Nutrition and pancreatic cancer Presentation by Sinead

advertisement

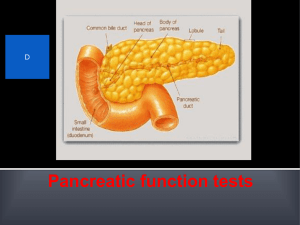

The Adelaide & Meath Hospital Incorporating the National Children’s Hospital Trinity College Dublin Nutrition & Pancreatic cancer Dealing with exocrine insufficiency and options for feeding AUGIS 15th Annual Scientific Meeting, Belfast 2011 Sinead Duggan siduggan@tcd.ie Centre for Pancreatico-Biliary Diseases & Trinity Centre for Health Sciences, AMNCH, Dublin Financial support: Health Research Board Ireland Presentation outline Cachexia and severe malnutrition in pancreatic cancer Dealing with exocrine dysfunction in pancreatic cancer 1. Cachexia and severe malnutrition in pancreatic cancer Nutritional problems in pancreatic cancer • • • • • • • • • • • Pain Constipation Obstruction Indigestion Malabsorption Diabetes Post-surgery Anorexia Tissue Wasting Weight Loss Loss of compensatory increase in feeding Cancer AnorexiaCachexia Syndrome Cachexia: From Greek kakos (“bad”) hexis (“condition”) Cachexia process is multifactorial and incompletely understood Uomo et al. JOP. J Pancreas (Online) 2006; 7(2):157-162. Differs from simple starvation Incidence of Cancer Cachexia (Tinsdale 1999, Gibney 2005) 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% rea c n Pa s Ga ck tal us e c g /N ha Re d / p a o l so He Co Oe ic str ng Lu o Pr te st a B s rea t Weight loss in cancer: Does it matter? The physical effects Quality of life Fitzsimmons et al (1999). Development of a disease specific quality if life module to supplement the EORTC core QOL questionnaire, the QLC-C30 in patients with pancreatic cancer, European Journal of Cancer Care. 95:6 Cachexia worsens prognosis Pancreatic cancer: Resectable disease Nutritional intervention in cancer Pre-cachexia Weight loss < 10% Nutritional intervention works Does it work? Cachexia Weight loss > 10% Conventional nutritional intervention may not work Nutritional intervention Patients with gastric / colorectal cancer Mean weight loss of 7.2% & 5.5% at baseline Individual support vs. standard care Statistically significant at 12 and 24 months Nutritional intervention Weight QOL SGA Head and Neck Cancer (n=60) Regular, intensive dietetic counselling by dietitian + ONS or usual care (Nutrition booklet, no individualisation) 2.6% & 3.6% weight loss at baseline Management of cancer cachexia Nutrition ineffective? • 2 large randomised controlled trials of ONS in cachectic cancer patients concluded that weight/ body composition, QOL, survival, response rate fail to improve despite increases in nutrient intake • “The metabolic alterations that occur in these patients seem to prevent the effective use of additional calories supplied, resulting in ongoing wasting” • Options? – Megace, corticosteroids, β2-adrenoceptor agonists, thalidomide, melatonin, growth hormone, insulin, NSAIDs – Eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) Barber MD. The pathophysiology and treatment of cancer cachexia. Nutrition in clinical practice (2000) 17:203-209 Megace Megestrol acetate for treatment of anorexia-cachexia syndrome Berenstein G, Ortiz Z. (Cochrane Review) + • Used to improve Megace better than placebo for appetite and weight gain appetite and gain weight in cancer-related cachexia • Mechanism unknown • 32 trials reviewed • >5,000 patients No dosing guidelines Weight gain adipose tissue No conclusion of Quality of life, functional ability EPA • Role in membrane, receptor, enzyme function • Precursors for prostanoid synthesis • Helps to down-regulate the inflammatory response associated with cancer-induced weight loss • Focus of many recent trials EPA studies N=24 Advanced Pancreatic Ca Weight losing (mean 19-21%) No significant changes in weight / LBM Energy expenditure and Physical activity significantly increased in EPA group (but not in control) EPA N=200 Pancreatic Ca; weight losing ~19-20% Randomised to 2 cans per day of control or EPA; 8 weeks Both groups demonstrated halting weight loss/gain of Lean Body Mass Compliance issues mean intake 1.4 cans • Post-hoc analyses: – Significant correlation between EPA intake and weight gain / lean body mass gain – Control group: no such correlation Only patients who took recommended 1.5-2 cans EPA supplement per day gained weight / LBM Quality of Life: Intake of EPA supplement correlated positively with QOL Ryan et al, Annals of Surgery, vol 249, 2009 • PRCT: Examine effect of peri-operative EPA enriched EN vs standard • Inclusion: Adults with resectable oesophageal cancer • 2.2g/ day of EPA vs nil (control) • Both groups fed 55 Results: Body Composition Analysis 56 31 * 55 54 * 30 2952 52 51 50 Standard 9 * 8.5 8 7.5 7 EPA Standard 50 26 25 Pre op Day -5 POD 21 *P<0.05 Pre op Day 28 -5 POD 21 51 27 53 EPA Leg Muscle Mass 53 Trunk Fat Free Mass (Kg) Whole Body Fat Free Mass (Kg) 54 ProSure EPA Control Standard Lean Body Composition Changes EPA Enriched 0 kg +0.2 kg Standard EN EPA resulted in anabolism / maintenance of muscle mass in patients with oesophageal cancer 0 kg 8% 0.2 kg (p=0.01) 1.4 kg (p=0.03) 0.3 kg (p=0.05) “severe” wt loss 39% Patient presenting with cancer Nutritional Goals - Preserve LBM - Functional ability - Physical activity - Quality of life Weight loss: less than 10% Pre-Cachexia Weight loss: more than 10% Cachexia Nutrition Options ? Intensive nutrition input +ONS Regular follow-up Specialised nutrition ?Megace etc EPA feed Standard Nutritional Intervention? 2. Dealing with exocrine dysfunction in pancreatic cancer Exocrine function • Normal fat digestion – Fat digestion begins in the mouth (very limited) and stomach (10-30% of all lipid breakdown1) – Most fat digestion by pancreatic lipase – Approx 20,000-50,000 units of lipase are needed to digest a typical meal • 2 key hormones – CCK – triggers the release of pancreatic enzymes from the pancreas – Secretin – stimulates bicarbonate secretion form the pancreas to ↑ pH (lipase inactivated in acidic environment) • With pancreatic damage- lingual and gastric lipases cannot compensate 100% for loss of pancreatic function 1. Layer P et al. Lipase supplementation therapy: standards, alternatives and perspectives. Pancreas. 2003;26(1):1-7 Impaired digestion in pancreatic cancer • Cancer in the head of the pancreas may obstruct the pancreatic duct, impairing secretion • Surgery (e.g. Whipple) changes the mechanical and secretary process • Damage to the intestinal mucosa (radiation therapy, surgery), may reduce CCK release • Motility disturbances may affect secretory and motor functions of the GI tract Signs and symptoms of malabsorption • Steatorrhoea (foul smelling, fatty stools) • Oily stools, undigested food in stools • Diarrhoea • • • • • Weight loss Bloating/ flatulence Abdominal pain/ cramping Dehydration Electrolyte disturbances Diagnosing malabsorption • Usually clinically evident – But malabsorption may exist even in the absence of overt steatorrhoea – Patients may reduce intake to counteract symptoms • Direct tests – Collecting pancreatic secretions via duodenal intubation • Indirect tests – Cheaper and easier to administer – Less sensitive and less specific – 4 categories Indirect tests Faecal test Breath tests Urinary tests Blood tests Indirect tests (Source: Australasian treatment guidelines for the management of PEI) Faecal tests Breath tests Urine tests Blood tests 3-day faecal fat test Triolein breath test Bentiromide Trypsinogen Steatocrit Fluoresceine Dilaurate Faecal Chymotrypsin Faecal Elastase-1 Sudan III stain Gold standard: 3-day fat -Ingested lipids test liberate CO2 -100g fat for 3-5 days following hydrolysis -Weigh food -Not fully validated -keep dietary records Do not differentiate -Stools collected over 72- between pancreatic 96 hours and non-pancreatic causes -Use non-absorbable substrates that are specifically cleaved by pancreatic enzymes -Urine collection over time period -Superseded by simpler blood tests -Trypsin exclusively synthesised by the pancreas and small amts released into blood as tripsinogen -Validated in CF % of exocrine insufficient subjects Method of testing exocrine insufficiency Matsumoto & Traverso , 2006 68% Kato et al , 1993 92 % Faecal elastase Secretin test Ihse et al , 1977 87% Duodenal tube, Lundh Study details (Thanks to Lorraine Watson, MSc. Project) Pancreatic cancer subjects only meal to measure lipase conc. Pancreatic cancer subjects & subjects other conditions Sato et al , 1998 Ohuchida, 2007 Ohtsuka et al, 2001 Pancreatic cancer subjects post resection only Kato et al, 1993 Pancreatic cancers & subjects with other conditions post resection Tran et al , 2008 Norback et al, 2007 Sato et al, 1998 Ohtsuka et al , 2001 46 % 66 % 26 % BT-PABA Chymotrypsin Chymotrypsin 80 % Secretin test 88% (76% severe) 100% (92% severe) 75 % Faecal elastase 50% Chymotrypsin Faecal elastase BT-PABA Faecal Elastase-1 • Widely used • Cheap, non-invasive, widely available • Pancreatic enzyme that is not degraded during digestion and may be measured in the stool • Not affected by enzyme use • Does not require timed stool collection • Does not require special diet Sensitivity limited in mild pancreatic insufficiency PERT • Pancreatic enzyme replacement therapy – the oral administration of manufactured digestive enzyme preparations for use in exocrine insufficiency No guidelines on specific doses, or specific patients types suitable PERT in palliative pancreatic cancer • RCT, double-blind, 21 patients with unresectable pancreatic cancer • 50,000 units Lipase with meals, 25,000 units with snacks for 8/52 • Both groups were counseled on dietary intake PERT in post pancreatic surgery patient • Matsumoto & Traverso, Journal of Gastrointestinal Surgery, 2006 • 182 patients over 4.3 years, proximal PD • Faecal-Elastase-1 measured in 138 patients – Pre-op (n=138), 3+1 mth (n=40), 12+2 mth (n=22), 24+3 mth (n=20) • Study conclusions – A third of patients pre-op will have exocrine insufficiency – Elastase levels further depressed in the majority post-op – After PD, PERT should be given to all patients with pancreatic cancer, especially those with impending adjuvant therapy Administering PERT Supplement: Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 2010 -Lipase irreversibly denatured by pH<4 -Enteric-coated preparations developed -Coating only dissolves when pH is >5.5 Dose and administration • Preparations are dosed by lipid content • Min dose of 25,000-50,000 per meal to reduce steatorrhoea to <15g/ day to compensate for pancreatic insufficiency1 • Dietary assessment vital – check diet regularly and move to protein supplementation early2 • Dose should be gradually increased until symptoms are controlled2 • Try a PPI or H2 blocker 1. Kelly & Layer. Human pancreatic exocrine response to nutrients in health and disease. Gut 2005; 54(Supp VI):vi1-28 2. Imrie et al, Expert commentary: how we do it. Aliment. Pharm and Ther 2010; 32 (suppl 1): 21-25 Side effects and interactions • Typically dose-related • Common side-effects – Nausea, vomiting, constipation, diarrhoea, abdominal distension • Uncommon side effects May result from underlying disease – Skin reactions • Mouth and perianal irritation, intestinal allergic reaction • Fibrosing colonopathy – Methacrylic Acid Copolymer Larger doses in small infants Older preparations Current suggested practice Imrie et al, 2010: based on Layer & Keller, 2003 ‘At every step in the algorithm, dietary intake should be completely reassessed, and diet and pancreatic enzyme dose altered if necessary’ Dietary assessment • Type of food eaten (fat content) • • • • Meals, snacks, liquids, supplements Method of cooking Volume of food at each meal Timing, frequency of meals • When enzymes are being taken • How much taken at each time • How are enzymes taken (crushed, sprinkled, whole) • • • • • PPI/ H2 Blockers Symptoms post-prandially; malabsorption, constipation Weight, weight history, muscle mass Monitoring of micronutrients, particularly fat soluble vitamins Requirement for supplementation: ONS, micronutrients, MCT-fat Individualised patient education vital so they can alter enzymes with changing circumstances Patient information booklet on the use of pancreatic enzymes Produced by the Nutrition Interest Group of the Pancreatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, in conjunction with Abbott Nutrition The pancreatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland • Both a Dietitian group (NIG) and a Clinical Nurse Specialist group within this society • 4th Annual Nutrition Symposium runs in conjunction with the main annual meeting • Dublin 1-2nd December • Focus on nutrition in acute pancreatitis, chronic pancreatitis and pancreatic cancer • www.pancsoc.org.uk Thank you siduggan@tcd.ie Acknowledgments Dr Aoife Ryan – SJH Lorraine Watson