Capital Formation, Investment Choice, Information Technology

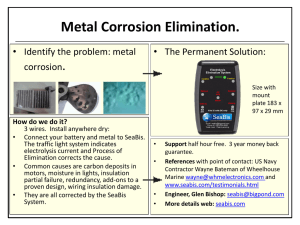

advertisement

Chapter 11 Capital Formation, Investment Choice, Information Technology and Technical Progress CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 1 Capital Formation, Investment Choice, Information Technology & Technical Progress Capital Formation & Technical Progress as Sources of Growth. Components of the Residual. Learning by Doing. Growth as a Process of Increase in Inputs. CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 2 Capital & Technology (Cont) The Cost of Technical Knowledge. Research, Invention, Development, & Innovation. Computers, Electronics, & Information Technology. Investment Criteria. Differences between Social & Private Benefit-Cost Calculations. Shadow Prices. CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 3 Total factor productivity Total factor productivity (TFP) Output per combined factor input. TFP grow.th is a measure of technical progress. TFP fell almost 1% yearly in the Soviet Union, 1971-1985. Productivity growth “is almost everything . . . in the long run.” (Krugman) U.S. , Canada, Japan, & Western Europe real growth in GNP per capita > 1% annually from mid-19th century to 2000. CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 4 Absorptive capacity Absorptive capacity The ability of an economy to profitably utilize additional capital. This ability depends on the availability of complementary factors. CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 5 Sources of growth DCs & LDCs In West & Japan, econometric studies showed that capital per worker-hour explained less than half of output per worker-hour. In LDCs, capital per worker-hour explained more than half of output per worker-hour. Technical progress relatively important source of growth in DCs and capital accumulation relatively important in LDCs. Hicks: cannot surmise, though, that capital accumulation is of minor importance. Many advances in knowledge are embodied in new capital. CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 6 Residual or technical knowledge Denison & Addison: education, training, advances in knowledge, learning by experience, economies of scale, product variety, improved allocation of resources, reduction in age of capital, & decreases in time lag in applying knowledge. Balogh & Streeten object to elevating residual, converting ignorance to knowledge. CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 7 CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 8 Figure 11-1’s message Reinforces earlier econometric studies indicating capital contributed more than productivity to LDC GDP growth. Sub-Saharan Africa & developing Europe and Central Asia (mostly transitional) had negative productivity growth. World Bank expects productivity to contribute more than capital to growth in East Asia & Pacific, 2005-2015. CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 9 Learning by doing Technical change is a prolonged process based on experience and problem solving, that is, doing, using and interacting. Learning curve measures how much labor productivity increases with cumulative experience. U.S. Air Force engineers assume constant relative decline in labor per airframe as number produced increases (but not to infinity). Stiglitz – markets for information imperfect, with spillovers and public-goods character. CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 10 Inputs and technical knowledge Growth as process of increase in inputs: if human capital is an input then most of growth explained by increases in inputs (Schultz, Jorgenson, Griliches). Cost of technical knowledge: cost of search; efficiency of given technology varies from country to country; thus T (technology) in production function is not a constant. CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 11 Research, invention, development & innovation Basic research. Applied research. Invention: Devising new methods & products. Innovation: Embodiment in commercial practice of a new idea or invention. cont CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 12 Research, invention, development & innovation (cont) Organized R&D (only a part of actual research & development). Monopolist appropriates large proportion of gains from R&D. Advantages of “relative backwardness” and technological followership. CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 13 Computers, electronics, & information & communications technology (ICT) Solow in 1987: “You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.” True for most major innovations (steam engine, railroad, electricity, computers) – substantial time lag between introduction and widespread diffusion. CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 14 Can ICT provide LDCs with short cut to prosperity by bypassing phases of development? (Pohjola 2001) CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 15 ICT & increased productivity ICT requires three new directions to benefit productivity. (David, 2001): 1/ availability of a growing range of purpose-built and task-specific information technologies (e.g. supermarket scanners and other data logging devices). 2/ networking capabilities and networked environment reconfiguring work organization. 3/ internet technology introduces a new class of organization-wide data processing applications. CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 16 Contribution of ICT to GDP percapita growth in the U.S. (not counting increased TFP of non-ICT sectors from ICT-facilitated work reorganization & knowledge spillovers). 1974-1990 0.69 percentage points yearly. 1991-1995 0.79 percentage points yearly. 1996-2000 1.86 percentage points yearly. CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 17 Low-cost ICT improves . . . Allocative efficiency by minimizing input cost per output. Technical efficiency by cutting costs by better access to factor and product markets (mobile phones reduce information costs). Economies of larger-scale production by breaking labor & capital constraints. CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 18 Explosion of cellular phone technology India 56 million cellular phone users by end of 2004. Expected to reach > 130 million by 2008. Continued growth for many years. Telecommunications deregulation in 1990s facilitated growth. India, China, & other LDCs can leapfrog Western landline telephone technology. CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 19 Sachs’ (2000) division of world Technological innovators (Schumpeterian entrepreneurs, discussed in Chapter 12). Most of OECD plus Taiwan (15% of world’s population). Technological adapters (Addison – LDCs’ imitation of DCs and increased education, major contributors to TFP). Mexico, Costa Rica, Argentina, Chile, Tunisia, South Africa, Israel, most of India, Singapore, Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, coastal China, Baltic states, Russia (near St. Petersberg), East-Central Europe (50% of world’s population). Technologically excluded (rest of world). CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 20 With some exceptions (not all blue are innovators, much of India is adaptive, etc.), blue-colored (high-income) nations are technological innovators, red & green (middle-income) nations are adapters, & yellow (low-income) nations are excluded. CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 21 Rapid ICT growth Moore’s Law: doubling of computer capacity & halving of computer & software prices every 2 years. Pohjola: if auto technical progress were at the same rate as computer technical progress (1958-94), price of car today would be $5! CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 22 CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 23 CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 24 ICT growth in Asia Half OECD ICT imports from nonOECD countries, primarily in Asia, but largely from multinational corporations with headquarters in OECD countries. Innovators in Asia. Cellular technology in Bangladesh benefits petty traders haggling with middlemen. CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 25 Investment criteria Suppose society has a given amount of resources to invest. Should society invest in steel, fertilizer, schools, computers, agricultural extension, or what? Maximizing a project’s labor intensity is not a sound investment criterion. CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 26 Social benefit-cost analysis more comprehensive The net present value (V) of the stream of benefits and costs is calculated as V = B0 – C0 + (B1 – C1)/ (1 + r) + (B2 – C2)/(1 + r)2 +. . . (BT – CT)/(1 + r)T where B is social benefits, C is social costs, r is the social discount rate, t is time, and T the life of the investment project. CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 27 CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 28 Interest on capital . . . Reflects discount of future income relative to present income. Capital invested now represents potential for higher income in the future. $ in future is never worth today’s $. CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 29 What discount rate to use? Current interest rate. Or if distorted, choose a discount rate so that present value of net income stream is equal to the value of capital invested (Equation 11-1). With numerous projects, can pool risk. Still, risk averse decision makers can place less value on probability distributions with substantial risk or wide dispersion around the mean. CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 30 CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 31 Differences between social & private benefit-cost calculations External economies. Distributional weights. Indivisibilities. Monopoly. Saving & reinvestment. Factor price distortions (corrected by using shadow prices). CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 32 What should Dakha, Bangladesh authorities consider when building an underground railway? Can estimate capital outlays as expect outlays to take place. Net social benefits should > or = net social costs. Benefits include not only total receipts but also externalities. CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 33 External benefits & costs (not included in receipts) . . . Price people willing to pay for alternative transport (auto, taxi, bus, bicycle, & rickshaw) + time, comfort, & safety benefits – fare payments. Environmental benefits (reduced pollution & congestion) & costs (disruption of neighborhoods, pollution & inconvenience of initial construction). CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 34 Shadow prices Shadow prices: The adjustment of prices to take account of differences between social cost-benefit and private costbenefit calculations. Wouldn’t it be easier for LDC governments to change foreign exchange rates, interest rates, wages, and other prices to equilibrium prices than to use scarce personnel to calculate shadow prices in these markets? CHAPTER 11 ©E.Wayne Nafziger Development Economics 35