20131024SGLT2Inh&CABG

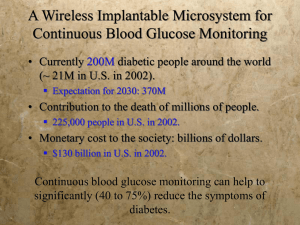

advertisement

Journal Club Abdul-Ghani MA, Defronzo RA, Norton L. Novel Hypothesis to Explain Why SGLT2 Inhibitors Inhibit Only 3050% of Filtered Glucose Load in Humans. Diabetes. 2013 Oct;62(10):3324-8. Abdallah MS, Wang K, Magnuson EA, Spertus JA, Farkouh ME, Fuster V, Cohen DJ; FREEDOM Trial Investigators. Quality of life after PCI vs CABG among patients with diabetes and multivessel coronary artery disease: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA. 2013 Oct 16;310(15):1581-90. 2013年10月24日 8:30-8:55 8階 医局 埼玉医科大学 総合医療センター 内分泌・糖尿病内科 Department of Endocrinology and Diabetes, Saitama Medical Center, Saitama Medical University 松田 昌文 Matsuda, Masafumi イプラグリフロジン:アステラス製薬(承認申請中) ルセオグリフロジン:大正製薬(フェーズⅢ) カナグリフロジン:田辺三菱製薬(フェーズⅢ、米国では承認) トホグリフロジン:サノフィ、中外製薬、興和(フェーズⅢ) エンパグリフロジン:ベーリンガー(フェーズⅢ) 2013年7月11日 Journal Club ダパグリフロジン:アストラゼネカ(フェーズⅢ) SGLT2阻害薬による研究は糖毒性のコンセプト解明に重要な役割を果たした! J. Clin. Invest. 79:1510-1515, 1987 By inhibiting glucose transport through the renal tubule, phlorizin normalizes plasma glucose without altering insulin secretion. J. Clin. Invest. Volume 79, May 1987, 1510-1515 Luseogliflozin FIG. 1. SGLT2 inhibitors in late-stage clinical trials. Based upon their PK/PD relationship, we postulate that their mechanism of action is related to secretion and/or active reabsorption in the proximal tubule and slow off rate from the SGLT2 target. Liu JJ, Lee T, DeFronzo RA.: Why Do SGLT2 inhibitors inhibit only 30-50% of renal glucose reabsorption in humans? Diabetes. 2012 Sep;61(9):2199-204. 2012年11月1日 Journal Club × × × × × ○ ○ ○ △ Diamant M, Morsink LM.: SGLT2 inhibitors for diabetes: turning symptoms into therapy. Lancet. 2013 Jul 11. doi:pii: S0140-6736(13)60902-2. 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)60902-2. [Epub ahead of print] 品名 製造元 剤形 開発段階 備考 ASP1941 一般名:イプラグリフロジン ipragliflozin アステラス製薬(株),寿製薬(株) TS-071 一般名:ルセオグリフロジン luseogliflozin 大正製薬(株),大正富山製薬(株),ノバルティスファーマ(株) TA-7284 一般名:カナグリフロジン canagliflozin 田辺三菱製薬(株),第一三共(株) INVOKANA™ BI10773 一般名:エンパグリフロジン empagliflozin 日本イーライリリー(株),日本ベーリンガーインゲルハイム(株) CSG452 TG7201 一般名:トホグリフロジン tofogliflozin サノフィ(株),興和(株) 経口薬 国内 (2013 年3 月11日申請) 申請中 BMS-512148 一般名:ダパグリフロジン dapagliflozin アストラゼネカ(株),ブリストル・マイヤーズ(株) Forxiga® 経口薬 国内 (2013 年3 月申請) 申請中 2012年11月EMA承認 米国 申請中 経口薬 国内 (2013 年4 月18日申請) 申請中 経口薬 国内 海外導出先:ヤンセンファーマ 申請中 シューティカルズ(米国) 2013/3/29FDA承認 (2013 年5 月27日申請) 経口薬 国内 (2013年10月申請) 申請中 2013/3/26 EMA申請 経口薬 国内 (2013 年6 月申請) 申請中 the Division of Diabetes, University of Texas Health Science Center at San Antonio, San Antonio, Texas. Diabetes 62:3324–3328, 2013 Inhibitors of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 (SGLT2) are a novel class of antidiabetes drugs, and members of this class are under various stages of clinical development for the management of type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM). It is widely accepted that SGLT2 is responsible for >80% of the reabsorption of the renal filtered glucose load. However, maximal doses of SGLT2 inhibitors fail to inhibit >50% of the filtered glucose load. Because the clinical efficacy of this group of drugs is entirely dependent on the amount of glucosuria produced, it is important to understand why SGLT2 inhibitors inhibit <50% of the filtered glucose load. In this Perspective, we provide a novel hypothesis that explains this apparent puzzle and discuss some of the clinical implications inherent in this hypothesis. FIG. 1. Renal glucose reabsorption in the proximal tubule in NGT individuals under physiologic conditions. FIG. 2. Relationship between glucose filtration load (GFL) and UGE and the plasma glucose concentration under physiologic conditions and during maximal inhibition of SGLT2. FIG. 3. Renal glucose reabsorption in the proximal tubule in NGT individuals under complete SGLT2 inhibition. FIG. 4. Predicted relationship between the fraction of filtered glucose excreted in the urine and the plasma glucose concentration during maximal inhibition of SGLT2. The maximal SGLT1 transport capacity was estimated at 120 g/day (see text for details). GFL, glucose filtration load. LX4211: Lexicon Pharmaceuticals, Princeton, NJ Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics (2012); 92 2, 158–169. FIG. 5. Predicted fold increase in the level of glucosuria produced by SGLT2 inhibitors in relation to the percent inhibition of SGLT1 activity. Vallon et al. (12) reported that in SGLT2 knockout mice, the fraction of filtered glucose excreted in the urine increased linearly with the increase in the amount of filtered glucose such that under hyperglycemic conditions, the fractional excretion of glucose can reach as high as 90%. This prediction is consistent with the results reported by Powell et al. (16) who demonstrated that SGLT2 knockout mice manifest glucosuria which equals ;30% of filtered glucose. However, breeding SGLT2 knockout mice with mice lacking SGLT1 to create the double (SGLT1 and SGLT2) knockout mouse resulted in a threefold greater glucosuric effect compared with that observed in the SGLT2 knockout mouse (747 vs. 224 mg/day). Of note, mice lacking only SGLT1 manifested only a small, nonsignificant amount of glucosuria (,15 mg/day). In mice with deletion of SGLT2, e.g., SGLT2 knockout mice, there is an ;30% decrease in SGLT1 expression. Renal excretion of glucose in Sglt2−/− is a function of the amounts of glucose filtered: Clearance studies under anesthesia (n = 9 to 10 per group). Vallon V et al. JASN 2011;22:104-112 ©2011 by American Society of Nephrology Twenty-four-hour urinary glucose excretion (UGE) of Sglt1 KO, Sglt2 KO, double-KO (DKO), and WT littermate mice. Powell D R et al. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab 2013;304:E117-E130 ©2013 by American Physiological Society In summary, why do SGLT2 inhibitors produce UGE, which is ,50% of the filtered glucose load? It is simply because they are specific SGLT2 inhibitors. Under physiologic conditions, SGLT1 operates at submaximal transport capacity. Complete inhibition of SGLT2 forces SGLT1 to reabsorb glucose in full capacity, and therefore, only the fraction of filtered glucose that escapes SGLT1 will be excreted in the urine. Thus, we anticipate that future SGLT2 inhibitors with the ability to partially inhibit SGLT1 will produce more robust glucosuria compared with highly specific SGLT2 inhibitors. Message 2012年のDiabetes誌(2012 61(9):2199-204)では近位尿 細管のSGLT2阻害の様式によるのではないかと言ってい たが、今回は血糖が正常~低くなるとSGLT1が働くせい ではないかと話が変わっている。 LX4211がよいかもしれないとか、Canagliflozinがよい かもしれないというようなことなのか? 閾値からは低 血糖は起きにくいはずなので、効果優先となると今後、 更に血糖管理が容易となるかもしれない。ただし、腸管 やほかの組織のSGLT1や組織によっては発ガン性が今後 の課題かもしれない。ちなみにLX4211はすでに臨床デー タも出ておりLexicon社はTEXASに会社があったりする。 ともかく、日本でもSGLT2阻害薬は来年には発売とな る! the Bypass Angioplasty Revascularization Investigation 2 Diabetes (BARI 2D) Study Group Robert L. Frye, M.D., Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN; Phyllis August, M.D., M.P.H., New York Hospital Queens, Queens, NY; Maria Mori Brooks, Ph.D., Regina M. Hardison, M.S., Sheryl F. Kelsey, Ph.D., Joan M. MacGregor, M.S., and Trevor J. Orchard, M.B., B.Ch., University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh; Bernard R. Chaitman, M.D., Saint Louis University, St. Louis; Saul M. Genuth, M.D., Case Western Reserve University, Cleveland; Suzanne H. Goldberg, R.N., M.S.N., National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, MD; Mark A. Hlatky, M.D., Stanford University, Palo Alto, CA; Teresa L.Z. Jones, M.D., National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Bethesda, MD; Mark E. Molitch, M.D., Feinberg School of Medicine, Northwestern University, Chicago; Richard W. Nesto, M.D., Lahey Clinic Medical Center, Burlington, MA; Edward Y. Sako, M.D., Ph.D., University of Texas Health Science Center, San Antonio; and Burton E. Sobel, M.D., University of Vermont, Burlington Reviewed on June 11, 2009 N Engl J Med. 2009 Jun 11;360(24):2503-15 N Engl J Med. 2009 Jun 11;360(24):2503-15 Mount Sinai School of Medicine (M.E.F., M.D., G.D., J.W., S.B., V.F.), the Cardiovascular Research Foundation (G.D.), and New York Presbyterian Medical Center (C.R.S.) — all in New York; Peter Munk Cardiac Centre and Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, University of Toronto, Toronto (M.E.F.), and the University of British Columbia, Vancouver (K.R.) — both in Canada; New England Research Institutes, Watertown, MA (L.A.S., F.S.S., M.Y., V.M.); the Cardiovascular Division, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston (S.D.S., A.S.D.); Baylor University Medical Center, Dallas (M.M.); St. Luke’s Mid-America Heart Institute, University of Missouri–Kansas City, Kansas City (D.J.C., E.A.M.); the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute, Bethesda, MD (Y.R., R.B.); Mayo Clinic, Rochester, MN (B.J.G.); Yale University, New Haven, CT (A.L.); Dante Pazzanese Hospital (J.E.S.) and the Heart Institute InCor, University of S.o Paulo Medical School (W.H.) — both in S.o Paulo; Royal Perth Hospital, Perth, Australia (J.R.); All India Institute of Medical Sciences, New Delhi (B.B.); University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill (J.B.); St. Joseph’s Hospital, Atlanta (S.K.); University of Lille, Lille, France (M.B.); and Centro Nacional de Investigaciones Cardiovasculares, Madrid (V.F.). N Engl J Med 2012;367:2375-84. Saint Luke’s Mid America Heart Institute, Kansas City, Missouri (Abdallah,Wang,Magnuson, Spertus, Cohen); University of Missouri-Kansas City School of Medicine, Kansas City (Abdallah, Magnuson, Spertus, Cohen); Mount Sinai School of Medicine, New York, New York (Farkouh, Fuster); Peter Munk Cardiac Centre and Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, University of Toronto, Toronto, Ontario, Canada (Farkouh). JAMA. 2013;310(15):1581-1590. IMPORTANCE The FREEDOM trial demonstrated that among patients with diabetes mellitus and multivessel coronary artery disease, coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) surgery resulted in lower rates of death and myocardial infarction but a higher risk of stroke when compared with percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) using drug-eluting stents. Whether there are treatment differences in health status, as assessed from the patient’s perspective, is unknown. OBJECTIVES To compare the relative effects of CABG vs PCI using drug-eluting stents on health status among patients with diabetes mellitus and multivessel coronary artery disease. DESIGN, SETTING, AND PARTICIPANTS Between 2005 and 2010, 1900 patients from 18 countries with diabetes mellitus and multivessel coronary artery disease were randomized to undergo either CABG surgery (n = 947) or PCI (n = 953) as an initial treatment strategy. Of these, a total of 1880 patients had baseline health status assessed (935 CABG, 945 PCI) and comprised the primary analytic sample. INTERVENTIONS Initial revascularization with CABG surgery or PCI. MAIN OUTCOMES AND MEASURES Health status was assessed using the angina frequency, physical limitations, and quality-of-life domains of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire at baseline, at 1, 6, and 12 months, and annually thereafter. For each scale, scores range from 0 to 100 with higher scores representing better health. The effect of CABG surgery vs PCI was evaluated using longitudinal mixed-effect models. CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; CHF, congestive heart failure; COPD, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; RDS, Rose Dyspnea Scale; SAQ, Seattle Angina Questionnaire. a Data are reported as No. (%) unless otherwise indicated. b Denominators may not match for some variables due to missing baseline data. c Scores on the SAQ scale (reported by increments of 10) range from 0 to 100 with higher scores indicating better quality of life. Zero indicates daily angina or nitroglycerin use, severely limited physical activity due to cardiac disease, or severely affected quality of life for each domain. A score of 100 indicates no limitations on the same subscales. d RDS scores range from 0 to 4 with higher scores indicating increased dyspnearelated limitations (0, no dyspnea with activities; 4, dyspnea occurs with minimal physical activity like getting dressed). Spertus JA, Winder JA, Dewhurst TA, Deyo RA, Prodzinski J, McDonell M, Fihn SD.: Development and evaluation of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire: a new functional status measure for coronary artery disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1995 Feb;25(2):333-41. Rose GA, Blackburn H. Cardiovascular survey Methods. Geneva, World Health Organization, 1968. Figure 2. Seattle Angina Questionnaire Results Mean scores are reported (error bars indicate 95%CIs) for the angina frequency, physical limitation, and quality-of-life subscales of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ). Scores for each subscale range from 0 to 100 (reported by increments of 10) with higher scores representing better health status or quality of life. Table 2. Mean Effect of CABG and PCI on Disease-Specific Health Status According to Longitudinal Models Adjusted for Baseline Abbreviations: CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SAQ, Seattle Angina Questionnaire. a Positive values indicate better quality of life with CABG. Frequency of angina by treatment group according to the Seattle Angina Questionnaire (SAQ)– angina frequency scale. Categories (with scores by increments of 10) were defined as no angina (score, 100), monthly angina (score, 70-90), weekly angina (score, 40-60), or daily angina (score, <40). See eTable 4 in the Supplement for exact data and numbers of patients. P value comparisons were determined using ordinal logistic regression. Data are reported according to the Rose Dyspnea Scale (RDS; range, 0-4; higher scores represent more dyspnea). P value comparisons were determined using ordinal logistic regression. See eTable 6 in the Supplement for exact data. Figure 5. Subgroup Analysis of the Mean Treatment Effect of CABG vs PCI on the SAQ–Angina Frequency Subscale All subgroup counts are based on the baseline patient assessment. Treatment effects at 12 months, 24 months, associated 95%CIs, and interaction P values were derived from longitudinal randomeffect growth-curve models. CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; LAD, left anterior descending artery; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SAQ, Seattle Angina Questionnaire. Figure 5. Subgroup Analysis of the Mean Treatment Effect of CABG vs PCI on the SAQ–Angina Frequency Subscale All subgroup counts are based on the baseline patient assessment. Treatment effects at 12 months, 24 months, associated 95%CIs, and interaction P values were derived from longitudinal randomeffect growth-curve models. CABG, coronary artery bypass graft; LAD, left anterior descending artery; PCI, percutaneous coronary intervention; SAQ, Seattle Angina Questionnaire. RESULTS At baseline, mean (SD) scores for the angina frequency, physical limitations, and quality-oflife subscales of the Seattle Angina Questionnaire were 70.9 (25.1), 67.3 (24.4), and 47.8 (25.0) for the CABG group and 71.4 (24.7), 69.9 (23.2), and 49.2 (25.7) for the PCI group, respectively. At 2-year followup, mean (SD) scores were 96.0 (11.9), 87.8 (18.7), and 82.2 (18.9) after CABG and 94.7 (14.3), 86.0 (19.3), and 80.4 (19.6) after PCI, with significantly greater benefit of CABG on each domain (mean treatment benefit, 1.3 [95%CI, 0.3-2.2], 4.4 [95%CI, 2.7-6.1], and 2.2 [95%CI, 0.7-3.8] points, respectively; P < .01 for each comparison). Beyond 2 years, the 2 revascularization strategies provided generally similar patient-reported outcomes. CONCLUSIONS AND RELEVANCE For patients with diabetes and multivessel CAD, CABG surgery provided slightly better intermediate-term health status and quality of life than PCI using drug-eluting stents. The magnitude of benefit was small, without consistent differences beyond 2 years, in part due to the higher rate of repeat revascularization with PCI. TRIAL REGISTRATION clinicaltrials.gov Identifier: NCT00086450 Message 糖尿病で多枝冠動脈疾患(CAD)を有する患 者1880人を対象に、冠動脈バイパス術 (CABG)の有害転帰リスクが経皮的冠動脈 インターベンション(PCI)より低いとした FREEDOM試験を解析。 2年後のシアトル狭心症質問票(SAQ)の狭 心症頻度や生活の質(QOL)などの患者報告 によるスコアは、CABG群が有意に高かった (P<0.01)。 QOLからもCABGがよい!