Medieval Feudalism

advertisement

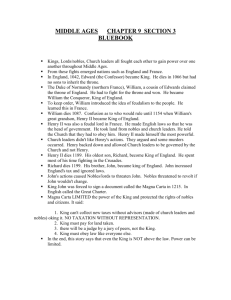

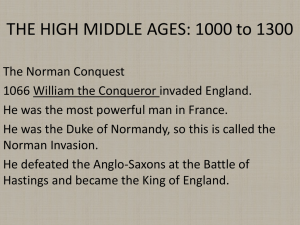

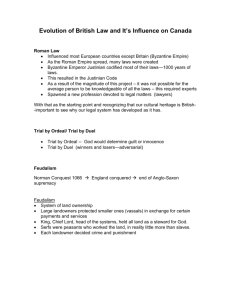

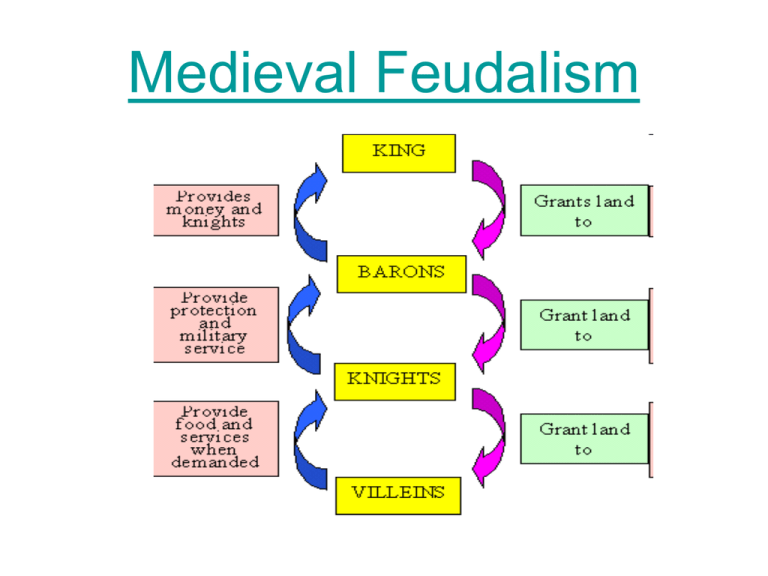

Medieval Feudalism “But what is the office of the duly ordained soldiery? To defend the church, to assail infidelity, to venerate the priesthood, to protect the poor from injuries, to pacify the province, to pour out their blood for their brothers (as the formula of their oath instructs them), and, if need be, to lay down their lives” John Of Salisbury What Do We Mean By ‘Medieval’? • • • • • • Medieval refers to a time period usually thought to begin around the time of the first crusade 1096 and end when the Italian Renaissance began. Medieval also refers to a distinct world view, in philosophy, in the arts, in literature and in language. Medieval society began as a simple (and crude) arrangement between King, Knight, churchman and peasant. It went on to develop into the Europe of Chaucer and Dante, of great cathedrals and universities, of the English monarchy and Parliament, of Canon, Civil and English law and it saw the blossoming and expansion of London. The aim of the greatest minds was to provide man with strong institutions and strong beliefs in a world that was turbulent and unpredictable. Easier said than done, but there is no doubt that society progressed during these 400 years or so. In England this progression began with the imposition of feudalism on society (although, in truth it had already begun) Feudalism • • • • • • • Medieval Europe was not held together as a single state. The political structure was feudalism Simply explained, feudalism was a system of the exchange of property for personal service. The person who granted the property was the ‘lord’ or ‘over-lord’ The person who received it was the vassal. This vassal promised service to his lord in a ceremony called the ‘act of homage’ All land belonged to the king, he granted it to barons (his vassals) in exchange for fees, taxes and the service of his knights – who would get their own parcels of land for their service, they in turn would grant it to their vassals. Here the allocation would stop. In the absence of money and products, land was the foundation on which all trade and exchange was based. (land, after all, is the most basic asset a nation can possess) The Domesday Book • • • • • • By 1086 William wanted to know who in England owned which land, and how much it was worth. He needed this information so that he could plan his economy, find out how much was produced and discover how much tax he could get. He sent a team of people throughout his land to discover such information. This survey was the only one of its kind in Europe. Unpopular with the people, because they felt they could not escape from its findings. It reminded them of the paintings of the Day of Judgment, or ‘doom’ they saw on the walls of their churches, hence the book was christened the ‘Domesday Book’ After William I (1087-1154) • • • • • • • • William died in 1187 He was followed to the throne by his first son William II (1187-1100) and then by his second son Henry I (1100-1135). Both continued to strengthen the king’s power. Henry established the Exchequer to deal with the collection of revenue. On Henry's death, his daughter was supposed to succeed him, however her cousin, Stephen, had other ideas and claimed the crown becoming Stephen I. So raged a civil war which Matilda very nearly won, but by 1148 she had had enough and fled to France. Henry reigned until 1154. However, Matilda had the last (posthumous) laugh as her son, also Henry (II) ascended the throne . Norman rule had come to an end (but not its influence) and was replaced by The Royal House of Plantagenet (Anjou) The Legal System Reformed • • • • • Henry II (1154-1189), the most powerful European monarch of his day Main contribution was development of the legal system He established common English law, created a bench of judges, precedent law and trial by jury (as opposed to ‘trial by battle’, ‘trial by water’ and ‘trial by hot iron’) This common law still distinguishes English-speaking countries with those where law is of Latin and Roman origin. In reality not English law, rather Norman law as those who wrote/devised it were French speakers. Conflict Of Church And State • • • • • • • • Unfortunately, for Henry, he is best remembered for the murder of Thomas Beckett, Archbishop of Canterbury This tragedy had its roots in the Church's ‘Benefit of Clergy’ In short this gave the church the power to try churchmen of crimes regardless of the law they had broken (i.e. church and common law). It also gave them the power to try the laity for contravening church law. Henry did not like this and thus appointed his friend Thomas Beckett to the highest religious position in the land, Archbishop of Canterbury. However, Thomas went ‘all religious’ on him and refused to do anything about the ‘privilege of the clergy’ Henry was furious and Beckett fled to France. When he returned he was killed by Henry’s knights (mistakenly as Henry claimed) Richard And John I • • • • • • • • • • • Richard succeeded his father to the throne in 1189 He spent only 6 months of his 10 year reign in England The other 9 ½ years were spent fighting. Richard lived to fight and earned the name Richard the Lionheart because of his bravery (some would say his stupidity) He took part in the disastrous third crusade and ended up having to tax his nobles to pay for his adventures. He was also captured in Germany when returning from the same crusade and the people of England had to pay his ransom. He was killed, appropriately enough, by an arrow while engaging in his favourite pastime, fighting. On his death, he left England near bankruptcy and his brother John I (1199-1216) was expected to clean up the mess. John taxed the nobles and cut back on expenses (e.g. sent judges to the countryside less often and so on) to try and do something about England's financial mess. The nobles had had enough of being taxed and civil war loomed. However, war was averted with the signing of the Magna Carta The Magna Carta 1215 (part 1) • 15 June 1215 at Runnymede. “No free man shall be seized or imprisoned or stripped of his goods or possessions save by lawful judgment of his peers or equals or by law of the land” “..to no one shall I sell or deny or delay justice” • • Today such sentiments are seen as basic human rights (and they echo the Declaration of Human rights) but for the time they were earth shattering. Admittedly such rights were far down the document, what was much more prominent were the points ensuring the protection of the Church and the barons (the authors of the document.) The Magna Carta 1215 (part 2) • • • • • John signed the Magana Carta reluctantly. Then proceeded to appeal to Pope Innocent to have it annulled, which he duly did. John then declared the document null and void. War broke out John then went and died (1216) However despite this turn of events this document and its restrictions on royal power marked the beginning of constitutional government. Henry III (1216-1272) • • • • • Like his father he also ignored the Magna Carta Difficult as it may seem he alienated the barons further by taxing them more and, on top of this he started distributing English land to French Nobles. The Barons rebelled under the leadership of Simon De Montfort and ultimately captured and imprisoned the King. Simon De Montfort thus became the supreme authority in England for fifteen months. Under his authority constitutional government continued to develop The Birth of Parliament • • • • • • • Under De Montfort, the Great Council of Barons who advised the king, came to be called ‘Parliament’ In 1265 parliament accepted two representatives from each chartered town in England. The barons, as usual, were unhappy about this, they released the still imprisoned king and Simon de Montfort was killed by the king’s forces. De Montfort’s supporters continued to fight and eventually a compromise was reached with Henry III The crux of this agreement was that from then on Parliament would contain both townspeople and nobility. This developed further when at the beginning of the fourteenth century, parliament was split into two houses - an upper house for the nobility ‘The Lords’, and a lower house for the townspeople, ‘The Commons’ By the end of the thirteenth century, parliament had already become a cornerstone of government. The Rise Of The Towns • • • • • • In the thirteenth century towns became increasingly important. Why? The crusades had opened up new trade routes which meant that trade centers such as London expanded. Townspeople got rich and as a result formed merchants guilds and trade guilds. These became relatively powerful and their members became involved in local government. It was only a matter if time before they demanded representation in national government. The ownership of land was no longer the only source of wealth. This development undermined the power of the barons. This rapid growth of towns resulted in a major problem that was to have an impact on English society. People lived in close proximity to each other, there was no sanitation, malnutrition was rife. This was a breeding ground for infectious diseases and it left the door open for the ‘Daddy of all Diseases’…..The Black Death.