Theories for Pre-Hospital and In-Hospital Resuscitation

advertisement

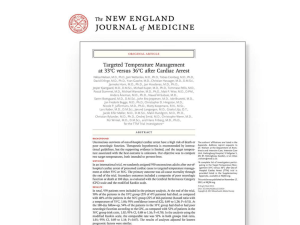

Update on Hypothermia post Cardiac Arrest. E Hessel, II, MD, FACS Strive to Revive: Improving Cardiac Resuscitation American Heart Association and UK HealthCare Gill Heart Institute Lexington, KY April 28, 2014 Revised April 28, 2012; 0530 EDST Disclosures • I have no disclosures, financial or otherwise. This is why I am speaking on this topic: Starting in 2003 therapeutic hypothermia (TH) has been strongly recommended following some Cardiac Arrests (CA) by many professional organizations including most recently by the American Heart Association • Last year at this meeting I critiqued the use of therapeutic hypothermia (TH) post cardiac arrest especially post inhospital cardiac arrest (IH-CA) – Pointed out the limitations of the evidence supporting its use for outof-hospital cardiac arrest (OOH-CA)… – and the lack of any high level evidence of its benefit following cardiac arrest associated with non-shockable rhythms and following in-hospital cardiac arrest (IH-CA). My Objectives For this afternoons presentation • Elaborate and expand on some of the data I presented last year • Review important data which have appeared during in the literature during the past year • Give you my personal current recommendations regarding the use of therapeutic hypothermia post cardiac arrest. I call your attention, and have provided copies for you, of an article of mine recently published on this topic, largely based on my presentation at this meeting last year but including some of the new information which I will present this afternoon. I am referring you to this paper mainly because it provides references to many of the studies I will be commenting on this afternoon J Cardiothoracic and Vascular Anesthesia Epub ahead of print. April 18, 2014 Outline • TH for OOH-CA – • TH for CA associated with non-shockable rhythms – • Recent large observational study Role of simply preventing hyperthermia post CA – • Recent systematic review and some new data TH for IH-CA – • A new large observational study with concurrent controls Recent large RCT 36o versus 33o C Role of pre-hospital cooling – Recent RCT • Ongoing Pediatric RCTs • Review limitations of TH • Selection of candidates for TH • Summary Use Therapeutic Hypothermia (TH) following Out-of-Hospital Cardiac Arrest (OOH-CA) • Still no randomized controlled trials since the two major ones published 12 years ago (2002) • There have been – A RCT of benefits of pre-hospital cooling (prior to in-hospital TH) – A RCT comparing a targeted temperature of 36o C versus traditional 33o C – I will review these studies subsequently • In addition the results of a large data registry has been recently reported (see next.) Mader TJ, etal. Therapeutic Hypoth and Temp management 2013; 4(1): 21-31 Retrospective cohort study of patients resuscitated from out-of-hospital Cardiac Arrest using data from the Cardiac Arrest Registry to Enhance Survival (CARES) [CDC and Emory University] ~ 50 sites Nov 1, 2010 through Dec 31, 2012 Adults with CA of presumed cardiac etiology with survival to hospital admission; included shockable and non-shockable l rhythms Propensity score matching to compare patients receiving therapeutic hypothermia or not 6369 patients Shockable 47%; asystole 26%, PEA 20%, other non-shockable 7% Therapeutic hypothermia in 54% (62% of shockable, 50% on non-shockable) Mader TJ, etal. Therapeutic Hypoth and Temp management 2013; 4(1): 21-31 Mader TJ, etal. Therapeutic Hypoth and Temp management 2013; 4(1): 21-31 Unadjusted outcomes (Mader, et al. 2014) Rhythm All – TM – No TM Shockable – TM – No TM Non-shockable – TM – No TM n Survived(%) Good Neurologic Outcome(CPC 1 or 2)(%) 3452 2917 40% 39 34% 34 1851 1141 60 65 53 61 1601 1776 17 22 12 16 Note outcome no better or worse with TH Mader TJ, etal. Therapeutic Hypoth and Temp management 2013; 4(1): 21-31 Mader TJ, etal. Therapeutic Hypoth and Temp management 2013; 4(1): 21-31 Mader TJ, etal. [Therapeutic Hypoth and Temp management 2013; 4(1): 21-31] TH following Cardiac Arrest Associated with Non-shockable rhythms. • Last year I stated “Although there are conflicting data, most suggest that TH is less beneficial, (or perhaps not even beneficial) post nonshockable rhythms following (either out-of-hospital or in-hospital cardiac arrest)” • Unfortunately this remains true today – There have been three new observational studies, and – Two systematic review and Meta-analyses of this issue • But the definitive answer awaits large well conducted RCT or prospective observational studies. TH following CA associated with non-shockable rhythms • Recent observational studies that provide information – Vaahersalo J, et al. Intensive Care Med 2013; 39: 826-37 – Lindner TW, et al. Critical Care 2013; 17: R147 – Mader, et al. Ther Hypth and Temp Manag 2014; 4: 21-30 • Recent reviews – Kim Y-M, et al. Resuscitation 2012; 83: 188-96 – Sandroni C, et al. Critical Care 2013:17: 215 A recent Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Sandroni C, etal. Critical Care 2013; 17: 217 Death Bad neurologic Outcome Sandroni, et al Critical Care 2013; 17:215 TH following CA associated with non-shockable rhythms My Summary of these data Studies of effect of therapeutic hypothermia in patients following Cardiac arrest associated with non-shockable rhythms (PEA or asystole) Add Mader, et al’s large observational study in 2014 Hessel, EA. J Cardiothoracic and Vascular Anesthesia Epub ahead of print. April 18, 2014 TH following CA associated with non-shockable rhythms Summary • The Studies – Two small (total of 22 patients in each arm) – 16 non-randomized observations studies • Type of controls – 5 with concurrent controls – 11 with historical controls • Patients – 546 received TH (+ 1601 from Mader, etal 2014) – 1038 did not (+ 1776 from Mader, etal 2014) TH following CA associated with non-shockable rhythms Summary • The Results – Impact on survival (13 studies) • 11 observed no statistically significant difference • 2 observed an improved survival with TH • In aggregate: 12% decrease in mortality with TH (No decrease if include Mader, etal, 2014) – Impact on good neurologic recovery (14 studies) • 13 observed no statistically significant difference • 1 observes an improved outcome with TH • In aggregate: A statistically insignificant 5% increase in good neurologic outcome with TH (No improvement if include Mader, etal, 2014) • Conclusion – There is a suggestion of benefit with use of TH in some studies – Magnitude much less that seen in patients with shockable rhythms – Because of the low quality of the evidence (GRADE) there is need for high quality RCTs to confirm any benefit Unadjusted outcomes (Mader, et al. 2014) Rhythm Non-shockable – TM – No TM n Survived(%) Good Neurologic Outcome(CPC1 or 2)(%) 1601 17 12 1776 22 16 Worse outcome! Mader TJ, etal. Therapeutic Hypoth and Temp management 2013; 4(1): 21-31 Mader TJ, etal. [Therapeutic Hypoth and Temp management 2013; 4(1): 21-31] In-Hospital Cardiac Arrest Edelson DP, etal. J Hospital Med 2014 epub ahead of print (90%) NEJM 2012; 367: 1912-20 GWTG-R Investigators 374 hospitals 2000-2009 84,625 cardiac arrests Initial rhythm asystole or PEA in 79% (and increased over time from 69 to 82%) Survival to discharge 17% If VF or VT 34% If Asystole or PEA 10% Neurologic disability in survivors 30% Survival to discharge increased over time while neurologic disability decreased S. Girotra, etal. NEJM 2013. Therpeutic hypothermia after in-hospital Cardiac arrest Mikkelsen ME, etal. CCM 2013 Additional comments and observations • 210,000 in hospitals cardiac arrests (IHCA) annually in USA • Rate is increasing • Less than 25% have VF/VT as the initial rhythm (and this appears to be declining) • IHCA with initial non-shockable rhythm that transitions to VF/VT is common and outcomes are dismal (Meaney, etal. CCM 2010; 38: 101) • No RCT of TH following IH-CA have been reported TH following In-hospital Cardiac Arrest • Last year I indicated that there was no high level evidence (e.g., RCT or large observational studies demonstrating improved outcome with therapeutic hypothermia when used following in-hospital cardiac arrest. • This remains true, however during the past year the largest retrospective observational study addressing this question was published. I will review this shortly. Hessel, EA. J Cardiothoracic and Vascular Anesthesia Epub ahead of print. April 18, 2014 Nichol G, et al. Resuscitation 2013; 84: 620-25 Retrospective analysis of multi-center prospective cohort of patients 454 hospitals in USA participating in Get With the Guidelines-Resuscitation (TWTG-R) QI 2000-2009 Limited to adult patients with ROSC after in-hospital CA on the ward (i.e., excluded if arrest in ER, ICU, OR, procedure areas or recovery areas) 8316 patients 214 (2.6%) received hypothermia, 8102 did not 87% had non-shockable rhythms 41% were unwitnessed 1374 (13%) had shockable rhythms (similar rate in both groups) Nichol G, et al. Resuscitation 2013; 84: 620-25 Primary outcome: Survival to discharge Secondary outcome: Good neurological status at discharge (CPC score 1 or 2) Provided unadjusted and propensity score adjusted Odds Ratios Results: Overall non-statistically significant worse outcome in hypothermia group In those with shockable rhythms [n 1374 (13%] non-statistically significant better outcome with hypothermia Table 2. Effect of hypothermia on survival and favorable neurologic outcome at discharge in entire population Nichol G, et al. Resuscitation 2013; 84: 620-25 Table 4. Effect of hypothermia on survival and favorable neurologic outcome at discharge in patients with shockable rhythms Nichol G, et al. Resuscitation 2013; 84: 620-25 However only 51% of those receiving hypothermia were documented to have been cooled to below 34o C This may explain the lack of benefit Reasons to anticipate that therapeutic hypothermia might be less effective for In-hospital CA (IHCA) • More than 75% associated with non-shockable rhythms • IH-CA often due to hemorrhage, respiratory insufficiency or pulmonary embolism (instead of primary arrhythmias or AMI) • Victims of In-Hospital CA are often “sicker” and have more co-morbidities – Girotra, etal NEJM 2013 • 44% respiratory insufficiency • 29% hypotension • 20% heart failure • 17% sepsis • 15% pneumonia • 58% in ICU • 31% on mechanical ventilation • 29% receiving intravenous vasopressors Reasons to anticipate that therapeutic hypothermia might be less effective for In-hospital CA (IHCA) • Diagnosis of cardiac arrest often delayed – Between 12 and 48 % unwitnessed • These patients may be more prone to the complications of TH • Poor outcome following IH-CA less likely to be due to neurologic injury. (See next two slides) Mode of death after admission to an ICU following cardiac arrest. Laver S, etal. Intensive Care Med 2004; 30: 2126-28 Retrospective observational study of 225 patients single ICU in UK, 1998-2003 N Mean age (years) Died (percent) Cause of death (percent) Neurologic Cardiovascular Multi-organ failure OOH-CA IH-CA 113 63 57% 92 72 66% 68% 23 9 23% 26 51 So why might patients who experience CA associated with nonshockable rhythms and In-hospital be resistant to the benefits of TH? It is reasonable to assume that the pathophysiology of the neurologic injury (ischemia/reperfusion) is the same regardless of the rhythm or location of the arrest or these other variables TH modulates this injury and therefore it is plausible to expect it to be beneficial in these other circumstances. However the magnitude of neurologic injury could be much worse in these scenarios, and thus TH, as currently administered, may not be adequate [not a high enough “dose” (e.g., timing, depth and duration), to use the phrase of Dumas, etal (Circulation 2011) So why might patients who experience CA associated with nonshockable rhythms and In-hospital be resistant to the benefits of TH? Possible contributors to worse neurologic injury include: Delayed diagnosis (not infrequently unwitnessed), longer delay in ROSC, and more post resuscitation shock. Since many of these other victims of CA are less likely to have a cardiogenic cause, and the CA is often preceded by periods of cardio-respiratory failure (and associated hypotension and hypoxemia), their brains may have been somewhat ischemic even before the arrest occurs, aggravating the brain injury due to the CA per se. In-hospital Cardiac arrest • But there may be a unique population of patients who experience in-hospital cardiac arrest and this may have implications in our post arrest therapy… • Specifically peri-operative IH-CA Ramachandran SK, et al. Anesthesiology 2013; 119: 1322-39 Study of outcome of 2524 adults experiencing Cardiac Arrest in the operating room or within 24 hours post-operatively. (2.1 % of all in-hospital cardiac arrests) Obtained from the Get With The Guidelines-Resuscitation (GWTG-R) national in-hospital resuscitation registry (Perioperative arrests occurred in 234 hospitals 2000-2008 Location of arrest OR PACU ICU Wards Telemetry 1458 (57.5%) 536 332 140 58 • Outcome – ROCS – Hospital survival – Neurologically intact( (CPC 1) 57.7% 32% 19% • (64% of hospital survivors) • Factors associated with survival – Shockable rhythms (better survival) – Occurrence in PACU and telemetry units (better survival) – Arrests attributed to arrhythmias and inadequate natural airway (improved survival) – Trauma and shock worse survival – Number of coexisting diseases (survival decrease with number) – Age (decreases with age) – Duration of arrest (decreases with increase duration) – Time to defibrillation and placement of invasive airway (shorter better) • Factors associated with worse neurologic outcome – – – – – – Poor pre arrest neurological status Older age Inadequate natural airway Pre-arrest ventilator support Longer duration of event NOT the initial CA rhythm In survivors Good Neurological Outcome Among all patients 16.1% 19.9% 27.1% Comparison of Perioperative with All In-hospital Cardiac arrests (Get with the Guidelines-Resuscitation Registry) All IH-CA@ Periop CA* • Initial rhythm – Shockable – Non-shockable • Outcome – Survival to Discharge – Good neurologic outcome • All patients • In survivors – Survival per initial rhythm • Shockable • Non-shockable @Girotra 21% 79 24% 76 17 32 11 20 67 64 34 10 42 28.5 S, et al. NEJM 2012; 367: 1912-20 *Ramachandran SK, et al. Anesthesiology 2013; 119: 1322-39 Why better outcome following Perioperative cardiac arrest? Hypotheses • Shorter time to defibrillation, epinephrine and until invasive airway placement • Surgical causes for cardiac arrest are more likely to be reversible including medication and airway causes • Immediate availability of skilled physicians The Authors’ Conclusions Impact of baseline neurologic status on outcome % Surv 39.6% 22.6 19.6 6 • Last year I posited that “Intriguingly, it may be that simply preventing hyperthermia may be as effective as inducing mild hypothermia following resuscitation from cardiac arrest.” • A recent large RCT has been published that seems to support this hypothesis. Nielsen N, et al. NEJM 2013; 369 (23): 2197-2206 Prospective RCT 939 unconscious patients following Out-of Hospital Cardiac Arrest Note that this included nearly 3 times as many patients as the two prior RCTs of TH combined (350) 36 ICUs in Europe and Australia Inclusion criteria ≥18 year old, Admitted to hospital Unconscious (GCS < 8) after Out-of-Hospital cardiac arrest of presumed cardiac cause with any rhythm (but 80% shockable, 12% asystole. 7% PEA Randomized to temperature target of -33o or -36o Primary outcome: All cause mortality to end of trial Secondary outcomes: Neurologic outcome (blinded assessors) Cerebral Performance Category (CPC) at discharge from ICU, Hospital, and end of trial Serious adverse events Nielsen N, et al. NEJM 2013; 369 (23): 2197-2206 • Temperature management – Cooled to assigned temperature (33o or 36o C) as rapidly as possible and maintained for 28 hrs – Then rewarmed at 0.5o/ hour – Then, if unconscious, kept below 37.5o for 72 hrs post arrest. – Sedated until end of intervention. • Results: – No difference in any outcome measures between the two groups. Nielsen N, et al. NEJM 2013; 369 (23): 2197-2206 Note that by aiming for a temperature of 36o, temperature was kept below 37.2o in 97.5% of the patients in that group Nielsen N, et al. NEJM 2013; 369 (23): 2197-2206 Nielsen N, et al. NEJM 2013; 369 (23): 2197-2206 No difference in incidence of Serious Adverse Events Nielsen N, et al. NEJM 2013; 369 (23): 2197-2206 Pre-hospital Cooling Kim F, et al. JAMA 2014; 311(1): 45-52 Note profound effect of rhythm on mortality and neurologic recovery ~65% ~ 20% Pre hospital cooling (by IV infusion of cold saline) was associated with more pulmonary edema and lower PaO2 early. Accompanying Editorial Granger CB and Becker LB, JAMA 2014; 311(1): 31-32 TH following IH-CA Even if we don’t know for sure that it will help… What’s the harm in trying? • Potential complications of TH Infection, pneumonia, sepsis, hemodynamic instability, arrhythmias, hyperglycemia, coagulopathy, bleeding, electrolyte abnormalities, polyuria, seizures, altered drug metabolism • Complicates other care (e.g., angiography, interventional cardiology ) • Expensive, labor intensive • Diverts resources (staff, ICU beds, money) • False sense of hope for family • Conversely, failure to use may suggest to the family that the hospital/physicians are not providing optimal care (they have heard about TH in lay press) • Inhibits the ability to conduct badly needed RCTs. Complications of TH • Recent Reviews: – Soleimanpour H et al. Review. J CV Thor Res 2013; 6(1): 1-8 – Noyes AM and Lundbye JB. J Intens Care Med 2014, epub ahead of print. • In Nielsen, et al’s recent RCT comparing 33o with 36oC, found no significant differences in complication rate. • One potentially troublesome problem… Joffe J, et al. Resuscitation 2014, epub ahead of print Compared stent thrombosis (ST) rate after PCI for AMI 155 without Cardiac Arrest ST 2.0% 55 with CA (all received TH at 33oC for 24 hours 10.9 Not known if true and if so if related to CA per se or TH, or both TH could have contributed Did not receive oral DAT drugs pre procedure Hypothermia may activate platelets Hypothermia may inhibit effect of Clopidogrel Hypothermia may alter pharmacokinetics and dynamics of drugs Stent thrombosis following PCI post TH • Penela, D. JACC 2013; 61: 2013 – 31% in TH group (5/11) vs. 0.7 in others • Ibrahim, K. Eur Heart J 2011, 32: (suppl): 253 – 14.8% in TH (4/27) • Rosillo SO, et al. JACC 2014; 63(9): 939-49 – 2..3% in TH (2/77) Furthermore, even if we opt to employ it, We really don’t know how implement it optimally! • • • • • • • • • • • • • Time window of therapeutic effectiveness Optimal method of inducing and maintaining cooling Optimal temperature Optimal duration How to rewarm Where/ how to measure temperature Proper sedation and muscle relaxation Need for EEG monitoring Seizure detection and management Management of shivering, hypotension, hypertension Neurologic assessment How to assess neurologic prognosis Criteria for and when to withdraw Other’s Assessment Morrison LJ, et al. Circ 2013; 127: 1538-62 (i.e Kim et al’s pre hospital cooling trial, and Nielsen etal’s 36o vs 33o C TTM trial) • Thus I believe there is an increase skepticism being raised about the benefit of therapeutic hypothermia post cardiac arrest, if not questions about how it should be applied and to whom. Despite what I and some others consider to be limited evidence supporting the use of Therapeutic Hypothermia post Cardiac Arrest there are still many (perhaps a majority) who are strong advocates • • • • • • • • Nolan JP. Clin Med 2011, BMJ 2011 Kern KB. JACC Caridvasc Interv 2012 Boutsikaris D Emerg Med Clin NA 2012 Delhaye C etal. JACC 2012 Varon J, et al. Am J Emerg Med 2012 Scirica BM Circulation 2013 Da Silva and Frontera. Cardiol Clinic 2013; 31: 637-55 Perman SM, et al. Chest 2014; 145(2): 386-93 Intra-Arrest Hypothermia • CBS Sunday Morning, yesterday, April 27, 2014 – “Brought back from the dead” segment Sam Parnia, MD, PhD. Director of CPR research at Stony Brook School of Medicine; Director of AWARE “Today, cooling devices do much the same thing as that icy stream: it chills people whose hearts have stopped and preserves their brains until doctors can figure out how to get their hearts going again. “Cooling buys us time. So, for example, if somebody were to suddenly collapse and die at home, what we could do is go into the freezer and take out our frozen peas, frozen vegetables, put them on the body, and try to do CPR at the same time, so we can slow down the rate by which they're getting brain damage.“ !!! I could find no reference to any published work on Intra-arrest Hypothermia in PubMed by Dr. Parnia although he has published a book for the general public on this topic (“Erasing Death”, Harper, 2013) Scolletta S, et al. Critical Care 2012: 16: R41 Our pediatric colleagues are attempting to answer some of the questions regarding the efficacy of TH post CA with RCTs Ongoing Pediatric RCTs (Children <18 years old) • THAPCA Trials – Comparison groups • Hypothermia (32-34oC) for 48hrs followed by 3 days of “normothermia” (3637.5oC) versus • 5 days of “normothermia” – Primary outcome: Neurological outcome at 12 months – Two studies • NCT 0080087 (n = 350): In-hospital CA • NCT 00878644 (n = 500): Out-of-hospital CA • Two pilot studies – NCT 00754481 (Phase II, n = 40) • 48 hours of hypothermia versus 48 hours normothermia • Primary outcome: Neurological outcome at 12 months – NCT 00797680 (Phase II, N = 40) • 72 hours of hypothermia versus 24 hours of hypothermia • Outcome: Brain injury per plasma biomarkers and MRI Selection of candidates for TH Ebell MH, et al. JAMA Intern Med 2013; 173: 1-7 Used the GWTG-R Registry 2007-2009 51,240 IHCA in 366 hospitals Determined which pre-arrest characteristics predicted good neurologic outcome (CPC 1) at discharge Then tested in a validation group Designed to help patients/families make an informed DNR decision (? Could it also be used to help inform the decision as to who to utilize aggressive post arrest therapies) Ebell MH, et al. JAMA Intern Med 2013; 173: 1-7 Ebell MH, et al. JAMA Intern Med 2013; 173: 1-7 27% 1.4% Ebell MH, et al. JAMA Intern Med 2013; 173: 1-7 Summary • The use of TH is based upon the presumed pathophysiology of neurologic injury (e.g., coma) post cardiac arrest, and animal data suggesting that this can be ameliorated by hypothermia and two RCTs reported in 2002 • This has led to it to be recommended by many organizations including the AHA • Last year at this meeting I indicated that the evidence supporting its use post OOH CA associated with shockable rhythm's thought to be due to cardiac disease was weak.. • And that the evidence supporting its use following cardiac arrest associated with non-shockable rhythms, and following in-hospital cardiac arrest was even weaker. • The later may be due to the possibility that these patients have sustained more severe neurologic injury which is not amenable benefit from TH as currently practice. Summary, continued • As I have just reviewed – In the past year no new evidence has appeared supporting the use of TH for any indication – If anything, new studies have reinforced the skepticism I expressed last year, and others are voicing similar concerns. Summary (continued) • Based upon data I presented last year and new information which has become available during this past year, and until more definitive information becomes available, I recommend: – TH following out-of-hospital cardiac arrest TH should be limited to patients meeting the strict criteria of the original RCTs (witnessed, presenting with shockable rhythms, and thought to be of cardiac origin) – TH following in-hospital cardiac arrest TH should be limited to patients with the best likelihood of benefit (witnessed, shockable rhythms*, due to a reversible cause, who are without severe pre-existing disease or impaired neurologic status. (Consider using the GO-FAR score) *Non-shockable rhythms could be considered if arrest occurred peri-operatively – And finally, Instead of cooling to 32-34o, we should instead simply strictly keep body temperature no higher than 37.0o for the 30 hours after decision to treat and below 37.5o until 72 or more hours post arrest. Questions and Comments?