Recognition and Management of

Antibody-Mediated Rejection

Malcolm P. MacConmara, MB, BCh, BAO

Emory University School of Medicine, Atlanta, Georgia

A REPORT FROM THE 2013 AMERICAN TRANSPLANT CONGRESS

© 2013 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

1

Antibody-Mediated Rejection (AMR)

AMR is a major cause of acute and chronic allograft

dysfunction1,2

» Acute AMR occurs in at least 5%–7% of all kidney transplant

recipients and 25%–30% of presensitized crossmatchpositive patients.3

» Chronic AMR due to sensitization or de novo donor-reactive

antigen contributes to long-term allograft loss.2,4

AMR may result from reactivation of antibody

responses to preexisting antigens (type I) or de novo

to donor-specific antibodies (DSAs) encountered late

after transplant (type II), mostly as a result of

nonadherence to immunosuppressive therapy.5

© 2013 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

2

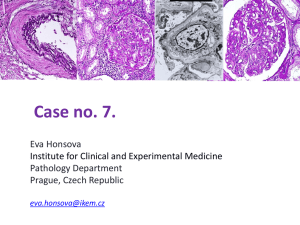

The Difficult Diagnosis of AMR

The current Banff classification of AMR relies upon

three cardinal features: (1) positive C4d staining,

(2) circulating DSA, and (3) tissue injury.

Histologic findings of injury vary.

Classification is based on clinical setting, underlying

pathophysiology, and temporal relationship to

transplantation (hyperacute, acute, and chronic).

Clinical manifestations range from immediate graft

loss to chronic subclinical rejection with gradual loss

of function.1–3

© 2013 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

3

Outcomes Associated with AMR

AMR has a worse outcome than acute cellular

rejection (ACR), likely because of diagnostic

difficulty and less-effective therapeutic options.

Among renal transplant recipients with AMR,

15%–20% lose their grafts within 1 year.6

More than 40% of patients with AMR eventually

develop transplant glomerulopathy, whether or not

initial treatment can reverse acute renal functional

impairment.

AMR-related glomerulopathy is associated with

< 50% 5-year graft survival from the time of

identification.6

© 2013 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

4

Targets and Therapies

Development of antibody-mediated rejection1

MMF = mycophenolate mofetil; TH cell = T-helper cell; IVIg = immunoglobulin-

© 2013 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

5

Targets and Therapies

Therapeutic options for AMR1,2,7 include:

Inhibition or depletion of B-cell function with

rituximab or corticosteroids

Interference with antibody function using

plasmapheresis, immunoadsorption, and/or

intravenous immunoglobulin (IVIg)

Interruption of plasma-cell function with bortezomib

Prevention of complement cascade using eculizumab

© 2013 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

6

The Population and the Risks

Over 96,000 patients currently are registered on the

waiting list for kidney transplantation.

» Almost 16% are prior organ-transplant recipients.

» Approximately 30% are sensitized to human leukocyte

antigen (HLA).8

» Highly sensitized patients with > 80% panel-reactive

antibody (PRA) wait three times longer to undergo

transplant surgery than do unsensitized renal transplant

recipients and have an average wait time of almost 10

years.9

Desensitized patients continue to have an increased

incidence of type I AMR and graft loss.10

© 2013 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

7

Pathophysiology in Sensitized Patients

Type I AMR in desensitized patients apparently

involves residual plasma cells and long-lived

allospecific memory B cells.11

Approximately one fourth of desensitized recipients

experience early AMR, usually within the first week

after transplant.12

Two thirds of these patients respond to

plasmapheresis.

The remainder may experience severe oliguric,

plasmapheresis-resistant rejection, which often is

accompanied by graft loss.

© 2013 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

8

Pathophysiology in Sensitized Patients

The principal effector mechanism of antibody-mediated

injury involves activation of the classic complement

pathway by the antigen-antibody complex deposition.13

Ig = immunoglobulin; HLA = human leukocyte antigen; DAF = decay-accelerating factor; Y-CVF = Yunnan-cobra venom factor

© 2013 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

9

Treatment of AMR: Plasmapheresis

Montgomery et al14 used plasmapheresis with IVIg to

reduce DSA strength before transplantation.

Induction with antithymoglobulin and steroids with

maintenance immunosuppression (tacrolimus and

mycophenolate mofetil) prevented AMR in most

desensitized patients.

» One third received anti-CD20 immediately before

transplant.

» Desensitization improved patient survival to 90% and 80%

at 1 and 5 years, respectively, as compared with 93% and

65% among those waiting for compatible donors.

© 2013 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

10

Treatment of AMR: Plasmapheresis

Montgomery and colleagues12 reported a 22%

incidence of early AMR that mostly responds to

further treatment with plasmapheresis and IVIg.

Approximately 50% of treated patients lose grafts

within 2 years.

Addition of complement inhibitor to splenectomy

has increased the rescue rate and significantly

reduced the development of tubular

glomerulopathy.12

© 2013 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

11

Phenotypes and Outcomes

Plasmapheresis better eliminates type I antibody

generated to major histocompatibility complex

(MHC) class I than it eradicates MHC class II

antigen.

Other phenotypes associated with poor outcome

include C4d-positive staining with glomerulitis,

peritubular capillaritis, and microcirculatory

inflammation.

» These differ from results seen in the setting of type II AMR.

» Further studies must incorporate immunologic and

histopathologic parameters into treatment algorithms that

balance risk with degree of therapeutic aggression.

© 2013 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

12

Complement Inhibition

Stegall and others15 compared 26 patients

desensitized to levels of low-to-moderate antibody

strength given eculizumab post transplant with 51

matched controls.

Within the first 3 months after transplant, AMR

occurred in 7.7% of patients given eculizumab and

41% of matched controls.

Protocol-required biopsies examined up to 1 year

after treatment showed no evidence of transplant

glomerulopathy.

© 2013 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

13

Risk of Rejection and DSA Titer and Type

DSAs are most commonly directed against HLA class

I (on all nucleated cells) or class II (on antigenpresenting cells and endothelial cells).

» DSAs may develop against non-HLA antigens, including

MHC class I–related chain A and B (MICA, MICB),

molecules of the renin-angiotensin pathway, and plateletspecific antigens2

DSA level, expressed as mean fluorescent intensity

(MFI), is proportional to the risk of rejection.

» Complement inhibition did not alter the DSA level but

reduced AMR in patients with a high DSA concentration

(control group, 100%; study group, 15%).15

© 2013 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

14

Eculizumab-Resistant AMR

Treatment of late AMR with findings suggesting

acute cellular rejection and AMR may involve

thymoglobulin, plasma exchange, and eculizumab.

Chronic AMR accompanied by negative C4d staining

may be a form of complement-independent rejection

and eculizumab-resistant rejection.

The best treatment of chronic AMR appears to be a

combination of therapeutic approaches, such as

combining bortezomib therapy with plasma

exchange and IVIg.16

© 2013 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

15

C4d-Negative AMR

Traditionally, detection of C4d has been required for

AMR diagnosis. However:

» Many C4d-negative cases have clinical and histologic

findings similar to those of rejection and exhibit DSAs.

» A substantial fraction of cases of chronic graft failure

previously labeled as calcineurin-inhibitor nephrotoxicity

may result from C4d-negative AMR.4

Sis et al17 examined 329 biopsy samples from

patients with graft dysfunction.

» Peritubular capillaritis and glomerulitis often were not

associated with DSA (27%) during year 1 post transplant.

© 2013 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

16

Molecular Scoring

Predictive molecular scoring systems based upon

levels of gene expression increasingly are being used

to augment standard diagnostic histopathology,

which fails to improve risk stratification.

The Banff Working Group5 is addressing a number of

approaches related to deficiencies, including:

» IgG subtyping

» MFI levels of DSA

» C1q-fixing DSA

© 2013 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

17

Molecular Scoring

Sellarés et al18 used Affymetrix microarray

technology to identify type II AMR in study biopsies

obtained 1 year post-transplant.

For many patients, biopsy results were related to

medication nonadherence.4

Survival was linked to timing of the biopsy and the

disease process identified.

The risk of graft loss was greatest during the initial

3 years following indication biopsy.

© 2013 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

18

Genetic Predisposition

A cohort of 30 human genes strongly associated with

AMR have been identified and validated.18

The genes include cadherin 13 (CDH13), chemokine

(C-X-C motif) ligands 10 and 11 (CXCL10 and

CXCL11), and fibroblast growth factor binding

protein 2 (FGFBP2), all of which are associated with

endothelial injury and cellular trafficking.

This molecular fingerprint, applied to all samples,

may be used to discriminate between AMR and other

causes of acute deterioration in graft function.18

© 2013 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

19

Subclinical AMR

Subclinical AMR is defined as graft changes that meet

established pathologic and serologic criteria for AMR

without graft dysfunction or concurrent ACR:

Serum creatinine level remains unchanged.

DSAs have low MFI values in the absence of

proteinuria.

Patients repeatedly undergo biopsy without

exhibiting clear evidence of rejection before

developing clinical and pathologic changes.

Quiescent disease may erupt later as a result of an

immunologic trigger.

© 2013 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

20

Subclinical AMR

Risk of graft loss is 77% higher among patients with

DSAs.

Some DSAs are more likely than others to result in

graft rejection.

Non-HLA and non-complement fixing antibody may

be responsible for subclinical AMR.

© 2013 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

21

Accommodation vs Subclinical Rejection

Accommodation is defined as the presence of

inhibitory mechanisms to the distal complement

cascade downstream of C4d cleavage.

Accommodation is often is seen in protocol-required

biopsies after ABO-incompatible transplantation.

Aside from ABO incompatibility, desensitized

patients with C4d-positive staining typically

experience tissue injury.

There is no way to differentiate C4d-positive biopsies

that represent accommodation from subclinical

AMR-mediated rejection.19

© 2013 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

22

C4d-Negative AMR

Approximately 10% of biopsies with features of acute

AMR are C4d negative.

Rejection may occur through complementindependent mechanisms.

Sis et al20 used microarray analysis to demonstrate

increased endothelial cell gene expression in biopsies

having histopathologic findings of AMR and DSA but

negative C4d staining.

This approach may represent a novel method of

AMR detection.

© 2013 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

23

Management of Subclinical AMR

Not all DSAs appear to pose the same risk.

Molecular phenotyping and electron microscopy may

help in detecting and managing subclinical AMR.

Gloor et al21 reported that treating desensitized renal

transplant recipients with subclinical AMR using

corticosteroids, plasmapheresis, and IVIg resolved

the histologic abnormalities; however, the long-term

clinical outcome of this strategy is unclear.

© 2013 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

24

Summary

Better understanding of acute AMR is the foundation

for successful treatment of desensitized patients by

blocking multiple points of the pathway.

Chronic AMR is a major cause of late graft loss and

remains less understood than acute AMR.

New gene-based molecular approaches to the

diagnosis of AMR offer hope of more timely and

effective treatment.

© 2013 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

25

References

1.

Levine MH, Abt PL. Treatment options and strategies for antibody mediated rejection after renal

transplantation. Semin Immunol. 2012;24:136–142.

2.

Puttarajappa C, Shapiro R, Tan HP. Antibody-mediated rejection in kidney transplantation: a review. J

Transplant. 2012;2012:193724.

3.

Lucas JG, Co JP, Nwaogwugwu UT, Dosani I, Sureshkumar KK. Antibody-mediated rejection in kidney

transplantation: an update. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2011;12:579–592.

4.

Sellarés J, de Freitas DG, Mengel M, et al. Understanding the causes of kidney transplant failure: the

dominant role of antibody-mediated rejection and nonadherence. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:388–399.

5.

Mengel M, Sis B, Haas M, et al. Banff 2011 meeting report: new concepts in antibody-mediated rejection.

Am J Transplant. 2012;12:563–570.

6.

Gloor JM, Cosio FG, Rea DJ, et al. Histologic findings one year after positive crossmatch or ABO blood

group incompatible living donor kidney transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2006;6:1841–1847.

7.

Fehr T, Gaspert A. Antibody-mediated kidney allograft rejection: therapeutic options and their

experimental rationale. Transplant Int. 2012;25:623–632.

8.

Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN) Web site. http://optn.transplant.hrsa.gov.

Accessed July 5, 2013.

9.

Jordan SC, Reinsmoen N, Peng A, et al. Advances in diagnosing and managing antibody-mediated

rejection. Pediatr Nephrol. 2010;25:2035–2045.

10. Paramesh AS, Zhang R, Baber J, et al. The effect of HLA mismatch on highly sensitized renal allograft

recipients. Clin Transplant. 2010;24:E247–E252.

11. Stegall MD, Dean PG, Gloor J. Mechanisms of alloantibody production in sensitized renal allograft

recipients. Am J Transplant. 2009;9:998–1005.

© 2013 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

26

References

12. Montgomery RA, Warren DS, Segev DL, Zachary AA. HLA incompatible renal transplantation. Current

Opin Organ Transplant. 2012;17:386–392.

13. Stegall MD, Chedid MF, Cornell LD. The role of complement in antibody-mediated rejection in kidney

transplantation. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2012;8:670–678.

14. Montgomery RA, Lonze BE, King KE, et al. Desensitization in HLA-incompatible kidney recipients and

survival. N Engl J Med. 2011;365:318–326.

15. Stegall MD, Diwan T, Raghavaiah S, et al. Terminal complement inhibition decreases antibody-mediated

rejection in sensitized renal transplant recipients. Am J Transplant. 2011;11:2405–2413.

16. Trivedi HL, Terasaki PI, Feroz A, et al. Abrogation of anti-HLA antibodies via proteasome inhibition.

Transplantation. 2009;87:1555–1561.

17. Sis B, Jhangri GS, Riopel J, et al. A new diagnostic algorithm for antibody-mediated microcirculation

inflammation in kidney transplants. Am J Transplant. 2012;12:1168–1179.

18. Sellarés J, Reeve J, Loupy A, et al. Molecular diagnosis of antibody-mediated rejection in human kidney

transplants. Am J Transplant. 2013;13:971–983.

19. Park WD, Grande JP, Ninova D, et al. Accommodation in ABO-incompatible kidney allografts, a novel

mechanism of self-protection against antibody-mediated injury. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:952–960.

20. Sis B, Jhangri GS, Bunnag S, Allanach K, Kaplan B, Halloran PF. Endothelial gene expression in kidney

transplants with alloantibody indicates antibody-mediated damage despite lack of C4d staining. Am J

Transplant. 2009;9:2312–2323.

21. Gloor JM, DeGoey SR, Pineda AA, et al. Overcoming a positive crossmatch in living-donor kidney

transplantation. Am J Transplant. 2003;3:1017–1023.

© 2013 Direct One Communications, Inc. All rights reserved.

27