Experiments

advertisement

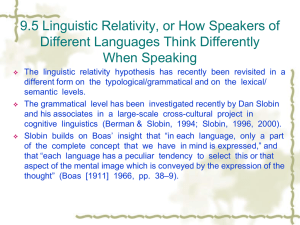

Language and thought Relationship of cognition and language • Categories of cognition are shaped by language – Sapir and Whorf’s linguistic relativity • Cognitive categories develop independently of language both in evolution and in ontogeny, language only builds upon these – Piaget: cognitive development leads language development • Language and cognition are independent – Chomsky • Cognition follows its own path, but language modulates its categories Early experiments 1. language = thought Behaviorism • Watson, 1913: thought = subvocal speech 2. language ≠ thought • Smith et al., 1947: curare experiment: muscle relaxant Political correctness “language use has an effect on the way we think” • euphemisms in politics – Pacification/pacifikáció = bombázás – Revenue increase/bevételnövelés = adó – Rationalisation/munkaerő-gazdálkodás = elbocsátások • social movements: sexist/racist etc. language is responsible for sexist/racist etc. thinking – chairman → chairperson – Gypsy → Roma (?) – blind → with visual impairment • Orwell, 1984: Newspeak Language shapes the mind • linguistic determinism: a language shapes psychological mechanisms • Benjamin Lee Whorf • Language shapes the mind, world view, structure of science • Differences in lexical (vocabulary) and grammatical organization result in different conceptual schemes Whorf: linguistic determinism and relativity • Linguist and engineer, student of anthropologist Edward Sapir – Studied native American cultures and languages – Emphasized the variety and differences of cultures, not the common features • Strong view: all higher forms of thought build on language • Weak view: the structure of the language one generally uses influences the way they understand their environment and act upon in it Linguistic relativity (the Sapir-Whorf Hypothesis) • Follows from linguistic determinism • Linguistic relativity: distinctions encoded in one language are unique to that language alone, and "there is no limit to the structural diversity of languages” – It is impossible to translate precisely from one language to another • lexical and grammatical relativity Lexical influences • Lexical level: what words are found in a given language, and what they refer to – different languages carve up the world in different ways through more or less specialized vocabularies – languages differ with respect to how they divide up the world into nouns and verbs • lightning: a N in English, but a V in Hopi – duration an important feature • Tzotzil Mayan: eat-mushy; eat-a-slender-shape-food, eatmeat – the properties of objects are incorporated into the verbs Grammatical influences on thinking • Number category – whether inanimate nouns can be pluralized or not – in English any noun can be pluralized as long as the referent is discrete, i.e., mass nouns such as paper, flour cannot be pluralized • count nouns such as pen, girl – in Yucatec, only animate nouns can be pluralized – Lucy (1992): English speakers specify the number of objects in descriptions of line drawings more frequently than Yucatec speakers Grammatical influences • Tense markers – determine location of events in time • past ---------- now ---------- future – he is running – he ran – he will run WARI in Hopi • How does a temporal language compare to a “timeless language”? Tense • Hopi distinguishes between – Reportive: report of a recent or ongoing event – Expective: report of an expected event (past or future) – Nomic (not described) • According to Whorf these are not tenses because they reflect the epistemic validity of the statement rather than its duration or location in time Potawatomi inclusive and exclusive pronouns: we (www.potawatomilang.org) Hungarian object agreement • The verb form signals the specificity of the object – Megevett egy almát. – Megette az almát. Hungarian locatives Static Goal Source Interior (3D) BAN BA BÓL Exterior (2D) N RA RÓL HOZ TÓL Approximate NÁL (dimension neutral) Examples 1. 2. 3. 4. snow colours gender spatial language Snow Eskimos have many different words for ‘snow’ → evidence that they see snow differently (urban legend!) → Boas, (1911): 4 • • • • aput („snow on the ground”) gana („falling snow”) piqsirpoq („drifting snow”) qimuqsuq („a snowdrift”) → Sapir& Whorf, 1940: 7 → 1978: 50 → 1984 (New York Times): 100 The truth about snow • There are several Eskimo languages + Eskimo languages differ in the number of expressions they have for snow • Definition of “word” is problematic – Inuit is a polysynthetic language: are words derived from the same stem different or not? • More importantly • Even if it was true that one language had more, is it evidence that they see snow differently? painters: paints ornithologists: birds Colors Basic colour terms (Berlin & Kay, 1969) • Properties – – – – 1 morpheme Not restricted to one class of items (e.g. blond) Do not belong to the scope of another color terms (e.g. torqoise) Frequently and generally used • Basic color terms are chosen from 11 colors by all languges: black, white, red, yellow, green, blue, brown, pink, purple, orange, grey. • languages differ in how many basic color terms they have (Hungarian for ‘pink’ rózsaszín is not a basic color term) • 2 colour terms (mili-mola): Dani, New Guinea • There seems to be a universal hierarchy of colour categorisation. black white red green yellow blue brown purple pink orange grey Do speakers of different languages see colors differently? • Color categories are not arbitrary! • Same everywhere: – light – Operation of the human eye • 3 kinds of cones in color perception → these determine what we see • Experiments (pl. Heider, 1972 – the dani): recalling and discrimination is good for colors—focal colors Experimental results (pl. Heider & Oliver, 1972; Rosch, 1978, Berlin & Kay 1969, Kay & Kempton 1984) • People speaking different languages choose the same shade as best exemplars of a category (focal colours) – The best exemplar of grue in grue languages is the same as the best exemplar of green in green-blue languages • Dani do as well as English speakers in non/verbal colour discrimination and memory tasks • In a free categorization task, different speakers use different categories (those marked in their languages) Winawer et al 2007 • English and Russian speakers – Russian: dark blue/light blue distinction • A blue shade shown, then two blue shades • Task: which of the two is the same shade as the probe? • Russian speakers: faster RT if the two shades are from different linguistic colour categories Gilbert et al 2006 • If language affects perception, the effect should be stronger for the right visual field • Task: Which side is the different shade on? • Variables: – shade difference across or within linguistic category (blue-green) – Target in left or right visual field • Results: when different linguistic categories, faster response in RVF Korean locatives (Bowerman & Choi 1994, 2001) Korean locatives (Bowerman, 1996) • Korean (vs. English and Hungarian): no linguistic distinction, between placing an object in a container or on a surface (in vs. on, -ban vs. -on) • Korean language distinguishes between tight fit (ring on a finger, picture on the wall) and loose fit (fruit in a bowl, object leaning against a wall) – This distinction holds for both containment (in) and support (on) • Experiments – English/Korean babies differentiate all potential spatial distinctions – As a results of acquiring a language certain spatial distinctions (those strengthened by language) become salient in representation Navajo shape classifiers • Carroll and Casagrande: Navajo vs. English – Navajo verbs change form according to the shape of the object it takes (shape classifiers) • flexible vs. rigid; flat vs. round – give blue rope and yellow stick and ask which of the two a blue stick can go with • Navajo choose shape: yellow stick – English choose color: blue rope – conducted the test with upper class Bostonians • responded like Navajo children – there is other kinds of determinism than just linguistic determinism Grammatical gender and object perception Experiment(Boroditsky & Schmidt, 2003) – Spanish, German and English speakers (experiment language: English) – Training: 24 pairs of object - name apple – Paul / Paula bench – Eric / Erica clock – Karl / Karla – Test: object word shown, name has to be recalled apple – ? bench – ? clock – ? Results – For Spanish and German speakers, better recall performance for pairs where the gender of the name corresponds to the gender of the object word Spatial reference (Brown 2001) • Ego-centric (left, right, in front of me, behind me) – relative • Intrinsic (left of the object, in front of the object, etc) • Geocentric (hill-wise, sea-wise, etc) – absolute Relative right back left front Intrinsic back right left front Absolute West South North East Tzeltal • Left „xin” and right „wa’el” – Refer to body parts only • Absolute reference system: – „alan”: downhill ~North – „ajk’ol”: uphill ~South – Indoors, outdoors Experiments • Dutch + Tzeltal speakers (Bowerman, Levinson) – – Seated at talble in a room, shown a pattern Turned 180 degrees, asked to reproduce pattern Chips task Chips task - results Maze task Maze - results Evidence for Relativity? • Li & Gleitman (2002) – Response depends on environment: the availability of reference points • Compare cities/varied landscape vs. open landscape – In a darkened room (no visible reference points), English speakers also use the absolute reference frame Reference frames and ecological conditions