Nevada del Ruiz

advertisement

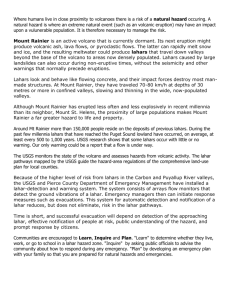

Nevada del Ruiz 1985 Background Info Location Nevada del Ruiz is located on the border of the departments of Caldas in Colombia about 129 km west of the capital city Bogota. It is the northernmost of several Colombian stratovolcanoes in the Andes Volcanic Chain. The Andean volcanic belt is generated by the eastward subduction of the Nazca oceanic plate beneath the South American continental plate. Typically, such stratovolcanoes generate explosive Plinian eruptions with associated pyroclastic flows that can melt snow and glaciers near the summit, thus producing devastating lahars. The Volcano Itself is a stratovolcano composed of many layers of lava alternating with a hardened volcanic ash and other pyroclastic rocks. It has been active for roughly two million years with three major eruption periods. The current volcanic cone formed during the present eruption period which began 150 thousand years ago. With a summit elevation of 5,389m it is the highest of the Colombian volcanoes. November 1985 Eruption Early morning After nearly a year of minor earthquakes and steam explosions from Nevado del Ruiz, the volcano exploded violently on November 13, 1985. The initial blast began at 3:06 p.m., and two hours later pumice fragments and ash were showering down on Armero. However, the citizens of Amero remained calm. They were placated by reassuring messages from the mayor over radio, and from a local priest over the church public address system. Nevertheless, the Red Cross ordered an evacuation of the town at 7:00 p.m. However, shortly after the evacuation order the ash stopped falling and the evacuation was called off. At 9:08pm just as calm was being restored, molten rock began to erupt from the summit crater for the first time. The violent ejection of this molten rock generated hot pyroclastic flows and air fall tephra that began to melt the summit ice cap. Unfortunately, a storm obscured the summit area so that most citizens were unaware of the pyroclastic eruption. Melted water quickly mixed with the erupting pyroclastic fragments to generate a series of hot lahars. One lahar flowed down the River Cauca, submerging the village Chinchina and killing 1,927 people. Other lahars followed the paths of the 1595 and 1845 mudflows. Traveling at 50 kilometers per hour, the largest of these burst through an upstream damn on the River Lagunillas and reached Armero two hours after the eruption began. Most of the town was swept away or buried in only a few short minutes, killing three quarters of the townspeople. Devastating Impacts When rescuers arrived They were greeted by tangled masses of trees, cars and mutilated bodies scattered throughout an ocean of grey mud. Injured survivors lay moaning in agony while workers tried frantically to save them. Roughly 23,000 people and 15,000 animals were killed. Another 4500 people were injured and 8000 made homeless. The estimated cost was $1 Billion or 1/5th of Colombia's Gross National Product. Impact of the Lahars The lahars, formed of water, ice, pumice and other rocks, mixed with clay as they travelled down the volcano's flanks. They ran down the volcano's sides at an average speed of 60 km per hour destroying everything in its path. After descending thousands of meters down the side of the volcano, the lahars were directed into all of the six river valleys leading from the volcano. While in the river valleys, the lahars grew to almost 4 times their original volume. In the Gualí River, a lahar reached a maximum width of 50 meters. One of the lahars virtually erased the small town of Armero in Tolima, which lay in the Lagunilla River valley. As mentioned before only one quarter of its inhabitants survived. The second lahar, which descended through the valley of Chinchiná River, killed about 1,800 people and destroyed about 400 homes in the town of Chinchiná. The Armero tragedy, as the event came to be known, was the second-deadliest volcanic disaster in the 20th century, being surpassed only by the 1902 eruption of Mount Pelée, and is the fourth-deadliest volcanic eruption in recorded history. Could this be averted ? Nevado del Ruiz had served up a steady menu of minor earthquakes and steam eruptions for 51 weeks prior to the November 13 eruption. The on-going activity was just enough to keep people nervous, but not enough to convince authorities that the volcano provided a real threat. Since Colombia had no equipment to monitor the volcano, or geologists skilled in using such equipment, expertise could only come from other countries. A scientific commission and some journalists visited the crater in late February and soon after a report of the volcanic activity first appeared in the newspaper La Patria in early March. By July, seismographs were obtained from several countries to monitor earthquakes which would help in plotting the movement of rising magma beneath the volcano. Money was obtained from the Unified Nations to help map the areas that were thought to be at the greatest risk. The resulting report and volcanic hazards map were finished on October 7, but only ten copies were distributed. Based on the report, the National Bureau of Geology and Mines (INGEOMINAS) declared that a moderate eruption would produce " . . . a 100 percent probability of mudflows . . . with great danger for Armero . . . Ambalema, and the lower part of the River Chinchina." However, some government officials dismissed the report as "too alarming" and authorities did not want to evacuate people until they were assured of the necessity. Continuous earth tremors began beneath the volcano on November 10. This prompted a group of scientists to visit the crater again on November 12. However, they saw nothing to suggest eminent danger and they did not recommend an evacuation. The 23,000 people that would die the following day would Improvement strategies As the Armero tragedy was exacerbated by the lack of early warnings, unwise land use and the unpreparedness of nearby communities, the government of Colombia created a special program (Oficina Nacional para la Atencion de Desastres, 1987) to prevent such incidents in the future. All Colombian cities were directed to promote prevention planning in order to mitigate the consequences of natural disasters and evacuations.