Deep vein thrombosis

advertisement

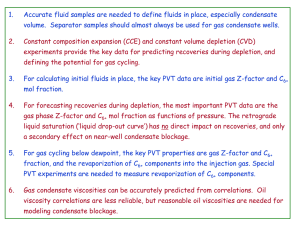

PORTAL VEIN THROMBOSIS; ANTICOAGULANT ?YES AND NO Dr. MOHAMMED EMAM Prof. tropical medicine and Hepatology ZAGAZIG UNIVERSITY 2011 CIRRHOSIS PVT in cirrhosis • has rarely been the subject of detailed evaluation and thus many questions remain unanswered regarding its clinical course, prognosis and optimal management. • Indeed, although a consensus concerning non cirrhotic extra-hepatic PVT has been published, no such consensus exists for PVT with cirrhosis. AIM OF THIS SERIES • we explore the different aspects of PVT in cirrhosis in terms of prevalence, pathogenesis, clinical course, prognosis and management. • We focus in particular on the unresolved issues, which are often the critical problems clinicians encounter in their everyday practice. • We try to provide answers to these problems on the basis of available literature. • Finally, we propose a possible research agenda to address these unresolved issues. Key points • Portal vein thrombosis (PVT) is being recognized with increasing frequency with the use of ultrasonography. • Reduced portal blood flow caused by hepatic parenchymal disease and abdominal sepsis (I .e, infectious or ascending thrombophlebitis) are the major causes Key points • PVT occurs in up to 25% of patients with advanced cirrhosis. • . There are several clinical implications of PVT, including worsening of portal hypertension, onset of refractory ascites, increased occurrence of encephalopathy, and increased complications related to organ transplantation Pathophysiology • The portal vein forms at the junction of the splenic vein and the superior mesenteric vein behind the pancreatic head. • It can become thrombosed or obstructed at any point along its course. • In cirrhosis and hepatic malignancies, the thromboses usually begin intrahepatically and spread to the extrahepatic portal vein. Pathophysiology • In most other etiologies, the thromboses usually start at the site of origin of the portal vein. Occasionally, thrombosis of the splenic vein propagates to the portal vein, most often resulting from an adjacent inflammatory process such as chronic pancreatitis The prevalence • Being 11-28%. • Operator experience or different patient and ⁄ or disease characteristics may explain these differences. • Also different means of diagnosis as angiography or surgery, influence the prevalence Etiology • Etiology of liver disease has an influence on prevalence, • 3.6% in primary sclerosing cholangitis, • 8% in primary biliary cirrhosis, • 16% in alcoholic and HBV-related cirrhosis • 35% in HCC The true prevalence • The true prevalence of PVT in cirrhosis might be greater, as intrahepatic thrombosis is more difficult to diagnose and may not be looked for unless the main portal vein shows thrombosis. • Moreover, in an autopsy study, portal vein intimal fibrosis was found in 36% of the livers examined, but most of this portal vein disease would not have been clinically detectable with available ultrasound techniques Prevalence • Amongst all cases of PVT, cirrhosis is the underlying cause in 22–28%. When HCC patients are excluded, studies based on ultrasound have reported a prevalence of 10–25%, The severity of cirrhosis • Finally, the risk of PVT is independently associated with the severity of cirrhosis. • with worsening indices of coagulation, there is more thrombosis. CAUSES& CLASSIFICATION • Portal vein thrombosis (PVT) is encountered in a variety of clinical settings such as myelo-proliferative diseases, cirrhosis, cancer or infection. • Its clinical presentation, prognosis and management vary substantially according to etiology. • It can be classified as acute or chronic, extraor intra-hepatic, occlusive or non-occlusive and progressive or self-resolving S CLINICAL PRESENTATION • Patients with these conditions may present with acute or sub acute intestinal angina. • In late stages, patients may have variceal bleeding. CLINICAL • As current imaging techniques allow detection of asymptomatic PVT during routine ultrasonographic examination, more patients with cirrhosis are diagnosed with PVT. *The presence of PVT can exclude a patient from transplant listing, or negatively impact on post transplantation survival.. Transient PVT • Transient PVT is also being recognized with increasing frequency, partly because of the great increase in the use of ultrasonography in the evaluation of patients with abdominal inflammation such as appendicitis. Hypercoagulable syndromes can lead to portomesenteric and splenic vein thrombosis. Pathophysiology • Recently, our understanding of coagulopathy in cirrhosis has changed, and cirrhosis is no longer considered to be a hypocoagulable state. • What happens is that in the setting of hepatic synthetic impairment, both pro- and anticoagulant proteins are reduced to a similar degree. • The net result is haemostatic balance that in normal circumstances is compensated, with no tendency for bleeding or thrombosis Thrombotic potential • Moreover, rather than a bleeding risk (excluding portal hypertension-related bleeding) in cirrhosis, various clinical studies as well as a recent in vitro one support a thrombotic potential. • Three recent independent studies have been published specifically evaluating the prevalence of deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) in patients with cirrhosis • the incidence of DVT or PE ranged from 0.5% to 1.87% across the different studies Thrombotic potential • even patients with cirrhosis and a prolonged PT receiving antithrombotic drugs can develop a thrombosis. • decreased hepatic synthetic function as reflected by albumin levels was associated with the risk of DVT ⁄ PE, suggesting a greater tendency to thrombosis the more severe the liver disease Thrombotic potential • The ratio of the two most powerful pro- and anti-coagulants operating in plasma, factor VIII and protein C respectively, showed a balance strongly in favour of factor VIII, which indicates hypercoagulability. • Importantly, concentrations of factor VIII, a potent pro-coagulant involved in thrombin generation, increased progressively with worsening Child-Pugh grade and score (from Child class A to C) Virchow’s triad • Thrombosis risk is substantial when • any of the components of Virchow’s triad i.e. venous stasis, endothelial injury and hypercoagulability is present. • In cirrhosis, stasis in the portal vein is favored by the relative splanchnic vasodilatation and is further aggravated by the liver architectural derangement that decreases portal flow Virchow’s triad • Moreover, a thrombophilic genotype has been reported in 69.5% of patients with cirrhosis and PVT. • high levels of factor VIII were independently associated with non cirrhotic and cirrhotic PVT • The role of anticardiolipin antibodies remains controversial. • Finally,, endotoxaemia emerged as a potential mechanism. • Thrombin generation correlated with platelet number, when thrombocytopenia was severe thrombin generation impaired. • INR in liver disease probably overestimates the bleeding risk as the international sensitivity index used is determined by means of plasma from patients on vitamin K antagonists Optimal management of portal vein thrombosis • in cirrhosis is currently not addressed in any consensus publication. • Treatment strategies most often include the use of anticoagulation, • while thrombectomy and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts are considered second-line option Intervention • The development of PVT can precipitate the need for emergency endoscopy for sclerotherapy of varices, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) creation, surgical portocaval shunt creation, transjugular or transhepatic portomesenteric thrombolysis and thrombectomy, or even resection of ischemic bowel or liver transplantation. November 15, 2011 (San Francisco, California) • A new treatment regimen with the lowmolecular-weight heparin enoxaparin reduced the incidence of portal vein thrombosis (PVT), leading to fewer events of clinical decompensation and enhanced survival in patients with advanced cirrhosis, according to data presented at The Liver Meeting 2011: American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases 62nd Annual Meeting Management • Optimal management of PVT in cirrhosis is currently not addressed in any consensus publication, including the recent practice guidelines on vascular disorders of the liver Management • Treatment strategies that are published most often include the use of anticoagulation, while thrombectomy and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunts (TIPS) are considered as secondline options. Anticoagulation • Its goal is not necessarily recanalization, but prevention of further thrombosis with extension to the superior mesenteric vein (SMV). • The recent American Association for the Study of Liver Disease (AASLD) practice guidelines on liver vascular disorders supporting anticoagulation in acute PVT, as recanalization may occur in up to 80% of cases Anticoagulation • However, anticoagulation is more complex in the setting of cirrhosis., • First anticoagulation in patients with esophageal Varices, especially when the risk of rupture risk is high, could further exacerbate a variceal bleeding should it occur. The risk to benefit • The risk to benefit ratio of anticoagulation was though to be unfavourable in cirrhosis if there are medium or large oesophageal varices. • The proportion of patients with partial or complete recanalization was significantly higher in those who received anticoagulation (8 ⁄ 19) compared with those who did not The risk to benefit • No anticoagulation-related complications were noted and no patient had to stop treatment. • Patients with complete PVT at the time of liver transplantation had significantly lower survival after transplant. This suggests that at least in patients with cirrhosis and PVT listed for liver transplantation anticoagulation should be used The risk to benefit • the use of coumarin anticoagulants increase the INR and ‘artificially’ increase the MELD score, an alternative score that excludes INR (MELDXI) has been proposed for patients on anticoagulation listed for transplantation • An attractive alternative to oral anticoagulants could be the use of lowmolecular weight heparin, the dosing of which is weight-based and screening therefore is not necessary • A second study reported complete response in 75% of patients by using enoxaparin with no serious side effects. • . It is important that enoxaparin was given for a prolonged period of 6–17 months.68 Varices&ulcers • If anticoagulation is to be used, varices should be eradicated by ligation and any ulcers healed before anticoagulation is started. Beta blocker or endoscopic? • A theoretical advantage of endoscopic therapy over nonselective beta-blockers could be argue for, as the latter might further reduce splanchnic blood flow and thus cause further portal vein stasis and thrombus extension. • Eradication of varices through ligation might be a safer choice, but iatrogenic bleeding is possible with ligation. Radiological interventions • Radiological interventions can be used in PVT to repermeate the vessel even percutaneously in acute forms through the chest wall or by using TIPS when concomitant portal hypertensive complications or cirrhosis is present • The use of TIPS is a feasible option • combined mechanical thrombectomy with intraportal thrombolysis. Therapeutic algorithm • when PVT is first diagnosed, • 1- an attempt at evaluating the time interval from • • • • appearance is made. 2- Endoscopic screening for varices takes place. 3-Anticoagulation using standard therapeutic dose is considered in all patients with acute onset of PVT and in patients with recent onset (<6 months) in whom repermeation is more likely. 4-High-risk oesophageal varices are banded before initiation of anticoagulation 5- reduction in coagulation dose is advocated when platelet count is very low Follow up • After the first 6 months of anticoagulation, even if repermeation is not accomplished, prophylactic anticoagulation is continued in patients with underlying thrombophilic conditions or in patients who are likely candidates for liver transplantation in the future, to avoid thrombosis extension in the splanchnic vessels. Longstanding PVT • When PVT is longstanding and there is cavernous transformation of the portal vein, prophylactic anticoagulation is reserved only in patients who have thrombophilic conditions and ⁄ or high risk of thrombus extension into the SMV Radiological interventions • Radiological interventions (i.e. TIPS and thrombectomy) are used in patients who have already had bleeding or intractable Ascites or when thrombosis has extended despite adequate anticoagulation Conclusions • Portal vein thrombosis in cirrhosis has many unresolved issues, which are often the critical problems clinicians encounter in their everyday practice. • We propose a possible research agenda to address these unresolved issues. Conclusions • Anticoagulant appears to be safe in most cirrhotic patients. • Thrombus extension appears to be prevented in most patients. • Recanalization can occurs in 40% of patients. • Anticoagulant should be considered in cirrhotic with PVT when portal hypertension is controlled. • Thank you Dr-MOHAMMED EMAM