CHSF 20022014 NHS Confed OBC session PM

Innovative contracting models to deliver integrated care

Robert Breedon, Wragge and Co

Michael Meredith, PwC

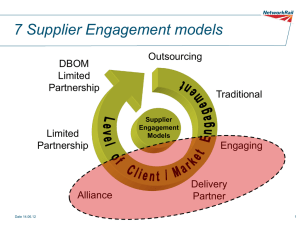

Alliance contracting

Key features

• The central assumption of alliance contracting is that organisations can achieve better outcomes

– particularly in the delivery of complex services – by working collaboratively within a single overarching contract.

• An alliance contract aligns incentives between these organisations through the construction of a common set of outcomes, encouraging collaboration to enable the delivery of coordinated services while sharing risk and accountability between alliance partners.

• This type of contract enables collaboration between distinct organisational entities; it is a means to deliver integrated services without the need for the development of integrated organisational forms.

• Specific pain/gain share mechanisms are pre-agreed by parties within the alliance and defined within the contract itself, yet are necessarily linked to overall contract outcomes; collective success leads to collective gain, and underperformance effects the whole alliance.

1

Alliance contracting to shift resources out of hospital

Case study 1: Alliance contracting in Canterbury, New Zealand

‘the first thing we do when there is a problem, and because this is an alliance, is ask

“How can we help? You are not performing. What’s the problem? Can anyone else in the alliance help?” And we put resources in. Because the idea of an alliance is that nobody fails. We either all fail or all succeed.’ - Carolyn Gullery, Canterbury Health Board

Alliance approaches have been used for a number of services areas in the Canterbury health system in New Zealand – including their acute demand management programme and its community rehabilitation and support service.

Results of the approach include:

• A shift in resources from acute hospital care towards community care and elective hospital services.

• More care being delivered by services outside the hospital – such as community based radiology, spirometry tests, more minor surgery performed in the community.

• Decreased acute admissions, readmissions and length of stay: among all major district health boards in New Zealand, Canterbury comes lowest for combined acute medical length of stay and acute readmissions.

• Lower levels of acuity are being more effectively managed in the community.

2

Prime provider model

Key features

• A single organisation is accountable for the delivery and coordination of a set of services and related outcomes defined by the commissioner.

• The prime provider is typically allocated a capitated budget to manage all care services for a specific population group (e.g. the frail elderly). This could even be for the care of a whole population within a defined geography (e.g. Alzira model in

Valencia

– case study 2).

• The prime provider is incentivised to coordinate services around the needs of those using them, invest in high value interventions, and ensure collaboration between providers involved in the delivery of the whole service. It is not expected that the accountable lead provider will provide all of the services.

• This contractual form shifts risk from the commissioner to accountable lead provider, who is responsible for achieving commissioner defined outcomes for the specified population within the allocated budget.

3

Delivering better outcomes at lower cost in Valencia

Case study 2: Alzira Model, Spain

Since 2003, the Alzira model in Valencia has used both capitation and outcome-based mechanisms to help the delivery of integrated and efficient health services to its population.

A single, integrated provider is responsible for all healthcare provided to the population of the region, receiving a fixed annual capitated budget.

Providers are measured against key outcomes (both clinical and patient experience), and profits of up to 7.5% within this model can be retained by the prime provider savings above this cap must be returned to the commissioner.

Improved clinical outcomes and high patient satisfaction, facilitated by closer integration of services and pathways.

Emergency waiting times in a cute setting of 60 minutes

– versus a wider regional average of 131.

The costs of providing health services to the commissioner have been reduced by

25%, with costs far lower than regionally and nationally.

4

Third sector as prime provider in Milton Keynes

Case study 3: COBIC in Milton Keynes

Milton Keynes was the first area to develop a COBIC in England, delivered initially for substance misuse services.

Milton Keynes PCT and Milton Keynes Local Authority worked in partnership to jointly develop an outcomes based approach to commissioning the substance misuse service.

They worked together to understand the outcomes that they wanted to see from the contract, working with both service users and partner agencies to do so. A contract was offered to providers which combined capitation and rewards for improved outcomes.

The contract was let to a third sector organisation, acting as prime contractor for the complete substance misuse service. The service itself was transformed extremely quickly, with improved outcomes for service users and financial savings for the commissioners.

The overall spend on the service was reduced by 20% in the first year as a result of the outcome based approach.

5

Financing and structuring: Key considerations

Services and population

Objectives and behaviours

Constraints

• Scope and outcomes

• Finances

• Interdependencies

• Collaboration and integration

• Early intervention and prevention

• Total system cost and investment

• System (e.g. PFI)

• Legislation (e.g. competition and choice)

• Stakeholder restrictions

Commercial options

• Incentives/payment

• Governance

• Investment and return mechanisms

6

Balancing risk and reward

• Allocated only where there is control and/or influence

• Has to be reasonable and proportionate

• Are you able to evidence your assumptions?

• Role of primary care is key

• Any provider has to report to their Board

7

Commercial considerations

• Market stimulation and development

• Providers involved in developing the solution early

• A reasonable contract term will be required to support investment

• Commissioning and governance arrangements will need to be clear (CCG/LA/LAT etc)

• Developmental approach

• Route to market

• Exit strategy

8

Legal and regulatory considerations

• NHS (Procurement, Patient Choice and Competition) Regulations 2103

Obligation to commission services from the most capable provider

Obliged to tender or not? Regulation 5

• NHS Standard Contract

Duration, Sub-contracting etc

Risk/reward options

Outcomes/Performance Indicators

Use in lead provider model/Alliances

• Competition Law

Avoid anti-competitive effects

If anti-competitive then demonstrate that benefits outweigh the anticompetitive effects (cost/benefit)

9

Thank you

This publication has been prepared for general guidance on matters of interest only, and does not constitute professional advice. You should not act upon the information contained in this publication without obtaining specific professional advice. No representation or warranty

(express or implied) is given as to the accuracy or completeness of the information contained in this publication, and, to the extent permitted by law, PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP, its members, employees and agents do not accept or assume any liability, responsibility or duty of care for any consequences of you or anyone else acting, or refraining to act, in reliance on the information contained in this publication or for any decision based on it.

© 2014 PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP. All rights reserved. In this document, “PwC” refers to

PricewaterhouseCoopers LLP (a limited liability partnership in the United Kingdom) which is a member firm of PricewaterhouseCoopers International Limited, each member firm of which is a separate legal entity.