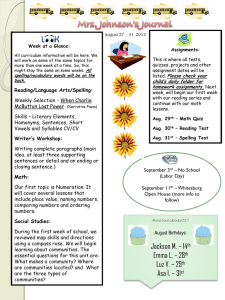

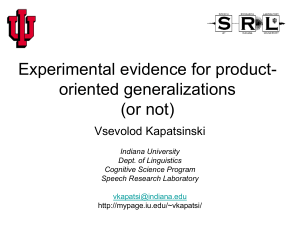

Stochastic competition in the grammar and the primacy of the lexicon

advertisement

Regularity is overrated: Stochastic competition in grammar and the primacy of the lexicon

Vsevolod Kapatsinski

Department of Linguistics, University of Oregon

Introduction

Velar palatalization in Pseudo-Russian:

Replicating the effect in the lab (Kapatsinski

Regular system: for every input, the grammar produces only one

output

Experimental data

A classroom dictation task. Graded. Non-speeded.

Subjects should retrieve the rule if they know it.

Subjects are college students, extensively trained on the rule.

No errors for raz- but at chance for bez- with unknown words:

2010a)

Native English speakers

Ways to achieve regularity

•Minimize competition between generalizations

Restricting structural description of rules so that no rules

compete for the same input

•Resolve competition in a winner-take-all manner

Strict ranking in Optimality Theory

The relevant grammar

Same examples of palatalization

Exposed to one of the following languages:

Don’t spell ‘z’

A stem should have

a constant spelling

More support for nonpalatalizing rule in LgII

Linguistic description: Maximizing regularity

This paper: Some cases where speakers do not

Should see less velar

palatalization in LgII if

the rule is overgeneral

(applies to velars) and

if the competition with

the palatalizing rule

is resolved stochastically

since the palatalizing rule

is stronger in both

languages

Case I: Velar palatalization in Russian

(Kapatsinski 2010a)

Spell what you hear

A phoneme should have

a constant spelling

Result

*

Rule: {k;g}{tᶘ;ᶚ}/_-itj

Summary of Case II

Adjectival inflection is regular whole wordforms need not be stored

Masculine singular

forms predictable

given stress

The preposition bez (always spelled with ‘z’)

Native lexicon: No exceptions

Nonce borrowings (web data):

Palatalization fails often

Summary of Case I

(e.g., to book bukitj)

A linguistic description of the morphophonology of velar palatalization

has rules that are too specific compared to what the learners acquire

Why?

Hypothesis: Russian speakers acquire an “overly”-general rule “just add –itj”

that competes with {k;g}{tᶘ;ᶚ}itj

The more –itj attaches to non-velars, the more reliable “just add –itj” will be.

Thus the more likely it will be to outcompete {k;g}{tᶘ;ᶚ}itj

if competition is resolved stochastically.

Prediction: palatalization should fail in front of suffixes that often attach to stems

that end in consonants that are ineligible for palatalization

Crucial test case: Masculine diminutives

Three suffixes: -ik, -ok, -ek.

In the native lexicon, palatalization always applies to velars

Competition between rules is resolved by the learners stochastically (they

don’t always go for the most reliable rule)

The adjectives seem derived from the PP’s: A bez- adjective always has a

corresponding PP but sometimes lacks a corresponding bez-less adjective

Since the preposition and the prefix are spelled differently, this may

make bez- especially hard to spell if the writer is uncertain whether

they are spelling a PP or an adjective at some processing stage,

compared, e.g., to the verbal prefix raz-, which does not have a

corresponding preposition it could be confused with

For native Russian speakers, velar palatalization is not very productive

before –i and –ik. How come the lexicon contains no exceptions to the

rule then?

This would in turn cause Russian writers to rely on retrieving

orthographic forms of adjectives from memory

I suggest the speakers rely on lexical retrieval to produce the forms that

seem to be obeying the rule (Butterworth 1983, Halle 1973, Zuraw 2000,

Albright & Hayes 2003). Plus, rule-violating forms may be perceived as

awkward (Zuraw 2000).

Google data

bez-

Mean 1%

Mean 35%

Mean 0%

raz-

Conclusions

Systems that look regular from a linguistic description

sometimes aren’t for the language users.

Human language learners do not maximize regularity to the

extent that linguists do.

Thus the learned grammars do not provide as much information

about the correct output as the grammar a linguist would

generate.

Future work: When are seemingly regular systems not? (e.g.,

Bybee 2008: morphologization reliance on retrieval)

References

Why look at orthography?

Orthography is designed to be and taught as a regular rule system

Much higher error rate for bezMuch stronger correlation of error rate with word frequency for bez-, esp. within lexemes:

e.g., countless .PL is more common than countless.SG and is spelled more accurately too

Bez-

Bez-

Raz-

In Russian, obstruents devoice before voiceless obstruents

Prediction confirmed

There may be competition even in what looks like a regular

system when the applicability of the rule is difficult to evaluate in

processing due to uncertainty regarding whether the input meets

the structural description

(Kapatsinski 2010b)

The rules:

-ik mostly attaches to

non-velars

This is likely due to competition between the spelling rules or

orthographic forms of bez-the-prefix and bez-the-preposition,

which are probably the same lexical entry

To cope with ambiguity in the output of the grammar, learners

rely on lexical retrieval whenever they can.

Case II: A regular spelling rule in Russian

-ik is the only

diminutive

suffix in front

of which velar

palatalization

often (35%) fails

While the same rule describes the spelling of bez- and raz-, the

spelling of bez- relies on lexical retrieval rather than rule

application but the spelling of raz- is largely rule-based

Albright, Adam, & Bruce Hayes . 2003. Rules vs. analogy

A computational/experimental study. Cognition, 90, 119–161.

in

English

past

tenses:

Butterworth, B. 1983. Lexical representation. In B. Butterworth (ed.), Language production ( Vol. II ):

Development, writing, and other language processes, 257–294. London: Academic Press.

Bybee, Joan. 2008. Formal universals as emergent phenomena: The origins of structure preservation.

In Jeff Good (ed.), Linguistic universals and language change, 108–121. Oxford: Oxford

University Press.

Halle, Morris. 1973. Prolegomena to a theory of word formation. Linguistic Inquiry, 4, 3-16.

For prefixes ending in /z/, the devoicing is supposed to be reflected in the

spelling

Kapatsinski, V. 2010a. Velar palatalization in Russian and artificial grammar: Constraints on models of

morphophonology. Laboratory Phonology, 1, 361-393.

Kapatsinski, V. 2010b. What is it I am writing? Lexical frequency effects in spelling Russian prefixes:

Uncertainty and competition in an apparently regular system. Corpus Linguistics and Linguistic

Theory, 6, 157-215.

Prefixes ending in other consonants and all stems, including prepositions, always

have a constant spelling independent of phonological context

Zuraw, Kie. 2000. Patterned exceptions in phonology. Los Angeles, CA: UCLA dissertation.

Conclusion: Reliance on inflected form retrieval to spell bez- but not raz-