Epilepsy and Autism: Dr. Stefanie Berry

Epilepsy and Autism

Stefanie Jean-Baptiste Berry, MD

Pediatric Epileptologist

Northeast Regional Epilepsy Group

What is Autism?

Onset before 3 years of age

Impairment in social interaction

Impairment in communication

Restricted, repetitive and stereotyped behavior, interests and activities

Prevalence 60 in 10,000 children (0.6%)

Higher prevalence in males

High genetic and metabolic contribution

Some genetic syndromes have a high association with autism (Angelman and

Fragile X)

Autism Spectrum Disorder

Subtypes

Autistic disorder

Asperger’s syndrome

Pervasive developmental disorder

Disintegrative disorder

Rett’s syndrome

Autistic Disorder (AD)

Classic autism with incapacitating deficits in all 3 domains: 1. sociability 2. language and imagination 3. cognitive and behavior flexibility

Asperger’s syndrome

Autism without mental retardation or delayed language development

Pervasive Development Disorder

Milder autism

Disintegrative Disorder

Severe autism

Acquired between ages 2 and 10 after entirely normal early development

Regression is more profound

Rett’s Syndrome

X-linked

MeCP2 gene

Postnatal brain growth affected

Severe mental retardation and motor deficits

Clinical diagnosis

Variable causes of autism

Genetics plays a big role (high concordance in monozygotic twins, 4.5% increased risk in siblings)

Epilepsy and autism may share common neurobiological basis

? Environmental factor

Natural history and outcome of autism is variable

IQ less than 70% in most children with autism

1/3 with no communicative speech

75% who fail to show language skills by age 5 years fail to adjust personally or socially

Others make fairly adequate social adjust but retain peculiarities of personality, lack of humor and unawareness of social nuances

Even with treatment programs, only some improve significantly (2 nd half of 1 st decade)

Best outcome in patients with normal intelligence and speak before 5 years old

Applied behavior analyses (ABA) improve chances of functioning independently

What is Epilepsy?

2 or more unprovoked seizures

Incidence <10 years old 5.2 to 8.1 per

1,000 (highest <1 year)

Seizure types:

Generalized

Focal (Partial)

Focal with secondary generalization

Generalized Seizures:

1.) Generalized tonic-clonic (grand mal)-

Unconscious, whole body shaking; variable duration

2.) Absence (petit mal) – Staring, unawareness, brief (seconds)

3.) Myoclonic – Brief jerk of arm or leg

4.) Atonic – Sudden drop

Focal (Partial) Seizures:

1.) Simple – Consciousness preserved; twitching of one side of face or body, numbness, visual

2.) Complex – Impaired consciousness; twitching, head/eye deviation etc.

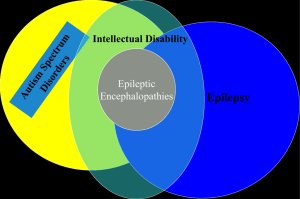

Epilepsy and Autism

Prevalence of epilepsy among all children is 2-3%

5-38% autism with epilepsy

Risk for epilepsy increased with greater intellectual disability, symptomatic vs. idiopathic, age and history of regression

35-65% with EEG abnormalities

Epilepsy in autism increased mortality

Bimodal age distribution

Peak infancy to age 5 years and adolescence

Highest risk for epilepsy in those with severe mental retardation and cerebral palsy

Epilepsy persists in the majority of patients into adult life (remission 16%)

Autistic Disorder - Clinical epilepsy by adolescence in more than 1/3 of patients

Asperger’s syndrome - Estimated 5-10% likelihood of developing epilepsy in early childhood

Pervasive Developmental Disorder - Risk for epilepsy linked to underlying brain dysfunction

Disintegrative Disorder - Risk for epilepsy as high as 70%

Rett’s Syndrome - Risk for epilepsy is more than 90%

Diagnosis complicated because seizures may be mistaken for behaviors (not responding to name)

Unusual repetitive behaviors, common in autism, hard to distinguish from seizures

All seizure types may be seen

Prevalence of epilepsy and types of seizures vary

Swedish study complex partial, atypical absence, myoclonic and tonic-clonic most common

American study tonic clonic and atypical absence most common

Other studies state complex partial with centrotemporal spikes most common

Some studies suggest that epileptiform discharges on EEG without seizures can cause behavioral and cognitive impairment

Epilepsy more common in children who regressed in language after age 3.

Usually treat based on clinical seizures not just EEG findings.

Should anti-epileptic medication be prescribed to children with autism, language regression and subclinical EEG abnormalities?

Long-duration EEGs that include slow wave sleep more likely to show epileptiform abnormalities

Long-duration EEG of children with autism spectrum disorder and regression without clinical seizures – 46% with epileptiform activity

Focal spikes - Centrotemporal spikes and temporoparietal spikes

Landau-Kleffner Syndrome

Overlap with autistic regression

Loss of language is prominent

Language regression after age 3

Acquired aphasia associated with clinical seizures or an epileptiform EEG

Clinical seizures not required for diagnosis

No decline in sociability or repetitive behaviors

EEG abnormalities (spikes, sharp waves and spike wave discharges); mainly over temporoparietal regions

25% do not have clinical seizures

Loss of language attributed to clinical or subclinical epilepsy in cortical areas responsible for language

Children with severe and persistent language disorders at increased risk for seizures and epilepsy.

Medical treatment of seizures in autism similar to treating other children with epilepsy

Limited data on response of children with epileptiform EEG without clinical seizures

Same strategy as LKS – reduce epileptiform activity

Reports that language of LKS and those with autism improved in response to anticonvulsants

Improvements have also been reported in patients treated with corticotropin, steroids, or immunoglobulins

Clinical reports of the use of Depakote in children with autism with and without clinical seizures

Most showed improvement in core symptoms of epilepsy

Absence of clinical trials, therefore no definite recommendations about treatment

Surgical resection in children with autism and intractable epilepsy – may improve seizures +/- autistic symptoms

1 study subpial transections – language and behavior improved