Product Liability

advertisement

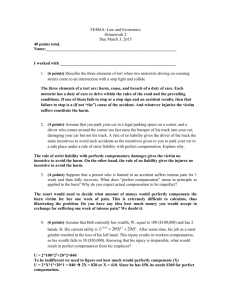

Regulatory due care standard Statutory due care standard Common law due care standard Reasonable man Custom Hand rule A [health care provider/doctor] is required to use the same degree of learning, care, and skill ordinarily used by other qualified [providers/doctors] in good standing practicing in the same [specialty/field]. This is known as the “standard of care.” The failure to follow the standard of care is a form of fault known as “medical malpractice.” To establish medical malpractice, [name of plaintiff] has the burden of proving three things: (1) first, what the standard of care is; (2) second, that the [provider/doctor] failed to follow this standard of care; and (3) third, that this failure to follow the standard of care was a cause of [name of plaintiff]’s harm. In this action, [name of plaintiff] alleges that [name of defendant] failed to follow the standard of care in the following respects: (1) (2) (3) If you find that the [name of defendant] breached the standard of care in any of these respects, then you must determine whether that failure was a cause of [name of plaintiff]’s harm. Regulation is ex ante enforcement by administrators, and liability is ex post enforcement by victims Bankrupt firms may escape liability Litigation may be expensive Administrators may set standards better than courts, so the court may use a safety regulation as the standard of care for determining liability Courts may disregard regulatory standard when assigning damages A trial provides judges with better information about the harm caused by an accident than administrators can obtain Courts often have fewer political motives than administrators A court to distrust the legal standard imposed by a safety regulation Defect in design Defect in manufacture Defect in warning Third Restatement of Torts "A product is defective in design when the foreseeable risks of harm posed by the product could have been reduced or avoided by the adoption of a reasonable alternative design ... and the omission of the alternative design renders the product not reasonably safe." In most cases the defects with respect to design and manufacturing are unilateral The producer is also the one most likely to be aware of special dangers Benefits and Costs Relating to Fuel Leakage Associated with the Static Rollover Test Portion of FMVSS208 From Ford Motor Company internal memorandum: "Fatalities Associated with Crash-Induced Fuel Leakage and Fires." Damages (1960s) Accidents 180 burn deaths 180 serious burn injuries 2,100 burned vehicles Related accident costs $200,000 per death $67,000 per injury $700 per vehicle ($2,000 new vehicle) From Ford Motor Company internal memorandum: "Fatalities Associated with Crash-Induced Fuel Leakage and Fires." Total Benefits from eliminating problem 180 x ($200,00) + 180 x ($67,000) + 2,100 x ($700) = $49.7 million From Ford Motor Company internal memorandum: "Fatalities Associated with Crash-Induced Fuel Leakage and Fires." Cost of eliminating problem Sales: 11 million cars, 1.5 million trucks Unit cost: $11 per car, $11 per truck Total cost: 11 million x ($11) + 1.5 million x ($11) = $137 million Result: Costs ($137) exceed benefits ($49.5) The Ford Pinto Case Benefits equal cost when the value of a statistical life is $685,900 In February of 1978, a California jury created a nationwide sensation when it awarded the record-breaking sum of $128 million in a lawsuit stemming from a Pinto accident NHTSA Estimate of the Value of Life Component 1971 Cost Future Productivity Losses Direct $132,000 Indirect 41,300 Medical Costs Hospital 700 other 425 Property damage 1,500 Insurance Admin. 4,700 Legal and Court 3,000 Employer losses 1,000 Pain and Suffering 10,000 Funeral 900 Assets (lost consumption) 5,000 Miscellaneous accident cost 200 The Value of Life $200,725 Defects in manufacturing are unilateral. While placing bottles of Coca Cola in the refrigerator, a bottle explodes in the hand of a grocer store clerk, seriously injuring her hand. There is no evidence that the bottle was mishandled and there is evidence that other bottles have exploded spontaneously. The court concludes that the bottle was defective. Given that the bottle was defective is that sufficient proof that Coca Cola was negligent? res ipsa loquitur (rayz ip-sah loh-quit-her) n. Latin for "the thing speaks for itself," Does the defect prove negligence? (1) defendant had exclusive control of the thing causing the injury and (2) the accident is of such a nature that it ordinarily would not occur in the absence of negligence by the defendant. “…the evidence appears sufficient to support a reasonable inference that the bottle here involved was not damaged by any extraneous force after delivery to the restaurant by defendant. It follows, therefore, that the bottle was in some manner defective at the time defendant relinquished control, because sound and properly prepared bottles of carbonated liquids do not ordinarily explode when carefully handled.” Suppose there was no way of producing bottles that were 100 percent safe? How would we know this without examining production standards and the cost of production? Would the courts have enough information to establish a due care standard in Coca Cola? What about medical tests or vacines? Is precaution unilateral? Behavior Production costs P(x) A P(x)A Full cost Use bottles 40 cents 1/100,000 $10,000 10 cents 50 cents Use cans 43 cents 1/200,000 $4,000 2 cents 45 cents • Imperfectly informed customers may not choose the most efficient product under no liability • The choice between no liability and strict liability is actually a choice between victims’ insurance against accidents and injurers’ insurance against liability Transfers risk from the insured party to the insurance company Externalizes risk Moral hazard problems may be reduced by Deductibles and co-payments Experience ratings Subrogation Not appropriate for punitive damages Insurance does not provide perfect compensation Some are most likely bilateral in nature. Will the warning be heeded? Suppose the manufacturer could not avoid liability for customer misuse? All customers would pay a higher price Careful customers would subsidize careless customers The implicit cost of insurance is tied to the price of the product Careful customers may be denied products that produce a consumer surplus Swix v Daisy Manufacturing, US District Court 2004 373 F.3d 678 Cooter and Ulen on product liability The most efficient rule may be strict liability with defense of contributory negligence After losing the use of his eye, Aaron, a minor, and his parents brought a product liability action against the manufacturer of the air rifle that his 11-year-old friend used to shoot him. The case claimed that the air rifle was defectively designed. The lower court dismissed the claim a gun is a “simple tool” under Michigan law and the dangers of pointing it at another person are “open and obvious.” There is no need to warn of a danger where the danger is obvious The product itself telegraphs the precise warnings the plaintiffs claim is lacking The appeals court found that a gun was a simple tool. However, the lower court failed to apply the reasonable child standard. A manufacturer who bypasses adults, upon whom the law ordinarily places responsibility, and markets a simple, but dangerous, tool directly to children may not avoid liability on the ground that the child should have known better The fact that Daisy intended that its air rifle be used under the direct supervision of an adult and that Swix’s grandfather had the same rule does not alter the “reasonable child standard” In a related Pennsylvania case the company settled for $18 million • Liability costs may be passed on to consumers in higher product price • Reduction in quantity demanded due to higher price • Price premium may function like insurance. All pay more for few who are harmed • Premium may subsidize the most careless among us • Product may be withdrawn from market denying product to consumer who would willingly accept risk. • With no liability consumers may make inefficient decisions because they cannot accurately assess risks. Consider accidents involving power tools. One might suppose that precaution in such cases is bilateral: there is something that both the consumer and the producer can do to reduce the probability and severity of an accident. As a result, the economic theory would suggest that some form of the negligence rule should be used to induce efficient precaution by both consumers and producers. However, suppose that there was strong evidence that consumers could not accurately assess the risks associated with the use of power tools. They might presume that the tools are so safe that they need not take any particular care in how they are used. In short, consumers might mistakenly assume that the probability of an accident is zero and take very little precaution. That fact would make this a situation of unilateral, rather than bilateral, precaution: only manufacturers could realistically be expected to take steps to reduce the probability and severity of an accident.3 In these circumstances, manufacturers might be held liable for failing to design a product that would prevent foreseeable misuse by consumers. Firefighter rule Good Samaritan protection Public policy rule Precludes a firefighter from recovering from one whose negligence causes or contributes to a fire that in turn causes injury or death to the firefighter There is an assumption of risk May be limited to premises liability and ordinary negligence Gross negligence and intentional harm is not ordinarily protected An owner or occupier of private property can be liable to a fire fighter or police officer who enters the premises and is injured in the performance of his or her official job duties if (1) the injury was caused by the owner's or occupier's willful or wanton misconduct or affirmative act of negligence; (2) the injury was a result of a hidden trap on the premises; (3) the injury was caused by the owner's or occupier's violation of a duty imposed by statue or ordinance enacted for the benefit of fire fighters, or police officers; or (4) the owner or occupier was aware of the fire fighter's or police officer's presence on the premises, but failed to warn them of any known, hidden danger thereon. Provides protection from ordinary negligence when providing emergency assistance Medical professionals are not ordinarily protected There may be no general duty to render assistance No person shall be liable in civil damages for administering emergency care or treatment at the scene of an emergency outside of a hospital, doctor’s office, or other place having proper medical equipment, for acts performed at the scene of such emergency, unless such acts constitute willful or wanton misconduct. Nothing in this section applies to the administering of such care or treatment where the same is rendered for remuneration, or with the expectation of remuneration, from the recipient of such care or treatment or someone on his behalf. The administering of such care or treatment by one as a part of his duties as a paid member of any organization of law enforcement officers or fire fighters does not cause such to be a rendering for remuneration or expectation of remuneration. Damages would run counter to public policy goals A victim should not benefit from their own criminal behavior A bomb maker sued those who sold him the gunpowder A suit by a burglar against the homeowner for faulty stairs An injured person can sue those who contributed to the injurer’s intoxication Dram shop laws Social host laws There was a special duty of care because the injurer was invited to drink Findlaw: Ohio Social Host Law