HESPERÍA - ResearchGate

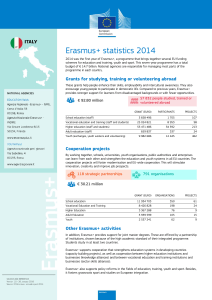

advertisement

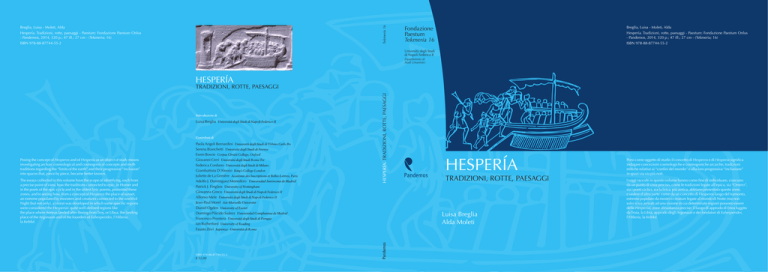

Tekmeria 16 Breglia, Luisa - Moleti, Alda Hespería. Tradizioni, rotte, paesaggi - Paestum: Fondazione Paestum Onlus - Pandemos, 2014, 320 p.; 47 ill.; 27 cm - (Tekmeria; 16) ISBN 978-88-87744-55-2 Fondazione Paestum Tekmeria 16 Breglia, Luisa - Moleti, Alda Hespería. Tradizioni, rotte, paesaggi - Paestum: Fondazione Paestum Onlus - Pandemos, 2014, 320 p.; 47 ill.; 27 cm - (Tekmeria; 16) ISBN 978-88-87744-55-2 Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici HESPERÍA Introduzione di Luisa Breglia Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II Contributi di Posing the concept of Hesperos and of Hesperia as an object of study means investigating archaic cosmological and cosmogonical concepts and myth traditions regarding the “limits of the earth” and their progressive “inclusion” into spaces that, piece by piece, became better known. The essays collected in this volume have the scope of identifying, each from a precise point of view, how the traditions connected to epic, in Homer and in the poets of the epic cycle and in the oldest lyric poems, presented these zones, and to seeing how, from a concept of Hesperos the place of sunset, an extreme populated by monsters and creatures connected to the world of were considered the Hesperiai place of the Argonauts and of the founders of Euhesperides, l’Hiberia, la Keltiké. Paola Angeli Bernardini Università degli Studi di Urbino Carlo Bo Serena Bianchetti Università degli Studi di Firenze Ewen Bowie Corpus Christi College, Oxford Giovanni Cerri Università degli Studi Roma Tre Federica Cordano Università degli Studi di Milano Giambattista D’Alessio King’s College London Juliette de La Genière Académie des Inscriptions et Belles-Lettres, Paris Adolfo J. Domínguez Monedero Universidad Autónoma de Madrid Patrick J. Finglass University of Nottingham Giovanna Greco Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II Alfonso Mele Università degli Studi di Napoli Federico II Jean-Paul Morel Aix-Marseille Université Daniel Ogden University of Exeter Domingo Plácido Suárez Universidad Complutense de Madrid Francesco Prontera Università degli Studi di Perugia Ian Rutherford University of Reading Fausto Zevi Sapienza - Università di Roma ISBN 978-88-87744-55-2 ¤ 52,00 HESPERÍA. TRADIZIONI, ROTTE, PAESAGGI TRADIZIONI, ROTTE, PAESAGGI HESPERÍA TRADIZIONI, ROTTE, PAESAGGI Luisa Breglia Alda Moleti Porsi come oggetto di studio il concetto di Hesperos e di Hespería indagare concezioni cosmologiche e cosmogoniche arcaiche, tradizioni in spazi via via più noti. da un punto di vista preciso, come le tradizioni legate all’epica, sia “Omero”, sia i poeti ciclici, sia la lirica più antica, abbiano presentato queste zone, e vedere d’altra parte come da un concetto di Hesperos luogo del tramonto, estremo popolato da mostri o creature legate al mondo di Notte (ma non solo) si sia arrivati ad una visione in cui determinate regioni possono essere delle Hesperíai, zone abbastanza precise: il luogo di approdo di Enea fuggito da Troia, la Libia, approdo degli Argonauti e dei fondatori di Euhesperides, l’Hiberia, la Keltiké. Tekmeria 16 Tekmeria 16 Direttore della collana Emanuele Greco Redazione Fausto Longo, Ottavia Voza Grafica Pandemos S.r.l. Impaginazione Alda Moleti Il volume è stato pubblicato con fondi PRIN2009, prof. Luisa Breglia, Università degli Studi di Napoli ‘Federico II.’ I volumi della collana Tekmeria sono sottoposti alla valutazione del Consiglio Scientifico della Fondazione Paestum e, successivamente, al processo di peer review effettuato da valutatori specialisti anonimi. I nomi dei revisori, con la relativa documentazione, sono conservati presso gli archivi della casa editrice Pandemos. All the volumes of the Tekmeria Series are evaluated by the Scientific Advisory Committee of the Paestum Foundation and are peer-reviewed by external anonymous reviewers. The names of these reviewers and their evaluations are kept within the archives of the publishing company Pandemos. In copertina: Un calco del particolare della Tabula Iliaca Capitolina, Roma - Musei Capitolini (inv. MC 0316), recante Enea, in compagnia di Miseno, Anchise ed Ascanio, in procinto di partire per l’Hespería. In quarta di copertina: Un particolare della Tabula Iliaca Capitolina, Roma - Musei Capitolini (inv. MC 0316), raffigurante Enea insieme a Miseno, Anchise ed Ascanio, in procinto di partire per l’Hespería (si ringraziono i Musei Capitolini per aver concesso la riproduzione) Luisa Breglia, Alda Moleti (a cura di), Hespería. Tradizioni, rotte, paesaggi ISBN 978-88-87744-55-2 © Copyright 2014 Pandemos S.r.l. Proprietà letteraria riservata Fondazione Paestum Centro di Studi Comparati sui Movimenti Coloniali nel Mediterraneo - Onlus www.fondazionepaestum.it - info@fondazionepaestum.it Distribuzione Pandemos S.r.l. via Magna Grecia - casella postale 62 - 84047 Paestum (Sa) Tel./Fax 0828.721.169 www.pandemos.it - info@pandemos.it Fondazione Paestum Tekmeria 16 Università degli Studi di Napoli “Federico II” Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici HESPERÍA TRADIZIONI, ROTTE, PAESAGGI Luisa Breglia Alda Moleti Paestum 2014 Volumi della collana 1. E. Greco, F. Longo (a cura di) Paestum. Scavi, Studi, Ricerche. Bilancio di un decennio (1988-1998) Paestum 2000 2. E. Greco (a cura di) Architettura, Urbanistica, Società nel mondo antico Giornata di studi in ricordo di Roland Martin Paestum 2001 3. E. Greco (a cura di) Gli Achei e l’identità etnica degli Achei d’Occidente Atti del Convegno Internazionale Paestum - Atene 2002 4. R. De Gennaro, A. Santoriello Dinamiche insediative nel territorio di Volcei Paestum 2003 5. R. De Gennaro I circuiti murari della Lucania antica (IV-III sec. a.C.) Paestum 2004 6. E. Greco, E. Papi (a cura di) Hephaestia 2000-2006 Atti del Seminario Paestum - Atene 2008 7. O. Voza (a cura di) Parco Archeologico di Paestum. Studio di fattibilità Paestum 2009 8.1. M. Cipriani, A. Pontrandolfo (a cura di) Le mura. Il tratto da Porta Sirena a Torre 28. Paestum. Scavi, Ricerche, Restauri Paestum c.d.s. 8.2. M. Cipriani, A. Pontrandolfo (a cura di) Le mura. Il tratto nord-orientale. Paestum. Scavi, Ricerche, Restauri Paestum c.d.s. 8.3. M. Cipriani (a cura di) L’agora e l’insula IS 2-4. Paestum. Scavi, Ricerche, Restauri Paestum c.d.s. 8.4. G. Avagliano (a cura di) Il restauro degli isolati a ovest del santuario meridionale. Paestum. Scavi, Ricerche, Restauri Paestum c.d.s. 9. R. Bonaudo, L. Cerchiai, C. Pellegrino (a cura di) Tra Etruria, Lazio e Magna Grecia: indagini sulle necropoli Atti dell’Incontro di Studio Paestum 2009 10. N. Laneri Biografia di un vaso Paestum 2009 11. F. Camia, S. Privitera (a cura di) Obeloi. Contatti, scambi e valori nel Mediterraneo antico. Studi offerti a Nicola Parise Paestum 2009 12. A. Polosa Museo Archeologico Nazionale della Sibaritide. Il Medagliere Paestum 2009 13. F. Longo Le mura di Paestum. Antologia di testi, dipinti, stampe grafiche e fotografiche dal Cinquecento agli anni Trenta del Novecento Paestum 2012 14. S. Marino Copia / Thurii. Aspetti topografici e urbanistici di una città romana della Magna Grecia Paestum - Atene 2010 15. G. Aversa I tetti achei. Terrecotte architettoniche di età arcaica in Magna Grecia Paestum 2012 16. L. Breglia, A. Moleti (a cura di) Hespería. Tradizioni, rotte, paesaggi Paestum 2014 Contents List of Contributors ............................................................................................................. 7 Foreword / Premessa .......................................................................................................... 11 Abbreviations ..................................................................................................................... 13 Luisa Breglia Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 17 Patrick J. Finglass Stesichorus and the West .................................................................................................... 29 Alfonso Mele A proposito di Hespería ..................................................................................................... 35 Fausto Zevi Intervento .......................................................................................................................... 53 Giovanna Greco Cuma arcaica: ruolo e funzione nel rapporto con gli Indigeni ............................................ 57 Giambattista D’Alessio L’estremo Occidente nella Titanomachia ciclica: osservazioni sul del Sole e sul giardino delle Esperidi................................................ 87 Ewen Bowie Stesichorus’ Geryoneis........................................................................................................ 99 Jean-Paul Morel Eldorado. Les Phocéens et Tartessos ................................................................................ 107 Ian Rutherford Paeans, Italy and Stesichorus ........................................................................................... 131 Federica Cordano Un periplo del Mediterraneo con le vacche di Gerione ..................................................... 137 Domingo Plácido Suárez Los confines del mundo en Occidente .............................................................................. 147 Giovanni Cerri L’Ade ad Oriente, viaggio quotidiano del carro del sole e direzione della corrente dell’oceano ............................................................................... 165 Francesco Prontera La geografia dell’Odissea ................................................................................................. 181 Adolfo J. Domínguez Monedero Eubeos y locrios entre el Jónico y el Adriático.................................................................. 189 Daniel Ogden How “Western” Were the Ancient Oracles of the Dead? ................................................. 211 Paola Angeli Bernardini Il viaggio espiatorio di Alcmeone verso una nuova terra .................................................. 227 Juliette de La Genière Nostoi .............................................................................................................................. 237 Serena Bianchetti L’estremo Occidente dei “geografi scienziati” .................................................................. 261 Index Locorum................................................................................................................. 279 General Index................................................................................................................... 295 Author Index.................................................................................................................... 311 17 Introduction Luisa Breglia 1150 1155 These verses from Euripides’ Ion (1147-58), probably also inspired by the description of Achilles’ shield in book XVIII of the Iliad, put the trajectory of Helios’ chariot and that of the star Hesperos in close proximity, thereby testifying the strong association between the zone where the sun can no longer be seen and sunset. In contrast, Phosphoros is simply attributed to Eos. When Euripides represented his tragedy he may have had in mind the representation of the two chariots, Helios and Selene, present on the East pediment of the Parthenon, and it was already known that the evening star, Hesperos, and the morning star, Eosphoros, were one and the same1. This, however, was not always the case. The setting of the sun had been variously conceived as either a disappearance underground or as Helios’ return to a starting point, along the Ocean stream2: perhaps two visions not completely in contrast with each other. In fact, verses 746-51 of the Theogony, which speak about Night and Day that cross at the bronze door, one entering while the other leaves, the house never holding both of them together, seem to stem from conceiving the trajectory of Night and Day as “vertical” movement, while the preceding verses (736-9) seem to evoke the vision of a “horizontal” transit, since in these verses they are considered near the and the of the earth, of Tartarus, of Pontus and of 1) In Hes. Th. 381 Eos is the mother of Eosphoros, Ibycus already identified a single star (fr. 331 PMGF) and the “discovery” of the identity of the two stars, corresponding to Venus was attributed to the Pythagoreans (Apollod. FGrHist 244 F 91; Plin. NH II, 37; cf. West 1980, 206-8). As well as the Parthenon, which would appear to be the “nearest comparison” for a tragedy like Euripides’ Ion, the image of the two chariots recalls Night and Day that appear on the lekythos of the Sappho Painter at the Metropolitan Museum, where Heracles also appears represented while sacrificing at an altar, in an elevated position, perhaps a representation of the hero’s acquisition of the god’s cup/goblet: cf. Ferrari Pinney – Sismondo Ridgway 1981, 141-4. 2) Nagy 1999, 205-7; Ballabriga 1986, passim; Nakassis 2004, 215-33; West 1966, 197-8. 18 Luisa Breglia Uranus. These are verses which have been, and still are, much discussed, also because the two alternate visions also seem to be testified elsewhere3. Posing the concept of Hesperos and of Hesperia as an object of study means, therefore, investigating archaic cosmological and cosmogonical concepts and myth traditions regarding the “limits of the earth” and their progressive “inclusion” into spaces that, piece by piece, became better known thanks to the gradual increase of knowledge about “far distant” countries as a result of navigation and cultural and commercial exchanges. In the Homeric poems and above all , as adjectives, indicate the evening; only in one passage of the Odyssey (VIII, 29) does one find a distinction between and , oriental and occidental; connotes, as it does in Euripides, the place where Helios disappears, whether it be his actual disappearance or if it is meant as a dive into the Ocean ( is the verb often used by Homer4), or a descent under ground, or 5 embarcation on a cup ( , , ) to return towards Ethiopia, where it shall stay until the rise of Aurora (Mimn. fr. 12 West). Hence, the path taken by the sun goes from one world’s end to the other and is situated in a place touching on the subterranean world, in particular Hades. It seems, therefore, that the oldest concept of the world’s end, of the , coincides with that of the zones near or beyond the Ocean, where, in the Odyssey, we find Calypso6, the Hesperides and Atlas, and in Hesiod7, Geryon, Heracles and the Gorgons, and perhaps also the Elysian Fields in Stesichorus8. But these figures which seem to evoke the West can also be located in the East, as is seen in imagery linked essentially to the concept of the Ocean as a limit9. The essays collected in this volume have the scope of identifying, each from a precise point of view, how the traditions connected to epic, in Homer and in the poets of the epic cycle and in the oldest lyric poems, presented these zones, and to seeing parallels in how, from a concept of Hesperos the place of sunset, an extreme populated by monsters and creatures connected to the world of Night (but not only), a vision was developed in which some specific regions were considered the Hesperiai: quite well-defined regions like the place where Aeneas landed after fleeing from Troy, or Libya, the landing place of the Argonauts and of the founders of Euhesperides, or Hiberia or Keltiké. In this process, direct knowledge of the places added to and enriched an imagery already modelled by epic, though not modifying it completely, as, I believe, many essays presented in this volume demonstrate. Besides, the presence of a series of works by archaeologist colleagues, clarifies the state of our recent knowledge of material evidence regarding the arrival zones of the Greeks, probable vectors of heroes and cults of the various “Hesperiai”. Although the term Hesperia neither in the adjectival form nor in the noun form ever occurs as a designation of the vast area that runs from the extreme western point of the 3) West 1966, 197-8: Arrighetti 1975, 146-213; Ballabriga, ibid.; Mondi 1989, 1-41; Johnson 1999, 8-28; Nagy 1999, 205 ff.; Nakassis, ibid. 4) Cf. Hom. Il. III, 322; VII, 131; XI, 263, and Cousin 2002, 25-46. 5) For a discussion of the terms, cf. the paper of G.B. D’Alessio; see also West 1979, 130-48; Plácido 1993, 63-80. 6) Od. I, 50; IV, 498; V, 100 ff.; V, 278; XII, 447-8. 7) Hes. Th. 211 ff.; 270 ff.; 979 ff. 8) Frr. S7; S17; S8; S85 PMGF with a discussion in Lazzeri 2008, 29-94, 314-20. 9) See Ballabriga 1986, passim; Cerri 1995, 437-67. Introduction 19 Peleponnese to the coasts of what, in the historical era, would have been Epirus and Illyria, many indicators make this area a very ancient , linked to the gates of the Sun and to Hades. The most interesting evidence seems to be constituted by the first verses of book XXIV of the Odyssey, where Hermes accompanies the souls of the dead suitors: passing the gates of the Sun and going beyond the White Rock, where a field of asphodel awaits them: recalling the White Island of Achilles, generally located in the East, but perhaps rather at the cliff of Lefkada known by slightly later traditions. The ethnonym Thesprotoi means, as was brilliantly clarified, “god given” (Gottzugeteilt), that is, by the oracle10, and therefore manteis11, and in Thesprotia there was Cheimerion, an entrance to Hades, and an oracle of the dead, inhabited by populations that Thucydides (I, 47-50) also defined as barbaroi. According to a tradition also present, it seems, in the Derveni papyrus12, the Acheloous, which counted as a double of Ocean, flowed there. Further to the South, near the Echinades Islands, the traditions of the Hesiodic poem Ehoie (fr. 150 M-W) locate the Sirens, who the poet considers the daughters of Acheloous13; here again a tradition linked to the Alkmaionis14 placed the destination of Alcmaeon, who, though impure, could arrive here because the land had still not been touched by the sun. And in Apollonia there were also the cattle of the Sun15. In this way there is the presence of a series of data that feature the imagery that we find in other , and it is no wonder that Hecataeus of Miletos located the myth of Geryon here, in a view that seems of Corinthian origin16, in an Erythia perhaps less “wild” than the area of Gades17, where Stesichorus had located the myth. And a version, perhaps contemporary with the same book XXIV of the Odyssey, sets the last voyage of Odysseus18 in Thesprotia itself, the land of manteis. Also Elis and Messenia are characterised as areas linked to Hades: in Elis there was king Augeas, whose name recalls the sun, who owned a treasure, perhaps underground, the work of Trophonius and Agamedes: and according to some, the river Selleeis, double of the Thesprotic Selleeis, flowed in Elis, and also there was a known entrance to Hades here19; also further to the South there were several Pylos already variously identified with the city of Nestor in antiquity; and finally Cape Maleas was one of the four great Greek nekyomanteia20. The area of Cape Maleas is that of Odysseus’ shipwreck: in this way there arises the problem whether a “limit” of the world could be found starting from here and travelling North. And there also arises the problem of the imagery connected to these places, an imagery that mirrors, it would 10) De Simone 1993, 51-4. 11) Reggiani 2011, 113-37. 12) D’Alessio 2004, 16-37; for the Derveni papyrus, c. 23, cf. Tortorelli 2006, 224. 13) Frr. 27-8 M-W. 14) Frr. 9-11 Bernabé. 15) Hdt. IX, 92-5: see also Braccesi – Rossignoli 1999, 176-81 and Braccesi 2001, 23-33. 16) Hecat. FGrHist 1 F 26; see Croon 1952, 49-52. For the Corinthian origins of the tradition see Lepore 1962, 38-64; Hammond 1967, 425 ff., 458 ff. More recently, Ballabriga 1986; Antonetti 2007, 89-111; Angeli Bernardini 2010, 385-409; Foderà 2013 with further bibliography. 17) Ballabriga 1986, 45-53. 18) West 1981, 169-75; Heubeck 1983, 268-73, with further bibliography; Cerri 1995, 437-67; 2002, 149-84. 19) Strabo VIII 3,5; for the various Ephyrai, Apollod. FGrHist 244 FF 179-80: see Calce 2011, 87-91. Ephyra appears in Homer both in Thesprotia and in Elis: cf. e.g. Il. XIII, 298-305; Od. II, 325-8; XIV, 314, to quote only some passages. 20) See the paper of O. Ogden; see also Ogden 2001, passim. 20 Luisa Breglia seem, the imagery connected to the sun which rises or sets21. Much discussion has been made about this similarity of the two opposite extreme limits, with various explanations, from that of a meeting of opposites of G. Nagy22, taken up with a more sophisticated analysis by A. Ballabriga23, to that of a gemination of the horizons, depending on two different concepts of the passage of the sun: one a vertical trajectory, which would appear present in the verses of the Theogony already quoted and perhaps in the Homeric verses regarding the Laestrygonians24, and the “horizontal”, which foresees a return of sun, along the Ocean stream, as we have said. The figure of Augeas is also to be added to the different elements that allow verification of analogue concepts and analogue figures between East and West: his name recalls the rays of the sun; he has a treasure25, which could be analogous to the Golden Fleece of Aeëtes, and the Iliad names one of his daughters as Agamedes (a name echoing that of Medea), an expert in poisons26; his grandson’s name, Polyxenos, is an epiclesis of Hades27. Furthermore, the relationship between Augeas and his treasure could make one think of an underground descent, no different to that made by the sun, not to mention his stables and his cattle that allow identification of him with Helios, robbed by Alcyoneus or by Porphyrion28. Thus, one would find a double of Aeëtes29, like Circe a child of Helios, located to the West30. The entire Illyrian and Thesprotian coast, and that further to the South running to the Ionian islands and the North-Eastern Peleponnese, seems to look onto the Ocean (if the Acheloous is considered, as it still was by seventh century writers, Ocean). If one remembers the siting of Circe in the Odyssey as near the Ocean, and that, as West has shown, Odysseus’ voyage retraces that of the Argonauts, one may deduce that the Northern limit of the Italian peninsula was not known to the poet of the Odyssey. For confirmation one could sustain that according to Herodotus (I, 163) only the Phocaeans discovered that the Adriatic was a closed sea, and the fact that the route that Odysseus had to follow to arrive at Ithaca, following the advice of Calypso, keeping, that is, the Bear on his left, would lead one to think that there was no land between Ogygia (in the West) and Ithaca (in the East). The foundation of Massalia could have marked the change in conceptualisation of the extension of the area. 21) Erytheia, near the Hesperides and the home of Geryon in Stesichorus, was also the place from where Alcyoneus or Porphirion had stolen the cattle of the Sun (Pind. Nem. I cum scholiis); see Ballabriga (1986), which mirrors a similar situation for snowy Dodona (Il. II, 748-55; Od. XIV, 316-7 and 327-30), even though there may be other explanations of these different accounts: see Calce 2011, 29-33. 22) Nagy 1999, 205-7. 23) Ballabriga 1986, quoted above, n. 7. 24) Od. X, 82-6. 25) Eugam. Teleg.: Argum. and fr. 2 Bernabé. 26) Il. II, 615 ff.; XI, 737; Arrian. FGrHist 156 F 61a; Eust. ad Hom. Il. III, 317; the name is already present in the Mycenean tablets of Pylos: PY An 192; Jo 438,23; Ta 711,1; for Augeas son of Helios Theocr. XXV, 54, Paus. V, 1,9; for the archaic Elian traditions, see Nobili 2010, 171-85, even though not very convincing. 27) Aesch. Suppl. 144; Stegemann 1952. 28) Cf. n. 20. 29) Cf. A.R. I, 172. 30) The Sun evokes royalty. Besides other examples that could be made (Atreus’ ram, among others), one only has to think Herodotus’ account of Perdiccas at Hdt. VIII, 173: here the king tells the young servants who ask for recompense to take what comes through the window: only the youngest understands that this means the sun’s rays. This is, therefore, a very old concept, where the king takes on himself all the burden connected to looking after the community, a community’ however, already connected to agriculture and the passage of the seasons more than to grazing livestock. Introduction 21 One may also ask the question, and this remains an open problem, how much these concepts owe to knowledge of the Black Sea, where the voyage of the Argonauts takes place. Recently, M.L. West31, taking up the hypothesis of K. Meuli32, has stressed how a series of episodes from the Odyssey may not only go back to the ancient Argonauts, but mirror geographical realities present in the Orient. This deals with an imagery that still continued to influence Mimnermus who, in fr. 11a West, mentions the sun’s rays as an underground treasure. These traditions, already widespread in the Milesian area at the end of the seventh century or only a little later, would have influenced the imagery of the Odyssey and perhaps, one may imagine, also those local epic accounts linked to the most ancient Thesprotis33 and to the Telegony, especially to Thesprotis, where Orphic traditions34 were present, which could recall, besides the location of Theseus’ and Pirithous’ descents into the Underworld in Thesprotia35, that of Orpheus himself36, and the important role that he played, as West has demonstrated, in the oldest Argonaut traditions37. But both the voyage of the Argonauts, and the Odyssean plane also mirror an initiatory itinerary, the one testified by Oriental myth and later on still present in the world of fables38: the hero must arrive at the end of the earth and overcome trials so as to be able, in the end, to win his kingdom, sometimes marrying the daughter of the local king: these “models” have also been referred to in the search for frameworks for the representations of the most ancient epic and poetry: like the voyage of Odyssey, the feats of Heracles also follow this model39, and it is not by chance, that in the story of the capture of Geryon’s cattle, to obtain the cup of Helios, necessary for arriving at Erytheia, he had a “helper”, Nereus, in Panyassis’ version (fr. 9 Bernabé) while in Peisander’s version (fr. 5 Bernabé) the role of intermediary was represented by Oceanus; both talismans and intermediaries are indispensable in narrations of initiation, to carry the action to completion, as also occurs in the myth of Perseus. Today’s Straits of Gibraltar shall thus become the limit of an Oecumene linked to the travel experiences of the Euboeans (probably together with the Phoenicians) and the Phocaeans: here Stesichorus would locate the monster Geryon, the Gorgons (already connected to the Hesperides in Th. 274-5), Orthus, brother of Cerberus, the Hesperides and make the world of the dead appear beyond them; it is not by chance that the cattle of Hades also pasture at Erytheia and, as has been observed, the red colours seem to recall the Underworld40. Heracles is a civilising hero, as is known, and is also the young man who has to carry out the labours he has been set. He fights the monster with arrows (the arms that are his own and that set him off as young), and in Stesichorus, though the scene of action shows traces 31) West 2005, 39-64. 32) Meuli 1921, passim. 33) Cerri 2022, 149-84; Grossardt 2003, 211-53; many students think that a poem called “Thesprotis” never existed: see Davies 2001, 83-6; West 2013. 34) Clement of Alexandria attributed this work to Mousaios: Eugam. Teleg. T 3 Bernabé; see Debiasi 2004, 249 ff.; see n. 33. 35) Plut. Thes. 31 e 35 (who quotes Philoch. FGrHist 328 F 18a); Paus. I, 17,4. 36) Paus. IX 30,6; also in the representation of the Knidian Treasury at Delphi Orpheus is next to Persephone: Paus. X, 36. 37) West 2005. 38) Propp 1972, 233 ff. 39) Burkert 1979, 185 ff.; d’Agostino 1995, 7-13. 40) Davies 1988, 277-90; Burgess 1999, 171-210. 22 Luisa Breglia of new knowledge, especially Phocaean41, it also seems to show traces of the description of the ends of the earth present in Homer and Hesiod. But the places of sunset were later located in various zones and one may ask oneself again, how much these different locations owe to the cosmogonic concept that has just been stressed and how much to the various Greek peoples that arrived from the East: Euboeans, and also Locrians, as we shall see, Corinthians and Phocaeans. “Ilioupersis according to Stesichorus” is what one reads on the Tabula Iliaca Capitolina42; on the lower right there is Aeneas with Anchises on his right shoulder and, as well as other illuminating inscriptions, one may read “Hesperia” as the destination of the hero’s voyage, while a figure at the bottom is identified as Misenus. One of the main themes addressed in this volume is that of this representation, and not only the problem of the real paternity of Stesichorus for what regards the story represented here: that the sculptor Theodoros names Stesichorus and represents himself as a double of Epeius, the constructor of the Trojan horse, has been brilliantly demonstrated by P.J. Finglass, who has also shown how Stesichorus gave value to Epeius, a hero who has roots mainly in the West, at Lagaria and then at Metapontus and Pisa43. This seems to lead to the perception of a tendency in Stesichorus towards giving value to heroes connected to the West, like Aeneas. A problem remains: what was indicated by Hesperia in Stesichorus? Did it already indicate Italy, as documented in later traditions, Agathyllus and Dionysius of Halicarnassus, but perhaps also previously in Hellanicus (FGrHist 4 F 111)? When and how did this peninsula, certainly to the West, become Hesperia? Undoubtedly Hesperia/Italy seems less wild and monstrous than the far West in which Geryon is found and in fact it is connected to the plane of Aeneas, and had a precedent in the plane of the Odyssey, as testified by the presence of Misenus himself, originally the Homeric hero’s companion44. The Hesiodic tradition45 had already located Circe here, and in Homer Circe was not very distant from Hades: a fact that had authorised the Euboeans arriving at Cyme to locate a nekyomanteion there, facilitated in this act by the sulphurous exhalations and the presence of volcanic activity. Besides, the problem does not only concern Italy. Other areas, Iberia in particular, and, in a tradition going back to Alexander Polyhistor46, Libya, are also called “Hesperia”. Some of 41) Antonelli 1995, 11-24 has also concentrated on knowledge due to Euboean voyages. But the river Anthemus and Mt. Abas which he refers, appear in Apollod. II, 5,10, and the assonance with the island of Anthemoessa of Hesiod’s Sirens (fr. 27 M-W = 24 Most) does not appear a sufficient motive for this claim: if the Sirens were alluded to by this name, on would think of them as divinities in some way connected to the world beyond and not necessarily Euboean. Mt. Abas could evoke Euboea, but a hero called Abas also occurs at Argos. If we are now sure of the Euboean presence in the straits, and in the area beyond them, (Huelva in particular), it does not mean that this knowledge must have been immediately employed in the representations of a place “at the ends of the earth”: in Stesichorus they seem to share imagery depending a great deal on Hesiod’s Theogony, which placed Atlas on the threshold of the Underworld near the Hesperides, and imprecise knowledge of Southern Iberia. 42) See the paper of P.J. Finglass; see also Finglass 2013. 43) Mele 1993-1994, 71-109. 44) For these problems, see the paper of A. Mele. 45) Th. 1022 ff.; the dating of these verses is controversial, cf. West 1966, ad loc.; also for the verses of the Nekyia of Od. XI, 114 ff., the dating, as has been stressed (cf. n. ) is controversial any many (among whom Page 1955) lower it to the sixth century BC. 46) FGrHist 273 F 124. Introduction 23 the names, for this region he calls , are interesting: Okeania, Eschatià, as well as Hesperia and Ophiousa (which could come from the snake set to guard the apples of the Hesperides), Aithiopia and Ammonis among others. But Eschatià and Okeania indicate images often connected to the West and in particular with the Hesperides, daughters of Night, situated there in Hesiod’s Theogony, beyond the Ocean. In another fragment, the 360 M-W (= 299a-b Most) they have the names Aigle, Erytheia and Hesperethousa. Aithiopia recalls the Ethiopians already with a double location in Homer, near the rising or the setting of the sun, (a case of coincidentia oppositorum, according to Ballabriga’s interpretation47). According to the verses of Apollonius of Rhodes (IV, 1396 ff.), also taken up by Diodorus48, a passage of the Argonaut’s voyage, as well as Atlas, the Hesperides and their garden, was also situated in Libya. A set of mythical figures seems, therefore, to mark the West, and they are found in those areas identified by Hesperia: the Hesperides, Atlas, Geryon, the Gorgons, as far as Iberia and Libya are concerned, Odysseus and also Heracles who takes Geryon’s cattle, for Italy. (at the moment my own speech does not take into account the relative chronological dates of these traditions). Already starting from Titanomachia (T 8 Bernabé) Helios arrives at Erythia by crossing the Ocean in the cup of the sun49. As should be clear from what has been said so far, if the “conquest”/capture of Geryon’s cattle has the hero’s conquest of immortality as its final significance, if Geryon himself, with his herd of cattle that represents the souls of the dead50, is a double of Hades, the siting of the various Hesperiai, taken as territories now well defined and no longer only known as zones at the confine, also ends up as being connected with Hades or, at least, to those heroes that arrived at the ends of the world. Though without a precise topographical location in the Odyssey, the plane of Odysseus has the entrance to Hades among its landing points (almost all of these in some way at the confine), which the Euboean navigations situate at Cyme. The Odyssey and an ancient poem about Heracles are therefore at the basis of these later sitings, as is clear from Hesiod’s Theogony, but they are obviously treating concepts and myths already widespread and with a wide audience in very ancient times. Hence comes the need to address the various problems of the myths connected to Geryon, to the Hesperides and the various locations of these, including those in the East, since the location of Hades itself is sometimes found in the East, as also occurs for nekyomanteia. Therefore, there is also the need to compare literary information with information deriving from archaeology regarding the Greek presence and navigation in the Western Mediterranean, in Libya, in Spain and in Italy: these navigators and the Greeks who arrived in the West were probably the origin of the reelaborations of the various myths, in a continuous mythopoietic process. These are the themes addressed in these essays and I hope that they allow making some advance on these debated problems. 47) Ibid. 48) IV, 26: for the problems posed by the conquest of the apples of the Hesperides see recent work of Angeli Bernardini 2011, 159-76; for the Gorgons in Libya: Eur. Bacch. 990-1; Hdt. II, 91. 49) Helios crosses the Ocean on a , see Vian 1952, 142 ff.; D’Alessio. 50) Davies 1988, ibid. 24 Luisa Breglia The problems set by the works of Stesichorus were the starting point, and this not only because his Geryoneïs seems to fix a series of elements that would later also identify the other Hesperiai, but also because in his Ilioupersis Stesichorus seems to have been the first to identify Italy as Hesperia. For Stesichorus, therefore, one poses the problems of how much his work is influenced by the descriptions of information coming from Euboean and Phocaean navigation, of who was the audience of his work, of how he, a Chalcidean from Imera related to the reality close to him. The contributions of E. Bowie and I. Rutherford and in part that of G. Cerri seek to give answers to these questions, starting by comparing the Geryoneïs with other archaic works, studying the forms (peana) that some Stesichorean works could have taken (a piece of information to which is connected the problem of their diffusion, also through great religious festivals), and finally that of the ultimate addressees of Stesichorus’ Palinode, connected perhaps to the moment of the Battle of the Sagra. Furthermore, still in relation to Stesichorus and to his Ilioupersis, we owe to P.J. Finglass’s text, not only the certainty that the term “Hesperia” present on the Tabula Iliaca Capitolina comes from this author, but also the definition of Epeius’s role in this work, where he was celebrated as the builder of the Trojan horse and therefore also as he who brought about the fall of the ancient city. A. Mele, developing the reading of Finglass, was able to clarify, discussing with F. Zevi, the role that Misenus must have had and the way in which this hero, originally connected to Odysseus, could become the companion of Aeneas in Stesichorus. The problems of the ends of the world and the voyages of Helios and Heracles along the Ocean are addressed by the accurate analysis of G.B. D’Alessio on the cyclic Theogony, while also in relation to Heracles and Geryon F. Cordano expressed his interpretation of the voyage of the hero along the coasts of the Mediterranean. The extension of the geography of the Odyssey and the problem of the presence and location of Hades and of Helios in the East, as mentioned above, are addressed from two different points of view in the texts of G. Cerri and of F. Prontera: and again the problem of the great nekyomanteia and their geographical locations, of the landscapes in which they are situated, of the realien underlying them are the basis of the contribution of D. Ogden. P. Angeli Bernardini’s text is part of the investigation about the relationship journey of the Sun/world beyond, with the examination of the hero Alcmaeon and of Amphilochus, founders of a land lived as “extreme”, a concept reelaborated as Corinthian propaganda and as a “manifesto” for the occupation of those territories on the part of Corinth, behind which, I believe, perhaps one may still perceive, in any case, the existence of an archaic concept of this zone as the “end of the world”. The relationship Euboeans-Locrians in colonisation, present in various, sometimes overlooked, testimonies, allows A.J. Domínguez Monedero to clarify how the Locrians, that were already divided into and in the motherland were, may have imported the concept both into the Northern Mediterranean (Locri Epizephyrii) and to the coasts of the Southern Italy (Euhesperides). G. Greco presented and discussed the latest archaeological findings at Cyme, landing point of Aeneas in the Ilioupersis, while J. de la Genière started a rereading of the archaeological information of his excavations of Amendolara identifying it as the Lagaria founded by Epeios. J.-P. Morel, again taking up his excavation findings, traced an image of the area of the “Columns of Hercules”, as the land of riches, the “El Dorado” of the Time, an image that certainly contrasts that of Stesichorus, but that we can understand in the light of the Introduction 25 beautiful pages that D. Plácido Suárez dedicates to the concept of , as places where there is everything that is not “at the centre”, everything that is monstrous, but also the marvellous. These pages stress how is in fact a political concept connected to the opposition centre/periphery, that is a constant that accompanies every further enlargement of the space beyond the ends of the world. S. Bianchetti also states in his text how, after a long process, these oceanic spaces are finally conquered in the Geography of Strabo. There was already a vast bibliography on these themes, to which some authors of these essays have contributed in other periods. The problem of the , in the relationship Argonautica/Odyssey, that of the relationship of the epic cycle with the two greater works, the Iliad and the Odyssey, all have a long tradition of studies behind them, even though recently there has been a new attention to them, motivated by new questions that we always pose to the ancient texts. The points on which these essays focus, and especially those creating the idea of the West as the location of sunset, connecting immediately to Hades, and that of why Hesperides may indicate well-defined territory, reconnect in these earlier studies and, it seems to me as editor, that they also open up new study prospects and help to pose new questions and respond to others. This, I think, should be the sense of our work as ancient historians, and I believe that the works collected here perform this task admirably. 26 Luisa Breglia Bibliography Angeli Bernardini P. 2010, ‘Eracle: una biografia eroica tra epos arcaico, poesia lirica e tradizioni locali’, in E. Cingano (ed.), Tra panellenismo e tradizioni locali. Generi poetici e storiografia, Alessandria, 385-409. Angeli Bernardini P. 2011, ‘Eracle e le Esperidi. Geografia del mito nelle forme poetiche e mitografiche greche arcaiche e tardo-arcaiche’, in A. Aloni – M. Ornaghi (eds.), Tra panellenismo e tradizioni locali. Nuovi contributi, Messina, 159-76. Antonelli L. 1995, ‘Sulle navi degli Eubei: immaginario mitico e traffici di età arcaica’, Hesperìa 5, 11-24. Antonetti C. 2007, ‘Epidamno, Apollonia e il santuario Olimpico: convergenze e discontinuità nella mitologia delle origini’, in D. Berranger-Auserve (ed.), Épire, Illyrie, Macédoine, Mélanges offertes au Professeur P. Cabanes, Clermont-Ferrand, 89-111. Arrighetti G. 1975, Esiodo. Letture critiche, Milano. Ballabriga A. 1986, Le Soleil et le Tartare, Paris. Braccesi L. 2001, Hellenikós kolpos. Supplemento a Grecità adriatica, Roma, 23-33. Braccesi L. – Rossignoli B. 1999, ‘Gli Eubei, l’Adriatico e la Geografia dell’Odissea’, RFIC 127, 176-81. Burgess J. 1999, ‘Gilgamesh and Odysseus in the Other World’, Echos du monde Classique 43, 171-210. Burkert W. 1979, Structure and History in Greek Mythology and Ritual, London. Calce R. 2011, Graikoi ed Hellenes. Storia di due etnonimi (Diabaseis 3.2), Pisa. Cerri G. 1995, ‘Cosmologia dell’Ade in Omero, Esiodo e Parmenide’, in R. Cantilena (ed.), Caronte. Un obolo per l’aldilà (PP 50), 437-67. Cerri G. 2002, ‘L’Odissea epicorica di Itaca’, MediterrAnt 5, 149-84. Cousin C. 2002, ‘La situation géographique et les abords de l’Hadès homérique’, Gaia 6, 25-46. Croon J.H. 1952, Herdsman of the Dead. Studies on some cults, myths, and legends of The the ancient Greek colonization-area, Utrecht. D’Agostino 1995, ‘Eracle e Gerione: la struttura del mito e la storia’, AION(archeol) 2, 7-13. D’Alessio G.B. 2004, ‘Textual Fluctuations and Cosmic Streams. Ocean and Acheloios’, JRS 124, 16-37. Davies M. 1988, ‘Stesichorus’ Geryoneis and its Folk-Tale Origins’, CQ 18, 277-90. Davies M. 2002, ‘The Folk-Tales Origin s of the Iliad and Odyssey’, WS 115, 5-43. Debiasi A. 2004, L’epica perduta: Eumelo, il Ciclo, l’Occidente, Roma. De Simone C. 2003, ‘Il santuario di Dodona e la mantica greca più antica. Considerazioni linguistico-culturali’, in L’Illyrie méridionale et l’ Épire dans l’ Antiquité II, Clermont-Ferrand. 27 Introduction Ferrari Pinney G. – Sismondo Ridgway B., ‘Heracles at the Ends of the Earth’, JHS 101, 141-4. Finglass P.J. 2013, ‘How Stesichorus Began His Sack of Troy’, ZPE 185, 1-17. Foderà V. 2013, ‘Gerione in Ecateo di Mileto (FGrHist 1 F 26): alcune considerazioni per una nuova interpretazione’, Rationes Rerum 1, 55-68. Grossardt P. 2003, ‘Zweite Reise un Todd es Odysseus. Mündliche Traditionen und Literarische Gestaltungen’, in S. Nicosia (ed.), Ulisse nel tempo. La metafora infinita, Venezia, 211-53. Hammond N.G.L. 1967, Epirus. The geography, the ancient remains, the history and the topography of Epirus and adjacient areas, Oxford. Heubeck A. 1983, Omero. Odissea, libri IX-XII (trad. di G.A. Privitera), Milano. Johnson D.M. 1999, ‘Hesiod’s Description of Tartarus (“Theogony” 721-819)’, Phoenix 53, 8-28. Lazzeri M. 2008, Studi sulla Gerioneide di Stesicoro, Napoli. Lepore E. 1962, Ricerche sull’antico Epiro. Le origini storiche e gli interessi greci, Napoli. Mele A. 1993-1994, ‘Le origini degli Elymi nelle tradizioni di V secolo’, Kokalos 34-35, 71-109. Meuli K. 1921, Odyssee und Argonautika, Berlin. Mondi R. 1989, ‘ and the Hesiodic Cosmogony’, HSCPh 92, 1-41. Nagy G. 1999, The Best of Achaeans, Baltimore (2nd ed.). Nakassis D. 2004, ‘Gemination at the Horizons: East and West in the Mythical Geography of the Archaic Greek Epic’, TAPhA 134, 215-33. Nobili C. 2010, L’Odissea e le tradizioni peloponnesiache, Pasiphae 3, 171-85. Ogden D. 2001, Greek and Roman Necromancy, Princeton-Oxford. Page D.L. 1955, The Homeric Odyssey, Oxford. Plácido Suárez D. 1993, ‘Le vie di Ercole nell’estremo Occidente’, in A. Mastrocinque (ed.), Ercole in Occidente, Trento, 63-80. Propp V. 1972, Le radici storiche di racconti di fate, Milano (it. transl. of the original edition 1946). Reggiani N. 2011, ‘I manteis della Grecia Nord-Occidentale’, in L. Breglia – A. Moleti – M.L. Napolitano, Ethne, identità e tradizioni: la “terza” Grecia e l’Occidente (Diabaseis 3.1), Pisa, 113-37. Stegemann W. 1952, s.v. ‘Polyxenos’, RE XXI, coll. 1857-9. Tortorelli Ghidini M. 2006, Figli della terra e del cielo stellato, Napoli. Vian F. 1952, La guerre des Géants. Le mythe avant l’époque hellénistique, Paris. West M.L. 1966, Hesiod. Theogony, Oxford. West M.L. 1979, ‘The Prometheus Trilogy’, JHS 99, 130-48. West M.L. 1980, ‘The Midnight Planet’, JHS 100, 206-8. West M.L. 2005,‘“Odyssey” and “Argonautica”’, CQ 55, 39-64. West M.L. 2013, The Epic Cycle, Oxford. West S. 1981, ‘An Alternative nostos for Odysseus?’, LCM 6, 169-75.