poster 8 - Clinical Skills Managed Educational Network

advertisement

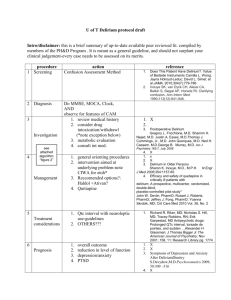

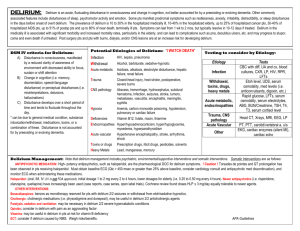

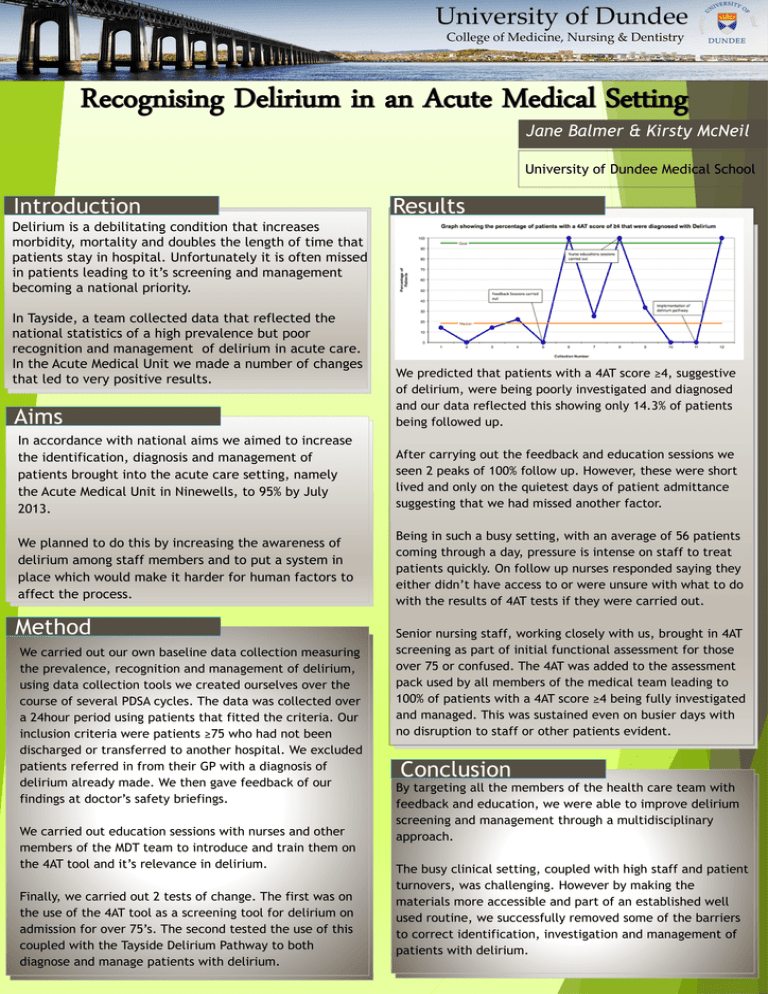

. University of Dundee College of Medicine, Nursing & Dentistry Recognising Delirium in an Acute Medical Setting Jane Balmer & Kirsty McNeil University of Dundee Medical School Introduction Results Delirium is a debilitating condition that increases morbidity, mortality and doubles the length of time that patients stay in hospital. Unfortunately it is often missed in patients leading to it’s screening and management becoming a national priority. In Tayside, a team collected data that reflected the national statistics of a high prevalence but poor recognition and management of delirium in acute care. In the Acute Medical Unit we made a number of changes that led to very positive results. Aims We predicted that patients with a 4AT score ≥4, suggestive of delirium, were being poorly investigated and diagnosed and our data reflected this showing only 14.3% of patients being followed up. In accordance with national aims we aimed to increase the identification, diagnosis and management of patients brought into the acute care setting, namely the Acute Medical Unit in Ninewells, to 95% by July 2013. After carrying out the feedback and education sessions we seen 2 peaks of 100% follow up. However, these were short lived and only on the quietest days of patient admittance suggesting that we had missed another factor. We planned to do this by increasing the awareness of delirium among staff members and to put a system in place which would make it harder for human factors to affect the process. Being in such a busy setting, with an average of 56 patients coming through a day, pressure is intense on staff to treat patients quickly. On follow up nurses responded saying they either didn’t have access to or were unsure with what to do with the results of 4AT tests if they were carried out. Method We carried out our own baseline data collection measuring the prevalence, recognition and management of delirium, using data collection tools we created ourselves over the course of several PDSA cycles. The data was collected over a 24hour period using patients that fitted the criteria. Our inclusion criteria were patients ≥75 who had not been discharged or transferred to another hospital. We excluded patients referred in from their GP with a diagnosis of delirium already made. We then gave feedback of our findings at doctor’s safety briefings. We carried out education sessions with nurses and other members of the MDT team to introduce and train them on the 4AT tool and it’s relevance in delirium. Finally, we carried out 2 tests of change. The first was on the use of the 4AT tool as a screening tool for delirium on admission for over 75’s. The second tested the use of this coupled with the Tayside Delirium Pathway to both diagnose and manage patients with delirium. Senior nursing staff, working closely with us, brought in 4AT screening as part of initial functional assessment for those over 75 or confused. The 4AT was added to the assessment pack used by all members of the medical team leading to 100% of patients with a 4AT score ≥4 being fully investigated and managed. This was sustained even on busier days with no disruption to staff or other patients evident. Conclusion By targeting all the members of the health care team with feedback and education, we were able to improve delirium screening and management through a multidisciplinary approach. The busy clinical setting, coupled with high staff and patient turnovers, was challenging. However by making the materials more accessible and part of an established well used routine, we successfully removed some of the barriers to correct identification, investigation and management of patients with delirium.