INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION * UCL, JANUARY 2014

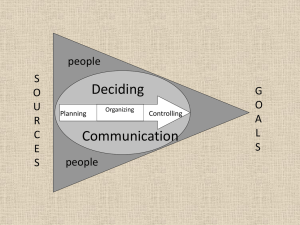

advertisement

UNIVERSITY OF ECONOMICS IN BRATISLAVA, SLOVAK REPUBLIC INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL – JANUARY, 2014 lecturer Milan Oresky INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 8. Asian Versus America Iceberg. Interfaces in multiple culture model within negotiation INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 9. Interfaces in multiple culture model within negotiation INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 Cross-Culture Comparisons Hight-Context (V.S) Low-Context Cultures Deal-Orientated (V.S) Relationship – Orientated Cultures INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 High- and Low-Context Cultures (Hall) Low-context cultures rely on explicit explanations, with emphasis on spoken words. Such cultures emphasize clear, efficient, logical delivery of verbal messages. Communication is direct. Agreements are concluded with specific, legal contracts High-context cultures emphasize nonverbal or indirect language. Communication aims to promote smooth, harmonious relationships. Such cultures prefer a polite, “face-saving” style that emphasizes a mutual sense of care and respect for others. Care is taken not to embarrass or offend others. INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 High- & Low-Context Cultures INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 Deal vs. Relationship Orientation In deal-oriented cultures, managers focus on the task at hand, are impersonal, typically use contracts, and want to just “get down to business.” Examples are Australia, Northern Europe, and North America In relationship-oriented cultures, managers value affiliations with people, rapport, and getting to know the other party in business interactions. Relationships are more important than individual deals, and trust is valued highly in business agreements. Examples are China, Japan, and Latin American countries. It took nine years for Volkswagen to negotiate a car factory in China INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 Hofstede’s Typology of National Culture Power distance describes how a society deals with inequalities in power that exist among people High power distance societies exhibit big gaps between the weak & powerful. In firms, top management tends to be autocratic, giving little autonomy to lower-level employees. Examples: Guatemala, Malaysia, Philippines, and several Middle Eastern countries Low-power distance societies have small gaps between the weak and the powerful. Firms tend toward flat organizational structures, with relatively equal relations between managers & workers. For example, Scandinavian countries have instituted various systems to ensure socioeconomic equality INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 Typology of National Culture Individualism vs. collectivism refers to whether a culture focuses primarily on individuals or whether it values group membership In individualistic societies, there is great emphasis on selfinterest; competition for resources is the norm; and individuals who compete best are rewarded. Examples: Australia, Britain, Canada, and the U.S In collectivist societies, ties among individuals are important; business is conducted in a group context; it’s important to keep conflict at a minimum; conformity and compromise help maintain harmony. Examples: China, Panama, Japan, and South Korea INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 Typology of National Culture Uncertainty avoidance refers to the extent to which people can tolerate risk and uncertainty in their lives High uncertainty avoidance societies create institutions to minimize risk and ensure security. Firms emphasize stable careers and regulate worker actions. Decisions are made slowly. Examples are Belgium, France, and Japan In low uncertainty avoidance societies, managers are relatively entrepreneurial and comfortable with risk. Firms make decisions quickly. People are comfortable changing jobs. Examples are Ireland, Jamaica, and the U.S INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 Typology of National Culture Masculinity versus femininity refers to a society’s orientation based on traditional male and female values. Masculine cultures value competitiveness, ambition, assertiveness, & the accumulation of wealth. Both men and women are assertive, focused on career and earning money. Examples are Australia and Japan Feminine cultures emphasize nurturing roles, interdependence among people, and caring for less fortunate people—for both men and women. Examples are Scandinavian countries, where welfare systems are highly developed and education is subsidized INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 Typology of National Culture Long-term versus short-term orientation describes the degree to which people and organizations defer gratification to achieve longterm success Long-term orientation emphasizes a longer view of planning & living (years/decades vs. months). Examples are traditional Asian cultures (China, Japan, Singapore) where teachings of Confucius about discipline, hard work, & education are key values Short-term orientation is typical in the U.S. and most other Western countries INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 Subjective Dimensions of Culture Values represent a person’s judgments about what is good or bad, acceptable or unacceptable, important or unimportant, and normal or abnormal Attitudes and preferences are developed based on values. They are similar to opinions, except that attitudes are often unconsciously held and may not have a rational basis Examples Values common to Japan, North America, and Northern Europe include hard work, punctuality, and wealth acquisition. INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 Manners and Customs Ways of behaving and conducting oneself in public and business situations Manners and customs are present in eating habits, mealtimes, work hours & holidays, drinking & toasting, appropriate behavior at social gatherings (kissing, handshaking, bowing), gift-giving (complex), the role of women, & more. It is a mistake to minimize the importance of knowing customs of another culture, not simply b/c it could offend, but also because it can signal that you are not prepared & thus could be taken advantage of... INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 Perceptions of Time Time dictates expectations about planning, scheduling, profit streams, and what constitutes tardiness in arriving for work and meetings Monochronic: A rigid orientation to time in which the individual is focused on schedules, punctuality, and time as a resource. Time is linear, and “time is money.” For example, people in the U.S. are hurried and impatient Polychronic: A flexible, non-linear orientation to time in which the individual takes a long-term perspective. Time is elastic, and long delays are tolerated before taking action. Punctuality is relatively unimportant. Relationships are valued. Examples are Africa, Latin America, and Asia INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 Religion A system of common beliefs or attitudes regarding a being or system of thought that people consider sacred, divine, or the highest truth - & the associated moral values, traditions, & rituals Influences behavior. Example: The “ Protestant work ethic ” emphasizes hard work, individual achievement, and a sense that people can control their environment—the underpinnings for the development of capitalism. Islam ’ s holy book, the Qur ’ an, prohibits drinking alcohol, gambling, usury, and “ immodest ” exposure. The prohibitions affect firms dealing in various goods & services culture, and therefore business and consumer INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 Language as a Key Dimension of Culture Language is the “mirror” or expression of culture; it is essential for communications and provides insights into culture Linguistic proficiency is a great asset in international business Language has both verbal and nonverbal components (i.e., facial expressions and gestures) There are nearly 7,000 active languages, including over 2,000 in both Africa and Asia INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 Managerial Guidelines for Cross-Cultural Success Acquire factual and interpretive knowledge about the other culture; try to speak its language Avoid cultural bias Develop cross-cultural skills, such as perceptiveness, interpersonal skills, and adaptability INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 Personality Traits for Cross-Cultural Proficiency Tolerance for ambiguity: Ability to tolerate uncertainty and lack of clarity in the thinking and actions of others Perceptiveness: Ability to closely observe and comprehend subtle information in the speech and behavior of others Valuing personal relationships: Ability to appreciate personal relationships, often more important than achieving one-time goals or “winning” arguments Flexibility and adaptability: Ability to be creative in devising innovative solutions, be open-minded about outcomes, and show “grace under pressure” INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 9. Ethics in international Business Moral principles and values that affect behavior of individuals, companies, and governments Ethics tell us what’s right or wrong Sometimes easier to understand than it is to actually put it in practice And, sometimes easier to know what’s wrong than what’s right to do INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 Inappropriate Conduct Corruption is the abuse of power to achieve illegitimate personal gain Bribery is common and can take the form of grease payments, small inducements intended to expedite decisions and transactions or gain favors INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 The Value of Ethical Behavior Ethical behavior is simply the right thing to do. It is often prescribed within laws and regulations Often required by laws and regulations Ethical behavior is demanded by customers, governments, and the news media. Unethical firms risk attracting unwanted attention Ethical behavior is good business, leading to enhanced corporate image and selling prospects. Firms with strong reputations have an advantage when hiring and motivating employees, partnering, and dealing with foreign governments INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 Variation in Ethical Standards Ethical standards vary from country to country Relativism is the belief that ethical truths are not absolute but, rather, differ from group to group. This perspective is summarized by the phrase, “When in Rome, do as the Romans do.” Normativism is the belief that ethical behavioral standards are universal and that firms and individuals should seek to uphold them consistently around the world INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 An Ethical Dilemma Imagine you are a manager visiting a factory owned by an affiliate in Colombia. During this you discover the use of child labor in the plant You are told that without the income they receive from their children’s work, their families might go hungry. If the children are dismissed from the plant, they will likely turn to other income sources, including prostitution and street crime What should you do? Raise the issue of the immorality of child labor or look the other way? INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 Corporate Social Responsibility Corporate social responsibility: Manner of operating a business that meets or exceeds the ethical, legal, commercial, and public expectations of customers, shareholders, employees, and communities A strong CSR can: Help recruit and retain good employees Help differentiate the firm and enhance its brands Help cut costs, such as minimizing packaging, recycling, economizing on energy usage, and reducing waste in operations Help the firm avoid increased taxation, regulation, or other legal actions by local government authorities INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 Corporate Governance Corporate Governance: The system of procedures and processes by which corporations are managed, directed, and controlled It provides the means through which firms undertake ethical behaviors, CSR, and sustainability Implementing appropriate conduct is challenging for MNEs, especially when operating in many countries A complicating factor is the use of third-party suppliers and contractors, some of which may behave badly Most firms incorporate ethics and CSR into their mission, planning, strategy, and everyday operations INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 Ethical Standards for Corporate Governance Ethical Standards for Corporate Governance Utilitarian Approach This approach argues the best ethical action is the one that provides the most good or the least harm. It produces the greatest balance of good over harm to customers, employees, shareholders, the community, and the natural environment. Rights Approach This approach instructs the decision maker to choose the action that best protects and respects the moral rights of everyone involved. It is based on the belief that, regardless of how you deal with an ethical dilemma, human dignity must be preserved. Fairness Approach This approach advises that everyone should be treated equally and fairly. Workers should be paid a fair wage that provides a decent standard of living, and colleagues and customers should be treated as we would like to be treated. Common Good Approach This approach suggests that actions should be based on the welfare of the entire community or nation. It asks which action contributes most to the quality of life of all affected people. Respect and compassion for all, especially the vulnerable, should be the basis for decision making. Virtue Approach This approach advocates that ethical actions should be consistent with certain ideal virtues that provide for the full development of our humanity. The most important virtues are truth, courage, compassion, generosity, tolerance, love, integrity, and prudence. INTERNATIONAL NEGOTIATION – UCL, JANUARY 2014 Questions?