Resources and Capabilities

advertisement

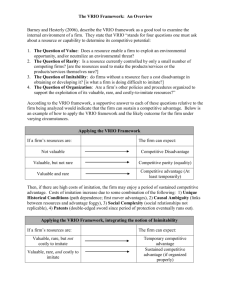

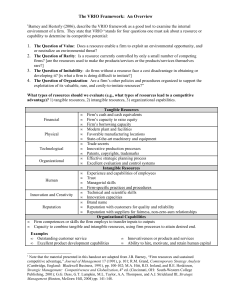

国际企业管理 4 Leveraging Resources and Capabilities Part II: 资源与能力的视角 国际企业管理4 朱吉庆 朱吉庆 博士 讲师 harveyzjq@126.com Outline • Understanding resources and capabilities • Resources, capabilities, and the value chain • The VRIO framework • Debates and extensions • Implications for strategists 4–2 Competing on Resources • Opening Case: Consider the intense competitive conditions in the airline industry. The industry-based view suggests that all firms “stuck” in this industry are likely to suffer. • Question: How can firms like Ryanair (Opening Case) and Southwest Airlines consistently do so well in such an unattractive industry even during periods of recession? 4–3 Competing on Resources (cont’d) • Answer: There must be resources and capabilities specific to successful firms like Southwest and Ryanair that are not shared by their unsuccessful competitors in the same industry. • This insight has been developed into a resourcebased view, which has emerged as one of the three leading perspectives on strategy. • This is the heart of this chapter 4–4 Competing on Resources (cont’d) • Focus of the industry-based view: How “average” firms within an industry compete. • Focus of the resource-based view: How individual firms differ from each other within an industry and can outperform the industry average consistently and significantly. 4–5 Resources and Capabilities • The Resource-based View A firm consists of a bundle of productive resources and capabilities. Resources – The tangible and intangible assets a firm uses to choose and implement its strategies. Capabilities – The skills a firm can use to bring its resources to bear. This book follows leading resource-based theorists such as J. Barney, D. Collis, and C. Montgomery, by using the two terms, “resources” and “capabilities,” interchangeably and often in parallel. 4–6 Resources and Capabilities • Tangible Resources and capabilities that are observable and easily quantified Broadly organized in four categories: Financial Physical Technological Organizational • Intangible Resources and capabilities not easily observed or difficult (or impossible) to quantify Examples include: Human Innovation Reputational 4–7 Examples of Resources and Capabilities Sources: Adapted from (1) J. Barney, 1991, Firm resources and sustained competitive advantage (p. 101), Journal of Management, 17: 101; (2) R. Grant, 1991, Contemporary Strategy Analysis (pp. 100–104), Cambridge, UK: Blackwell; (3) R. Hall, 1992, The strategic analysis of intangible resources (pp. 136–139), Strategic Management Journal, 13: 135–144. Table 3.1 4–8 Resources, Capabilities, and the Value Chain • Value Chain The functional activities within the firm that create value in the goods and services produced • Components of the Value Chain Primary activities Are directly associated with the development, production, and distribution of goods and services. Support activities Assist in the accomplishment of primary activities. 4–9 The Value Chain Panel A. An example of value chain with firm boundaries Figure 3.1 4–10 The Value Chain (cont’d) Panel B. An example of value chain with some outsourcing Figure 3.1 cont’d 4–11 Value Chain Analysis • Shows how a bundle of resources and capabilities come together to add value. Forces strategists to think about firm resources and capabilities at a micro-activity-based level. The key is to examine whether the firm has the resources and capabilities to perform a particular activity in a manner superior to competitors. Requires that strategists ascertain a firm’s strengths and weaknesses on an activity-by-activity basis, relative to rivals, in a SWOT analysis. 4–12 A Two-Stage Decision Model in Value Chain Analysis Figure 3.2 4–13 Outsourcing • Turning over all or part of an organizational activity to an outside supplier which will perform it on behalf of the focal firm. Value-adding activities can be geographically dispersed to take advantage of the best locations to perform certain activities. Outsourcing manufacturing to China Outsourcing IT/BPO activities to India 4–14 A Geographically Dispersed Global Value Chain: How General Electric Medical Systems Produces the Proteus Radiographic System Source: Adapted from T. Khanna & J. Weber, 2002, General Electric Medical Systems, 2002, Harvard Business School case 702–428. Figure 3.3 4–15 The VRIO Framework • VRIO An analysis of the “sticky” nature of resources and capabilities of a firm and the difficulty of their replication elsewhere. • Two Key Assumptions: Resource heterogeneity Each firm has a unique combination of resources and capabilities such that no two firms are “twins.” Resource immobility Resources and capabilities unique to one firm cannot easily migrate to competing firms. 4–16 The VRIO Framework: Features of a Resource or Capability Sources: Adapted from (1) J. Barney, 2002, Gaining and Sustaining Competitive Advantage, 2nd ed. (p. 173), Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall; (2) R. Hoskisson, M. Hitt, & R. D. Ireland, 2004, Competing for Advantage (p. 118), Cincinnati: Thomson South-Western. Table 3.2 4–17 The VRIO Framework: Value • The Question of Value Only value-adding resources can lead to competitive advantage, whereas non-value-adding capabilities may lead to competitive disadvantage. If firms do not shed non-value-adding resources and capabilities, they are likely to suffer below-average performance or become extinct (e.g., IBM). • Overall, the search for valuable resources and capabilities is an ever present challenge for virtually all firms. 4–18 The VRIO Framework: Rarity • The Question of Rarity Valuable common resources and capabilities can lead to competitive parity but no advantage (e.g., airline aircraft). Valuable rare resources and capabilities can provide, at best, temporary competitive advantage (e.g., Ford pricing) Resources and abilities that add value in new areas needed to keep up with the competition (benchmarking). • Once competitors develop equal abilities, then no unique and distinctive capability remains on which to build a competitive advantage. 4–19 The VRIO Framework: Imitability • The Question of Imitability Valuable and rare resources and capabilities are a source of competitive advantage only if competitors have a difficult time imitating them. Imitation of tangible resources (such as plants, software, or trucking fleet) is easy. Imitation of intangible resources (knowledge, managerial talents, and organizational culture) is much more difficult. Some resources are impossible to imitate 4–20 The VRIO Framework: Imitability (cont’d) • Why is imitation so difficult? Time compression diseconomies: Inability to acquire in a short period of time rivals’ resources and capabilities over a long history (SIA 3.2: Mercedes’ failure in learning and practicing the Japanese capabilities of “design to cost”) Path dependencies: History matters Causal ambiguity: What really causes the success of certain firms? Nobody really knows! 4–21 The VRIO Framework: Organization • The Question of Organization How is a firm organized to develop and leverage the full potential of its resources and capabilities? • A More Fundamental Question Why do firms exist? In other words, why do people organize firms? Firms exist to develop and leverage resources and capabilities better than individuals could. • Complementary Assets: Star power + other talents • Social Complexity: Movie production 4–22 The VRIO Framework: Overview • Because resources and capabilities cannot be evaluated in isolation, the VRIO framework presents four interconnected and increasingly difficult hurdles for them to become a source of sustainable competitive advantage. 4–23 Lessons from the VRIO Framework • Build the firm’s resources and capabilities strengths before beginning the search for the most attractive industry or segment. • Imitation is not a successful strategy—creating new ways of adding value forces competitors to play the best performing firm’s game. • Competitive advantage does not last forever—strategic foresight is necessary to anticipate needs and move early to build resources and capabilities for future competition. 4–24 Debates and Extensions • Firm- versus Industry-Specific Determinants of Performance: Both views are complementary to each other • Static Resources versus Dynamic Capabilities Table 3.3 • Rent Generation versus Appropriation: Who gets what? • Domestic Resources versus International Capabilities: Are they the same? 4–25 Dynamic Capabilities in Slow- and Fast-Moving Industries Sources: Adapted from (1) K. Eisenhardt & J. Martin, 2000, Dynamic capabilities: What are they? Strategic Management Journal, 21: 1105–1121; (2) G. Pisano, 1994, Knowledge, integration, and the locus of learning, Strategic Management Journal, 15: 85–100. Table 3.3 4–26 Implications for Strategists • The strategic imperative is to focus on identifying the resources and capabilities that really count and developing new ones. • Strategists need to focus on when, where, and how resources and capabilities are useful. A fundamental challenge is how to do this, not just once or every now and then, but consistently. • The resource-based view offers a set of answers to the four fundamental questions in strategy. 4–27 Implications for Strategists: Fundamental Questions to Consider • Why do firms differ? The assumption of resource heterogeneity – that is, every firm is unique in its bundle of resources and capabilities – directly addresses this question. • How do firms behave? The answer boils down to how they take advantage of their strengths embodied in resources and capabilities and overcome their weaknesses. 4–28 Implications for Strategists: Fundamental Questions to Consider (cont’d) • What determines the scope of the firm? Value chain analysis suggests that the scope of the firm is determined by how a firm performs different value-adding activities relative to rivals. Managers often fail to assess them relative to competitors, resulting in an unnecessarily broad scope with some mediocre units. • What determines the international success and failure of firms? The resource-based view identifies firm-specific resources and capabilities as the crucial determinants. 4–29 Key Terms agency problem agents business process outsourcing (BPO) capabilities causal ambiguity complementary assets core competencies corporate governance direct duplication dynamic capabilities financial resources and capabilities human resources and capabilities innovation resources and capabilities 4–30