New Frontiers and Treatment Paradigms for

Stroke Prevention in

Atrial Fibrillation

Evidence- and Guideline-Based Strategies for Optimizing

Clinical Outcomes and Anticoagulation-Based

Management for SPAF

Program Chairman

Samuel Z. Goldhaber, MD

Cardiovascular Division

Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Professor of Medicine

Harvard Medical School

Welcome and Program Overview

CME-certified symposium jointly

sponsored by the University of

Massachusetts Medical School and

CMEducation Resources, LLC

Commercial Support: This National

Initiative is Sponsored by an

Independent Educational Grant

from the Bristol-Myers

Squibb/Pfizer Cardiovascular

Partnership.

Program Faculty

PROGRAM CHAIRMAN

SAMUEL Z. GOLDHABER, MD

Cardiovascular Division

Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Professor of Medicine

Harvard Medical School

CHRISTIAN T. RUFF, MD, MPH

TIMI Study Group

Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Harvard Medical School

Boston, MA

ELAINE M. HYLEK, MD, MPH

Professor of Medicine

Department of Medicine

Boston University Medical Center

Boston, Massachusetts

Conflict of Interest Disclosures

Program Chairman

SAMUEL Z. GOLDHABER, MD

Research Support: Eisai, EKOS, Johnson & Johnson, sanofi-aventis

Consultant: Baxter, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi,

Eisai, Janssen, Merck, Pfizer, Portola, sanofi-aventis

CHRISTIAN T. RUFF, MD, MPH

Research Support: Daiichi Sankyo, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Meyers Squibb,

sanofi-aventis

Consultant: Alere and Beckman Coulter

ELAINE M. HYLEK, MD, MPH

Research Support: Bristol-Myers Squibb, Ortho-McNeil

Consultant: Bayer, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers Squibb, Daiichi

Sankyo, Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer

New Paradigms in the Science and Medicine of

Stroke Prevention for Atrial Fibrillation

Epidemiology and Overview

Risk, Disease Burden, and Deciphering the Maze

of Risk-Specific Interventions for AF

Focus on Non-Monitored Oral Anticoagulation and the Unmet

Need for Safer and More Effective Stroke Prevention in NVAF

Samuel Z. Goldhaber, MD

Program Chairman

Director, VTE Research Group

Cardiovascular Division

Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Professor of Medicine

Harvard Medical School

Faculty COI Disclosures

Research Support

Eisai, EKOS, Johnson & Johnson, sanofiaventis

Consultant

Baxter, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers

Squibb, Daiichi, Eisai, Janssen, Merck,

Pfizer, Portola, sanofi-aventis

Formal Definition: Atrial Fibrillation

AF is an arrhythmia characterized by

uncoordinated atrial activation, with

consequent deterioration of atrial

mechanical function

Circulation 2011; 121: e269-e367

The ECG of Atrial Fibrillation

Normal

sinus

rhythm

Atrial

fibrillation

The “3 Ps” and Natural History

of Atrial Fibrillation

Paroxysmal

Persistent

Permanent

Self-Terminating

Lasts > 7 Days

Cardioversion

Failed or Not

Attempted

Normal Sinus Rhythm

Atrial Fibrillation

Paroxysmal AF is as likely

to cause stroke as

persistent or permanent AF

Atrial Fibrillation: Epidemiology

► The No. 1 preventable cause of stroke

► In the United States, up to 16 million

individuals will be affected by the year 2050

► Increasing survival from heart attack and

increasing age (“the ‘graying’ of America”)

help explain rise in incidence of AF

Atrial Fibrillation Risk Factors

Magnani JW et al. Circulation 2011; 124: 1982-1993

Projected Number of People with AF

(millions)

Atrial Fibrillation: An Epidemic

18

16

14

US

Prevalence

16 million

12

1 in 4 lifetime

risk in men and women ≥ 40 years old

10

8

6

4

2

0

Miyakasa Y, et al. Circulation. 2006; 114:119-125.

Year

Prevalence, percent

Relationship Between

Atrial Fibrillation and Age

Age, years

Go AS, et al. JAMA. 2001; 285:2370-2375.

Atrial Fibrillation Causes Stroke

Left Atrial Appendage Thrombus

Chimowitz. Stroke 1993; 24: 1015

Zabalgoitia. J Am Coll Cardiol 1998; 31: 1622

Stroke and Atrial Fibrillation Burden

Approximately 5-fold increased risk of stroke

Quantify stroke risk: CHADS2/ CHA2DS2-VASc

AF strokes have worse outcomes

Costly health care ~ $16 billion/year

30

Framingham

20

AF prevalence

10

Strokes attributable

to AF

%

0

50–59

60–69

70–79

Age Range (years)

Wolf PA, et al. Stroke 1991; 22: 983-988

80–89

Ischemic Strokes in Atrial Fibrillation

More Likely to be Severely Disabling

Framingham Heart Study

73

58

36

33

16

Lin HJ, et al. Stroke. 1996;27:1760-1764.

30

16

11

AF PIE:

FUTURE

AF PIE:

PAST

Fuster V. Circulation 2012; epubl April 18

ESC 2012 AF Update Guidelines

Assess stroke risk exclusively with CHA2DS2VASc and no longer use CHADS2

ESC Guidelines recommend anticoagulation

for stroke prevention with CHA2DS2-VASc

score of 1 or greater

Preference given to novel, non-monitored

anticoagulants: apixaban, rivaroxaban, and

dabigatran

Anticoagulation in Atrial Fibrillation

Effects on Stroke Risk Reduction

Warfarin better

Control better

AFASAK

RRR of stroke:

62%

SPAF

BAATAF

CAFA

SPINAF

RRR All-cause mortality:

26%

EAFT

Aggregate

100%

50%

RRR, relative risk reduction.

Hart RG, et al. Ann Intern Med. 1999;131:492-501.

0

-50%

-100%

ESC 2012 Update Guidelines

HAS-BLED for Evaluation of Bleeding Risk

Clinical Characteristic

Hypertension (systolic BP > 160 mm Hg)

Abnormal renal or liver function

Points

1

1+1

Stroke

1

Bleeding

1

Labile INRs

1

Elderly (age > 65 years)

1

Drugs or alcohol

1+1

Maximum score

9

Pisters R, et al. Chest. 2010;138:1093-1100.

Swedish AF Cohort; Circulation 2011; 125: 2298-2307

Known Problems With Warfarin

1) Delayed onset/offset

2) Unpredictable dose response

3) Narrow therapeutic index

4) Drug-drug, drug-food interactions

5) Problematic monitoring

6) High bleeding rate

7) Slow reversibility

Warfarin Will Likely Survive: Why?

1)

Established efficacy

2)

Low cost ($4/month; $10/3 mos)

3)

Long track record (1954)

4)

Centralized anticoagulation clinics that maintain

TTRs > 60%

5)

Rapid, turnaround genetic testing

6)

Point-of-care self-testing

7)

INR testing q 12 weeks if stable

CoumaGen-II. Circ 2012; March 19

ACCP Chest Guidelines 2012

COUMAGEN-II

Pharmacogenetic Dosing Achieves TTR of 71%

Circulation 2012; epub March 19

Comparison Overview of New

Anticoagulants with Warfarin

Features

Warfarin

New Agents

Onset

Slow

Rapid

Dosing

Variable

Fixed

Yes

No

Many

Few

Yes

No

Half-life

Long

Short

Antidote

Yes

No

Food effect

Drug interactions

Monitoring

Sites of Action in Coagulation System

Novel Factor Xa and DT Inhibitors

Steps in Coagulation

Pathway

Drugs

TF/VIIa

Initiation

X

IX

VIIIa

IXa

Va

Propagation

II

Rivaroxaban

Apixaban

Edoxaban

Betrixaban

IIa

Dabigatran

Xa

Fibrin formation

Fibrinogen

Hankey GJ and Eikelboom JW. Circulation 2011;123:1436-1450

Fibrin

Novel Oral Anticoagulants

Important Comparative Features

Dabigatran

Rivaroxaban

• Oral direct thrombin inhibitor

• Twice daily dosing

• Renal clearance

• Direct factor Xa inhibitor

• Once daily (maintenance), twice daily (loading)

• Renal clearance

Apixaban

• Direct factor Xa inhibitor

• Twice daily dosing

• Hepatic clearance

Edoxaban

• Direct factor Xa inhibitor

• Once daily dosing

• Hepatic clearance

Circulation 2010;121:1523

Comparison of Phase 3 SPAF Trials

for NOACs: A Robust Trial Base

Novel Anticoagulants

Fxa Inhibitor

FIIa Inhibitor

Dabigatran

Rivaroxaban

Apixaban

Edoxaban

Open Label

Double Blind

Double Blind

Double Blind

Two Doses

Two Doses

Two Doses

Two Doses

Twice Daily

Once Daily

Twice Daily

Once Daily

RE-LY

ROCKET-AF

ARISTOTLE

ENGAGE

“Best Options” for Anticoagulation

The Consensus is Shifting

Despite continued use of warfarin, NOACs are

considered by many professional medical

organizations to be the “best option” for

anticoagulation of SPAF patients:

►

ESC 2012 AF Update Guidelines

►

ACCP 2012 Guidelines

►

Canadian AF Guidelines

ESC 2012

UPDATE

GUIDELINES

For

ATRIAL

FIBRILLATION

The Rationale for AF Registries

Registries provide a “real life” perspective on patient

populations, management “in the field,” and

outcomes in settings that do not have the special

resources and monitoring capabilities of pivotal

randomized clinical trials.

Information from registries complements clinical trial

data.

Registries can highlight the disconnect between

evidence/guidelines and clinical practice.

The GARFIELD Registry

►

Novel approach to outcomes research

►

Planned to be conducted in 50 countries

►

50,000 prospective and 5000 retrospective patients

►

Patients newly diagnosed with non-valvular AF

►

Five sequential cohorts

►

Random site selection

►

Sites representative of national AF care settings

►

Consecutive patients

►

Minimum follow-up period of 2 years

Summary of Garfield Data

Cohort One: ESC 2012

►

10,537 were available for this analysis

• 5075 retrospective and 5462 prospective

►

Newly diagnosed patients carry high risk for stroke

●

●

►

57% with CHADS2 score >2

83% with CHA2DS2-VASc score >2

VKAs not prescribed in:

●

●

38% of patients with CHADS2 score >2

40% of patients with CHA2DS2-VASc score >2

Modest Use of Vitamin K Antagonists

Even in High-Risk Patients

European Heart Survey

OAC therapy (%)

100

5333 AF patients in 35 countries: 2003–2004

80

60

58

59

1

2

64

61

3

4

40

20

0

CHADS2 score

OAC, oral anticoagulant

Nieuwlaat et al. Eur Heart J 2006; Gage et al. JAMA 2001

A “Failure to Prophylax” Syndrome

Over the past decade, about 40% of patients

with atrial fibrillation are unprotected from

stroke because of failure to prescribe

anticoagulation.

Because criteria for anticoagulation have

expanded in 2012, the problem has intensified.

Heightened awareness of the disconnect

between guidelines/evidence and suboptimal

intervention for SPAF. Anticoagulation is

necessary as a first step.

The SPAF Landscape 2012: Conclusions

► The frequency of atrial fibrillation is increasing,

so risk of devastating stroke is increasing as

well.

► Anticoagulants can effectively reduce stroke

risk, but they are underutilized.

► NOACs have less ICH bleeding risk than

warfarin and are superior—or at least

noninferior—for stroke prevention.

► We must overcome the failure-to-prophylax

syndrome.

New Paradigms in the

Science and Medicine of Heart Disease

State-of-the-Art Risk Stratification of

Patients with Atrial Fibrillation

Anticoagulation Strategies Based on Established and

Evolving Atrial Fibrillation Scoring Systems for

Thrombosis and Hemorrhagic Risk

Elaine M. Hylek, MD, MPH

Professor of Medicine

Department of Medicine

Boston University Medical Center

Boston, Massachusetts

Independent Predictors of Stroke in AF

Systematic Review

Significant by

Multivariate Analysis

Adjusted Relative Risk

(95% CI)

Prior stroke or TIA

5 of 5 studies

2.5 (1.8–3.5)

Increasing age

6 of 6 studies

1.5/decade (1.3–1.7)

History of hypertension or

systolic BP > 160 mm Hg

5 of 5 studies

2.0 (1.6–2.5)

Diabetes

4 of 4 studies

1.8 (1.5–22)

Female gender

3 of 6 studies

1.6 (1.4–1.9)

Heart failure

0 of 4 studies*

Not significant

Coronary artery disease

0 of 4 studies

Not significant

* Significant in a subgroup of participants undergoing echocardiography in

trials included AFI pooled analysis

Hart RG et al. Neurology 2007; 69: 546.

Nonvalvular Atrial Fibrillation

Stroke Rates Without Anticoagulation

According to Isolated Risk Factors

Prior

Hypertension

Age

Stroke/TIA > 75 years

Hart RG et al. Neurology 2007; 69: 546.

Female

Diabetes Heart Failure

LVEF

Risk Stratification in Atrial Fibrillation

Established Stroke Risk Factors

High-Risk Factors

Moderate-Risk Factors

► Mitral stenosis

►Age > 75 years

►Hypertension

►Diabetes mellitus

►Heart failure or ↓ LV function

► Prosthetic heart valve

► History of stroke or TIA

Less Validated Risk Factors

►

►

►

►

Age 65–75 years

Coronary artery disease

Female gender

Thyrotoxicosis

Singer DE, et al. Chest 2004;126:429S.

Fang MC, et al. Circulation 2005; 112: 1687.

The CHADS2 Score

Stroke Risk Threshold Favoring Anticoagulation

Approximate

Risk Threshold for

Anticoagulation

Score

(points)

Risk of Stroke

(%/year)

0

1.9

1

2.8

3%/year

2

3

4

5

6

Van Walraven C, et al. Arch Intern Med 2003; 163:936.

Go A, et al. JAMA 2003; 290: 2685.

Gage BF, et al. Circulation 2004; 110: 2287.

4.0

5.9

8.5

12.5

18.2

The CHADS2 Score

Stroke Risk Score for Atrial Fibrillation

Score (points)

Prevalence (%)*

Congestive Heart failure

Hypertension

Age > 75 years

Diabetes mellitus

Stroke or TIA

1

1

1

1

2

32

65

28

18

10

Moderate-High risk

Low risk

>2

0-1

50-60

40-50

VanWalraven C, et al. Arch Intern Med 2003; 163:936.

* Nieuwlaat R, et al. (EuroHeart survey) Eur Heart J 2006 (E-published).

CV Event Rates in Patients with Atrial

Fibrillation Related to CHADS2 Score

REACH Registry

Goto S, et al. Am Heart J 2008; 156: 855.

The CHA2DS2-VASc Score

Stroke Risk Score for Atrial Fibrillation

Weight (points)

Congestive heart failure or LVEF < 35%

Hypertension

Age > 75 years

Diabetes mellitus

Stroke/TIA/systemic embolism

Vascular Disease (MI/PAD/Aortic plaque)

Age 65-74 years

Sex category (female)

1

1

2

1

2

1

1

1

Moderate-High risk

Low risk

>2

0-1

Lip GYH, Halperin JL. Am J Med 2010; 123: 484.

Patient Selection for Anticoagulation

Additional Considerations

► Risk of bleeding

► Newly anticoagulated vs established therapy

► Availability of high-quality anticoagulation

management program

► Patient preferences

Published Bleeding Risk Scores

Patients on Oral Vitamin K Antagonist Anticoagulant

Therapy

Low

Kuijer et al.

Arch Intern Med

1999;159:457.

0

Moderate High

1-3

>3

Beyth et al.

Am J Med

1998;105:91.

0

1-2

≥3

Gage et al.

Am Heart J

2006;151:713.

<1

2-3

≥4

Shireman et al.

Chest

2006;130:1390.

≤

1.07

1.07 - 2.19

>

2.19

Tay, Lane & Lip. Thromb Haemost 2008; 100: 955.

1.6 x age + 1.3 x sex +2.2 x cancer; 1 point for

≥ 60 years old, female or malignancy; 0 if none

≥ 65 years old; GI bleed within 2 weeks; prior

stroke; comorbidities (recent MI, Hct < 30%,

diabetes, Cr > 1.5 mg/dL) ;1 point for each

condition; 0 if absent

HEMORR2HAGES score: liver/renal disease,

EtOH abuse, malignancy, > 75 years old, low

platelet count or function, rebleeding risk,

uncontrolled Htn, anemia, genetic factors

(CYP2C9) risk of fall or stroke; 1 point for each

factor; 2 points for previous bleeding

(0.49 x age > 70) + (0.32 x female) + (0.58 x

remote bleed) + 0.62 x recent bleed) + 0.71 x

EtOH/drug abuse) + (0.27 x diabetes) + (0.86 x

anemia) + (0.32 x antiplatelet drug use); 1 point

for each; 0 if none

Advances in the

Science and Medicine of SPAF

Importance of the HAS-BLED Score

Risk Score for Predicting Bleeding in

Anticoagulated Patients with Atrial Fibrillation

Weight (points)

Hypertension (> 160 mm Hg systolic)

Abnormal renal or hepatic function

Stroke

Bleeding history or anemia

Labile INR (TTR < 60%)

Elderly (age > 75 years)

Drugs (antiplatelet, NSAID) or alcohol

1

1-2

1

1

1

1

1-2

High risk

Moderate risk

Low risk

>4

2-3

0-1

(> 4%/year)

(2-4%/year)

(< 2%.year)

Pisters R, et al. Chest 2010; 138: 1093.

Lip GYH, et al. J Am Coll Cardiol 2010; 57: 173.

Canadian Cardiovascular Society

AF Guidelines 2012 Update

Assess Thromboembolic

Risk (CHADS2)

CHADS2 = 1

CHADS2 = 0

CHADS2 > 2

Increasing stroke risk

No antithrombotic

No additional

risk factors of

stroke

ASA

Either female

sex or

vascular

disease

OAC*

Age > 65 y or

combination

of female sex

and vascular

disease

OAC*

*Aspirin is a reasonable

alternative in some as

indicated by risk/benefit

OAC

Canadian Cardiovascular Society

AF Guidelines 2012 Update

All patients with atrial fibrillation or atrial flutter

(paroxysmal, persistent, or permanent), should be

stratified using a predictive index for stroke (eg, CHADS2)

and for the risk of bleeding (eg, HAS-BLED), and that

most patients should receive either an oral anticoagulant

or aspirin. (Strong recommendation, high quality

evidence)

When oral anticoagulation therapy is indicated, most

patients should receive dabigatran, rivaroxaban, or

apixaban* in preference to warfarin.

(Conditional recommendation. high-quality evidence).

*Once approved by Health Canada.

ESC 2012 AF Update Guidelines

2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: Europace. 2012 Aug 24

ESC 2012 Guidelines: Identifying

“Truly Low-Risk” Patients with AF

Thus, this guideline strongly recommends a practice shift toward

greater focus on identification of ‘truly low-risk’ patients with AF

(ie,‘age <65 and lone FL’ who do not need any antithrombotic

therapy), instead of trying to focus on identifying ‘high-risk’

patients.

To achieve this, it is necessary to be more inclusive (rather than

exclusive) of common stroke risk factors as part of any

comprehensive stroke risk assessment. Indeed, patients with AF

who have stroke risk factor(s) > 1 are recommended to receive

effective stroke prevention therapy, which is essentially OAC with

either well-controlled VKA therapy [INR 2-3, with a high

percentage of time in the therapeutic range (TTR), for example,

at least 70%] or one of the NOACs

2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: Europace. 2012 Aug 24

CHA2DS2-VASc vs. CHADS2

Is More Information Better?

►

►

►

►

The new scoring systems have been adopted in

Europe but not in the United States, even in the

latest practice guideline updates.

The components of the CHA2DS2-VASc score are

less well validated than those of the CHADS2 score.

The C-statistic used to validate the CHA2DS2-VASc

score is only marginally superior to those of other

schema.

There is no consensus about how to combine

stroke risk and bleeding risk scores into a

composite instrument.

Current AF Stroke Risk Stratification Schemes

Limitations, Challenges, and Opportunities

►

All have modest predictive value for thromboembolism

Patients classified as low risk must truly be at low risk to safely avoid

anticoagulation

Should classify small proportion into the intermediate risk category, for

which optimum therapy is less clear

►

Incorporate risk factors as cumulative

►

Should be comprehensive yet easy to apply

►

Scoring systems are the most popular method

Acronym for easy recall

Should be validated in multiple populations, ideally clinical practice

populations, rather than in the control arms of trial cohorts

Risk schemes must evolve to address the

wider therapeutic margin offered by new oral anticoagulants

Lip GYH, Halperin JL. Am J Med 2010;123:484

Atrial Fibrillation and Thromboembolism

The Next Challenges

►

►

►

►

►

Better risk-stratification that balances stroke and

bleeding and addresses new anticoagulants

Noninvasive methods to better predict events and

guide therapy

Safer treatments for the highest risk patients

Achieving and confirming successful rhythm

control over time

Targeted atrial fibrillation prevention

New Paradigms in the

Science and Medicine of Heart Disease

Deciphering the Maze of Evidence from

Landmark Trials Evaluating Non-Monitored,

Oral Anticoagulants (NOACs) for SPAF

Christian T. Ruff, MD, MPH

TIMI Study Group

Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Harvard Medical School

Boston, MA

Faculty COI Disclosures

Research Support

Daiichi Sankyo, AstraZeneca, Bristol-Meyers

Squibb, sanofi-aventis

Consultant

Alere and Beckman Coulter

Properties of an Ideal Anticoagulant

Properties

Benefit

Oral, once-daily dosing

Ease of administration

Rapid onset of action

No need for overlapping

parenteral anticoagulant

Minimal food or drug interactions

Simplified dosing

Predictable anticoagulant effect

No coagulation monitoring

Extra renal clearance

Safe in patients with renal

disease

Rapid offset in action

Simplifies management in case of

bleeding or intervention

Antidote

For emergencies

Major Advances In

Oral Anticoagulation for SPAF

ROCKET AF

(Rivaroxaban)

2010

6 Trials of Warfarin vs Placebo

1989-1993

RE-LY

(Dabigatran)

2009

ENGAGE AF

(Edoxaban)

2013

ARISTOTLE

(Apixaban)

2011

Comparative Pharmacokinetics/

Pharmacodynamics of Novel Agents

Dabigatran

Apixaban

Rivaroxaban

Edoxaban

IIa

(thrombin)

Xa

Xa

Xa

2

1-3

2-4

1-2

None

15%

32%

NR

Bioavailability

7%

66%

80%

> 45%

Transporters

P-gp

P-gp

P-gp/BCRP

P-gp

Protein binding

35%

87%

>90%

55%

12-14h

8-15h

9-13h

8-10h

Renal elimination

80%

25%

33%

35%

Linear PK

Yes

Yes

No

Yes

Target

Hrs to Cmax

CYP metabolism

Half-life

BCRP = breast cancer resistance protein; CYP = cytochrome P450; NR = not reported;

P-gp = P-glycoprotein

Ruff CR and Giugliano RP. Hot Topics in Cardiology 2010;4:7-14

Ericksson BI, et al. Clin Pharmacokinet 2009;48:1-22

The RE-LY Trial: Dabigatran

RE-LY

Atrial fibrillation

≥1 Risk Factor

Absence of contra-indications

951 centers in 44 countries

PROBE=Prospective Randomized

Open Trial with Blinded

Adjudication of Events

R

open

Warfarin

(INR 2.0-3.0)

N = 6022

Blinded

Dabigatran

Etexilate

110 mg bid

N = 6015

Dabigatran

Etexilate

150 mg bid

N = 6076

10 efficacy outcome = stroke or systemic embolism

10 safety outcome = major bleeding

Non-inferiority margin 1.46

RE-LY Efficacy (Dabigatran)

Stroke/Systemic Embolic Event

Non-inferiority Superiority

P-value

P-value

Dabigatran 110 vs Warfarin

< 0.001

Dabigatran 150 vs Warfarin

< 0.001

0.34

< 0.001

Margin = 1.46

Connolly, et al. N Engl J

Med 2009;361:1139-51

0.50

0.75

HR

1.00

1.25

(95% CI)

1.50

RE-LY Efficacy (Dabigatran)

Dabigatran 110 mg

Dabigatran 150 mg

Stroke/SEE

0.91 (0.74-1.11)

0.66 (0.53-0.82)

Ischemic Stroke

1.11 (0.89-1.40)

0.76 (0.60-0.98)

Hemorrhagic Stroke

0.31 (0.17-0.56)

0.26 (0.14-0.49)

Connolly, et al. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1139-51

0.1

0.3

0.5

Dabigatran Better

1.0

2.0

Warfarin Better

RE-LY Safety Results (Dabigatran)

Dabigatran 110 mg

Dabigatran 150 mg

Major Bleed

ICH

GI Bleed

MI

0.80 (0.69-0.93)

0.93 (0.81-1.07)

0.31 (0.20-0.47)

0.40 (0.27-0.60)

1.10 (0.86-1.41)

1.50 (1.19-1.89)

1.29 (0.96-1.75)

1.27 (0.94-1.71)

Connolly, et al. N Engl J Med 2009;361:1139-51

0.1

0.3

0.5

Dabigatran Better

1.0

2.0

Warfarin Better

RE-LY Efficacy Stratified by CHADS2

Annualized Rate Stroke/SEE (%)

CHADS2

D110

D150

WARF

0-1

1.06

0.65

1.05

2

1.43

0.84

1.38

3-6

2.12

1.88

2.68

D150

mg

D110

mg

P=

0.44

0.50

1.00

1.50

Dabigatran

Warfarin

better

better

Oldgren J, et al. ACC 2010

P=

0.50

1.00

Dabigatran

better

0.82

1.50

Warfarin

better

RE-LY Efficacy Stratified by

Prior Vitamin K Anatagonist

Ezekowitz MD, et al. Circulation 2010;122:2246-2253

RE-LY Cardioversion (Dabigatran)

Stroke/SEE

1.8

Major Bleeding

1.7

1.6

1.4

1.2

1

0.8

0.8

0.6

0.6

0.4

0.6

0.6

0.3

0.2

0

Dabi 110 mg

Dabi 150 mg

(N = 647)

(N = 672)

Nagarakanti R, et al. Circulation 2011;123:131-136

Warfarin

(N = 664)

Dabigatran Approval

Prevention of stroke in AF

Available in 75 mg and 150 mg

(twice daily)

Dose of 75 mg if CrCl 15-30 mL/min

Data in favor of 110 mg were

“suggestive, but not entirely

convincing”

ROCKET AF: Rivaroxaban

Risk Factors

• CHF

• Hypertension

At least 2

• Age 75

required

• Diabetes

OR

• Stroke, TIA or Systemic

embolus

Atrial Fibrillation

Rivaroxaban

20 mg daily

15 mg for Cr Cl 30-49

Randomize

Double blind / Double Dummy

(n = 14,266)

Warfarin

INR target - 2.5

(2.0-3.0 inclusive)

Monthly Monitoring and adherence to

standard of care guidelines

Primary End point: Stroke or non-CNS Systemic Embolism

Statistics: non-inferiority, > 95% power, 2.3% warfarin event rate

ROCKET AF Efficacy

Stroke/Systemic Embolic Event

Rivaroxaban Warfarin

On

Treatment

Event

Rate

Event

Rate

HR

(95% CI)

P-value

1.70

2.15

0.79

(0.65, 0.95)

0.015

2.12

2.42

0.88

(0.74, 1.03)

0.117

N = 14,143

ITT

N = 14,171

0.5

1

Rivaroxaban

better

2

Warfarin

better

Event Rates are per 100 patient-years

Based on Safety on Treatment or Intention-to-Treat through

Site Notification populations

Patel, et al. N Engl J Med 2011;365(10);883-891

ROCKET AF Key Secondary Efficacy

Rivaroxaban

(%/yr)

Warfarin

(%/yr)

Hazard Ratio

(95% CI)

Pvalue

Ischemic Stroke

1.34

1.42

0.94 (0.75-1.17)

0.581

Hemorrhagic Stroke

0.26

0.44

0.59 (0.37-0.93)

0.024

MI

0.91

1.12

0.81 (0.63-1.06)

0.121

Total Mortality

1.87

2.21

0.85 (0.70-1.02)

0.073

Vascular Mortality

1.53

1.71

0.89 (0.73-1.10)

0.289

Event

Patel, et al. N Engl J Med 2011; 365(10);883-891

ROCKET AF Safety (Rivaroxaban)

Rivaroxaban

(%/yr)

Warfarin

(%/yr)

Hazard Ratio

(95% CI)

Pvalue

Major and Clinically

Relevant Bleed

14.9

14.5

1.03 (0.96-1.11)

0.44

Major Bleed

3.6

3.4

1.04 (0.90-1.20)

0.58

Fatal Bleed

0.2

0.5

0.50 (0.31-0.79)

0.003

ICH

0.5

0.7

0.67 (0.47-0.93)

0.02

Event

Patel, et al. N Engl J Med 2011; 365(10);883-891

ROCKET AF Efficacy (Rivaroxaban)

Moderate Renal Impairment

Fox KA, et al. Eur Heart J 2011;32(19):2387-94.

ROCKET AF Safety

Moderate Renal Impairment

Fox KA, et al. Eur Heart J 2011;32(19):2387-94.

Rivaroxaban Approval

Prevention of stroke in AF

Dose 20 mg if CrCl > 50 mL/min

Dose of 15 mg if CrCl 15-50 mL/min

AVERROES

AVERROES Trial Design: Apixaban

36 countries, 522 centers

AF and >1 risk factor, and

demonstrated or unexpected

unsuitable of VKA

R

Apixaban 5 mg bid

2 mg bid in selected patients

5600 patients

Double-blind

ASA (81-324 mg/d)

Primary Outcome: Stroke or

Systemic Embolic Event (SEE)

AVERROES: Apixaban

Stroke or Systemic

Embolic Event

Major

Bleeding

0.020

0.05

0.04

Aspirin

0.03

P < 0.001

Apixaban

0.01

0.00

3

6

P < 0.001

0.010

0.02

0

Apixaban

0.015

9

12

18

HR 0.45 (0.32-0.62)

Connolly SJ, et al. N Engl J Med 2011 (epub)

Aspirin

0.005

0.000

0

3

6

9

12

HR 1.13 (0.74-1.75)

18

ARISTOTLE: Apixaban

ARISTOTLE Trial Design: Apixaban

Inclusion risk factors

Age ≥ 75 years

Prior stroke, TIA, or SE

HF or LVEF ≤ 40%

Diabetes mellitus

Hypertension

Randomize

double blind,

double dummy

(n = 18,201)

Exclusion

Mechanical prosthetic valve

Severe renal insufficiency

Need for aspirin plus

thienopyridine

Apixaban 5 mg oral twice daily

Warfarin

(2.5 mg bid in selected patients)

(target INR 2-3)

Warfarin/warfarin placebo adjusted by INR/sham INR

based on encrypted point-of-care testing device

Primary outcome: stroke or systemic embolism

Hierarchical testing: non-inferiority for primary outcome, superiority for

primary outcome, major bleeding, death

ARISTOTLE Efficacy: Apixaban

HR 0.79 (0.66–0.95)

(1.60 %/yr)

21% RRR

(1.27 %/yr )

P (non-inferiority) < 0.001

P (superiority) = 0.011

Granger CB, et al. NEJM 2011; 365:981-992

ARISTOTLE Efficacy Outcomes

Apixaban

(N = 9120)

Outcome

Stroke or systemic embolism*

Warfarin

(N = 9081)

Event

Event Rate

Rate

(%/yr)

(%/yr)

HR (95% CI)

P Value

1.27

1.60

0.79 (0.66, 0.95)

0.011

1.19

1.51

0.79 (0.65, 0.95)

0.012

Ischemic or uncertain

0.97

1.05

0.92 (0.74, 1.13)

0.42

Hemorrhagic

0.24

0.47

0.51 (0.35, 0.75)

< 0.001

0.09

0.10

0.87 (0.44, 1.75)

0.70

All-cause death*

3.52

3.94

0.89 (0.80, 0.998)

0.047

Stroke, SE, or all-cause death

4.49

5.04

0.89 (0.81, 0.98)

0.019

Myocardial infarction

0.53

0.61

0.88 (0.66, 1.17)

0.37

Stroke

Systemic embolism (SE)

Granger CB, et al. NEJM 2011; 365:981-992

ARISTOTLE Safety End Points

Apixaban

(%/yr)

Warfarin

(%/yr)

Hazard Ratio

(95% CI)

Pvalue

ISTH Major Bleeding

2.13

3.09

0.69 (0.60-0.80)

<

0.001

ICH

0.33

0.80

0.42 (0.30-0.58)

<

0.001

GUSTO Severe

0.52

1.13

0.46 (0.35-0.60)

<

0.001

Gastrointestinal

0.76

0.86

0.89 (0.70-1.15)

0.37

Event

Granger CB, et al. NEJM 2011; 365:981-992

ARISTOTLE: Apixaban

Renal Function

Major Bleeding

Annualized Event Rate

Stroke or SEE

Baseline Cockcroft-Gault eGFR mL/min

Hohnloser SH, et al. EHJ 2012 (epub August 29)

Phase III: Protocol Schema

N = 21,105

DOUBLE BLIND

DOUBLE DUMMY

Low dose regimen

Edoxaban 30 mg qd

(n ≈ 7000)

AF on Electrical

Recording < 12 mo

Intended oral A/C

CHADS2 >2

R

Randomization Stratified By

1. CHADS2 2-3 vs 4-6

2. Drug Clearance

High dose regimen

Edoxaban 60 mg qd

(n ≈ 7000)

Active Control

Warfarin

(n ≈ 7000)

Median Duration of Follow-up 24 Months

Primary Objective

Edoxaban: Therapeutically as Good as Warfarin

1º EP = Stroke or SEE (Noninferiority Boundary HR 1.38)

2º EP = Stroke or SEE or CV mortality

Safety EP’s = Major Bleeding, Hepatic Function

SEE = systemic embolic event

EVENT

DRIVEN

Ruff CR et al. Am Heart J 2010; 160:635-41

Pivotal Atrial Fibrillation Trials

Baseline Characteristics

RE-LY

(Dabigatran)

ARISTOTLE

(Apixaban)

ENGAGE AF-TIMI 48*

(Edoxaban)

ROCKET-AF

(Rivaroxaban)

# Enrolled

18,113

18,201

21,105

14,264

Age (yrs)

72 ± 9

70 [63-76]

72 [64-77]

73 [65-78]

Female

36%

35%

38%

40%

CHADS2 score ≥3

32%

30%

52%

87%

VKA naive

50%

43%

41%

38%

Paroxysmal AF

33%

15%

25%

18%

Prior stroke/TIA

20%

19%

18% / 12%

55%**

Diabetes

23%

25%

36%

40%

Prior CHF

32%

35%

56%

62%

Hypertension

79%

87%

90%

91%

*Preliminary data

**includes prior systemic embolism

Connolly SJ et al. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:1139-51

Patel MR et al. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:883-91

Granger CB et al. N Engl J89

Med 2011; 365:981-92

Ruff CR et al. Am Heart J 2010; 160:635-41

Pivotal Atrial Fibrillation Trials

Dose Comparison

Drug

N

Dose (mg)

Frequency

Initial Dose adj*

Dose adj (%)

Dose adj* after

randomization

Design

RE-LY

ROCKET-AF

ARISTOTLE

ENGAGE

AF-TIMI 48

Dabigatran

Rivaroxaban

Apixaban

Edoxaban

18,113

14,266

18,201

21,105

150, 110

bid

20

qd

5

bid

60, 30

qd

No

20 → 15 mg

5 → 2.5 mg

60 → 30 mg

30 → 15 mg

0

21

4.7

> 25

No

No

No

Yes

PROBE

2 x blind

2 x blind

2 x blind

*Dose adjusted in patients with ↓drug clearance.

PROBE = prospective, randomized,

open-label, blinded end point evaluation

Connolly SJ et al. N Engl J Med 2009; 361:1139-51

Patel MR et al. N Engl J Med 2011; 365:883-91

Granger CB et al. N Engl90

J Med 2011; 365:981-92

Ruff CR et al. Am Heart J 2010; 160:635-41

Pivotal Atrial Fibrillation Trials

Results to Date

Drug

Dose (mg)

RE-LY

ROCKET-AF

ARISTOTLE

Dabigatran

110 bid 150 BID

Rivaroxaban

20 mg qd

Apixaban

5 mg bid

Stroke + SEE

non-infer

Superior

ITT cohort: non-infer.

On Rx cohort: Superior

Superior

ICH

Superior

Superior

Superior

Superior

Bleeding

Lower

similar

similar

Lower

Mortality

similar

P = 0.051

similar

Superior: P = 0.047

Ischemic stroke

similar

Lower

similar

similar

Mean TTR

64%

55%

62%

Stopped drug

21%

23%

23%

WD consent

2.3%

8.7%

1.1%

TTR = time in therapeutic range

WD consent = withdrawal of consent, no further data available

Efficacy of New Oral Anticoagulants

Stroke & SEE

Ischemic &

Unsp. Stroke

13%

Hemorraghic

Stroke

55%

Favors NOACs

Miller CS, et al. Am J Cardiol 2012;110(3):453-460.

Favors Warfarin

92

Safety of New Oral Anticoagulants

Bleeding

Major

51%

ICH

GI

Favors NOACs

iller CS, et al. Am J Cardiol 2012;110(3):453-460.

Favors Warfarin

Does INR Matter?

ROCKET AF

0.00-50.62%

50.71-58.54%

58.63-65.71%

65.74-100.0%

Treatment Group

Warfarin

P-value

Event Rate / Year Event Rate / Year (interaction)

0.74

1.77

2.53

1.94

2.18

1.90

2.14

1.33

1.80

RE-LY (Dabigatran 150 mg)

< 57.1%

1.1

57.1–65.5%

1.04

65.5–72.6%

1.04

> 72.6%

1.27

Hazard Ratio (95% CI)

Study Drug

Favors

Warfarin

0.20

1.92

2.06

1.51

1.34

ARISTOTLE

< 58.0%

58.0–65.7%

0.29

1.75

1.30

2.28

1.61

65.7–72.2 %

> 72.2 %

1.21

0.83

1.55

1.02

Wallentin L, et al. Lancet 2010;376:975-983

Patel, et al. NEJM 2011;365(10);883-891

Granger CB, et al. NEJM 2011; 365:981-992

0.2

1

www.fda.gov

2

5

All-Cause Death &

Thromboembolism

Warfarin Treatment Interruption

Raunsø J, et al. Eur Heart J 2012; 33:1886-1892

Novel Oral Anticoagulants

More Events “Off-Drug”

13%

25%

%/yr

P = 0.015

P = 0.117

ROCKET AF

Rivaroxaban Increased Events at End of Trial

81.3

# Primary Events

Warfarin

P = 0.008

48.8

Rivaroxaban

Rivaroxaban

Warfarin

# Primary Events during first 30 days of transition

Safety/Days 3 to 30 after the last dose

Patel MR, et al. NEJM 2011; 365:883-891

Piccini JP, AHA Emerging Science Series, April 25, 2012 webinar. Abstract 114

ARISTOTLE

Apixaban Increased Events at End of Trial

Days after

last dose

Apixaban to VKA group

n/N

Warfarin to VKA group

%/year

n/N

%/year

Stroke or systemic embolism

1–30

21/6791

4.02

5/6569

0.99

1–2

1/6791

2.69

1/6569

2.78

3–7

4/6787

4.31

0/6566

0

8–14

5/6780

3.85

1/6559

0.80

15–30

11/6771

4.18

3/6548

1.18

Pattern mirrored the first 30 days of the trial where warfarin-naïve patients starting

warfarin had a higher rate of stroke or systemic embolism (5.41%/year) than

warfarin-experienced patients (1.41%/year).

Granger CB, et al. European Heart Journal 2012; 23 (Supplement):685-686

“After the Deluge” of SPAF Trials

Translating Trials into Practice and

Guidelines: 2012 Update

Post-Trial, Real World Concerns, Guidelines,

and Actions—Where Have Landmark SPAF

Trials Taken Us? How Have Recent Guidelines

Made Sense of These Data?

NOACs Elevated to "Favored" Status by ESC

2012 Update Guidelines for

Management of AF

The net clinical benefit of VKAs, balancing ischaemic

stroke against ICH in patients with non-valvular AF, has been

modeled on to stroke and bleeding rates from the Danish

nationwide cohort study for dabigatran, rivaroxaban, and

apixaban, on the basis of recent clinical trial outcome data

for these NOACs. At a CHA2DS2-VASc score of 1, apixaban

and both doses of dabigatran (110 mg bid and 150 mg bid)

had a positive net clinical benefit while, in patients with

CHA2DS2-VASc score ≥ 2, all three NOACs were superior to

warfarin, with a positive net clinical benefit, irrespective of

bleeding risk.

2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: Europace. 2012 Aug 24

Assess bleeding risk

(HAS-BLED score)

Consider patient values

and preferences

NOAC

VKA

LINE SOLID = BEST OPTION

DASHED = ALTERNATIVE OPTION

2012 focused update of the ESC Guidelines for the management of atrial fibrillation: Europace. 2012 Aug 24

Bleeding Risk with Dabigatran

Fact vs Fiction

Bleeding Risk with Dabigatran

Fact vs Fiction: What Do Regulators Conclude?

Disconnect Between Clinical Trials and Post-Marketing

Surveillance Bias: A Case Study

EMA Report on Dabigatran: May 24, 2012

"What are the conclusions of the CHMP?

The CHMP concluded that the latest available data are

consistent with the known risk of bleeding and that the risk

profile of dabigatran was unchanged. The Committee

found that frequency of reported fatal bleedings with

dabigatran was significantly lower than what had been

observed in clinical trials at the time of authorisation, but

considered that the risks should nonetheless continue to

be kept under close review."

EMA Report on Dabigatran

May 24, 2012

What is the updated advice for prescribers?

Prescribers are reminded of the need to follow all the necessary

precautions with regard to the risk of bleeding with dabigatran,

including the assessment of kidney function before treatment in all

patients and during treatment if a deterioration is suspected, as well

as dose reductions in certain patients.

Dabigatran must not be used in patients with a lesion or condition

putting them at significant risk of major bleeding (see the revised

product information for details).

Dabigatran must not be used in patients using any other

anticoagulant, unless the patient is being switched to or from

dabigatran (see the revised product information for details).

A European Commission decision on this opinion will be issued in

due course.

Dabigatran vs. Warfarin: Surgical

Bleeding

, even

among patients having major or urgent

surgery. Patients receiving dabigatran were 4

times more likely to have their procedure or

surgery within 48 hours of withholding

anticoagulation

Circulation, Healey et al., 2012

ESC 2012 Atrial Fibrillation

Guidelines Update: Risk Assessment

Risk Profile

Class / Level

CHA2DS2-VASc = 0

No antithrombotic therapy

IB

CHA2DS2-VASc = 1

VKA (INR 2-3)

Or

Dabigatran / Rivaroxaban / Apixaban

IIa A (Favored)

CHA2DS2-VASc ≥ 2

VKA (INR 2-3)

Or

Dabigatran / Rivaroxaban / Apixaban

I A (Favored)

Conclusions: From Trials and

Evidence to Strategy and Practice

►

New therapies provide the promise of providing safer,

more effective, and more convenient anticoagulation.

Trials are consistent in reduction of intracranial

hemorrhage and bleeding mortality.

►

SPAF trials are consistent in demonstrating that NOACs

are at least as good as, and in some cases, superior to

warfarin in preventing stroke in patients with AF.

►

There are important differences in the PK/PD of these

agents (half-life, metabolism, renal elimination) that will

alter the risk/benefit profile in specific populations; in

particular, careful monitoring of renal function is a

precondition for optimizing safety and efficacy of these

agents.

Conclusions

►

No reversal agent is currently available but whether the

lack of such agents lead to increased bleeding or

mortality risk has not been substantiated.

►

New ESC 2012 Update Guidelines for AF have refined

and incorporated a new suite of risk prediction

strategies (CHA2DS2-VASc, HAS-BLED) that will result in

a greater proportion of patients being eligible for oral

anticoagulation.

►

New ESC 2012 Update Guidelines for AF have elevated

NOACs to "favored" status over VKA for patients who

meet risk stratification criteria for requiring oral

anticoagulation for AF.

New Paradigms in the

Science and Medicine of Heart Disease

Stroke Prevention in

Atrial Fibrillation

Megatrends, Challenges, and

Clinical Dilemmas

Samuel Z. Goldhaber, MD, Program Chairman

Director, VTE Research Group

Cardiovascular Division

Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Professor of Medicine

Harvard Medical School

Faculty COI Disclosures

Research Support

Eisai, EKOS, Johnson & Johnson, sanofi-aventis

Consultant

Baxter, Boehringer-Ingelheim, Bristol-Myers

Squibb, Daiichi, Eisai, Janssen, Merck, Pfizer,

Portola, sanofi-aventis

Risk Assessment Megatrend

►

CHA2DS2-VASc has replaced CHADS2 as the

predominant assessment tool to predict stroke

risk (ESC 2012 AF Guidelines Update).

►

HAS-BLED has gained dominance as the most

predictive bleeding index. It is best used as a

cautionary “yellow flag” rather than as a reason

to withhold anticoagulation (ESC 2012).

Clinical Dilemma and Challenge—

Stroke Risk Underestimated

►

Paroxysmal AF is difficult to detect.

►

24h Holter is often insufficient. Long-term

noninvasive or invasive monitoring may be

necessary.

►

Many strokes are misclassified as “cryptogenic”

and are treated with aspirin or other antiplatelet

agents, with questionable efficacy for AF.

►

The misclassified strokes are really

thromboembolic and warrant anticoagulants.

Subclinical AF and Risk of Stroke

Stroke or Systemic Embolism

Atrial tachyarrhythmia > 6 min ≤ 3 months after

pacemaker or defibrillator implantation

Healey JS, et al. NEJM 2012; 366:120-129

Years

Redefining Risk vs Benefit for OAC

HAS-BLED

Letter

Clinical

Characteristic

Points

H

Hypertension

1

Stroke

(% / yr)

A

Abnormal Liver

or Renal

Function

HAS-BLED

Score

1 or 2

0

1.1 %

1

1.0 %

S

Stroke

1

2

1.9 %

B

Bleeding

1

3

3.7 %

L

Labile INR

1

4

8.7 %

E

Elderly

(age > 65)

1

>5

?? %

Lip GYH. Am J Med. 2011;124:111-114.

D

Drugs or Alcohol

Maximum Score

1 or 2

9

ESC Guidelines: Eur Heart J . 2010;31:2369-2429.

Clinical Dilemma: Bleeding Risk

Correlates With Stroke Risk

►

The higher the bleeding risk, as assessed by the

HAS-BLED Index, the higher the stroke risk—A

“Catch 22” when considering and/or deploying

oral anticoagulation.

►

Based on observational and trial evidence, we

must be especially vigilant to prescribe

anticoagulation to AF patients at high risk of

bleeding, when the thrombosis risk assessment

justifies this course of action.

Action Plan When OAC is Indicated

and Patient Has High HAS-BLED Index

►

Modify bleeding risk factors.

►

Intensify surveillance for bleeding and for

triggers that cause bleeding.

►

Consider “renal dose” for NOAC, especially in the

presence of some renal dysfunction or frailty or

age ≥ 80 years.

►

Monitor renal function with vigilance.

►

Prescribe PPI when indicated.

Stroke and Bleeding in Atrial Fibrillation

with Chronic Kidney Disease

Danish

Registry

146,251

patients were

discharged with

nonvalvular atrial fibrillation (1997-2008)

13,879 were excluded

127,884 (96.6%) did

not have renal disease

3587 (2.7%) received a

diagnosis of non-end-stage

chronic kidney disease

4538 (3.5%) received a

diagnosis of non-end-stage

chronic kidney disease

Olesen JB. NEJM 2012; 367: 625-635

228 (6.4%) underwent

renal-replacement therapy

during follow-up

901 (0.7%) underwent

renal-replacement

therapy

Stroke Risk and Renal Disease

Aspirin does not prevent stroke

Characteristic

Total Population

(n = 132,372)

Hazard Ratio

(95% CI)

P Value

All participants

No Renal Disease

(n = 127,884)

Hazard Ratio

(95% CI)

P Value

1.00

Antithrombotic

Therapy

None

1.00

1.00

Warfarin

0.59 (0.57-0.62)

< 0.001

1.10 (1.06-1.14)

< 0.001

Aspirin

1.11 (1.07-1.15)

< 0.001

1.10(1.06-1.14)

< 0.001

Warfarin and

aspirin

0.70(0.65-0.75)

< 0.001

0.69(0.64-0.74)

< 0.001

Olesen JB. NEJM 2012; 367:625-635

Bleeding Risk and Renal Disease

Aspirin and warfarin/aspirin increase bleeding

Characteristic

Total Population

(n = 132,372)

Hazard Ratio

(95% CI)

P Value

All participants

No Renal Disease

(n = 127,884)

Hazard Ratio

(95% CI)

P Value

1.00

Antithrombotic

Therapy

None

1.00

1.00

Warfarin

1.28(1.23-1.33)

< 0.001

1.28(1.23-1.33)

< 0.001

Aspirin

1.21(1.16-1.26)

< 0.001

1.21(1.16-1.26)

< 0.001

Warfarin and

aspirin

2.15(2.04-2.26)

< 0.001

2.18(2.07-2.30)

< 0.001

Olesen JB. NEJM 2012; 367:625-635

Megatrend:

Recognizing Overuse of Aspirin

Role of aspirin in the setting of

SPAF is called into question.

Aspirin is often prescribed for “CAD prevention,”

without a clear evidence-based rationale, thus

increasing bleeding risk when combined with OACs

used for SPAF. Evaluate necessity for ASA.

Dosing Options for Renal Dysfunction

Consider also for age ≥80, weight ≤ 60 KG (frailty)

►

Dabigatran 75 mg bid (USA)

►

Dabigatran 110 mg bid (non-USA)

►

Rivaroxaban 15 mg daily

25%

►

Apixaban 2.5 mg bid

50%

ESC 2012

50%

Dilemmas in “Under-Anticoagulation”

►

Anticoagulants clearly prevent stroke in AF

patients but are markedly underutilized

►

Failure to prophylax in the setting of nonvalvular AF is characterized by fear of:

●

●

●

●

Bleeding

Older age

Renal dysfunction

Lack of medication adherence

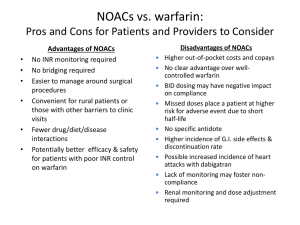

Dilemmas: NOACs vs Warfarin

►

By most metrics, NOACs are the “best option”

for SPAF (ESC 2012 Update for AF)

►

Failure to prescribe NOACs is characterized by:

●

●

●

●

Lack of familiarity

Lack of reversal agent

Inability to measure NOAC level

Inertia, fear of change, “preapprovals”

NOACs vs Warfarin—

A View From 30,000 Feet

►

NOACs generally more effective than warfarin

for stroke prevention

►

NOACs are generally safer (less bleeding, with

some exceptions, but NOACs uniformly cause

less intracranial hemorrhage, most devastating

and mortality-inducing bleeding complication of

OAC)

►

NOACs, overall, reduce mortality

►

NOACs are more convenient for patient/clinician

New Anticoagulant Therapies Compared

to Warfarin: All-cause Mortality

Dabigatran 150 mg b.i.d.

Dabigatran 110 mg b.i.d.

Rivaroxaban 20 mg o.d.

Abixaban 5 mg b.i.d.

0.5

Connolly S et al NEJM 2009; Patel M et al NEJM

2011; Granger CB et al NEJM 2011

1

2

Limitations of Novel Agents are

Exaggerated

No antidote when bleeding

• Best treatment is prevention

• Warfarin has no great antidote

• Time is a great antidote

No antidote for urgent procedures

• RELY analysis 2012 shows no

increase in bleeding in this

setting

Lack standard measurement

• Do not need one

• Time since last dose is helpful

Dependence on renal function

• Rivaroxaban, apixaban modest

renal effect

Cost

• Highly cost effective in analyses

Deciphering the Pharmaco-economic Maze

“Cost-effectiveness”

Cost: Must take into account the costs of

caring long-term for debilitated

thromboembolic stroke patients and the costs

of caring for intracranial hemorrhage when

doing a “cost-effectiveness” analysis of

NOACs vs warfarin.

However, we continue to have mostly

“silo budgeting.”

Cost of Dabigatran vs Warfarin

► Dabigatran retail: $240/month

► Warfarin discount retail: $4/month

► Will the high price of dabigatran cause poor

medication adherence?

“The cost of medical care looms as the single largest

threat to the US economy.”

Avorn J. Circulation 2011: 123: 2519-2521

Prevent > 50% AF Cases by Modifying

Cardiovascular Risk Factors

►

N = 14,598 middle-aged subjects

►

Over 17 years, 1520 incident cases of AF in

the Atherosclerosis Risk in Communities

(ARIC) Study

►

56% of cases explained by elevated CV risk

factors, especially hypertension, obesity,

diabetes, and smoking

Circulation 2011; 123: 1501-1508

Guidelines for “Bridging”with

Dabigatran (RE-LY)

Renal Function

Impairment

(CrCL mL/min)

Estimated Halflife, h (Range)

Stopping Dabigatran Before

Surgery/Procedure

High Risk for

Bleeding

Standard Risk

for Bleeding

Mild:

> 50 to 80

15 (12-18)

2-3d*

24 h (2 doses)

Moderate:

> 30 to < 50

18 (18-24)

4d

At least 2 d

(48 h)

Severe: < 30

27 (> 24)

> 5d

2-4 d

Healey JS. Circulation 2012; 126: 343-348

Interrupting Dabigatran and Warfarin

RE-LY

►

1 of 4 patients underwent peri-procedural

anticoagulant interruption

►

Stroke rate: 0.5%; major bleeding rate:

4%, 7 days pre- to 30 days post

►

Dabigatran was withheld an average of 2

days, whereas warfarin was withheld an

average of 5 days preop

Healey JS. Circulation 2012; 126: 343-348

Medication Adherence Failure

►

Failing to fill or refill a prescription

►

Omitting doses

►

Overdosing

►

Prematurely discontinuing medication

►

Taking someone else’s medication

►

Taking a medication with prohibited foods

►

Taking outdated medications

Questions Regarding the New

Non-Monitored, Oral Anticoagulants

►

Do they represent a significant improvement

for patients who have been taking warfarin

with consistently therapeutic INR values for months

or years? They may.

►

Will the elimination of regular INR measurement

reduce or improve compliance?

►

How will their cost compare to current costs

(including INR monitoring, dose adjustment, etc)?

Selecting Patients for Non-Monitored

Oral Anticoagulation (NOAC)

Clinical Dilemma #1

►

Which patients are the best candidates for nonmonitored oral anticoagulation? Treatment-naive and de

novo patients? And/or patients on warfarin?

►

Established patients on warfarin doing "well?"

Established on warfarin, doing well, but at high risk for

bleeding? High HAS-BLED? Previous stroke?

►

On warfarin, and doing "reasonably" well, but requiring

multiple interventions to keep INR/TTR controlled?

►

Patients on warfarin who are doing well, but only with

intensive monitoring?

Transitioning Patients from Warfarin to a

Non-Monitored Oral Anticoagulant

Clinical Dilemma #2

►

How do we actually transition patients from

warfarin to dabigatran, rivaroxaban, apixaban, or

other agents?

►

What INR do we wait for?

►

What are the renal issues that need to be

considered for each agent?

How do I Convert a Patient from

Warfarin to Dabigatran and Vice Versa?

► Warfarin to dabigatran: Discontinue warfarin and start

dabigatran when the international normalized ratio

(INR) is below 2.0.

► Dabigatran to warfarin:

• CrCl > 50 mL/min, start warfarin 3 days before discontinuing dabigatran.

• CrCl 31-50 mL/min, start warfarin 2 days before discontinuing dabigatran.

• CrCl 15-30 mL/min, start warfarin 1 day before discontinuing dabigatran.

• CrCl < 15 mL/min, no recommendations can be made.

Because dabigatran can contribute to an elevated INR, the INR

will better reflect warfarin’s effect after dabigatran has been

stopped for at least 2 days.

Dabigatran prescribing information 2010

Managing Patients Who Are on Non-Monitored

Oral Anticoagulation and Have Had a Stroke

Clinical Dilemma #3

►

How do we approach a patient who has had an

embolic stroke while on a non-monitored oral

anticoagulant?

►

Should we switch? Why? Why not?

►

To what agent would we switch? From one nonmonitored oral anticoagulant to another? To warfarin?

►

If we switch to warfarin, at what INR? What if the

patient is at risk for hemorrhage?

What Should I Do if my Patient Has

an Ischemic Stroke on Dabigatran?

►

Consider:

●

●

●

●

Is the patient compliant with dabigatran? Check

aPTT or thrombin time– if dose taken within past

12 hours, these levels should be prolonged.

If the stroke is cryptogenic, consider adding

antiplatelet therapy.

Convert dabigatran to warfarin (target INR 2-3 or

higher?).

Switch to another NOAC?

Aligning Specific Patient and Risk Profiles with

Specific NOACS: Apixaban, Dabigatran, Rivaroxaban

Clinical Dilemma #4

►

Based on AVERROES, RE-LY, ARISTOTLE, and ROCKETAF, should we be aligning specific, non-monitored oral

anticoagulants with specific risk groups?

►

Should the warfarin-intolerant/ineligible patient be

"steered" toward apixaban?

►

The "high-risk" patient be steered toward rivaroxaban?

►

The intermediate-risk patient be "steered" toward

apixaban or dabigatran?

►

How do we know whether this kind of alignment is

evidence-based, or if it is an artifact of the trial designs?

What Should We Use For Hemorrhage on a NonMonitored Oral Anticoagulant?

Clinical Dilemma #5

►

What should be our clinical approach to a patient

who has had a hemorrhage on a non-monitored

oral anticoagulant?

►

Does it depend on the type of hemorrhage?

Other factors?

►

Should we ever consider warfarin in these

patients?

Guide to the Management of

Bleeding in Patients Taking NOAC

Patients with bleeding on NOAC therapy

Moderate-Severe

bleeding

Mild bleeding

• Delay next dose or

discontinue treatment

as appropriate

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Mechanical compression

Surgical intervention

Fluid replacement and

hemodynamic support

Blood product transfusion

Oral charcoal

Hemodialysis

? Prothrombin Complex

Concentrate?

Life-threatening

bleeding

• Consideration of rFVIIa

or PCC

• Charcoal filtration

• ? Prothrombin Complex

Concentrate

(Circulation 2011; 2011: 124:

1573-9)

(Circulation 2011; 2011: 124: 1573-9)

Hankey GJ and Eikelboom JW. Circulation. 2011; 123: 1436-1450

Antithrombotic Agents

A New Era of “Alignment and Flexibility?”

►

Dabigatran: Superior SPAF compared with warfarin

►

Rivaroxaban: Once-daily administration and less

dependence on kidneys for metabolism; non-inferior in

ITT analysis in very high-risk patient population

►

Apixaban: Safety equivalent to aspirin in AVERROES,

and superior stroke prevention in warfarin intolerant or

ineligible

►

Apixaban: Superior SPAF, less major bleeding, lower

all-cause mortality.

SPAF Clinical Trial Programs

Translational Dilemmas and Cautionary Notes

►

Do clinical trial results apply to “real world”

medicine in busy clinical practices with brief office

visits and minimal telephone follow-up?

►

Are patients who participate in clinical trials

healthier/more motivated than most? Does this

make favorable results more likely in both the new

drug and the comparison groups?

►

Do the costs of a “copay” affect patient decisions

to fill a prescription for a potentially more effective,

safer drug vs a less expensive but less effective

alternative?

Unresolved Issues with NOACs

►

No established methods of monitoring

►

No known therapeutic ranges

►

Lack of a proven antidote

►

Uncertain management of bleeding

►

Long term safety: to be determined

►

No head-to-head comparisons of new agents

Properties of Ideal Anticoagulant

Do NOACS Fit the Bill?

►

Proven efficacy √

►

Low bleeding risk √

►

Fixed dosing √

►

Good oral bioavailability √

►

No routine monitoring needed √

►

Reversibility: ?PCC, FEIBA, rVIIa

►

Rapid onset of action √

►

Few drug or food interactions √

NOACs: Advancing Opportunities

to Connect Guidelines with Practice

►

Lower stroke rates

►

Fewer major and fatal bleeds, especially ICH

►

Lower dose options for chronic kidney disease,

elderly, and the “frail” or “underweight” patient

►

Use in conjunction with RF reduction: treat

congestive heart failure, diabetes, hypertension,

obesity

►

Facilitate periprocedural treatment

►

Should improve medication adherence—no

injections/ no routine lab blood testing

Advances in the Science and Medicine

of Stroke Prevention in AF

So What Now? Trials in Translation

Applying Evidence-Driven Strategies to AF

Patients at the Front Lines of Clinical Practice

Audience Response System-Based Interactions

Samuel Z. Goldhaber, MD

Program Chairman

Director, VTE Research Group

Cardiovascular Division

Brigham and Women’s Hospital

Professor of Medicine

Harvard Medical School

Atrial Fibrillation Case Study #1

► A 71-year-old white female with a history of

chronic, non-valvular AF, controlled hypertension,

and a history of mild congestive heart failure has

been evaluated by a cardiologist and found to be

a suitable candidate for warfarin therapy.

► Due to logistical barriers that make monitoring

difficult and dietary variations, the patient has

had difficulty controlling her INR.

► Wide fluctuation in her INR has made her

question continued warfarin therapy.

Audience Response System (ARS) Question

► Because of her high risk for embolic stroke, her

cardiologist is considering alternative forms of

thromboprophylaxis for SPAF. She has a HAS-BLED

SCORE of 2.

► Which of the following should we consider? Are any

of these strategies optimal in this patient type?

1) Keep patient on warfarin

2) Replace warfarin with aspirin

3) Replace warfarin with aspirin + clopidogrel

4) Replace warfarin with a non-monitored oral anticoagulant

Atrial Fibrillation Case Study #2

► An 81-year-old white female with a history of chronic,

non-valvular AF, a history of a previous ischemic

stroke, and a history of mild congestive heart failure

has been on a combination of clopidogrel and aspirin

therapy because she was found to be intolerant of

warfarin.

► She is on a proton pump blocker, an ACE inhibitor, a

diuretic, and digoxin.

► She is admitted to the hospital for a GI bleed, and is

found to have a hematocrit of 29 and a hemoglobin

of 9.8. The aspirin and clopidogrel are discontinued.

Atrial Fibrillation Case Study #2

The patient stabilizes, and the cardiologist is

consulted to determine the subsequent course of her

antithrombotic treatment. She has a HAS-BLED score

of 3.

It is your opinion that:

1) Because of the documented GI bleed, the patient should

not be treated with antithrombotic agents, because the

risk of bleeding outweighs the risk of stroke and its

complications.

2) Because of the patient's risk profile, there should be an

attempt to provide thromboprophylaxis against embolic

stroke.

Atrial Fibrillation Case Study #2

The cardiologist has determined that this

patient requires antithrombotic management

for stroke prevention.

At this point you would most likely:

1) Try the patient on warfarin again

2) Try to re-introduce clopidogrel and aspirin

3) Treat the patient with aspirin alone

4) Introduce a non-monitored oral anticoagulant to

the patient's regimen.

Atrial Fibrillation Case Study #3

► An 82-year-old man with hypertension and

diabetes has permanent atrial fibrillation.

► He has a history of spinal stenosis and walks

with a walker and has a history of falls.

► He has a CHADS-VASc score of 3, and a HAS—

BLED score of 2.

► Which regimen would you prescribe for

prophylaxis against thromboembolism?

Atrial Fibrillation Case Study #3

Which regimen would you prescribe for

prophylaxis against thromboembolism?

1. Warfarin (INR 2.0-3.0)

2. Warfarin (INR 1.5-2.0)

3. Aspirin 81 mg daily

4. Aspirin 81 mg + clopidogrel 75 mg daily

5. An oral Factor Xa or direct thrombin inhibitor

Atrial Fibrillation Case Study

Anticoagulation in Patients at Risk of Falls

“…persons taking warfarin must fall about

295 (535/1.81) times in 1 year for

warfarin not to be the optimal therapy…”

Atrial Fibrillation Case Study #4

A 71-year-old man with AF, heart failure, and a prior

history of stroke presents with unstable angina and

proceeds to cardiac catheterization where a culprit

lesion is identified. Optimal management includes:

1) Placement of a drug-eluting stent with plan to continue

anticoagulation in addition to 1 year of dual antiplatelet

therapy

2) Placement of a drug-eluting stent with 1 year of dual

antiplatelet therapy alone

3) Placement of a bare metal stent with plan to continue

anticoagulation in addition to 1 month of dual antiplatelet

therapy

4) Placement of a bare metal stent with 1 month of dual

antiplatelet therapy alone

Atrial Fibrillation Case Study #5

A 67-year-old female with a history of mitral

stenosis with subsequent mechanical mitral valve

replacement has AF.

Which of the following anticoagulants can be used

for stroke prevention in this patient?

1) Warfarin

2) Dabigatran

3) Apixaban

4) Rivaroxaban

5) All of the above

Atrial Fibrillation

Knowledge Assessment Question

The major potential benefits of the new nonmonitored oral anticoagulants include:

1) Rapid therapeutic anticoagulant effect

2) Greater safety with regards to intracranial hemorrhage

3) Proven reversal agent

4) All of the above

5) Both 1 and 2

Atrial Fibrillation Case Study #6

An 82-year-old man with AF has had several admissions

over the past 6 months for heart failure complicated by

worsening renal function. His creatinine clearance is

currently 20 mL/min but frequently fluctuates to 10-15

mL/min. He has a HAS-BLED score of 3.

The best anticoagulant regimen for stroke prevention is:

1) Dabigatran 150 mg twice daily

2) Dabigatran 75 mg twice daily

3) Warfarin titrated to goal INR 2-3

4) Rivaroxaban 20 mg once daily

5) Rivaroxaban 15 mg once daily

Atrial Fibrillation Case Study #7

A 79-year-old woman with a CHADS-VASc score of

2 who has been on warfarin for the past 2 years

returns to clinic for routine follow-up.

Her INR control has been excellent and she has

never experienced a stroke or had significant

bleeding. Her HAS-BLED score is 2.

Her complaints today are thinning hair, cold

intolerance, and fatigue.

Her laboratory work is normal including a TSH.

Atrial Fibrillation Case Study #7

Which of her symptoms could be due to warfarin?

1) Thinning hair

2) Cold intolerance

3) Fatigue

4) Both 1 and 2

5) All of the above

Atrial Fibrillation Case Study #8

A 69-year-old woman with AF and CHADS2 score

of 4 has a creatinine clearance that is stable at 40

mL/min.

Which of the following anticoagulation regimens

are suitable for her?

1) Dabigatran 150 mg twice daily

2) Dabigatran 75 mg twice daily

3) Rivaroxaban 20 mg once daily

4) Rivaroxaban 15 mg once daily

5) Both 1 and 4

Atrial Fibrillation Case Study #8

What would her options be if her creatinine

clearance was stable at 25 mL/min?

1) Dabigatran 75 mg twice daily

2) Rivaroxaban 15 mg once daily

3) Only warfarin can be used in patients with creatinine

clearance < 30 mL/min

4) Both 1 and 2

Atrial Fibrillation Case Study #9

A 74-year-old man with AF on dabigatran is

involved in a motor vehicle accident and needs

emergency surgery.

It is unclear if he is taking this medication but

the surgeon is concerned about operating on

him if he is fully anticoagulated.

Atrial Fibrillation Case Study #9

Which of the following lab tests, if normal, would

reassure the team that the patient is not

anticoagulated?

1) INR (international normalized ratio)

2) aPTT (activated partial thromboplastin time)

3) PT (prothrombin time)

4) Bleeding time

Atrial Fibrillation Case Study #10

A 60-year-old man with AF has been on warfarin

but it has been very difficult to control his INR.

You have decided to switch to dabigatran. Which

of the following is true regarding transitioning a

patient from warfarin to dagibatran?

1) Start dabigatran when his INR < 3

2) Start dabigatran when his INR < 2

3) Start dabigatran 24 hours after his last dose of warfarin

Atrial Fibrillation Case Study #10

What if you decided to switch the patient to

rivaroxaban?

1) Start rivaroxaban when his INR < 3

2) Start rivaroxaban when his INR < 2

3) Start rivaroxaban 24 hours after his last dose of

warfarin

Atrial Fibrillation Case Study #11

A 78-year-old female with AF, systolic heart failure,

hypertension, diabetes, and a history of significant GI

bleeding has been on warfarin for many years but has

had a difficult time controlling her INR with frequent

supertherapeutic values despite intensive monitoring

and titration of her warfarin dose. Her HAS-BLED

score is 3. The best treatment option for her is:

1) No antithrombotic therapy

2) Discontinue warfarin and start aspirin

3) Discontinue warfarin and start dabigatran

4) Discontinue warfarin and start rivaroxaban

5) Discontinue warfarin and start apixaban

Atrial Fibrillation Case Study #12

A 76-year-old woman with heart failure, hypertension,

diabetes, and declining renal function (creatinine

clearance 35 mL/min) has an embolic stroke due to

newly diagnosed AF. She refuses to take warfarin.

What is the best validated antithrombotic regimen in

this particular patient?

1) Aspirin

2) Aspirin and clopidogrel

3) Dabigatran

4) Apixaban

5) Rivaroxaban

Atrial Fibrillation Case Study #13

A 68-year-old man with a mechanical mitral valve

develops AF.

The best anticoagulant option for him is:

1) Warfarin

2) Dabigatran

3) Apixaban

4) Rivaroxaban

5) Aspirin

Atrial Fibrillation Case Study #14

A 76-year-old man with heart failure and hypertension

undergoes successful catheter ablation for

symptomatic AF.

Which of the following is true regarding his

anticoagulation management?

1) He no longer requires anticoagulation now that he is in

sinus rhythm

2) Patient should be on both aspirin and an anticoagulant

3) Patient should be on an anticoagulant alone

4) Aspirin and clopidogrel together is as effective as

anticoagulation in these patients

Atrial Fibrillation Case Study #14

The cardiologist has determined that this

patient requires antithrombotic management for

stroke prevention. At this point you would most

likely:

1) Try the patient on warfarin again

2) Treat the patient with aspirin alone

3) Introduce the non-monitored oral anticoagulant,

apixaban, into the patient's regimen

4) Introduce dabigatran into the patient’s regimen

5) Introduce rivaroxaban into the patient’s regimen

Atrial Fibrillation Case Study #15

► A 75-year-old male with a history of chronic,

non-valvular AF, diabetic renal disease,

previous history of ischemic stroke, history of

mild HF, and controlled hypertension has been

on warfarin therapy. The HAS-BLED score is 4.

► For the past 6 months, despite repeated visits

for monitoring and warfarin dose adjustment,

his INR has varied between 1.5 and 4.3.

► His estimated GFR is 30 mL/min.

Atrial Fibrillation Case Study #15

At this point you would:

1) Continue to try to stabilize his INR on warfarin

2) Change to aspirin alone

3) Introduce the non-monitored oral anticoagulant rivaroxaban

into the patient's regimen

4) Introduce the non-monitored oral anticoagulant apixaban