The acute abdomen

advertisement

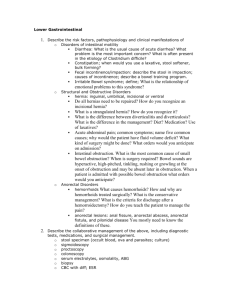

THE ACUTE ABDOMEN • Patients with an acute abdomen comprise the largest group of people presenting as a general surgical emergency. • In most acute abdominal conditions, following the history and clinical examination, plain film radiographs have traditionally been the first & most useful methods of further investigation. Plain abdominal radiographs • In most acute abdominal conditions the radiological diagnosis depends on gas patterns . • A supine abdomen and an erect chest is regarded as the basic standard radiographs. Chest X-ray This is an essential examination in any patient with acute abdomen because: 1-It is the best radiograph to show the presence of a small pneumoperitoneum. 2-A number of chest conditions may present as an acute abdominal pain : pneumonia (particularly lower lobe), MI, … . 3- Acute abdominal conditions may be complicated by chest pathology: pleural effusion frequently complicate acute pancreatitis. 4-Even when the chest radiograph is normal it acts as a valuable baseline. Small amount Abdominal radiographs – The supine abdominal radiograph is probably the single most useful film. It allows the distribution of gas and the caliber of bowel to be determined and may show displacement of bowel by soft tissue masses. – An erect abdominal radiograph is usually taken to show the air fluid levels; three or more small bowel fluid levels longer than 2.5 cm are abnormal, and indicate dilated small bowel loops with stasis. Pneumoperitoneum • In over 90% of cases the cause of pneumoperitoneum will require emergency surgery. Pseudo-Pneumoperitoneum: • These are important because failure to recognize them may lead to an unnecessary laparotomy in search for a perforated viscus. • The commonest cause for this are: Chiladiti syndrome, subdiaphragmatic fat & curvilinear pulmonary collapse . Intestinal obstruction: • Gastric dilatation : could be – Part of paralytic ileus (functional). – Mechanical : usually caused by peptic ulceration or a carcinoma of the pyloric antrum , often lead to massive fluid filled stomach which occupy most of the upper abdomen. Small bowel obstruction • The commonest cause is adhesions due to previous surgery . • The main value of plain film is in assessing the degree & severity of the obstruction (not the cause). • On plain film, changes in small bowel obstruction may appear after 3-5 hours if there is complete obstruction and marked after 12 hours. • Radiologically, complete obstruction of the small bowel usually causes small bowel dilatation with accumulation of both gas & fluid and a reduction in caliber of the large bowel, if dilated gas filled loops of small bowel will be readily identified on the supine radiograph, multiple fluid levels are present on erect film. if fluid filled loops • The dilated small bowel loops appears as a sausage, oval or round soft tissue densities that change in position in different views, sometime with small gas bubbles trapped in rows between the vulvulae conniventes on horizontal ray films; this is known as 'string of beads' sign which is virtually diagnostic of small bowel obstruction and does not occur in normal people. Gall stone ileus • This is a mechanical obstruction caused by the impaction of one or more gall stones in the intestine, usually in the terminal ileum, but rarely in the duodenum or the colon. The commonest radiological signs to be observed are : 1- A gas shadow within the bile ducts and/ or the gall bladder. 2- Complete or incomplete intestinal obstruction. 3- An abnormal location of an already observed gall stone. Large bowel obstruction • The commonest cause is carcinoma, of which about 60% are situated in the sigmoid colon. The radiological appearance of large bowel obstruction depends on the state of competence of the ileocecal valve : - TYPE 1A:the ileocecal valve is competent leading to dilated gas filled colon with its haustral markings and a distended thinwalled cecum but no distension of small bowel., this can lead to massively distended cecum, which is in then at a higher risk of perforation secondary to ischemia ( transverse cecal diameter of 9 cm had been suggested as the critical point above which the danger of perforation exists). • As this type progresses, small bowel distention occur (type 1B), with a radiological appearance identical to that of paralytic ileus . • In TYPE II obstruction, the ileocecal valve is incompetent and the cecum and ascending colon are not distended, but the back pressure from the colon extends into the small bowel which may simulate small bowel obstruction. Cecal volvulus (Right colon volvulus) • This account for less than 2% of adult intestinal obstruction ( young age group). • The diagnosis of acute cecal volvulus is rarely made on clinical ground alone, and so radiological diagnosis become much more important & it is usually comprises a distended lower abdominal viscus with one or two haustral markings, concomitant small bowel dilatation & a collapsed left half of the colon. • Note: identification of gas filled appendix confirm the diagnosis. Sigmoid volvulus • This is the classic volvulus, occurring in old, mentally subnormal patients. • It is usually chronic with intermittent acute attacks. • Radiological signs : – inverted U shaped distended loop which is devoid of haustra (ahaustral). – Liver or left flank overlap signs. – Apex of the volvulus above T10. – Air fluid ratio greater than The distinction between small & large-bowel dilatation Small bowel 1. vulvulae conniventes 2. number of loops 3. distribution of loops 4. haustra 5. diameter 6. radius of curvature 7. solid feces present in jejunum many central absent 3-5 cm small absent large bowel absent few peripheral present 5 cm + large *present haustra may be completely absent from the descending & sigmoid colon.