Multilingual Writers - IWCA Summer Institute

advertisement

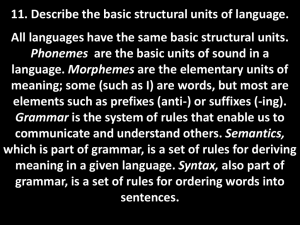

Carol Severino, carol-severino@uiowa.edu, University of Iowa ◦ Terminology ◦ Attitudes ◦ Principles ◦ Strategies International Resident Students Bilinguals In the US: AKA Visa Students, “Foreign Students” May be returning to their countries to live & work; motivation for learning English may be more instrumental than integrative (Garner & Lambert, 1972) Overseas: Students at English-medium national or USaffiliated universities might be in more of an English as-a-Foreign-Language (EFL) vs. English-as-a Second-Language (ESL) situation May be stronger in reading & writing, but weaker in speaking, listening, & knowledge of US culture & expressions AKA Immigrant ESL students; language minority students; English Language Learners (ELL); Generation 1.5 (Rumbaut & Ima, 1988) Learned English through informal spoken interactions; may therefore be fluent in informal spoken English Probably more aware (part) of US (youth) culture May speak (or are spoken to in) another language besides English at home. Have had some years of high school (& possibly middle & elementary school) in the US May have limited knowledge of English grammar May have limited L1 (home language) literacy May identify as fully bilingual, as native speakers of English (Matsuda & Matsuda, 2009), or as a member of the L1 culture. Resident Bilinguals Tend to Be Ear Learners of English Empathy Curiosity Knowing who our students are enables us to tutor them better. The “Just Ask” Approach Learning is reciprocal cultural exchange in the WC as “contact zone” (Pratt). Cultural relativity Linguistic relativity Rhetorical relativity In your first/home language, how do writers make arguments? What are the features of good communication & writing? How is this word or idea expressed in your first/home language? What do you miss most about China (Korea, the Sudan, India)? What impresses you most about the US (or your city or college)? What confuses you most about life in the US? Writing in English as a native or near native language is also hard for us tutors. Expressing on the page what is inside our heads precisely and effectively is a struggle for almost every writer. Writing is always a problem-solving process (Flower & Hayes, 1981), but L2 writing can present more problems to solve. Your own experiences studying or traveling in other countries, regions, or cultures. Your own experiences if you are also multilingual & multicultural. Your own experiences writing, speaking, reading, and listening in your own L2 & learning to write in new fields and genres. Curiosity & empathy go a long way but… We also need to know principles related to second language (L2) & literacy development It can take up to 7 years to acquire academic proficiency in an L2. (Collier, 1987). e.g., Students must know 9,000 word families for successful academic reading (Nation, 1996). Like L2 speaking, L2 writing, especially by international L2 writers, will probably always be “accented.” e.g. “I have done many researches on field of medicine.” Language proficiency is complex= the level of one’s ability to speak, read, write and listen in a language. includes fluency and accuracy. depends on knowledge & application of rules of grammar, syntax, vocabulary, pragmatics. Growth in proficiency is not always linear; learning can plateau, or even regress at times. the ability to function in the academic environment to comprehend lectures, & discussion comments of classmates. to collaborate with classmates. to comprehend readings (time). to comprehend and fulfill writing & speaking tasks. to know when & how to ask for help. Negative transfer of L1 features: Phonetic Grammatical Syntactic Lexical Discoursal/rhetorical [Handout] Transfer decreases as proficiency increases. System of tenses Agreement The pesky ‘s’ The word order of questions No, we must apply the principles to strategies to promote further learning of writing and language. Deductive vs. Inductive Organization: Thesis paragraph previews content & organization & features the main/controlling idea. Direct vs. indirect statement of ideas/arguments: Writer vs. reader responsibility Documentation of sources. Quoted material uses “ “ & is cited. Rhetoric is Situated : When in Rome…. Higher Order Concerns (HOCs): assignment fulfillment, argument, audience awareness, ideas, organization, support, clarity Lower Order Concerns (LOCs): grammar, mechanics, citation style. You can weave work on lower order concerns into work on higher order concerns. If you can, read to the end of the paper before you comment (Matsuda & Cox, 2009). Remember to praise what the writer did well or better. Ask student Tell-Me-More Questions about problems that obscure meaning (confusing passages) “Can you tell me more about what you say here?” “What do you mean by_____?” “Do you mean that________?” Indicate errors that are rule-based for the student to correct further=TREATABLE ERRORS. Help to correct those errors that don’t seem rule-based, e.g. faulty vocabulary/word choice=UNTREATABLE ERRORS, which often obscure meaning. Show curiosity; learning in the WC is reciprocal Empathize, Relativize Clarify academic & cultural expectations Give feedback without overwhelming Enjoy learning from multilingual students=an armchair travel & crosscultural opportunity Terminology: International Student from Korea Attitudes: Curiosity about and empathy with his experiences with replay culture and with his problem-solving processes Principles: Acquisition, Accent, Transfer, English syntax, vocabulary, grammar Strategies: Praise; Weaving the Local into the Global; prioritizing errors in meaning by asking tell me more questions, categorizing treatable vs. untreatable errors.