Thyroid Disorders

Dr Muries Barham

ENDOCRINOLOGEST

Thyroid Disorders

• Anatomy

The thyroid gland consists of two lateral

lobes connected by an isthmus. It is closely

attached to the thyroid cartilage and to the

upper end of the trachea, and thus moves on

swallowing.It is often palpable in normal

women.

• The normal thyroid is 12–20 g in size, highly

vascular, and soft in consistency. Four

parathyroid glands, which produce PTH,are

located posterior to each pole of the thyroid.

The recurrent laryngeal nerves traverse the

lateral borders of the thyroid gland and must

be identified during thyroid surgery to avoid

injury and vocal cord paralysis.

• Synthesis. The thyroid synthesizes two

hormones, L-thyroxine (T4) and

triiodothyronine (T3), of which T3 acts at the

cellular level and T4 is the prohormone.

The thyroid axis is a classic example of an

endocrine feedback loop. Hypothalamic TRH

stimulates pituitary production of TSH, which,

in turn, stimulates thyroid hormone synthesis

and secretion.

• Thyroid hormones, acting predominantly

through thyroid hormone receptor 2 (TR2),

feed back to inhibit TRH and TSH production.

The "set-point" in this axis is established by

TSH.

TRH is the major positive regulator of TSH

synthesis and secretion. Peak TSH secretion

occurs 15 min after administration of

exogenous TRH. Dopamine, glucocorticoids,

and somatostatin suppress TSH but are not of

major physiologic importance except when

these agents are administered in

pharmacologic doses

Thyroid function tests

• TSH levels can discriminate between

hyperthyroidism, hypothyroidism and

euthyroidism. There are pitfalls, however.

These are mainly with hypopituitarism, with

the ‘sick euthyroid’ syndrome, all of which

may give ‘false’ ,low results implying

hyperthyroidism.

• As a single test of thyroid function it is the

most sensitive in most circumstances, but

accurate diagnosis requires at least two tests –

for example, TSH plus free T4 or free T3 where

hyperthyroidism is suspected, TSH plus serum

free T4 where hypothyroidism is likely

Causes of Hypothyroidism

• Primary Autoimmune hypothyroidism: Hashimoto's

thyroiditis, atrophic thyroiditis

• Iatrogenic: 131I treatment, subtotal or total

thyroidectomy, external irradiation of neck for

lymphoma or cancer

• Drugs: iodine excess (including iodine-containing

contrast media and amiodarone), lithium, antithyroid

drugs, p-aminosalicylic acid, interferon- and other

cytokines, aminoglutethimide, sunitinib

• Congenital hypothyroidism: absent or ectopic thyroid

gland, dyshormonogenesis, TSH-R mutation

Causes of Hypothyroidism

Iodine deficiency

Infiltrative disorders: amyloidosis, sarcoidosis,

hemochromatosis, scleroderma, cystinosis,

Riedel's thyroiditis

Transient -Silent thyroiditis, including postpartum

thyroiditis ,Subacute thyroiditis

-Withdrawal of thyroxine treatment in individuals

with an intact thyroid

- After 131I treatment or subtotal thyroidectomy for

Graves' disease

Causes of Hypothyroidism

Secondary

-Hypopituitarism: tumors, pituitary surgery or

irradiation, infiltrative disorders, Sheehan's

syndrome, trauma, genetic forms of combined

pituitary hormone deficiencies

-Isolated TSH deficiency or inactivity

-Hypothalamic disease: tumors, trauma,

infiltrative disorders, idiopathic

Essentials of Diagnosis

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Symptoms

Tiredness, weakness

Dry skin

Feeling cold

Hair loss

Difficulty concentrating and poor memory

Constipation

Weight gain with poor appetite

Dyspnea

Hoarse voice

Menorrhagia (later oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea)

Paresthesia

Impaired hearing

Signs

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Dry coarse skin; cool peripheral extremities

Puffy face, hands, and feet (myxedema)

Diffuse alopecia

Bradycardia

Peripheral edema

Delayed tendon reflex relaxation

Carpal tunnel syndrome

Serous cavity effusions

Atrophic (autoimmune) hypothyroidism.

This is the most common cause of hypothyroidism and

is associated with antithyroid autoantibodies leading to

lymphoid infiltration of the gland and eventual atrophy

and fibrosis. It is six times more common in females

and the incidence increases with age. The condition is

associated with other autoimmune disease such as

pernicious anaemia, vitiligo and other endocrine

deficiencies . In some instances intermittent

hypothyroidism occurs with recovery from disease;

antibodies which block the TSH receptor may

sometimes be involved in the aetiology.

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis

This form of autoimmune thyroiditis,again

more common in women and most common

in late middle age, produces atrophic changes

with regeneration,leading to goitre formation.

The gland is usually firm and rubbery but may

range from soft to hard.

Hashimoto’s thyroiditis

• TPO antibodies are present, often in very high

titres (> 1000 IU/L). Patients may be

hypothyroid or euthyroid, though they may go

through an initial toxic phase, ‘Hashi-toxicity’.

Levothyroxine therapy may shrink the goitre

even when the patient is not hypothyroid.

Postpartum thyroiditis

This is usually a transient phenomenon

observed following pregnancy. It may cause

hyperthyroidism , hypothyroidism or the two

sequentially. It is believed to result from the

modifications to the immune system

necessary in pregnancy, and histologically is a

lymphocytic thyroiditis.

Postpartum thyroiditis

• The process is normally self-limiting, but when

conventional antibodies are found there is a

high chance of this proceeding to permanent

hypothyroidism. Postpartum thyroiditis may

be misdiagnosed as postnatal depression

Subacute Thyroiditis

• Subacute thyroiditis(de Quervain's Thyroiditis;

Giant Cell Thyroiditis; Granulomatous

Thyroiditis) is an acute inflammatory disease

of the thyroid probably caused by a virus.

Symptoms include fever and thyroid

tenderness. Initial hyperthyroidism is

common, sometimes followed by a transient

period of hypothyroidism

Subacute Thyroiditis

• History of an antecedent viral URI is

common.

• Diagnosis is clinical and with thyroid function

tests.

• Treatment is with high doses of NSAIDs or

with corticosteroids. The disease usually

resolves spontaneously within months.

Subacute Thyroiditis

• Symptoms and Signs

There is pain in the anterior neck and fever

of 37.8° to 38.3° C. Neck pain characteristically

shifts from side to side and may settle in one

area, frequently radiating to the jaw and ears.

Defects of hormone synthesis

• Iodine deficiency. Dietary iodine deficiency

still exists in some areas. The patients may be

euthyroid or hypothyroid depending on the

severity of iodine deficiency

• Dyshormonogenesis. This rare condition is

due to genetic defects in the synthesis of

thyroid hormones; patients develop

hypothyroidism with a goitre.

Myxedema Coma

• uncommon but life-threatening form of

untreated hypothyroidism . The condition

occurs in patients with long-standing,

untreated hypothyroidism.

Myx. Coma-Precipitating factors

• CNS depressants(barbiturates,

phenothiazines, narcotics, anaesthetics)

• Infections

• Trauma

• Hypothermia

• Hypoventilation

• Old age

Hypothyroidism & Myxedema Coma

• Myxedema Coma Findings:

– Decrease mental status – from baseline

– Hypothermia/ Hypoglycemia/ Hyponatremia

– Bradycardia(soft distant heart sounds,enlarged

heart with or without pericardial effusion).

– Hypoventillation

– Peri-orbital edema

– Non-pitting Edema

– Delayed Tendon Reflexes

Management of Myxedema

• ICU admission may be required for

ventilatory support and IV medications

• levothyroxine intravenously (myxedema

itself can interfere with levothyroxine's

intestinal absorption).

– Loading dose of 300 – 400 μg

– Then 50 μg daily

• The hypothermic patient is warmed only with

blankets, since faster warming can precipitate

cardiovascular collapse.

• Patients with hypercapnia require intubation

and assisted mechanical ventilation.

• Infections must be detected and treated

aggressively.

Management of Myxedema

• Electrolytes

– Hypertonic saline or IV glucose may be needed

if there is severe hyponatremia or

hypoglycemia; hypotonic IV fluids should be

avoided because they may exacerbate water

retention secondary to reduced renal perfusion

and inappropriate vasopressin secretion

• Avoid sedation

Prognosis of Myxedema

• Glucocorticoids - Parenteral hydrocortisone

(50 mg every 6 h) should be administered,

because there is impaired adrenal reserve in

profound hypothyroidism.for 1 week, then

taper.

• Mortality is 20%, and is mostly due to

underlying and precipitating diseases

• Before therapy with thyroid hormone is

commenced, the hypothyroid patient requires

at least a clinical assessment for adrenal

insufficiency, for which the patient would

require evaluation and concurrent treatment.

Thyrotoxicosis

• Thyrotoxicosis is defined as the state of

thyroid hormone excess and is not

synonymous with hyperthyroidism, which is

the result of excessive thyroid function.

Causes of Thyrotoxicosis

• Primary hyperthyroidism

1-Graves' disease

2-Toxic multinodular goiter

3-Toxic adenoma Functioning thyroid carcinoma

metastases

4- Activating mutation of the TSH receptor

5- Activating mutation of Gs (McCune-Albright

syndrome)

6-Struma ovarii

7-Drugs: iodine excess (Jod-Basedow phenomenon)

Thyrotoxicosis without

hyperthyroidism

• Subacute thyroiditis

• Silent thyroiditis

• Other causes of thyroid destruction:

amiodarone, radiation, infarction of adenoma

• Ingestion of excess thyroid hormone

(thyrotoxicosis factitia) or thyroid tissue

Secondary hyperthyroidism

• TSH-secreting pituitary adenoma

• Thyroid hormone resistance syndrome:

occasional patients may have features of

thyrotoxicosis

• Chorionic gonadotropin-secreting tumors

• Gestational thyrotoxicosis

Graves' Disease

• Graves' disease accounts for 60–80% of

thyrotoxicosis. The prevalence varies among

populations, reflecting genetic factors and

iodine intake (high iodine intake is associated

with an increased prevalence of Graves'

disease).

• Graves' disease occurs in up to 2% of women

but is one-tenth as frequent in men. The

disorder rarely begins before adolescence and

typically occurs between 20 and 50 years of

age; it also occurs in the elderly.

• Graves' disease is currently viewed as an

autoimmune disease of unknown cause.

There is a strong familial predisposition in that

about 15% of patients with Graves' disease

have a close relative with the same disorder,

and about 50% of relatives of patients with

Graves' disease have circulating thyroid

autoantibodies.

. Proposed environmental triggers include

stress, tobacco use, infection, and iodine

exposure. The postpartum state, which may

be associated with heightened immune

function, also may trigger the development of

Graves' disease in genetically susceptible

women.

Symptoms

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Hyperactivity, irritability, dysphoria

Heat intolerance and sweating

Palpitations

Fatigue and weakness

Weight loss with increased appetite

Diarrhea

Polyuria

Oligomenorrhea, loss of libido

Signs

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

•

Tachycardia; atrial fibrillation in the elderly

Tremor

Goiter

Warm, moist skin

Muscle weakness, proximal myopathy

Lid retraction or lag

Gynecomastia

ophthalmopathy and dermopathy

• Graves' disease is caused by an autoantibody

against the thyroid receptor for thyroidstimulating hormone (TSH); unlike most

autoantibodies, which are inhibitory, this

autoantibody is stimulatory, thus causing

continuous synthesis and secretion of excess

T4 and T3.

• Graves' disease (like Hashimoto's thyroiditis)

sometimes occurs with other autoimmune

disorders, including type 1 diabetes mellitus,

vitiligo, premature graying of hair, pernicious

anemia, connective tissue diseases, and

polyglandular deficiency syndrome.

• The pathogenesis of infiltrative

ophthalmopathy (responsible for the

exophthalmos in Graves' disease) is poorly

understood but may result from

immunoglobulins directed to specific

receptors in the orbital fibroblasts and fat that

result in release of proinflammatory cytokines,

inflammation, and accumulation of

glycosaminoglycans

• Ophthalmopathy may also occur before the

onset of hyperthyroidism or as late as 20 yr

afterward and frequently worsens or abates

independently of the clinical course of

hyperthyroidism.

Treatment: Graves' Disease

• Graves' disease is treated by reducing thyroid

hormone synthesis, using antithyroid drugs, or

reducing the amount of thyroid tissue with

radioiodine (131I) treatment or by thyroidectomy.

Antithyroid drugs are the predominant therapy in

many centers in Europe and Japan, whereas

radioiodine is more often the first line of

treatment in USA. No single approach is optimal

and that patients may require multiple

treatments to achieve remission.

• The common side effects of antithyroid drugs

are rash, urticaria, fever, and arthralgia (1–5%

of patients). These may resolve spontaneously

or after substituting an alternative antithyroid

drug.

• Rare but major side effects include hepatitis;

an SLE-like syndrome; and, most important,

agranulocytosis (<1%). It is essential that

antithyroid drugs are stopped and not

restarted if a patient develops major side

effects.

• symptoms of possible agranulocytosis (e.g.,

sore throat, fever, mouth ulcers) and the

need to stop treatment pending a complete

blood count to confirm that agranulocytosis is

not present.

• Beta blockers (Propranolol (20–40 mg every 6

h) or longer-acting such as atenolol), may be

helpful to control adrenergic symptoms,

especially in the early stages before

antithyroid drugs take effect. The need for

anticoagulation with Warfarin should be

considered in all patients with atrial

fibrillation.

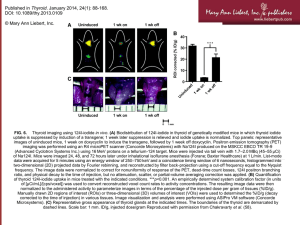

Radioiodine

• causes progressive destruction of thyroid cells

and can be used as initial treatment or for

relapses after a trial of antithyroid drugs.

There is a small risk of thyrotoxic crisis after

radioiodine, which can be minimized by

pretreatment with antithyroid drugs for at

least a month before treatment.

• Antithyroid drugs should be considered for all

elderly patients or for those with cardiac

problems to deplete thyroid hormone stores

before administration of radioiodine.

Carbimazole or methimazole must be stopped

at least 2 days before radioiodine

administration to achieve optimum iodine

uptake.

Thyrotoxic crisis, or thyroid storm

• Is rare and presents as a life-threatening

exacerbation of hyperthyroidism,

accompanied by fever, delirium, seizures,

coma, vomiting, diarrhea, and jaundice. The

mortality rate due to cardiac failure,

arrhythmia, or hyperthermia is as high as 30%,

even with treatment.

• Thyrotoxic crisis is usually precipitated by

acute illness (e.g., stroke, infection, trauma,

diabetic ketoacidosis), surgery (especially on

the thyroid), or radioiodine treatment of a

patient with partially treated or untreated

hyperthyroidism.

• Management requires intensive monitoring

and supportive care, identification and

treatment of the precipitating cause, and

measures that reduce thyroid hormone

synthesis. Large doses of Antithyroid drugs

should be given orally or by nasogastric tube.

• One hour after the first dose of antithyroid

drug. A saturated solution of potassium iodide

(5 drops SSKI every 6 h).

• Propranolol should also be given to reduce

tachycardia and other adrenergic

manifestations (40–60 mg PO every 4 h; or 2

mg IV every 4 h). Although other -adrenergic

blockers can be used, high doses of

propranolol decrease T4 T3 conversion, and

the doses can be easily adjusted.

• Additional therapeutic measures include

glucocorticoids (e.g., dexamethasone, 2 mg

every 6 h), antibiotics if infection is present,

cooling, oxygen, and intravenous fluids.

Subclinical hyperthyroidism

• Patients with serum TSH < 0.1 mU/L have an

increased incidence of atrial fibrillation

(particularly elderly patients), reduced bone

mineral density, increased fractures, and

increased mortality. Patients with serum TSH

that is only slightly below normal are less

likely to have these features.

Subclinical hyperthyroidism

• Many patients with subclinical hyperthyroidism

are taking L-thyroxine; in these patients,

reduction of the dose is the most appropriate

management unless therapy is aimed at

maintaining a suppressed TSH in patients with

thyroid cancer or nodules. The other causes of

subclinical hyperthyroidism are the same as those

for clinically apparent hyperthyroidism.

Subclinical hyperthyroidism

• Therapy is indicated for patients with

endogenous subclinical hyperthyroidism

(serum TSH < 0.1 mU/L), especially those with

atrial fibrillation or reduced bone mineral

density. The usual treatment is 131I. In patients

with milder symptoms (eg, nervousness), a

trial of antithyroid drug therapy is worthwhile.

Subclinical Hypothyroidism

• Subclinical hypothyroidism is elevated serum TSH in

patients with absent or minimal symptoms of

hypothyroidism and normal serum levels of free T4.

• Subclinical thyroid dysfunction is relatively common; it

occurs in more than 15% of elderly women and 10% of

elderly men, particularly in those with underlying

Hashimoto's thyroiditis.

Subclinical Hypothyroidism

• In patients with serum TSH > 10 mU/L, there is

a high likelihood of progression to overt

hypothyroidism with low serum levels of free

T4 in the next 10 yr. These patients are also

more likely to have hypercholesterolemia and

atherosclerosis. They should be treated with Lthyroxine, even if they are asymptomatic

Subclinical Hypothyroidism

• For patients with TSH levels between 4.5 and

10 mU/L, a trial of L-thyroxine is reasonable if

symptoms of early hypothyroidism (eg,

fatigue, depression) are present. L-Thyroxine

therapy is also indicated in pregnant women

and in women who plan to become pregnant

to avoid deleterious effects of hypothyroidism

on the pregnancy and fetal development.

Subclinical Hypothyroidism

• Patients should have annual measurement of

serum TSH and free T4 to assess progress of

the condition if untreated or to adjust the Lthyroxine dosage

Approach to the Patient With a Thyroid Nodule

• Thyroid nodules are common, increasingly so

with increasing age. In middle-aged and

elderly patients, palpation reveals nodules in

about 5%. Results of ultrasonography and

autopsy studies suggest that nodules are

present in about 50% of adults. Many nodules

are found incidentally on thyroid imaging

studies done for other disorders.

Etiology

• Most nodules are benign.

• Benign causes include hyperplastic colloid

goiter, thyroid cysts, thyroiditis, and thyroid

adenomas. Malignant causes include thyroid

cancers.

Evaluation

• History: Pain suggests thyroiditis or

hemorrhage into a cyst. An asymptomatic

nodule may be malignant. Symptoms of

hyperthyroidism suggest a hyperfunctioning

adenoma or thyroiditis, whereas symptoms of

hypothyroidism suggest Hashimoto's

thyroiditis.

Risk factors for thyroid cancer

• History of thyroid irradiation, especially in infancy or childhood

• Age < 20 yr

• Male sex

• Family history of thyroid cancer or multiple endocrine neoplasia

• A solitary nodule

• Dysphagia

• Dysphonia

• Increasing size (particularly rapid growth or growth while receiving

thyroid suppression treatment).

• Physical examination: Signs that suggest

thyroid cancer include stony hard consistency

or fixation to surrounding structures, cervical

lymphadenopathy, and hoarseness due to

recurrent laryngeal nerve paralysis.

• If TSH is suppressed, radioiodine scanning is

done. Nodules with increased radionuclide

uptake (hot) are seldom malignant. If thyroid

function tests do not indicate hyperthyroidism

or Hashimoto's thyroiditis, or if nodules are

indeterminate or cold, FNA biopsy is done to

distinguish benign from malignant nodules.

• Ultrasonography is useful in determining the

size of the nodule but is rarely diagnostic of

cancer .Fine-needle aspiration biopsy is not

routinely indicated for nodules < 1 cm on

ultrasonography.

THANK YOU