HOLMES CHAPTER SIX THE KILLING OF INNOCENT PERSONS

advertisement

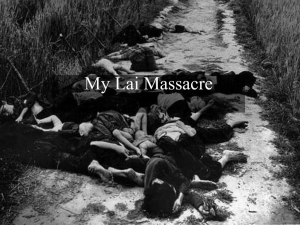

HOLMES CHAPTER SIX THE KILLING OF INNOCENT PERSONS IN WARTIME JUS IN BELLO raise moral problems for all armed conflict, even those with ‘just cause.’ The end cannot only be just; the means to the end must be just. “If the means necessary to waging war cannot be justified, then war cannot be justified and no war can be just.” Most just war theorists impose limitations on conduct in war. Two restrictions (1) Whom you can kill and (2) How you can kill them. The most serious prohibition is the killing of innocent persons. The strongest moral presumption is: Do not harm innocent people. Questions (1) Who is responsible? (2) Who is innocent? What makes a party innocent or guilty in the conflict? The burden of proof is on the person who would harm the innocent. It is presumptively wrong to kill the innocent. War necessarily kills innocent people in substantial numbers. If war inevitably involves such killing, what does this mean for the moral rightness of war? What is innocence? A standard view: Combatants are noninnocent/guilty; non-combatants are defenseless and so innocent. Holmes: Moral guilt does not coincide with legal guilty. The moral wrong of war depends on the initiation of war or the conduct of war. So a person could be guilty of other things, but innocent witih respect to thewar. Innocence/Guilt “If one person robs a bank, another keeps the car running, a third provides the gun, and a fourth knows of the robbery but does not stop it, the first is clearly guilty and the others culpable to various degrees… “(p. 185) But with war, the morally guilty are the most detached from the actual killing. The soldiers usually have no say and are detached from the enterprise. They may also be young, and deceived by the government. Are they responsible? Another problem Both sides may think they are in the right. But only one side is in the right. The killing of anyone who has done no wrong in the war is the wrongful killing of an innocent person. All the killing by the unjust parties is unjust killing of innocent people—whether they are soldiers, politicians or civilians. So combatant/non-combatant is not a good distinction between innocent/noninnnocent. Six categories of members ofa nation (1) Initiators of wrongdoing/govt leaders (2) Agents of wrongdoing (military commanders and combat soldiers) (3) Contributors to the war effort (munitions workers…taxpayers…) (4) Those who approve of the war without contributing in any significant way (5) Noncontributors/non-supporters (young children, political resisters the mentally ill, etc.) (6) Those who could contribute in the future (children) (p. 187) Moral innocence Obviously children are morally innocent. But Holmes says even those contributing to the war effort (growing, selling food, etc?) can be morally innocent of the war. Modern war will inevitably kill innocent people. War inevitably kills innocent people In mid-20th century the civilian casualty ratio was estimated by the Red Cross to be 10:1. 10 civilians for every soldier. It is very difficult to determine rate of civilian death because it is always contested. Iraq Body Count estimates 109,000 but counts all who are killed by violence. Justifications for killing civilians Kaiser in WWI: “If I admit considerations of humanity [the war] will be prolonged for years…”] (p. 188) US after Pearl Harbor decided to “execute unrestricted air and submarine warfare against Japan…including merchant ships…” Killing innocent civilians is presumptively wrong. Modern war always kills innocent civilians so it is presumptively wrong. The Accidental Killing of Innocents Collateral damage: Attempts are usually made by the double effect principle. One action can have many foreseeable effects. But if the intent is directed to a permissible effect the person performing the action is not guilty of all effects. The Double Effect So if the intention of a military attack is to attack a military target and reasonable attempts are made to protect civilians then there is no guilt from the attack even if a number of innocent civilians die. Act must be good or at least indifferent, bad effect must not be a means to the good and the good effect must be proportionate to the bad…If one intends the good, the action is not then wrong. Is this a good principle? Anscombe’s argument “The distinction between…intended and foreseen…is essential to Christian ethics…If I am answerable for the foreseen consequences or the refusal then the prohibitions will break down. If someone innocent will die unless I do a wicked thing then I am his murderer in refusing; so al that is left to me is to weigh up evils…[Theologian steps in and says] No you are no murderer if the mans death was neither your aim or your chosen means…” Ambiguity The claim that it is wrong to kill innocents contains an ambiguity. Does it mean it is in fact right in the world as it is or in any conceivable world? Is it wrong in all conceivable circumstances? That would be ridiculous. What it means is that it is wrong to intentionally kill innocents. But this doesn’t stop you from killing innocents. Paul Ramsey: “The deaths of noncombatants are only to be indirectly done and should be unintended...” even if there is certain knowledge they will be killed. Holmes’ objection 1 to the Double-Effect The DDE is inconsistent. How can you have two identical acts but one is good and one is bad when there is nothing different about the acts themselves just the intentions? Pilot A drops a bomb that will kill everyone in the area but only intends to kill the military people. Pilot B drops a bomb that will kill everyone in the area because he intends to do that. They are the same act but one is OK and the other is not. H says this is inconsistent. Holmes Objection 2 to the Double Effect The principle seems to allow way too much based on actors psychological state. “…we can ‘direct’ or ‘aim’ intentions as we please…” So “from a practical standpoint” [the principle is vacuous [empty].” (p. 199) Another defense of killing innocents As long as war does not kill innocent civilians in large numbers it is not wrong. Accidental auto deaths do not make highway construction wrong, for example. Is this a good argument? Holmes’ Reply There are some good inferences where a property of a part can be ascribed to a whole—if the car’s brakes are untrustworthy the car is untrustworthy. Is this a good inference in the case of war? Is evaluation of action the right method? Postivistic realism. War is a whole set of acts and can’t be evaluated by discrete acts. Tolstoy: Wars don’t even have causes in the ordinary sense. Rapoport: Wars are cataclysmic happenings like natural disasters? Is it a mistake to apply personal morality to war? Holmes’ Reply Consider Nuremberg: Individuals were held responsible for the war. Actions are the heart of war. Individuals commit the action. The killing is foreseeable. “…if one respects the prohibition against killing innocent persons, he will not kill innocent persons; and if not killing innocents means not waging war, he will not wage war.” (193) But don’t we have to go to war? What happens in this situation: If we don’t kill some innocent people, many more innocent people will die? Holmes: One never has to kill innocent people. However, sometimes the war is with a very brutal opponent. What then? The argument assumes (1) Killing is the same as letting people die (at others’ hands) and (2) If you don’t fight innocents will be killed. Aren’t pacifists just concerned with their own moral purity? Who is responsible? Holmes: Moral responsibility is not the same as causal responsibility. To be morally responsible though, you have to play some role in the cause. Kent State shootings: The guardsmen shot the students. But were they responsible for protesting and so creating the situation? Holmes: There is no morally neutral account of the facts. There are facts but the relevance of the fact is always couched within moral judgments. So you have to determine what is morally the case first? Determining Responsibility is difficult The issue is: If you are facing a violent and brutal enemy and they will kill people are you responsible for not killing some people when that might prevent them from killing other people? Unmediated consequences: E.g., you die because you are shot by a firing squad Mediated consequences: Those who pass sentence on to commanding officer, members of the firing squad who respond, etc. All count—but we have trouble with the unmediatedc consequences. Thoreau: Just do what’s right Making all mediated consequences count is a problem because then we are responsible for everything that everyone else does. Those who think that ‘if they should resist [unjust laws] the remedy would be the worse than the evil…”it is the fault of the government itself that the remedy IS worse than the evil. It makes it worse…” Example of dilemma: Is it the PLOs fault if the Israelis bomb areas with civilians because that is where the PLO hides? Contextual determination of responsibility Holmes: We can’t determine this in advance. It is contextual. E.g., if bigots hate interracial marriage, this doesn’t make interracial marriage wrong. But if someone gives a hate filled speech and it causes a riot, they could be partially responsible. Killing of innocents “One can’t assume that the deaths of innocents at the hands of aggressors are the consequence of the refusal of others to kill innocents…” (208) Is allowing a person to die the same as killing the person? What are the morally relevant differences? Killing and letting die We are always ‘letting’ people die? We could change our lives to save the lives of the starving at any time. Murphy: We have “a greater obligation to refrain from killing innocent person than we do to save them…” Not everyone has a right to have their death prevented at all costs. But every innocent person has a right not to be killed. Holmes: If I kill innocent persons to save other innocent person I am using THOSE innocent persons as a means to an end. What about the noninnocent? It’s not necessarily OK to kill the noninnocent either. What about utilitarian arguments? Are they the only good reasons left for letting the innocent live?