Hypertensive Disorders with Pregnancy

advertisement

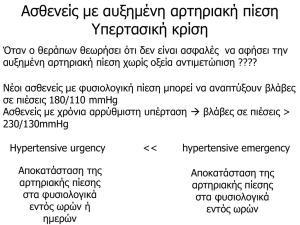

Hypertensive Disorders With Pregnancy Amr Nadim, MD Professor of Obstetrics & Gynecology Ain Shams Maternity and Women’s Hospital [prof.amrnadim@gmail.com] • C.G. is a 39 year old married white female gravida 2, para 0, with one spontaneous abortion who presented for prenatal care at 14 weeks gestation. Blood pressure at that time was 130/80. The patient had no significant medical history and her gynecologic history was significant only for oral contraceptive use several years ago. The patient noted that her physician stopped the birth control pills after only two cycles, but the patient was not told why. • The pregnancy had been unremarkable until approximately one month ago when the patient noted increased swelling of her hands and feet. A 6 Kg. weight gain in two weeks time was noted. Blood pressure at that time was 124/78. There was no urinary protein. On the day prior to admission, at 28 weeks, the patient presented with a blood pressure of 160/98 and had been sent home to bedrest with instructions to take a single baby aspirin daily. On the day following, the patient was noted at home to have a persistent blood pressure of 180/100. Avant propos… • Complicates 7-10% of pregnancies – 70% Preeclampsia-eclampsia – 30% Chronic hypertension – Eclampsia 0.05% incidence • 20% of Maternal Deaths • Cause of 10% of Preterm birth • Etiology unknown • Young female 3 fold increased risk • African American 2 fold increased risk • Multifetal pregnancies – Twins – Triplets • Hypertension • Diabetes Mellitus • Renal Disease • Collagen Vascular Disease Hypertension during Pregnancy: Classification • Pregnancy-induced hypertension – Hypertension without proteinuria/edema – Preeclampsia • mild • severe – Eclampsia • Coincidental HTN: preexisting or persistent • Pregnancy-aggravated HTN – superimposed preeclampsia – superimposed eclampsia • Transient HTN: occurs in 3rd trimester, mild Preeclampsia: Definition • Hypertension – > 140/90 – relative no longer considered diagnostic • Proteinuria – > 300 mg/24 hours or 1or 2+ on urine dipstick – may occur late • Edema (non-dependent) – so common & difficult to quantify it is rarely evoked to make or refute the diagnosis Criteria for Severe Preeclampsia • SBP > 160 mm Hg • DBP > 110 mm Hg • Proteinuria > 5 g/24 hr. or 3-4+ on dipstick • Oliguria < 500 cc/24 hr. • serum creatinine • Pulmonary edema or cyanosis • CNS symptoms (HA, vision changes) • Abdominal (RUQ) pain • Any feature of HELLP – hemolysis – liver enzymes – thrombocytopenia • IUGR or oligohydramnios Preeclampsia: Risk Factors • • • • • • • • • • Nulliparity (or, more correctly, primipaternity) Chronic renal disease Angiotensinogen gene T235 Chronic hypertension Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome Multiple gestation Family or personal history of preeclampsia Age > 40 years African-American race Diabetes mellitus Etiology and Prevention • Etiology is unknown. • Many theories: – genetic – immunologic – dietary deficiency (calcium, magnesium, zinc) • supplementation has not proven effective – placental source (ischemia) Etiology and Prevention • A major underlying defect is a relative deficiency of prostacyclin vs. thromboxane • Normally (non-preeclamptic) there is an 8-10 fold in prostacyclin with a smaller in thromboxane – prostacyclin salutatory effects dominate • vasodilation, platelet aggregation, uterine tone • In preeclampsia, thromboxane’s effects dominate – thromboxane (from platelets, placenta) – prostacyclin (from endothelium, placenta) Preeclampsia Prophylaxis: Aspirin • Aspirin has been extensively studied as a targeted therapy to thromboxane production • CLASP study, A multicenter RCT [CLASP Collaborative Group, Lancet 1994;343:619-29] – 9364 women, risk factors for PIH or IUGR or who had PIH or IUGR – 60 mg ASA daily vs. placebo – Small reduction (12%) in occurrence of PIH – Small reduction in preterm deliveries: 20 vs 22% – No difference in neonatal outcome Preeclampsia Prophylaxis: Aspirin • NIH study of high-risk patients, RCT, 60 mg aspirin daily vs. placebo [Caritis, et al., N Engl J Med 1998;338:701-5] – pre-gestational DM (471 patients) – chronic hypertension (774 patients) – multifetal gestations (688 patients) – prior history of preeclampsia (606 patients) • No reduction in development of preeclampsia in any subgroup or groups in aggregate • No difference in perinatal death, preterm delivery, IUGR, maternal or fetal hemorrhagic complications Preeclampsia: Mechanism • At this time the most widely accepted proposed mechanism for preeclampsia is: Global Endothelial Cell Dysfunction • Endothelial cell dysfunction is just one manifestation of a broader intravascular inflammatory response – present in normal pregnancy – excessive in preeclampsia – Proposed source of inflammatory stimulus: placenta Pathophysiology Of importance, and distinguishing preeclampsia from chronic or gestational hypertension, is that preeclampsia is more than hypertension; it is a systemic syndrome, and several of its “non-hypertensive” complications can be lifethreatening when blood pressure elevations are quite mild. Pathophysiology: Cardiovascular • In severe preeclampsia, typically hyperdynamic with normal-high CO, normalmod. high SVR, and normal PCWP and CVP. • Despite normal filling pressures, intravascular fluid volume is reduced (3040% in severe PIH) • Variations in presentation depending on prior treatment and severity and duration of disease • Total body water is increased (generalized edema) Pathophysiology: Cardiovascular • Preeclamptic patients are prone to develop pulmonary edema due to reduced colloid oncotic pressure (COP), which falls further postpartum: Colloid oncotic pressure: Normal pregnancy: Preeclampsia: Antepartum 22 mm Hg 18 mm Hg Postpartum 17 mm Hg 14 mm Hg Pathophysiology • Respiratory: – Airway is edematous; use smaller ET tube (6.5) – risk of pulmonary edema; 70% postpartum • Renal: – Renal blood flow & GFR are decreased – Renal failure due to plasma volume or renal artery vasospasm – Proteinuria due to glomerulopathy • glomerular capillary endothelial swelling w/subendothelial protein deposits – Renal function recovers quickly postpartum Pathophysiology: Hepatic • RUQ pain is a serious complaint – warrants imaging, especially when accompanied by liver enzymes – caused by liver swelling, periportal hemorrhage, subcapsular hematoma, hepatic rupture (30% mortality) • HELLP syndrome occurs in ~ 20% of severe preeclamptics. Pathophysiology • Coagulation: – Generally hypercoagulable with evidence of platelet activation and increased fibrinolysis – Thrombocytopenia is common, but fewer than 10% have platelet count < 100,000 – DIC may occur, • Acutely esp. with placental abruption • Neurologic: – Symptoms: headache, visual changes, seizures – Hyperreflexia is usually present – Eclamptic seizures may occur even w/out BP • Possible causes: hypertensive encephalopathy, cerebral edema, thrombosis, hemorrhage, vasospasm Hypertension during Pregnancy: Classification • Pregnancy-induced hypertension – Hypertension without proteinuria/edema – Preeclampsia • mild • severe – Eclampsia • Coincidental HTN: preexisting or persistent • Pregnancy-aggravated HTN – superimposed preeclampsia – superimposed eclampsia • Transient HTN: occurs in 3rd trimester, mild Classification • Chronic hypertension • Preeclampsia-eclampsia • Preeclampsia Superimposed upon chronic hypertension or Renal Disease • Gestational hypertension (only during pregnancy) • Transient hypertension (only after pregnancy) Chronic Hypertension Defined as hypertension diagnosed • • • Before pregnancy Before the 20th week of gestation During pregnancy and not resolved postpartum Gestational Hypertension • Gestational Hypertension: –Systolic >140 –Diastolic>90 –No Proteinurea –25% Develop Pre-eclampsia Gestational Hypertension Diagnosis of gestational hypertension: • Detected for first time after midpregnancy • No proteinuria • Only until a more specific diagnosis can be assigned postpartum If: • BP returns to normal by 12 weeks postpartum, diagnosis is transient hypertension. • BP remains high postpartum, diagnosis is chronic hypertension. • Proteinurea develops Superimposed Preeclampsia is diagnosed (25% incidence) Preeclampsia-Eclampsia • Occurs after 20th week (earlier with trophoblastic disease) • Increased BP (gestational BP elevation) with proteinuria • ‘LL’ Edema is NOT part of this definition Diagnosis of Preeclampsia-Eclampsia • Gestational Hypertension: –Systolic >140 –Diastolic>90 • Proteinuria is defined as urinary excretion – 0.3 g protein or greater in a 24-hour – +2 or greater on urine dip specimen Blood Pressure Measurement How would you measure the Blood Pressure for a pregnant lady? Preeclampsia-Eclampsia • Blood pressure • Measure blood pressure – in the sitting position, – with the cuff at the level of the heart. – Inferior vena caval compression by the gravid uterus while the patient is supine can alter readings substantially, leading to an underestimation of the blood pressure. – Blood pressures measured in the left lateral position similarly may yield falsely low values if the blood pressure is measured in the higher arm and the cuff is not maintained at heart level. • Allow women to sit quietly for 5-10 minutes before measuring the blood pressure. Blood Pressure Assessment: Patient preparation and posture Standardized technique: Patient 1. No caffeine in the preceding hour. 2. No smoking or nicotine in the preceding 15-30 minutes. 3. No use of substances containing adrenergic stimulants such as phenylephrine or pseudoephedrine (may be present in nasal decongestants or ophthalmic drops). 4. Bladder and bowel comfortable. 5. Quiet environment. Comfortable room temperature. 6. No tight clothing on arm or forearm. 7. No acute anxiety, stress or pain. 8. Patient should stay silent prior and during the procedure. Blood Pressure Assessment: Patient preparation and posture Standardized technique: Posture • The patient should be calmly seated for at least 5 minutes, with his or her back well supported and arm supported at the level of the heart. His or her feet should touch the floor and legs should not be crossed. • The patient should be instructed not to talk prior and during the procedure. Recommended Technique for Measuring Blood Pressure • Standardized technique: – Use a mercury manometer or a recently calibrated aneroid or a validated electronic device. – Aneroid devices should only be used if there is an established calibration check every 612 months. Recommended Technique for Measuring Blood Pressure • Electronic oscillometric devices: – Use a validated electronic device according to BHS, AAMI or IP standards. – For self blood pressure measurement devices, a logo on the packaging ensures that this type of device and model meets the international standards for accurate blood pressure measurement. AAMI=Association for the Advancement of Medical Instrumentation; BHS=British Hypertension Society; IP: International Protocol. Office Home / Self Recommended Technique for Measuring Blood Pressure (cont.) –Select a –cuff with the appropriate size Cuff size Arm circumference (cm) Size of Cuff (cm) From 18 to 26 9 x 18 (child) From 26 to 33 12 x 23 (standard adult model) From 33 to 41 15 x 33 (large, obese) More than 41 18 x 36 (extra large, obese) Recommended Technique for Measuring Blood Pressure (cont.) – Locate brachial and radial pulse – Position cuff at the heart level – Arm should be supported Recommended Technique for Measuring Blood Pressure (cont.) – To exclude possibility of auscultatory gap, increase cuff pressure rapidly to 20-30 mmHg above level of disappearance of radial pulse – Place stethoscope over the brachial artery Recommended Technique for Measuring Blood Pressure (cont.) – Drop pressure by 2 mmHg / sec • Appearance of sound (phase I Korotkoff) = systolic pressure – Record measurement – Drop pressure by 2 mmHg / beat • Disappearance of sound (phase V Korotkoff) = diastolic pressure – Record measurement – Take 2 blood pressure measurements, 1 minute apart Recommended Technique for Measuring Blood Pressure (cont.) Korotkoff sounds 200 180 160 No sound Clear sound Phase 1 Muffling 140 No sound Phase 2 Auscultato ry gap 120 Muffled sound Phase 3 Muffled sound Phase 4 No sound Phase 5 100 80 Systolic BP Diastolic BP 60 40 20 0 mm Hg Possible readings: 184 / 100 136 / 100 184 / 86 = correct 136 / 86 Preeclampsia-Eclampsia • Blood pressure – Record Korotkoff sounds I (the first sound) and V (the disappearance of sound) to denote the systolic blood pressure (SPB) and DPB, respectively. – In about 5% of women, an exaggerated gap exists between the fourth (muffling) and fifth (disappearance) Korotkoff sounds, with the fifth sound approaching zero. In this setting, record both the fourth and fifth sounds (eg, 120/80/40 with sound I = 120, sound IV = 80, sound V = 40). Recommended Technique for Measuring Blood Pressure Standardized technique: • For initial readings, take the blood pressure in both arms and subsequently measure it in the arm with the highest reading. • Thereafter, take two measurements on the side where BP is highest. Recommended Technique for Measuring Blood Pressure (cont.) Record the blood pressure to the closest 2 mmHg on the manometer as well as the arm used and whether the patient was supine, sitting or standing. Recommended Technique for Measuring Blood Pressure (cont.) • Avoid digit preference for five (5) or zeros (0) by not rounding up or down. • Record the heart rate. Recommended Technique for Measuring Blood Pressure (cont.) • The seated blood pressure is used to determine and monitor treatment decisions. • The standing blood pressure is used to test for postural hypotension, if present, which may modify the treatment. Blood Pressure Assessment: Patient preparation and posture Standing position For patients over age 65, diabetics and patients being treated with antihypertensives, check if there are postural changes while taking blood pressure reading, i.e. after one to five minutes in the standing position and under circumstances when the patients complains of symptoms suggestive of hypotension. Classification of PreeclampsiaEclampsia • Mild Pre-eclampsia • Severe Pre-eclampsia Classification of Preeclampsia-Eclampsia • Criteria for Severe Preeclampsia (one or more) – Blood Pressure: >160 systolic, >110 diastolic – Proteinurea: >5gm in 24 hours, over 3+ urine dip – Oligurea: less than 400ml in 24 hours – CNS: Visual changes, headache, scotomata, mental status change – Pulmonary Edema – Epigastric or RUQ Pain: Usually indicates liver involvement Classification of PreeclampsiaEclampsia • Criteria for Severe Preeclampsia (one or more) – Impaired Liver Function tests – Thrombocytopenia: <100,000 – Intrauterine Growth Restriction: With or without abnormal doppler assessment – Oligohydramnios Classification of Preeclampsia Superimposed Upon Chronic Hypertension • Hypertension and no proteinuria < 20 weeks: New-onset proteinuria after 20 weeks • Hypertension and proteinuria < 20 weeks: – Sudden increase in proteinuria – Sudden increase in BP in women whose hypertension was well controlled – Thrombocytopenia (platelet count <100,000 cells/mm3) – Increase in ALT or AST to abnormal levels Clinical Implications of Preeclampsia • Preeclampsia ranges from mild to severe. • Progression may be slow or rapid – hours to days to weeks. For clinical management, preeclampsia should be over diagnosed to prevent maternal and perinatal morbidity and mortality – primarily through timing of delivery. Symptoms of Preeclampsia • Visual disturbances typical of preeclampsia are scintillations and scotomata. These disturbances are presumed to be due to cerebral vasospasm. • Headache is of new onset and may be described as frontal, throbbing, or similar to a migraine headache. However, no classic headache of preeclampsia exists. • Epigastric pain is due to hepatic swelling and inflammation, with stretch of the liver capsule. Pain may be of sudden onset, it may be constant, and it may be moderate-to-severe in intensity. Symptoms of preeclampsia • While mild lower extremity edema is common in normal pregnancy, rapidly increasing or nondependent edema may be a signal of developing preeclampsia. However, this signal theory remains controversial and recently has been removed from most criteria for the diagnosis of preeclampsia. • Rapid weight gain is a result of edema due to capillary leak as well as renal sodium and fluid retention. Physical Findings in Preeclampsia • • • • Blood Pressure Proteinurea Retinal vasospasm or Retinal edema Right upper quadrant (RUQ) abdominal tenderness stems from liver swelling and capsular stretch Physical findings in Preeclampsia – Brisk, or hyperactive, reflexes are common during pregnancy, but clonus is a sign of neuromuscular irritability that raises concern. – Among pregnant women, 30% have some lower extremity edema as part of their normal pregnancy. However, a sudden change in dependent edema, edema in nondependent areas such as the face and hands, or rapid weight gain suggests a pathologic process and warrants further evaluation Differential Diagnosis • Documentation of HBP before conception or before gestational week 20 favors a diagnosis of chronic hypertension (essential or secondary). • HBP presenting at midpregnancy (weeks 20 to 28) may be due to early preeclampsia, transient hypertension, or unrecognized chronic hypertension. Laboratory Tests High-risk patients presenting with normal BP: • • • • Hematocrit Hemoglobin Serum uric acid If 1+ protein by routine urinalysis (clean catch) present obtain a timed collection for protein and creatinine • Accurate dating and assessment of fetal growth • Baseline sonogram at 25 to 28 weeks Laboratory Tests Patients presenting with hypertension before gestation week 20: • Same tests as described for high-risk patients presenting with normal BP • Early baseline sonography for dating and fetal size Laboratory Tests Patients presenting with hypertension after midpregnancy: • Quantification of protein excretion • Hemoglobin and hematocrit and platelet count • Serum creatinine, uric acid, and transaminase level • Serum albumin, LDH, blood smear, and coagulation profile Preeclampsia: Treatment • Goal is to prevent eclampsia and other severe complications. • Attempts to treat preeclampsia by natriuresis or by lowering BP may exacerbate pathologic changes. • Palliate maternal condition to allow fetal maturation and cervical ripening. Preeclampsia: Treatment Maternal Evaluation • Goals: – Early recognition of preeclampsia – Observe progression, both to prevent maternal complications and protect wellbeing of fetus. • Early signs: – BP rises in late second and early third trimesters. – Initial appearance of proteinuria is important. Fetal Monitoring Preeclampsia: Treatment • Maternal Evaluation…When To Hospitalize? – Often, hospitalization recommended with new-onset preeclampsia to assess maternal and fetal conditions. – Hospitalization for duration of pregnancy indicated for preterm onset of severe gestational hypertension or preeclampsia. – Ambulatory management at home or at day-care unit may be considered with mild gestational hypertension or preeclampsia remote from term Preeclampsia Indication of Delivery Preeclampsia • Antepartum Management of Preeclampsia – Little to suggest therapy alters the underlying pathophysiology of preeclampsia. – Restricted activity may be reasonable. – Sodium restriction and diuretic therapy appear to have no positive effect. Obstetric Management • Classically “stabilize and deliver” Obstetric Management • Medical management while awaiting delivery: – use of steroids X 48 hours if fetus < 34 wks – antihypertensives to maintain DBP < 105-110 – magnesium sulfate for seizure prophylaxis – monitor fluid balance, I/O, daily weights, symptoms, reflexes, HCT, plts, LFT’s, proteinuria Obstetric Management • Indications for expedited delivery: – fetal distress – BP despite aggressive Rx – worsening end-organ function – development or worsening of HELLP syndrome – development of eclampsia Antihypertensive Therapy • Most commonly, for acute control: hydralazine, labetolol • Nifedipine may be used, but unexpected hypotension may occur when given with MgSO4 • For refractory hypertension: nitroglycerin or nitroprusside may be used – Nitroprusside dose and duration should be limited to avoid fetal cyanide toxicity – Usually require invasive arterial pressure mon • Angiotensin-converting enzyme (ACE) inhibitors contraindicated due to severe adverse fetal effects Seizure Prophylaxis & Treatment • Magnesium sulfate vs. phenytoin for seizure prophylaxis in preeclampsia Lucas, et al., N Engl J Med 1995;333:201-5. – 2138 patients (75% had mild PIH) – Maternal & fetal outcomes similar except 10 seizures in the phenytoin group (0 in MgSO4) • Mg vs. diazepam & Mg vs. phenytoin for preventing recurrent seizures in eclamptics Eclampsia Trial Collaborative Group, Lancet 1995;345:1455 – Mg pts were 52% or 67% less likely to have a recurrent seizure than diazepam or phenytoin pts Seizure Prophylaxis • Evidence is strong that magnesium sulfate is indicated for – seizure treatment in eclamptics – seizure prophylaxis in severe preeclamptics • Role of magnesium prophylaxis in mild preeclamptics is less clear – awaits large, prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled trial Magnesium Sulfate • Magnesium sulfate has many effects; its mechanism in seizure control is not clear. – NMDA (N-methyl-D-aspartate) antagonist – vasodilator • Brain parenchymal vasodilation demonstrated in preeclamptics by Doppler ultrasonography – increases release of prostacyclin • Potential adverse effects: – toxicity from overdose (respiratory, cardiac) – bleeding – hypotension with hemorrhage – uterine contractility Magnesium Sulfate • Renally excreted • Preeclamptics prone to renal failure • Magnesium levels must be monitored frequently either clinically (patellar reflexes, urinary output) or by checking serum levels q 6-8 hours • • • • • Therapeutic level: Patellar reflexes lost: Respiratory depression: Respiratory paralysis: Cardiac arrest: 4-7 meq/L 8-10 meq/L 10-15 meq/L 12-15 meq/L 25-30 meq/L • Treatment of magnesium toxicity: – stop MgSO4, IV calcium, manage airway Treatment of Eclampsia • Seizures are usually short-lived. • If necessary, small doses of barbiturate or benzodiazepine (STP, 50 mg, or midazolam, 1-2 mg) and supplemental oxygen by mask. • If seizure persists or patient is not breathing, rapid sequence induction with cricoid pressure and intubation should be performed. • Patient may be extubated once she is completely awake, recovered from neuromuscular blockade, and magnesium sulfate has been administered. Anesthetic Goals of Labor Analgesia in Preeclampsia • To establish & maintain hemodynamic stability (control hypertension & avoid hypotension) • To provide excellent labor analgesia • To prevent complications of preeclampsia – intracerebral hemorrhage – renal failure – pulmonary edema – eclampsia • To be able to rapidly provide anesthesia for C/S Regional vs. General Anesthesia in Preeclampsia • Epidural anesthesia would probably be preferred by many anesthesiologists in a severely preeclamptic pt in a non-urgent setting • For urgent cases it is reassuring to know that spinal is also safe • This allows us to avoid general anesthesia with the potential for encountering a swollen, difficult airway and/or labile hypertension Regional vs. General Anesthesia in Preeclampsia • General anesthesia is a well-known hazard in obstetric anesthesia: – 16X more likely to result in anestheticrelated maternal mortality – Mostly due to airway/respiratory complications, which would only be exaggerated in preeclampsia Hawkins, Anesthesiology 1997;86:273 Platelets & Regional Anesthesia in Preeclampsia • Prior to placing regional block in a preeclamptic it is recommended to check the platelet count. • No concrete evidence at to the lowest safe platelet count for regional anesthesia in preeclampsia • Any clinical evidence of DIC would contraindicate regional anesthesia. Hazards of General Anesthesia in Preeclampsia • Airway edema is common – Mandatory to reexamine the airway soon before induction – Edema may appear or worsen at any time during the course of disease • tongue & facial, as well as laryngeal • Laryngoscopy and intubation may severe BP – Labetolol & NTG are commonly used acutely – Fentanyl (2.5 mcg/kg), alfentanil (10 mcg/kg), lidocaine may be given to blunt response Hazards of General Anesthesia in Preeclampsia • Magnesium sulfate potentiates depolarizing & non-depolarizing muscle relaxants – Pre-curarization is not indicated. – Initial dose of succinylcholine is not reduced. – Neuromuscular blockade should be monitored & reversal confirmed. Invasive Central Hemodynamic Monitoring in Preeclampsia • Usually reserved for patients with complications – oliguria unresponsive to modest fluid challenge (500 cc LR X 2) – pulmonary edema – refractory hypertension • may have increased CO or increased SVR • Poor correlation between CVP and PCWP in PIH – However, at most centers anesthesiologists would begin with CVP & follow trend • not arbitrarily hydrate to a certain number – If poor response, change to PA catheter Conclusions • Preeclampsia is a serious multi-organ system disorder of pregnancy that continues to defy our complete understanding. • It is characterized by global endothelial cell dysfunction. • The cause remains unknown. • There is no effective prophylaxis. Conclusions • Delivery is the only effective cure. • Magnesium sulfate is now proven as the best medication to prevent and treat eclampsia. • Epidural analgesia for labor pain management & regional anesthesia for C/S have many beneficial effects & are preferred. Antihypertensive Therapy • Patients with chronic hypertension should continue on their pre-pregnancy medication if NOT contraindicated with pregnancy. • The usual cut off to prescribe Antihypertensives with pregnancy is 150/100. • Care should be taken NOT to compromise the fetal circulation by bringing the blood pression down to normal. Alpha-methyl Dopa • The most commonly used and presumably the safest with pregnancy. • The usual dose starts with 250mg tds to be increased up to 2 grams per day. • It blocks the adrenaline release at post synaptic sites. Hydralazine • • • • Dose: 5-10 mg every 20 minutes Onset: 10-20 minutes Duration: 3-8 hours Side effects: headache, flushing, tachycardia, lupus like symptoms • Mechanism: peripheral vasodilator Labetalol • Dose: – IV:20mg, then 40, then 80 every 20 minutes, for a total of 220mg – Oral 100 mg bid to be increased up to 200 mg qid. ( maximum 2400mg daily) • • • • Onset: 1-2 minutes Duration: 6-16 hours Side effects: hypotension Mechanism: Alpha and Beta block Nifedipine • • • • Dose: 10 mg po, not sublingual Onset: 5-10 minutes Duration: 4-8 hours Side effects: chest pain, headache, tachycardia • Mechanism: CA channel block Clonidine • • • • Dose: 1 mg po Onset: 10-20 minutes Duration: 4-6 hours Side effects: unpredictable, avoid rapid withdrawal • Mechanism: Alpha agonist, works centrally Nitroprusside • • • • Dose: 0.2 – 0.8 mg/min IV Onset: 1-2 minutes Duration: 3-5 minutes Side effects: cyanide accumulation, hypotension • Mechanism: direct vasodilator Preeclampsia • Indications for Delivery in Preeclampsia • Maternal – Gestational age 38 weeks – Platelet count < 100,000 cells/mm3 – Progressive deterioration in liver and renal function – Suspected abruptio placentae – Persistent severe headaches, visual changes, nausea, epigastric pain, or vomiting Delivery should be based on maternal and fetal conditions as well as gestational age. Preeclampsia • Indications for Delivery in Preeclampsia • Fetal – Severe fetal growth restriction – Nonreassuring fetal testing results – Oligohydramnios Preeclampsia • The “cure” for preeclampsia is delivery – The “cure” is always beneficial for the mother, although c-section might be needed – The “cure” may be deleterious for the fetus Preeclampsia • Route of Delivery – Vaginal delivery is preferable. – Aggressive labor induction (within 24 hours). – Neuraxial (epidural, spinal, and combined spinal-epidural) techniques offer advantages. – Hydralazine, nitroglycerin, or labetalol may be used as pretreatment to reduce significant hypertension during delivery. Preeclampsia • Anticonvulsive Therapy – Indicated to prevent recurrent convulsions in women with eclampsia or to prevent convulsions in women with preeclampsia. – Parenteral magnesium sulfate reduces the frequency of eclampsia and maternal death. (Caution in renal failure.) Treatment of Acute Severe Hypertension in Pregnancy • SBP > 160 mm Hg and/or DBP > 105 mm Hg – Parenteral hydralazine is most commonly used. – Parenteral labetalol is second-line drug (avoid in women with asthma and CHF.) – Oral nifedipine used with caution. (Shortacting nifedipine is not approved by FDA for managing hypertension.) – Sodium nitroprusside may be used in rare cases. Postpartum Counseling and Followup • Counseling for Future Pregnancies • Risk of recurrent preeclampsia increases with – Preeclampsia before 30 weeks (40%) – Multiparas as compared with nulliparas or new father – Risk of recurrent preeclampsia may be substantially greater in African Americans. Remote Prognosis • Preeclampsia-Eclampsia – The more certain the diagnosis of preeclampsia, the lower the prevalence of remote cardiovascular disorders. – Preeclampsia-eclampsia in subsequent pregnancies helps define future risk. – Gestational hypertension in any pregnancy increases remote cardiovascular risk. Eclampsia • Women older than 40 years with preeclampsia have 4 times the incidence of seizures compared to women in their third decade of life. – Twenty-five percent of eclampsia cases occur before labor (ie, antepartum). – Fifty percent of eclampsia cases occur during labor (ie, intrapartum). – Twenty-five percent of eclampsia cases occur after delivery (ie, postpartum). – Patients with severe preeclampsia are at greater risk to develop seizures. – Twenty-five percent of patients with eclampsia have only mild preeclampsia prior to the seizures Causes: The cause of the seizures is not clear, although several processes have been implicated in their development. – Areas of cerebral vasospasm may be severe enough to cause focal ischemia, which may in turn lead to seizures. – Pathologic alterations in cerebral blood flow and tissue edema induced by vasospasm may result in headaches, visual disturbances, and hypertensive encephalopathy, resulting in a seizure. • Prior to the seizures, Symptoms include the following: – – – – – – Headache (82.5%) Hyperactive reflexes (80%) Marked proteinuria (52%) Generalized edema (49%) Visual disturbances (44.4%) Right upper quadrant pain or epigastric pain (19%) • Sometimes, there is: – Lack of edema (39%) – Absence of proteinuria (21%) – Normal reflexes (20%) Eclamptic seizure – The patient may have 1 or more seizures. – Seizures generally last 60-75 seconds. – The patient's face initially may become distorted, with protrusion of the eyes. – The patient may begin foaming at the mouth. – Respiration ceases for the duration of the seizure. • The seizure may be divided into 2 phases: – Phase 1 lasts 15-20 seconds and begins with facial twitching. The body becomes rigid, leading to generalized muscular contractions. – Phase 2 lasts approximately 60 seconds. It starts in the jaw, moves to the muscles of the face and eyelids, and then spreads throughout the body. The muscles begin alternating between contracting and relaxing in rapid sequence. • A coma or a period of unconsciousness follows phase 2. – Unconsciousness lasts for a variable period. – Following the coma phase, the patient may regain some consciousness. – The patient may become combative and very agitated. – The patient has no recollection of the seizure. • A period of hyperventilation occurs after the tonic-clonic seizure. This compensates for the respiratory and lactic acidosis that develops during the apneic phase. • Seizure-induced complications may include tongue biting, head trauma, broken bones, or aspiration.