ARC000321 Lecture 13 Colonial Australia

advertisement

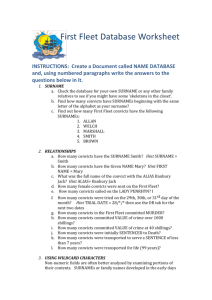

Colonial Australia A Direct North General View of Sydney Cove by Thomas Watling, 1794 Terra Australis Incognita (unknown southern land) The first recorded ship to chart the Australian coast and meet with Aboriginal people was the Duyfken (Little Dove) in 1606. Captained by Willem Janszoon and built in the Netherlands in 1595 the ship was just 20 metres from stem to stern, and 6 metres across the beam, with a draught (the depth of water it needed to float in) of only 2.45 metres. Duyfken (Little Dove) replica Abel Tasman - 1642 voyage VOC Captain Abel Tasman charted parts of the north, west, and southern coasts of Australia which was then known as New Holland. New Holland James Cook In 1770 the Royal Navy Lieutenant James Cook charted the Australian east coast in his ship HM Barque Endeavour Cook claimed the east coast for King George III of England on 22nd August 1770, at Possession Island. This new territory was named 'New South Wales‘ Captain Cook Memorial Museum, Whitby The ‘First Fleet’ 1788 Captain Arthur Phillip New South Wales The First Fleet, comprising 11 ships and around 1,350 people, arrived at Botany Bay between 18th and 20th January 1788. The area was deemed to be unsuitable for settlement and they moved north to Port Jackson on 26th January 1788 Matthew Flinders The process of British colonisation of Western Australia began in 1791 when George Vancouver claimed the Albany region in the name of King George III. Matthew Flinders was the first person to circumnavigate the continent 1801-1803 He named it Terra Australis or 'Australia’ The name Australia was adopted for the continent in 1817 Modern Australia Archaeology in Australia • Prehistoric Archaeology (the archaeology of Aboriginal peoples from c. 50,000 before present to AD 1788) • Historical Archaeology (the archaeology of Australia after permanent European Settlement in 1788) • Maritime Archaeology • In practice these categories often overlap within Cultural Heritage Management, which encompasses Aboriginal, Historical and Maritime sites http://www.asha.org.au/ The Australian Society for Historical Archaeology was founded in 1970 to promote the study of historical archaeology in Australia. In 1991 the Society was extended to include New Zealand and the Asia-Pacific region generally, and its name was changed to the Australasian Society for Historical Archaeology 1970s Historical Archaeology Early European settlements • Port Essington – Northern Territory • Corinella – Victoria Homesteads • Elizabeth farm - NSW • Old Saumarez Station – NSW Industrial sites • James King’s pottery – NSW • Fossil beach cement work – Victoria Aboriginal sites • Whybalenna, Tasmania The Archaeology of Convicts 161,000 convicts transported between 1788- 1867 Up until 1840 most buildings, roads, bridges built by convicts By the mid-1830s only around 6 per cent of the convict population were 'locked up‘ The majority of convicts worked on projects for free settlers and the authorities around the nation Archaeology of convict-built structures Sydney The First Government House, Sydney Rural New South Wales Great North Road Tasmania Port Arthur The First Government House, Sydney, 1789-1846 On 4th June 1789, just sixteen months after the first landing at Sydney Cove, the early settlers gathered to celebrate the birthday of King George III and the grand opening of Government House The building was designed and built by the convict brick-maker James Bloodsworth. The use of brick was initially limited because of the shortage of lime, a key ingredient in making mortar. Archaeologists have discovered that the lime used in the first Government House was made from oyster shells. Government House was used for 57 years before the old building was demolished The Great North Road The Great North Road was built by convict labour , often working in irons, between 1826 and 1836 to connect Sydney with Newcastle and the Upper Hunter Valley in NSW Much of this engineering master piece still exists and in parts still carries traffic Great North Road Grace Karskens University of New South Wales, Sydney By juxtaposing the location of different styles of surviving stonework with the known distribution of Road Gangs between 1827 and 1832, she found that a pattern of association between certain gangs and particular styles emerged. The Gangs appear to have been organised according to skills and the difficulty of terrain Port Arthur Port Arthur’s Separate Prison was closely modelled on Pentonville and was known as the Model Prison. It was built in 1849–50 with three wings of cells and a fourth wing containing a chapel Female Factories • 20 per cent of the first convicts were women • Women were typically sentenced for periods of 7 or 14 years, usually for petty theft from their employers in England • The ‘female factories’ were originally profit-making textile factories Ross Female Factory, Tasmania Female convicts were transported to Tasmania (then called Van Diemen's Land) from 1803, when the colony was founded, to 1853 The Ross Female Factory operated towards the end of the transportation period from March 1848 until November 1854. It served as a factory as well as hiring depot, an overnight station for female convicts travelling between settlements, a lying-in hospital and a nursery. Ross Female Factory, Tasmania Eleanor Casella University of Manchester Solitary cells Ross Female Factory, Tasmania Networks of underground exchange subverted the controlled institutional landscape Highest frequency and density of illicit artefacts (tobacco and alcohol related) and buttons (for exchange) found in Solitary Cells “While under solitary sentence, the factory ‘incorrigibles’ continued to maintain their access to forbidden indulgences, relieving the monotonous boredom, cold, and hunger of disciplinary confinement with a pipe and a bottle…” Eleanor Casella Landscapes of Punishment and Resistance p. 117 Gold mining from 1851 Dolly’s Creek, Victoria Dolly’s Creek: A Goldfield Community in Victoria Susan Lawrence La Trobe University Melbourne Excavation of a miners frame tent encampment occupied from late-1850s to 1890s “homes where women seem to have lived had most elaborate assemblages…transfer-patterned tablewares…glass cake stands…floral wall paper…pipe-clay whitened chimneys with mantel piece and brass clock” Suggests that everyone – male and female - preferred to eat and drink from ceramic plates and cups, but the tents with women seemed more intent on pursuing the 19th century ideology of respectability A gold miner’s tent The clock house The chimney house The Rocks, Sydney The Rocks, Sydney (Grace Karskens, again) Convicts and ex-convicts attempted to refine their behaviour and eating habits The 700 wooden bowls and platters sent with the First Fleet were quickly replaced with decorative ceramics Not much elaborate tableware prior to 1810, but after that date gravy boats, milk jugs, sugar bowls and other fancy settings introduced Drinking however belonged to an older realm of behaviour and the habit of passing a bottle or decanter around or drinking from a shared ‘circling glass’ (?an Irish habit) persisted into the 19th century Lake Innes: Port Macquarie NSW ‘Privilege and servitude’ revealed in archaeological residues. Lake Innes Estate flourished in the 1830s, declined during the 1840s. In its heyday viability was based on the labour of transported convicts, but paid free workers were also employed. A complex social hierarchy, at the top of which were the residents of Lake Innes House: family members and friends of Major Archibald Clunes Innes, a retired British army officer who created a colonial version of the landed estate that fate had denied him in his native Scotland Material Culture and Consumer Society: Dependent Colonies in Colonial Australia Mark Staniforth, Flinders University, Adelaide Research on shipwrecks from the Matthew James (1841) in 1974 to the Sydney Cove (1797) in 1994 led Staniforth to conclude that British imported goods were vital to the successful colonization of Australia for more than purely economic reasons: • to distinguish the colonists from indigenous groups • to reassure the colonists about their place in the world • to help establish the colonists’ own networks of social relations Challenging the ‘Great Australian Silence’ The phrase ‘Great Australian Silence’ was coined by W.E.H. Stanner an anthropologist in 1968 19th century conceptions of Aboriginal society portrayed it as static and primitive; the bottom rung of the ladder of civilization with Europeans at the top This view was perpetuated by archaeology and anthropology, which searched for the ‘primitive’ and used structural-functionalist models to give a static impression of Aboriginal culture Even well-meaning attempts to preserve ‘disappearing’ Aboriginal cultures served to imply they were the primitive ‘deep foundations’ of the new nation Governor Davey's [sic] . Proclamation to the Aborigines, 1816 Painting - oil painting on pine board Incorrectly labelled as "Governor Davey's Proclamation to the Aborigines" Actually Lieutenant-Governor George Arthur's proclamation of c.1828-1830 Attempted Genocide Aboriginal Resistance Truganini was a negotiator and spokesperson for her people. Her mother had been killed by whalers, her uncle had been shot by a soldier and three of her sisters had been abducted and sold to sealers. Her betrothed, Paraweena, was drowned in the Channel by timber sawyers. In 1838, Truganini was part of a guerilla war campaign at Port Philip, Victoria with a group of other Tasmanian Aborigines. The men were executed in Melbourne's first public execution. Truganini returned to Wybaleena in 1842. Truganini 1812-1876 Truganini died in 1876. Her skeleton was displayed at the Tasmanian Museum until 1947. In 1976 her remains were cremated and scattered according to her wishes. Samples of her skin and hair were finally returned from the British College of Surgeons in 2002. A shell necklace attributed to Truganini was found in a southern England museum in 2001. Rodney Harrison & Christine Williamson The first book length historical archaeology of Aboriginal Australia and its application in researching the shared history of Aboriginal and settler Australians. Kimberley Points Traditionally, Kimberley points were made from a variety of fine-grained stone and ranged from approximately 1 - 8 cm in length. Aboriginal toolmakers found that glass and ceramic, including ceramic telegraph line insulators, were very well suited to the production of Kimberley points Increased demand - from both Aboriginal exchange networks and an emergent 'tourist' trade with non-Aboriginal people led to the refinement of techniques and their size. Finished glass points up to 20 cm long have been found. Landscape studies From the late 1980s – Aboriginal-European interaction has been explored in “frontier” zones Participation on the cattle industry offered Aboriginal people a means to remain in traditional country in co-existence with settlers, and maintaining their kin relations Large scale landscape level studies attempted by prehistorians; in Arnhem land, northern Australia, Aboriginal people gravitated toward European populations centres and became sedentary Other studies have explored how access to traditional sites was cut off following colonization, or changed in sites that lay “beyond the imperial net” New studies In south east Australia most Aboriginals confined to reserves from the 1860s. Daily life and experience from that time can be found and studied in these places, challenging the accounts of missionaries, etc Where archaeological representations once stressed the pastness and stasis Aboriginal culture, they now foreground regional and temporal variation within Aboriginal culture over the past 60,000 years, historicizing our understandings of Aboriginality Aboriginal archaeology Tim Murray, La Trobe, Melbourne The Archaeology of Contact in Settler Societies CUP 2004 There is a need to reconcile shared histories with radically different conceptions of time and culture, and to acknowledge the European arrival as an invasion – not a neutral colonization of an empty land This can be difficult; some Aboriginal peoples have adopted a “strategy of refusal” rejecting European claims to speak on their behalf and efforts to construct consensual narratives of the nation