slides

advertisement

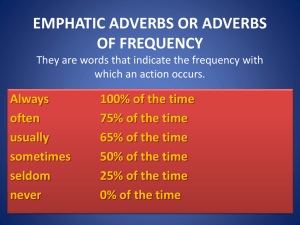

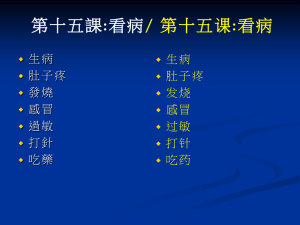

Saying nothing: Frequency effects in Dominican Spanish null subjects Cristina Martinez Sanz (U of Ottawa) & Gerard Van Herk (Memorial U) The spark: • “every aspect of language can profitably be re-examined in light of the important frequency effects” (Bybee 2002) • …but most work so far is on phonology For example… • intervocalic /d/ (Bybee, 2002; Díaz-Campos & Gradoville, 2011) • coronal stop deletion (Bayley & Loudermilk, 2008; Bybee 2001, 2002; Walker 2012) • lenition of Spanish syllable final /r/ (DíazCampos, 2005, 2006) • syllable final /s/ (Brown, 2009; Fife-Muriel, 2009) • Some studies find frequency effects, some don’t • But, very little work on frequency effects in syntax Today’s variable • Null subject in Spanish, aka “subject personal pronoun” (SPP) variation • For example: yo/0 te voy a hacer una historia buena ‘I’m going to tell you a good story’ A widely studied variable… • …but not with respect to frequency Dialectal differences • Factor groups: stable across dialects • Factor group rankings: -Person is the first ranked factor group in Caribbean dialects, whereas it is overriden by discourserelated constraints (switch reference) in nonCaribbean dialects (Otheguy et al. 2007, Orozco & Guy 2008, Martínez Sanz 2011). Frequency effects • Erker & Guy (2012) look at Mexican and Dominican Spanish speakers in New York City • 12 informants, 4916 tokens • “Frequent” forms (N=13; each form that makes up more than 1% of the token file (N=1,120) • Frequency has no direct role, but it influences whether other factors play a role (activation) and/or how much (amplification) E&G’s findings • Activated: morphological regularity, semantic class, person/number • Amplified: TMA, switch reference Theoretical assumption • Speakers need a certain level of familiarity with a form to figure out the probabilistic constraints on variant choice in that context – It’s an exemplar thing Bayley (2013) • Mexican Spanish speakers in Texas, California • 29 informants, 8676 tokens • Tested E&G, threw in a couple more factor groups • 19 frequent forms (N=2612) Bayley’s findings • Amplified: Semantic class (like E&G) • Weakened: TMA, switch reference, person/number, lexical aspect (opposite of E&G) • So frequency doesn’t activate or amplify constraints in this data set, contrary to what Erker & Guy (2012) predict • Frequency does have a (weak) independent effect, given a large enough data set Why replicate again? • Maybe we can resolve these differences • We have access to non-contact data – And contact with English might account for the wonkiness of E&G and Bayley’s findings • We have access to Dominican Spanish data – This variety is famously variable, with higher rates of overt subjects than elsewhere – And in more contexts (Martínez Sanz 2011) The data • 25 interviews, 2008, Dominican Republic Data extraction • 34 speakers • First 200 tokens per speaker • 4567 tokens – after exclusions, other variants, etc. • 835 frequent-form tokens Frequent verb forms Verb form N % corpus % null subject tengo (I have) 106 2.32 46.23 tenía (I had) 105 2.30 30.48 es (s/he is) 93 2.04 48.39 voy (I go) 93 2.04 36.56 estaba (I was) 80 1.75 28.75 iba (s/he used to go) 67 1.47 47.76 fui (I went) 61 1.33 44.26 sé (I know) 61 1.33 26.23 era (s/he was) 60 1.31 41.67 digo (I say) 55 1.20 47.27 dije (I said) 55 1.20 41.82 Other (linguistic) constraints • Switch reference – Bayley & Pease-Alvarez 1996, 1997; Bayley et al. 2012; Cameron 1995, 1996; Flores-Ferrán 2004; Otheguy & Zentella 2012; SilvaCorvalán 1994 • Person/number – Bayley & Pease-Alvarez 1996, 1997; Cameron 1992, 1996; Erker & Guy 2012; Flores-Ferrán 2004; Otheguy et al. 2007; Otheguy & Zentella 2012 • Tense/mood/aspect – Silva-Corvalán 1994; Bayley & Pease-Alvarez 1997; Bayley et al. 2012 • Ambiguity re person – Hochberg 1986; Cameron 1993 • Verb semantics – Travis 2007 Interactions • Previous studies have coded for different things • But many of these overlap – TMA and form ambiguity – Semantic features and lexical aspect – In Bayley, subject type and stativity interact with frequency Factor groups coded • Person/number of the subject – 1/2/3, singular/plural, plus 2nd indefinite • TMA of the verb (~ambiguity) – Preterit, present & related, other • Semantic features of the verb (~lexical aspect) • Reference – Same or switch • Form frequency – Tengo and tiene are different forms Findings • (See also table in handout!) • Note that null subject is the application value Subject Type (Person/Number) All data Frequent forms Infrequent forms First plural (nosotros/as) .82 No data .81 Second + third plural (ellos/as/ustedes) Third singular (el/ella/usted/uno) .82 No data .81 .51 .66 .48 First singular (yo) .39 .44 .37 Second singular non-specific (tu/usted) Second singular specific (tu/usted) .19 No data .19 .12 No data .11 RANGE 70 20 70 Verb TMA (Ambiguity) All data Preterit and indefinite Present (and future and similar) Imperfect, conditional, subjunctive RANGE Frequent forms Infrequent forms .61 .52 .61 .47 .54 .45 .46 .44 .46 15 10 15 Verb semantics (Lexical Aspect) All data Frequent forms Infrequent forms Speech act .55 .63 .54 Motion .52 .57 .52 Other .51 .46 .52 Copula .48 .44 .47 Psychological .38 .56 .39 Perception .32 .43 .32 RANGE 23 20 22 Switch Reference All data Frequent forms Infrequent forms Same referent .60 .60 .61 Switch referent .38 .37 .38 RANGE 22 23 23 All tokens together • All usual factor groups are significant – Direction virtually identical to earlier (Caribbean Spanish) studies • Frequency is not significant – i.e., higher-frequency items are not more or less likely to have null subjects – As in E&G and Bayley (more or less) Infrequent verb forms • Behave almost exactly like the full data set • Because they are the full data set, more or less! Frequent verb forms • Same effects as full data set, very slightly weaker • One difference: Person/Number: – Because there were no frequent forms in plurals or second person, and those were the strongest constraints in the full data set – Similar effects in Bayley, Erker & Guy Frequent verb forms • TMA (Ambiguity) -Very slightly weaker effects • Verb semantics (Lexical aspect) -very slightly stronger effects • Switch reference -No differences So… • Frequency alone doesn’t matter – …although for this variable, nobody has said that it should • Frequency doesn’t amplify or activate any other constraints Three studies, three different findings • Why? 1. Speech community differences • Dialect differences – Mexican Spanish has less productive overt subject pronoun system • Contact – Previous studies were based on Spanish speakers in contact with English – Their constraint systems might be eroded in infrequent contexts (a Nancy Dorian thing) 2. Data collection differences: Is this all lexically driven? • If frequency is determined based on the corpus, topic and interlocutors could affect which verb forms are frequent. • The Bayley interviews are about language choices, so verba dicendi are frequent • What’s the theoretical justification for this method? Surely what matters is which forms are frequent in a speaker’s cognitive system 3. Similarities across corpora: are we measuring frequency wrong? • Even if frequent forms vary from corpus to corpus, a number of forms appear in all three corpora. • In the three data sets, most frequent forms are in the first and third person singular, and they include a lot of statives, which trigger overt subject insertion. Further research: redefining frequency • Person -Should we look at different Persons separately, given that they have very different properties? • Verb Forms and Verb Types -Frequent verb forms include verbs that bear very different properties. -Should we look at how frequency affects verb types, not just verb forms? Further research: redefining frequency • Frequency might not work the same in phonology (where most frequency work has been carried out) as in syntax. • Given the conflicting results in SPP frequency studies, we might want to explore different ways of measuring frequency in syntax (by lemma, form, collocation?) Conclusion • Maybe there’s no frequency effect • Maybe there is, but we haven’t yet figured out how to find it Thanks • Bob Bayley (and indirectly Greg Guy and Danny Erker), for sharing work in progress • The people in the Dominican who shared their language with Cristina Contact us • Gerard: gvanherk@mun.ca • Cristina: cristina.martinez.sanz@gmail.com