Lecture Slides - Academia Sinica

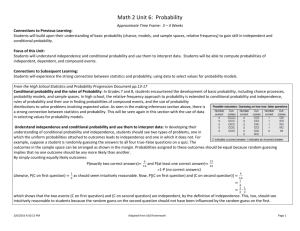

advertisement

The Optimal Allocation of Risk James Mirrlees Chinese University of Hong Kong At Academia Sinica, Taipei 8 October 2010 Risky contracts Insurance Outcome conditional on accident Pensions Outcome could be conditional on capital market performance; or on GDP “Securities” conditional on companies' performance or default Loans conditional on own experience – might default Optimality Arrow and Debreu are supposed to have shown that an optimum can be implemented by a full set of free markets in securities, with income redistribution. Does not even need to be a full set. Second-best considerations imply the need for taxes on goods and services and securities, but do not affect the main Arrow/Debreu argument. But the claim is wrong. Moral Hazard Familiar objection. People's actions are not always observable, or deducible from outcomes, and contracts cannot be made conditional on them. Intuitively, one guesses contracts should be conditional on outcomes, as imperfect proxies for actions. But that is not enough. Optimal contracts with moral hazard. Let insurers sell contracts to people with moral hazard. The contracts should pay conditional on all observables that are influenced by, or influence the hidden action. The contracts exclude clients from other contracts conditioned on these observables. Insurers maximize expected profit, and compete. An optimum can be achieved with these contracts. Feasibility? CDOs. These are traded contracts, i.e. there is no exclusion. Wrong incentives for the client, in this case a mortgage lender, for example. Health insurance. Coinsurance proposed. But thought that people can still insure the coinsurance payment. Then coinsurance has no effect, and incentives are wrong. Conclusion? State monopoly? Multiple relevant observables Car insurance. Miles driven is observable, for some contracts – e.g. buying petrol. Clearly associated with accident risk. It is too costly for insurers to include miles driven in contracts. That can be corrected, imperfectly, with higher petrol taxation. In many cases, complexity rules out intervention of this kind. Case for regulation. Another flaw in Arrow/Debreu: ignorance. Arrow/Debreu uses individual preference, e.g. expected utility. – in terms of whatever probabilities individuals happen to believe. Surely welfare must be judged by outcomes, if not entirely, then mainly. Two people, identical preferences, opposite beliefs – sun for sure, rain for sure. They will trade so that one starves if rain, the other if sun. Plainly not an optimum. Back to fundamentals Karl Borch considered allocation where everyone has the same beliefs. Aggregate output varies across states of nature, and has to be allocated to individuals. He showed that each individual's allocation is an increasing function of total output. It can be achieved with Arrow/Debreu securities. There would be no short trading. If probabilities differ, utilities are the same, equal sharing of output is optimal: i.e. no consumer choice. The general problem Two major difficulties. To define optimality, one must have true probabilities. One feels these are not always known (though since they should correctly describe uncertainty, they should allow for that ignorance). Anyway, fully informed people will disagree. Secondly, it is technically challenging. Varied risk preferences. d is tr ib u te d w ith d e n s ity f.P a r a m e te rr ,d e n s ity g . r ty p e h a su tility u (( x ,rr ) ,) . M a x im iz e (( x ,rrf ) ,)( )() grd d r u s u b je c tto ,rf )( )() grd d r y x( a n d u (( x ,rr ) , ) u (( x ',r') ,r )f o ra ll ,r , ',r' Simpler version: x scalar, no resource constraint. ( D ) :xr ( ,) m a x u ( x ,) r C o m p a r e ( S ) :z m a x ( z ,). r f g d d r ( z ,) r g . d r u u A p p r o x i m a t e f o r s m a l l v a r i a n c e s .R o u g h l y : ( S ) b e a t s ( D ) i f t h e v a r i a b i l i t y o f r i s l e s s t h a n t h e v a r i a b i l i t y o f. If second-best taxation creates optimal incentives for labour supply, incomecontingent variability of r may be quite small, relative to belief-variance. 11 Varying risk preferences In reality people have different false beliefs, and also different risk preferences, and they find themselves with different prospects – hence hedging and insurance seems desirable. One can ask when it is desirable to restrict choice, e.g. by suppressing such gambling as (some kinds of) CDSs. Answer (roughly): when the variance of riskpreferences is less than the variance of probabilities. Really, it should depend on the individual gambler's prospects, hard to observe. 12 Policy? The conclusion is that in certain circumstances, probably many, though difficult to identify, government should ensure that certain kinds of trades should not take place. The technical theorem so far gives little help in identifying asset classes that shoul be severely regulated. The constraint might take the form of saying that only certain kinds of contracts should be traded. Prohibiting short trading is an example. And it may be a case for prescribing the form of pension contracts. 13