FNCE 4070: FINANCIAL MARKETS AND INSTITUTIONS Lecture 9

advertisement

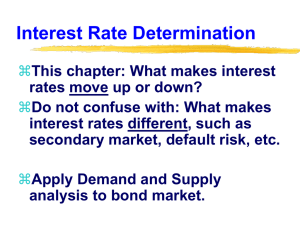

FNCE 4070: FINANCIAL MARKETS AND INSTITUTIONS Lecture 9: Global Debt and Equity Markets With a Discussion of the Globalization of Financial Markets and the Implications of Global Markets for Borrowers and Investors Where is this Financial Center? Arab Spring Risk. Cairo stock market closed from January 27, 2011 to March 23, 2011 Long Term Risk: Investing in the Japanese Stock Market January 1990 – April 2012 -75% January 1984 – January 1990 +270% Fads in Equity Markets January 2008 – December 2008 -61% January 2006 – January 2008 +275% January 2000 – January 2006 -17% Importance of Capital Markets to World Economy World's Capital Market as a Percent of World GDP 500.00 450.00 439.62 418.27 401.50 400.00 350.00 330.60 358.87 369.24 370.29 397.50 361.80 300.00 250.00 200.00 150.00 100.00 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 World's Capital Market % of World GDP 2008 2009 2010 Institutional Arrangements in Corporate Funding The historical institutional patterns of corporate borrowing in various countries have influenced the development a country’s bond markets and equity markets. In Japan and Germany, companies have relied less on equity markets for funds than their counterparts in the U.S. In both of these counties, banking has been a relatively more important source of funds. In Europe, the close ties between banks and their corporate clients hindered the development of a European corporate bond market. That changed, however, with the launch of the euro in 1999, which promoted the development of Europe’s bond market. Importance of Banking Markets for the U.S., Japan and Germany Banking Assets as a % of Country’s GDP 250.0 Banking Assets as a % of Country’s Capital Markets 60.0 50.0 200.0 40.0 150.0 30.0 100.0 20.0 50.0 10.0 0.0 0.0 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 U.S. Banking % GDP U.S. Banking % Capital Market Germany Banking % GDP Germany Banking % Capital Market Japan Banking % GDP Japan Banking % Capital Market Changing Corporate Capital Structures Japan, Germany & the U.K. Changing Debt/Equity Ratios, 1977 - 1985 During the early post war years, Japanese corporation relied heavily on banks and the bond markets to finance their capital structures. In the 1970s, Japanese corporate debt to equity ratios were 4 times as high as that of U.S. companies. But, by the late 1980s, corporate Japan and the U.S. had similar leverage ratios. Germany continued to rely heavily on its banking market. The U.K. paralleled the U.S. during this time. Germany Japan Changing Nature of the Global Bond Market Historically, the U.S. bond market dominated the global bond market, with the U.S. market representing a key source of financing for U.S. and foreign corporations. However, since the expansion of the European Union and the advent of the Euro-Zone, Europe’s importance in the global bond market as grown. In 2002, the U.S represented 43.7% of the world’s bond market; the European Union represented 29.4%. By 2010, the U.S. share of the global bond market had fallen to 34.3% and the European Union’s share had grown to 32.9%. In 2002, the U.S represented 53.8% of the world’s private bond market; the European Union represented 29.2%. By 2010, the U.S. share of the global private bond market had fallen to 40% and the European Union’s share had grown to 38.9%. Trends in Global Bond Markets Percent of Total Bond Market 45.0 Percent of Private Bond Market 60.0 55.0 40.0 50.0 45.0 35.0 40.0 35.0 30.0 30.0 25.0 25.0 20.0 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 20.0 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 U.S. % Bond Markets E.U. % Bond Markets U.S. % Private Bond Markets E.U. % Private Bond Markets Individual Country Private Bond Markets; % of Total, 2002 - 2010 50.0 53.8 U.S. % of Private Bonds 40.0 40.0 Japan % of Private Bonds 30.0 Germany % of Private Bonds 20.0 France % of Private Bonds 10.0 8.3 3.9 0.0 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 Newly Industrialized and Emerging % of Private Bonds Bond Market Growth in Europe: Pre and Post the Euro Bond Market Growth in Europe Since the Introduction of the Euro Classifying the World’s Bond Markets The world’s bond market can be divided into two broad groups: (1) The domestic bond market is comprised of all securities issued in each country by “domestic” government entities and corporates. (1) the domestic bond market and (2) the international bond market. In this case, issuers are domiciled (i.e., headquartered) in the country where those bonds are traded. (2) The international bond market is comprised of non-residents borrowing in another country’s bond markets Furthermore, the international bond market consists of two groups: (1) Foreign Bonds and (2) Eurobonds. Domestic Versus International Bond Market by Country; % of GDP, 2009 Foreign Bonds: Characteristics Foreign Bonds are bonds issued by a non-resident and denominated in the currency of the country in which it is being placed (i.e., issued). Foreign bonds are subject to the regulations of the country in which the bond is being offered. The SEC regulates foreign bond offerings in the U.S. Historically, the most important foreign bond markets have been in Zurich, New York, and Tokyo. Example: Ford Motor Corporation issuing a yen denominated bond in Japan Zurich and Tokyo because of low market interest rates; the U.S. because of its large market. Foreign bonds are often swapped out for another currency. The Use of the Foreign Bond Market In contrast to IPO equity financing, where the majority of U.S. firms exhibit a strong home bias, in bond financing a growing number of U.S. issuers are relying more on foreign bond markets for funding. For example: The percent of all U.S. firms issuing bond’s domestically fell from 92% in 1995 to 82% in 2006. Additionally, the share of non-financial U.S. firms issuing bonds domestically declined from 95% to 83% over the same period. Thus, U.S. corporates are increasing their funding presence in the foreign bond markets. At the same time, the share of European issuers borrowing in the U.S. bond market dropped from around 20% in 2000 to approximately 9% in 2006. Thus, European firms are increasing turning to their own markets In addition to issuing more equity in their home markets for debt financing Unique Names for Foreign Bonds The financial markets have come up with unusual nicknames for foreign bonds. These include: Yankee bonds Issued in Japan. Issued in Canada. Panda bonds Issued in Australia. Maple bonds Issued in New Zealand. Kangaroo bonds Issued in the United Kingdom. Kiwi bonds Issued in the Netherlands. Samurai bonds Issued in Spain. Rembrandt bonds Bulldog bonds Issued in the United States. Matador bonds Issued in China. Kangaroo or Matilda bonds Issued in Australia. Eurobonds Eurobonds are bonds issued by a non-resident and denominated in other than the currency of the country in which it is being placed. The bond’s currency of denomination is referred to as an offshore currency. Example: Coca Cola issuing a U.S. dollar denominated bond in Europe. They are generally issued and sold simultaneously in more than one market and thus the advantage of the Eurobond market is that issuers can raise large sums of capital from investors all around the world. Issuers include national governments, supranational organizations (such as the World Bank),“AAA” corporations and global banks. The U.S. dollar is the dominant currency of denomination for Eurobonds. History of the Eurobond Market The first Eurobond (which was also a U.S. dollar denominated bond) was the July 1963 issue by the Italian Autostrade (Italian National Highway Authority), led by SG Warburg & Co and issued in London. $15 million; 5.5% coupon; 15 year bonds; listed on the London and Luxembourg stock exchanges. By 1972, the market had grown to $5 billion; $42 billion by 1982 and $371 billion by 1995. In the early 1960s, the Eurobond market was mainly a Eurodollar bond market. Today, the Eurobond market comprises bonds denominated in all the major currencies and several minor currencies. For example, in 1996, the Eurobond market included issues denominated in the Egyptian pound, Polish zloty and Croatian kuna. The Main Features of a Eurobond Eurobonds are not regulated by the country of the currency in which they are denominated. Eurobonds are “bearer bonds”, i.e., they are not registered anywhere centrally, so whomever holds (or bears) the bond is considered the owner. Bearer status also enables Eurobonds to be held anonymously. The Eurobond market is largely a wholesale (i.e., institutional market) with bonds held by large institutions. Pension funds, insurance companies, mutual funds Since they are denominated in an offshore currency, investors in euro-bonds assume both credit and foreign exchange risks (if the currency if denomination is other than their home currency). Some publically offered eurobonds trade on stock exchanges, normally in London or Luxembourg. Others are placed directly with institutional investors without a listing (private placement). Rise of the Euro-Bond Market The Eurobond market offers several advantages for borrowers that may account for its rising popularity. (1) It gives U.S. borrowers access to a wider range of lenders, enabling them to diversify their sources of long-term funding. (2) The market provides a good environment for internationally active companies to hedge foreign currency exposures (through offsetting liabilities) (3) finally, through this market companies can enhance their global profile. Nicknames for Eurobonds Dragons: U.S. dollar denominated bonds issued in Asia. Shogun: Foreign currency bonds (including U.S. dollar bonds) issued in Japan Dim-Sum: Chinese yuan denominated bond issued in Hong Kong. Equity Markets For most of the post WW II years, U.S. equity markets had routinely attracted the lion’s share of global equity activity, especially from markets that were themselves considered relatively important (size, liquidity, regulation). However, following the dramatic evolution in globalization since the early 1990s, an increasing number of alternative financial centers have developed and achieve the level of sophistication needed to attract global equity business. Early History of Equity Markets In 1899, London was the world’s leading financial center, with an estimated 30% of the global stock market. The U.S. ranked second with just under 20% but was gaining momentum. Other European countries held significant market caps, namely France and Germany with 14% and 7%, respectively. (Note only 18 countries had “major” stock markets in 1899). By 1970, the U.S. equity markets accounted for 2/3rds of the world’s total equity market. Rise of Foreign Stock Markets In 1985, the market value of foreign stock markets combined exceeded the market value of the U.S. stock market. By 2005, the U.S. share had fallen to 40%, and currently it is approximately 31% Over this time we have seen an unparalleled rise in stock markets around the world. Today, almost every country possess a stock market, and some with multiple markets. For example: Today India has 23 stock exchanges, trading over 12,000 companies (Sept, 2011). Trends in Global Equity Markets, 2002- 2010 50.0 45.0 U.S. % World Equity Market % of Total 40.0 35.0 Japan % World Equity Market 30.0 U.K. % World Equity Market 25.0 Canada % World Equity Market 20.0 Germany % World Equity Market 15.0 France % World Equity Market 10.0 Rest of the World % World Equity Market 5.0 0.0 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 But the U.S. Equity Market Still Dominates: Stock Market Capitalization, By Country, 2011 But at the Same Time U.S. Share of Equity Financing Has Declined Which is Represented by a Declining U.S. Share of Narrowly Defined (Public Offerings)IPOs IPOs by U.S. Companies Done Entirely Outside of the U.S. Cross Listing Equity Shares Cross listing refers to the listing of a company's common shares on a different exchange other than its primary and original stock exchange. In global finance, the term applies to the listing of foreign-based companies on national exchanges other than (and in addition to) its home exchange. Example of cross listings: Citigroup currently lists its stock on both the NYSE and the Tokyo Stock Exchange . Sony Corporation currently lists its shares on the Tokyo Stock Exchange, the NYSE and the London Stock Exchange. Why do Firms Cross List? • • • (1) Improved liquidity: A listing on a more-liquid stock market can potentially increase a stock's liquidity and produce larger price earnings multiples. Thus, firms with shares trading in small, less liquid markets may see price benefits from cross listing in larger secondary markets overseas; thus positive impact on value of the firm. (2) Raising capital: Having shares trade in multiple countries increases the ability of firms to raise capital. Cross listing as part of an IPO or secondary offering in the foreign market. (3) Increasing the firms visibility to potential customers, suppliers and creditors (e.g., banks and bond markets): Thus, increase sales and expand funding opportunities. (4) Information quality: A firm's willingness to cross-list its stock on a market with stringent disclosure requirements and strong investor-protection laws can provide outside investors with information they may need to determine the quality of the firm's accounting information and financial statements. (5) Investor protection: This motivation, described in academic research as "bonding," is based on the idea that registration on a US exchange acts as a mechanism that voluntarily commits the firm to a higher standard of corporate governance and investor protection. Bonding therefore might make firms attractive to risk-averse investors who might otherwise be reluctant to invest. (6) Cost of capital benefits: Cross listing may lower a company’s cost of capital through improving liquidity, better corporate governance, and providing direct access to foreign capital markets. See next slide. Impact of Cross Listing on Cost of Capital (Data: 1970 -1996) Australia Canada UK Europe Asia Before Cross Listing 13.74% 8.17% 15.56% 8.80% 16.15% After Cross Listing 12.15% 7.49% 12.91% 8.47% 14.08% Difference in Basis Points -159 -68 -265 -33 -207 Cost of Capital: Source: Andrew Karolyi, Financial Markets and Institutions, 1998. Cross Listings for Selected Exchanges Domestic and Foreign Firm Listings; Percent of Total Firms (#), March 2011 100 90 80 70 60 50 40 30 20 10 0 99 90 89 87 80 77 59 41 Domestic 23 Foreign 20 13 11 10 1 Singapore NYSE London NYSE NASDAQ Deutsche (782) Euronext (2938) Euronext (2760) Börse US (2312) Europe (756) (1132) Tokyo (2293) History of Cross Listing Number of Companies Cross Listing: 1950s: 114 1960s: 135 1970: 255 1980: 741 1990: 1,350 2000s: 2,784 Total: 5,379* *Number represents gross listings (thus, not excluding any delistings which occurred) Source: (1950s through 1990s) Schill and Sarkisian, CrossListing Waves, 2011. World Federation of Stock Markets, Annual Reports, (2000 – 2009) Dominant host country listing site (firm listings) 1950s: U.K.: (South Africa firms) 1960s: France: (U.S. firms) 1970s: U.K.: (U.S. and Irish firms) 1980s: Japan (U.S. and U.K. firms) 1990s: U.S. (Canadian and emerging market firms) 2000s: U.S. (emerging market firms) Distribution of Cross Listings by Country of Listing: 1950 – April 2006 Country 1950s 1960s 1970s 1980s 1990s 2000s Total % of Total U.S. 5 26 42 263 703 367 1,403 39.1% U.K. 22 26 63 105 184 71 471 13.1% Luxembourg 3 5 18 8 133 118 285 7.9% France 28 24 64 38 18 194 5.4% 10 41 129 13 193 5.4% 28 55 37 14 166 4.6% 12 110 13 3 138 3.8% 22 Germany Switzerland 13 19 Japan Belgium 24 19 24 18 26 11 122 3.4% Canada 1 1 5 10 23 58 98 2.7% Total Source: Schill and Sarkisian, Cross-Listing Waves, 2011. 3,592 Distribution of Cross Listings by Home Country of Listing Firm: 1950 – April 2006 Country 1950s 1960s 1970s 1980s 1990s 2000s Total % of Total Canada 16 19 16 177 258 144 630 17.5% U.S. 49 50 80 181 101 63 524 14.6% U.K. 2 11 22 65 130 53 283 8.2% 7 55 83 71 18 234 6.5% 3 2 33 102 31 172 4.8% 2 1 67 94 164 4.6% 1 20 90 37 149 4.2% 9 10 29 7 81 2.3% 16 21 37 1.0% Japan Australia 1 India Israel 1 S. Africa 18 China 8 Total Source: Schill and Sarkisian, Cross-Listing Waves, 2011. 3,592 Distribution of Cross Listings by Industry: 1950 – April 2006 Industry 1950s 1960s 1970s 1980s 1990s 2000s Total % of Total Electronics 6 12 40 74 178 177 427 11.9% Financials 3 9 38 95 190 89 424 11.8% Mining 23 13 16 101 124 89 366 10.2% Telecom & Media 5 8 7 56 157 82 315 8.8% Consumer Goods 9 20 20 64 126 43 282 7.9% Oil & Gas 10 12 21 65 100 50 258 7.2% Total Source: Schill and Sarkisian, Cross-Listing Waves, 2011. 3,592 Cross Listing on The Tokyo Stock Exchange Last foreign company listing was Citigroup on Nov 5, 2007. 60 40 20 Number of Foreign Companies Number of U.S. Companies 2008 2006 2004 2001 1999 1997 1995 1993 1991 1989 0 1987 http://www.tse.or.jp/english/listin g/foreign/transition.html 80 1985 100 1983 Foreign company listings peaked in December 1991 at 127 (with U.S. companies at 78) By November 2011, the number of foreign companies listed had fallen to 11 (with U.S. companies at 8). 120 1981 6 companies (5 U.S. companies) listed that year. 1979 140 1977 The Tokyo Stock Exchange first permitted foreign companies to list in 1973. 1975 End of the Year Data 1973 History of Foreign Listings NYSE Foreign Company Listings: 1956 – 2008: Impact of SOX? Non-U.S. Companies % of Total Peak of 473 in 2002; 410 in 2008 Peak of 18% in 2003; 12% in 2008 50 2 0 0 Non U.S. Number of Companies 2007 4 2004 100 2001 6 1998 150 1995 8 1992 200 1989 10 1986 250 1983 12 1980 300 1977 14 1974 350 1971 16 1968 400 1965 18 1962 450 1959 20 1956 500 Foreign companies as a % of total Demutualization of Stock Exchange Since the turn of this century an increasing number of stock exchanges have become public traded, for profit, organizations Visit the following sites: Historically stock markets were private organizations. However, in February 2001, Germany’s stock exchange, the Deutsche Stock Exchange went public; In July 2001, both the London Stock Exchange and Euronext went public; On March 8, 2006, the NYSE went public. http://finance.yahoo.com/q?s=NYX&ql=0 http://finance.yahoo.com/q?s=LSE.L&ql=0 http://finance.yahoo.com/q?s=DB1.DE Implications of publically traded exchanges: Inclusion of exchanges in investor portfolios. Facilitates mergers and take-overs (hostile or friendly) of exchanges. Consolidations Among Exchanges On September 22, 2000, the Euronext Stock Exchange was formed through the merger of the national stock exchanges of France, Belgium, and the Netherlands. On April 4, 2007, the New York Stock Exchange and Euronext merged to form NYSE Euronext. On July 7, 2011, the stockholders of NYSE Euronext agreed to a merger with the Deutsche Exchange In December 2001, Euronext acquired the shares of the London International Financial Futures and Options Exchange (LIFFE), in 2002 it acquired the Portuguese Stock Exchange. Currently, Brussels is examining possible anti-trust issues and has yet to approve the merger. On November 11, 2011, the Tokyo Stock Exchange announced that they had agreed to purchase the Osaka Securities Exchange for $1.68 billion. Merger will be completed by January 2013 and combined company will be called the Japan Exchange Group. Stock Exchange Consolidations In 2006 and 2007, NASDAQ attempted hostile takeovers of the London Stock Exchange. Both takeover attempts were rejected by LSE shareholders. Why are exchanges merging? (1) cost reductions (to the exchanges themselves through economies of scale). (2) to expand global capital raising benefits (IPOs) to corporations and (3) to provide liquidity (turnover) and global outreach benefits to investors. Appendix 1 The Process of Cross Listing Shares Methods of Cross Listing Cross listing can take the form of either a direct share listing or a depository receipt program. A Depositary Receipt represents ownership of equity shares in a foreign company. These receipts are issued against ordinary shares held in custody in the issuer's home market. Depository Receipt Programs American Depository Receipt (ADR): arrangement by which foreign companies cross list on U.S. exchanges. Global Depository Receipt (GDR): arrangement by which foreign companies (including U.S. companies) cross list on foreign exchanges, other than U.S. exchanges. Depository Receipts A depositary receipt is a claim against specified number of underlying common stock shares. The DR ratio to the underlying share will vary based upon the local market share price and, in the case of an ADR, the US share price of other companies in similar industries. DRs can be listed (and traded) on a major exchanges: For example: NYSE, AMEX, NASDAQ in the U.S. and London, Luxembourg, or Singapore outside of the U.S.. DRs may also trade in the over-the-counter (OTC) markets, or be privately-placed. American Depository Receipts The first ADRs issued and traded in the U.S. occurred in 1927 when JPMorgan listed the retail U.K. company, Selfridge's. ADRs were initially seen as a means of reducing the risk associated with holding shares overseas and reducing the trading (clearing) times for American investors. Today companies from around 80 countries have ADR programs in the United States. Currently, ADR Depositary receipt volume accounts for about 15% of the U.S. equity market. American Depository Receipts American Depository Receipts (ADRs): Certificates that represent ownership of shares of foreign companies. ADRs can be listed on any U.S. exchange, such as the NYSE, the American Stock Exchange, or NASDAQ. They can also be privately placed as Rule 144A securities. ADRs trade in the United States just like shares of domestic companies, with each ADR representing some multiple of the underlying foreign shares. ADR programs are managed by commercial banks on behalf of foreign companies. In the U.S. the major depository banks (April 2009 data) are Bank of New York (1,732 programs) Citibank (322 programs) and JP Morgan (250 programs) The Price of an ADR The price of an ADR trading on a U.S. stock market corresponds to the local currency price of the foreign stock in its home market, adjusted to the ratio of the ADRs to foreign company shares. Thus, the ADR price also reflects the exchange rate between the two markets. Example: ADR ratio of 1:2 for a Japanese company (i.e., each ADR represents 2 shares of the underlying stock) This stock trades in Japanese market at 1,000 yen per share and the exchange rate is 95 yen to the dollar. Given this information, this ADR would trade in the U.S. at $21.05 or (1,000 x 2)/95 = $21.05 What Causes the Price of an ADR to Change? (1) Changes in the home currency price of the foreign company. (2) Changes in the overall stock market of the ADR country. Price risk resulting from changes in the outlook for the company. Systematic risk. (3) Changes in the exchange rate between the U.S. dollar and the currency associated with the underlying asset. Everything else equal: A strong foreign currency will increase the price of the ADR. A weak foreign currency will decrease the price of the ADR. Depository Receipt Web-Site The 3 major U.S. banks offering DR programs with their web sites are as follows: (1) JP Morgan: (2) Bank of New York http://www.adr.com/ http://www.adrbnymellon.com/ (3) Citibank http://www.citiadr.idmanagedsolutions.com/www/front_p age.idms