Document 5605888

advertisement

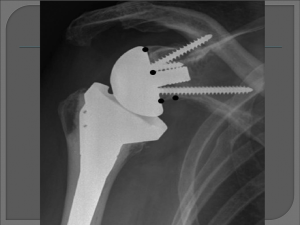

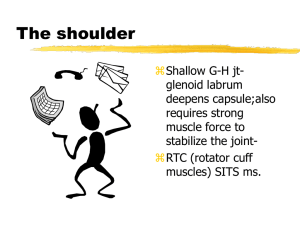

Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty (Reverse TSA) Heidi Church, SPTA Fall Internship 2012 Salt Lake Orthopaedic Clinic 1160 East 3900 South, Suite 4050 Facts • Epidemiology - in United States there are ~53,000 total shoulder arthroplasties per year compared to >900,000 total hip & total knee arthroplasties per year (9) • Indications for a Reverse TSA - ~80% of patients needing a reverse TSA have glenohumeral (GH) joint degradation and an inefficient rotator cuff, while ~18% have a good GH joint, an irreparable rotator cuff injury, and are >70 years of age. The remaining 2% have a failed TSA • 90% to 95% of patients with osteoarthritis, requiring a TSA, have their rotator cuff intact. That means 5%-10% have a deficient rotator cuff. (10) Shoulder Anatomy Glenohumeral Joint • Articular surface: inclined 130˚-150˚to the shaft of the humerus, and retroverted 20˚-30˚ (10) Anatomy of shoulder after Reverse TSA • coracoid process of scapula • acromion • humerus • prosthetic ball • prosthetic socket • scapula Biomechanics of Reverse TSA • glenoid center line “In a normal glenoid, the center line represents a line perpendicular to the articular surface of the glenoid and directed, on average, approximately 10° posterior (retroverted) to the plane of the scapula (Fig. 5A–B). The center line serves as the pillar under which the humeral head rests; glenohumeral and scapulothoracic motion are coupled to maintain the center line beneath the humeral head throughout the shoulder’s ROM. (4) In cases of severe or eccentric glenoid wear, a stable baseplate fixation can only be achieved by placing the component along the alternate glenoid center line (Fig. 5C– D). This alternate center line is defined as a line aiming at the dense bone where the scapular spine meets the body of the scapula and is not necessarily perpendicular to the remaining glenoid face.”(4) glenoid position of prosthetic head Forces on baseplate-bone junction Deltoid Muscle = axis of rotation When the axis of rotation is moved laterally, the deltoid muscle’s movement becomes one of rotation. History of TSA/Reverse TSA (3) • 1893 - first prosthetic shoulder arthroplasty - performed by French surgeon Jules Emile Péan • 1955 - proximal humeral arthroplasty used to repair fractures - Neer • 1970’s - surgeons face the challenge of developing a satisfactory prosthesis that balances joint stability and ROM. Reversed normal anatomy designs for TSA • 1972 - divergent threaded peg glenoid component - Leeds • 1973 - Single central screw - Kessel. Hydroxyapatite coated large central screw (screw thread diameter increased), center of rotation moved medially and distally - Bayley-Walker • 1973-1981 - rotator cuff and constraint in total shoulder arthroplasty - Neer designs three implants, Mark I, II, III • 1975 - emphasis on enlarged ball-and-socket to increase glenohumeral motion and increase deltoid lever arm - Fenlin • 1978 - floating fulcrum, small glenosphere articulating with larger intermediate polyethylene cup, to allow supraphysiologic motion. - Buechel • 1985-1994 - Grammont’s system introduced, four key features: 1) prosthesis must be inherently stable; 2) weightbearing part must be convex, and supported part must be concave; 3) center of sphere must be at or within glenoid neck; 4) center of rotation must be medialized and distalized. 1991 - Grammont’s second generation design changed the glenosphere from 2/3 of a sphere to 1/2 a sphere, and the baseplate included a central press-fit peg and two divergent 3.5-mm screws. 1994 - Grammont’s third variation changes directed toward the humeral component. Rehabilitation for the Reverse TSA (6) • Early Passive Motion (0-4 weeks) - wear sling to week 3, passive/selfpassive (pulley) ROM in forward flexion(FF) up to 90˚ and external rotation(ER) up to 45˚ • Active Assistive Motion (4-6 weeks) - self-passive (pulley) ROM in FF up to 120˚, ER to 45˚ • Active Motion (6-8 weeks) - active assistive ROM in FF up to 145˚ and ER up to 45˚ • Full Stretch (8-10 weeks) - full stretch in FF and ER, increase isometric muscle contraction, and add small amounts of weight, as tolerated • Strengthening (10-12 weeks) - increase weights and build deltoid muscle strength 1} 2} 4} 3} Early Passive Motion (0-4 weeks) 1}Passive manual ROM forward flexion-90˚ 2}Passive manual ROM external rotation to 45˚ 3}Self-passive, with pulley, forward flexion to 90˚ 4}Self-passive, with pulley, external rotation to 45˚ 2} 1} Active Assistive Motion (4-6 weeks) 1} Active Assistive ROM, with pulley, forward flexion to 120˚ 2} Active Assistive ROM, with pulley, external rotation to 45˚ 3} Gripping exercises 1} 3} 2} Active Motion (6-8 weeks) 1}Pulley - forward flexion, external rotation 2}Ladder - forward flexion 3}Dowel supine - forward flexion 1} 2} 4} 3} Full Stretch (8-10 weeks) 1}Internal rotation stretch with belt, horizontal/vertical 2}Supine horizontal adduction stretch 3}Ladder - forward flexion with isometric hold off ladder 4}Dowel supine - forward flexion with weight as tolerated 1} 2} 3} Strengthening (weeks 10-12) 1}Deltoid muscle strengthening - forward flexion 2}Deltoid muscle strengthening - abduction 3}Internal rotation strengthening Goals • Decrease pain • Improve range of motion • Improve strength • Improve functional ability Complications • Infection - any infection in the body can spread to the prosthesis. • incision site • deep around prosthesis • minor - treated with antibiotics • major - may require surgery and removal of prosthesis • Prosthesis problems • wear • components loosen • dislocation • Nerve injury Prognosis • SLOC case study - pain < 1/10, SPADI < 25%, percent of function 80% • Revision rates of RTSA 4.2% - 13% • Instability rate of 2.8% • RTSA for cuff tear arthropathy “results in major improvements” (7) References • 1) Acta Orthopaedica, Dec2010, Vol. 81 Issue 6, p719-726, 8p, 9 Diagrams, 1 Graph, Diagram; found on p720 • 2) Nolan B, Ankerson E, Wiater J. Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty Improves Function in Cuff Tear Arthropathy. Clinical Orthopaedics & Related Research [serial online]. September 2011;469(9):2476-2482. Available from: Academic Search Premier, Ipswich, MA. • 3) A History of Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty, Evan L. Flatow, Alicia K. Harrison, Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011 September; 469(9): 2432–2439. Published online 2011 January 7. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1733-6, PMCID: PMC3148354 • 4) How Reverse Shoulder Arthroplasty Works, Matthew Walker, Jordan Brooks, Matthew Willis, Mark Frankle, Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011 September; 469(9): 2440–2451. Published online 2011 April 12. doi: 10.1007/s11999-011-1892-0, PMCID: PMC3148368 • 5) http://jimmysmithtraining.com/six-pack-diet/good-hurt-bad-hurt • 6) Salt Lake Orthopaedic Clinic protocol for Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty • 7) Reverse Total Shoulder Arthroplasty Improves Function in Cuff Tear Arthropathy. Betsy M. Nolan, Elizabeth Ankerson, J. Michael Wiater. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2011 September; 469(9): 2476–2482. Published online 2010 November 30. doi: 10.1007/s11999-010-1683-z. PMCID: PMC3148381 • 8) http://www.umm.edu/orthopaedic/rsr.htm • 9) http://orthoinfo.aaos.org/topic.cfm?topic=A00094 • 10) Physical Therapy of the Shoulder, fourth edition, edited by Robert A. Donatelli • 11) http://my.clevelandclinic.org/services/shoulder_replacement/hic_total_shoulder_joint_replace ment.aspx