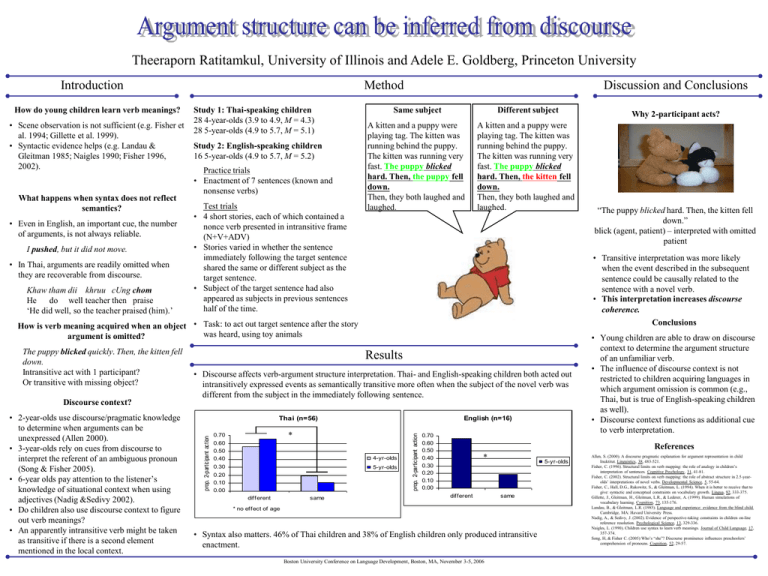

Argument structure can be inferred from discourse.

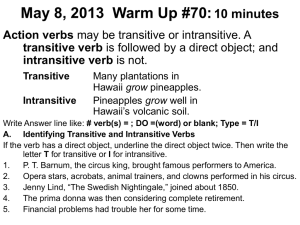

advertisement

Theeraporn Ratitamkul, University of Illinois and Adele E. Goldberg, Princeton University Introduction How do young children learn verb meanings? • Scene observation is not sufficient (e.g. Fisher et al. 1994; Gillette et al. 1999). • Syntactic evidence helps (e.g. Landau & Gleitman 1985; Naigles 1990; Fisher 1996, 2002). What happens when syntax does not reflect semantics? • Even in English, an important cue, the number of arguments, is not always reliable. I pushed, but it did not move. • In Thai, arguments are readily omitted when they are recoverable from discourse. Khaw tham dii khruu cUng chom He do well teacher then praise ‘He did well, so the teacher praised (him).’ Method Study 1: Thai-speaking children 28 4-year-olds (3.9 to 4.9, M = 4.3) 28 5-year-olds (4.9 to 5.7, M = 5.1) Study 2: English-speaking children 16 5-year-olds (4.9 to 5.7, M = 5.2) Practice trials • Enactment of 7 sentences (known and nonsense verbs) Test trials • 4 short stories, each of which contained a nonce verb presented in intransitive frame (N+V+ADV) • Stories varied in whether the sentence immediately following the target sentence shared the same or different subject as the target sentence. • Subject of the target sentence had also appeared as subjects in previous sentences half of the time. Discussion and Conclusions Same subject Different subject A kitten and a puppy were playing tag. The kitten was running behind the puppy. The kitten was running very fast. The puppy blicked hard. Then, the puppy fell down. Then, they both laughed and laughed. A kitten and a puppy were playing tag. The kitten was running behind the puppy. The kitten was running very fast. The puppy blicked hard. Then, the kitten fell down. Then, they both laughed and laughed. • Discourse affects verb-argument structure interpretation. Thai- and English-speaking children both acted out intransitively expressed events as semantically transitive more often when the subject of the novel verb was different from the subject in the immediately following sentence. English (n=16) Thai (n=56) * 0.70 0.60 0.50 0.40 4-yr-olds 0.30 5-yr-olds 0.20 0.10 0.00 different same prop. 2-participant action • 2-year-olds use discourse/pragmatic knowledge to determine when arguments can be unexpressed (Allen 2000). • 3-year-olds rely on cues from discourse to interpret the referent of an ambiguous pronoun (Song & Fisher 2005). • 6-year olds pay attention to the listener’s knowledge of situational context when using adjectives (Nadig &Sedivy 2002). • Do children also use discourse context to figure out verb meanings? • An apparently intransitive verb might be taken as transitive if there is a second element mentioned in the local context. Results prop. 2-partic ipant action Discourse context? “The puppy blicked hard. Then, the kitten fell down.” blick (agent, patient) – interpreted with omitted patient • Transitive interpretation was more likely when the event described in the subsequent sentence could be causally related to the sentence with a novel verb. • This interpretation increases discourse coherence. Conclusions How is verb meaning acquired when an object • Task: to act out target sentence after the story was heard, using toy animals argument is omitted? The puppy blicked quickly. Then, the kitten fell down. Intransitive act with 1 participant? Or transitive with missing object? Why 2-participant acts? 0.70 0.60 0.50 0.40 0.30 0.20 0.10 0.00 • Young children are able to draw on discourse context to determine the argument structure of an unfamiliar verb. • The influence of discourse context is not restricted to children acquiring languages in which argument omission is common (e.g., Thai, but is true of English-speaking children as well). • Discourse context functions as additional cue to verb interpretation. References * different 5-yr-olds same * no effect of age • Syntax also matters. 46% of Thai children and 38% of English children only produced intransitive enactment. Boston University Conference on Language Development, Boston, MA, November 3-5, 2006 Allen, S. (2000). A discourse pragmatic explanation for argument representation in child Inuktitut. Linguistics, 38, 483-521. Fisher, C. (1996). Structural limits on verb mapping: the role of analogy in children’s interpretation of sentences. Cognitive Psychology, 31, 41-81. Fisher, C. (2002). Structural limits on verb mapping: the role of abstract structure in 2.5-yearolds’ interpretations of novel verbs. Developmental Science, 5, 55-64. Fisher, C., Hall, D.G., Rakowitz, S., & Gleitman, L. (1994). When it is better to receive that to give: syntactic and conceptual constraints on vocabulary growth. Lingua, 92, 333-375. Gillette, J., Gleitman, H., Gleitman, L.R., & Lederer, A. (1999). Human simulations of vocabulary learning. Cognition, 73, 135-176. Landau, B., & Gleitman, L.R. (1985). Language and experience: evidence from the blind child. Cambridge, MA: Havard University Press. Nadig, A., & Sedivy, J. (2002). Evidence of perspective-taking constraints in children on-line reference resolution. Psychological Science, 13, 329-336. Naigles, L. (1990). Children use syntax to learn verb meanings. Journal of Child Language, 17, 357-374. Song, H, & Fisher C. (2005) Who’s “she”? Discourse prominence influences preschoolers’ comprehension of pronouns. Cognition, 52, 29-57.