Module 10

advertisement

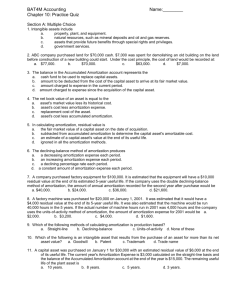

FA2: Module 10 PPE and intangible assets: Depreciation, amortization and impairment 1. Amortization 2. Impairment 3. Goodwill impairment 1. Amortization of capital assets Since long-lived assets provide benefits over several years, the cost is allocated (matched) to the periods in which service are received from (revenues and cash flows are generated by) the asset. Amortization is called: Depreciation Depletion Amortization When referring to: Property, plant & equipment Natural resources Intangible capital assets Amortization expense is not a reflection of a decline in market value of the asset. Amortization expense is not a cash outflow. Capital assets with an indefinite useful life (e. g., land, some intangibles) are not subject to amortization. Calculating amortization 1. Determine acquisition cost = purchase price + any expenditures reasonable and necessary to put the asset into service. 2. Estimate useful service life and residual value (expected value at end of useful service life, often assumed to be zero for convenience). Note that the asset’s physical life may extend beyond its service life. 3. 3. Decide upon the pattern of revenue generation of asset (i. e., select an amortization method): – Straight-line – Diminishing-balance (Declining-balance) – Units-of-production or units-of-use Amortization methods 1. Straight line method Calculation of amortization expense = (Cost - residual value)/Estimated service life Comments • simple and easy to use, • by far the most popular amortization method. • amortization expense is the same in every year (except perhaps years of acquisition and disposal) • appropriate if asset provides constant level of benefits throughout its useful life Amortization methods 2. Diminishing-balance (declining-balance) Calculation of amortization expense = Asset book value (cost – accumulated amortization) × rate • a type of “accelerated” amortization, generating higher expense in early years of the asset’s life • Appropriate if asset efficiency and earning power decline as the asset ages • Popular form is double-diminishing-balance (DDB), where rate = (1/useful life in years) X 2 • Stop amortizing once asset book value equals its residual value • Used by Canada Revenue Agency (CRA) for capital cost allowance purposes Amortization methods 3. Amortization based on units (e. g., units-ofproduction) Calculation of amortization expense = Units realized this period X unit rate, where Unit rate = (cost-residual value)/est. total units. Units is a measure of capacity of the asset, either in terms of service (e. g., hours of operation, kilometers) or production (e. g., finished goods produced). • Many argue that this method provides the best matching of the cost of the asset with the benefits derived from it. • The units-of-production method is typically used to record depletion of natural resources. Example: Machine Ltd. Machine Ltd purchased a machine on June 30, 20x3 for $50,000. It is estimated that the machine will have a $10,000 residual value at the end of its service life of 10 years (or approximately 10,000 operating hours). Depreciation is computed to the nearest month. Compute depreciation expense for 20x3 and 20x4 (assume a December 31 fiscal year end) using each of the following methods: a) straight-line b) units-of-production based on working hours (hours of operation were 1,000 in 20x3 and 1,500 in 20x4) c) double-diminishing balance Which method should be used? Generally, the preferred method is the one that best reflects the benefits the asset generates. If no single method is better than the others in this regard, the preferred method is the simplest one (usually, the straight-line method). 200 Canadian public company amortization methods 2006 Straight-line (SL) only 95 Diminishing-balance (DB) only 3 Units-of-production only 11 SL and units-of-production 42 SL and DB 32 Units-of-production and DB 5 SL, DB and units of production 1 Changes in amortization Companies may (and should) periodically revise estimates used in the amortization calculation. Specifically, the estimated residual value may change; the estimated useful life may need to be revised; or the pattern of use of the asset might change, implying the need to change the amortization method. Accounting for a change in estimate is done prospectively (i. e., there are no changes in previous years’ amortization). The appropriate treatment is to amortize the remaining book value less the revised estimate of the residual value over the (updated) remaining useful life. Example: G and S Moving Company The G and S Moving Company has one truck, whose original cost was $23,000. Its estimated residual value was $3,000 and its estimated useful life was 4 years. At the end of two years, its net book value was $13,000 ( G&S uses straight-line depreciation). After reviewing the use and current condition of the vehicle, the company now believes that the total useful life of the truck will be 5 years, after which its estimated residual value will be $1,000. Required Show the entries to record depreciation expense for year 3. 2. Impairment Long-lived assets stay on the company’s books for many years, but their ability to generate cash flows can change due to environmental factors. Companies must watch for indications that there has been an impairment, a situation in which the recoverable amount of an asset or group of assets has declined and, if necessary, record an impairment loss. Impairment losses An impairment loss occurs if the carrying value of an asset or group of assets exceeds the recoverable amount. Carrying value = cost less accumulated depreciation less accumulated impairment losses Recoverable amount = (1) fair value less cost to sell, or (2) present value of cash flows from future normal use of asset, whichever is higher Cash-generating units Impairment tests are typically applied to cashgenerating units, the smallest group of assets in the organization that generates cash flows that can be distinguished from the cash flows of other assets or groups of assets. If an impairment loss is identified with a particular cash-generating unit, the total impairment loss is allocated to the individual assets within the group. Steps in impairment testing 1. Identification of an asset or cashgenerating unit. 2. Review of external and internal impairment indicators. 3. If required annual testing (goodwill, indefinite life intangibles) or if indication of impairment, measurement of recoverable amount. 4. If impairment, write down to recoverable amount and allocate impairment loss. Impairment indicators 1. Significant change in business environment 2. Physical damage to asset 3. History of operating and/or cash flow losses 4. Probability > 50% that company will retire or dispose of asset earlier than planned 5. Loss of patent infringement lawsuit that has implications for overall operation Allocation of impairment loss If the loss is associated with a single asset, charge all of the loss to that asset. If the loss is associated with several assets in a cash generating unit, loss is prorated among assets based on carrying value. Dr. Impairment loss Cr. Accumulated depreciation – Asset A Cr. Accumulated depreciation – Asset B etc. Limits to impairment loss allocation 1. No asset can be written down to a carrying value less than zero. 2. No asset should be written down to a value less than the higher of its fair value less cost to sell or its value-in-use, as long as this value is readily determinable. Impairment losses can be reversed up to original value. Reversal is allocated to individual assets, prorated on carrying value of the assets in the group. Example: A10-25 3. Goodwill impairment Use the same approach as for cash generating units without goodwill (except that goodwill must be tested for impairment every year). Impairment losses are allocated first to goodwill until goodwill reduced to zero, then allocated to other assets in normal fashion. Impairment losses charged to goodwill cannot be reversed. Example: A10-26