right to abortion. Writing for the majority, Justice Harry Blackmun said: “[The] right of privacy, whether it be founded in the Fourteenth Amendment’s concept of personal liberty and restrictions upon state action, as we feel it is, or [another clause]…is broad enough to encompass a woman’s decision whether or not to terminate her pregnancy.” The Court has reached similar conclusions in other areas of privacy but has dropped using the controversial “right to privacy” language in favor of the phrase “liberty interest”: In Cruzan v. Dir. Missouri Dept. of Health (1990) the justices held that “the principle that a competent person has a constitutionally protected liberty interest in refusing unwanted medical treatment may be inferred from our prior decisions.” In Lawrence v. Texas (2003) the Court concluded that laws criminalizing consensual sodomy were barred by the “liberty” provision of the 14th Amendment’s Due Process Clause. The Essential Fairness of the Judicial System • • • • Beyond privacy, the Court has also used substantive due process for the issues of excessive monetary damages awarded by juries and for problems associated with judicial conflicts of interest. Can jury awards for litigants who have been unlawfully harmed become so large as to constitute an unreasonable denial of essential fairness and a deprivation of property without due process of law? In BMW v. Gore (1996) the purchaser of a new automobile found out that the car he bought as new had been slightly damaged and repainted during transport to the dealership. BMW policy allowed new cars with very minor damage to be fixed and sold as new without disclosure to the dealer or purchaser. The purchaser sued and was awarded $4,000 in compensatory damages and $4 million in punitive damages. The state supreme court reduced it to $2 million and the U.S. Supreme Court said 5-4 that even that was “grossly excessive.” The Court has reduced jury awards in subsequent cases. In Caperton v. A.T. Massey Coal Co. the justices considered whether judges who are elected could be so beholden to the interests of campaign contributors that they may not be able to fair to litigants when a conflict of interest may be present. The Court ruled 5-4 that the Due Process clause of the 14th Amendment requires a judge to recuse himself not only when actual bias has been demonstrated or when the judge has an economic interest in the outcome of the case, but also when "extreme facts" create a "probability of bias." Conclusion • The Court has on occasion relied on the due process clause to protect rights not explicitly mentioned in the Constitution—both rights favored by conservatives (liberty of contract) and rights favored by liberals (privacy, abortion). • Critics suggest that substantive due process allows judges to act as legislators – to decide on their own what laws are so unreasonable as to violate due process. • They suggest that the people should make those decisions rather than unelected, unaccountable Supreme Court justices. • Are they right?