The triumph of traditional politics with its corrupting effects

upon the masses is occasioned by the failure of the middle

and upper classes to govern the community.

--Gising Barangay Movement Inc

GISING BARANGAY!

I.

Barangays: Our Small Republics

II.

Critical Tasks of Barangay Governance

III. 8-Point Agenda for Empowerment

IV. Keep Issues Alive, People Awake

(The Pulong-Pulong)

V.

GBM Organization Structure

Hierarchy

Operating Policy

Immediate Objective of the Chapter

A Task Force

I.

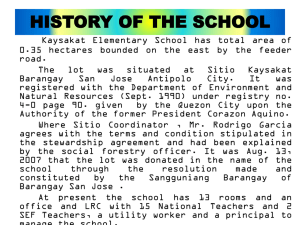

BARANGAYS: OUR SMALL REPUBLICS

The Barangay is a small republic.

It has territory, people, government,

and, though limited, sovereignty.

As the home of every sovereign Filipino,

its voters provide legitimacy to government

and authority to public servants on all levels.

Every precinct is located in it; every vote cast in it.

The Big Philippine Republic draws its life force, direction and political will from these

small barangay republics. To neglect even one barangay is to weaken the chain of close

to 42,000 small barangay republics that make up our Big Republic. For it is the basic

unit of our political, economic, and social system.

A Public Corporation

The barangay is a public corporation representing the

interests of its constituents. It may adopt its own logo,

sue or be sued, enter into contracts, have joint ventures

with other barangays or with public and private

institutions, lend or borrow money, acquire or sell

property, invest in or establish enterprises, and share

benefits from its earnings with its inhabitants.

Its authorized capital is subscribed by stockholders (its

constituents) in the form of tax payments – which are

their equity in its operation as an enterprise, entitling

them to dividends in the form of services and other

socioeconomic benefits.

An Economy

The barangay is an economy – with land, labor, and

capital. Except in urban centers, its land comprises

several square-kilometers with assorted physical and

strategic attributes or assets that can be developed for

industry, agriculture, tourism, and other profitable uses.

Developing or capitalizing these assets would generate

new wealth, employment, and livelihood. It would open

opportunities, improve standards of living, and raise

quality of life. It would contribute not only to the gross

domestic product but also to our gross national

happiness.

The barangay’s labor force consists of people in diverse occupations, professions, or

fields of endeavor – in arts and crafts, in services, in enterprises. In addition to its

revenues, its capital includes the equity, holdings, or possessions of its stakeholders,

the barangaynons.

Unique Government

Before Congress enacted the Local Code Government of

1991, the barangay was simply an appendage to the

municipality or city called “barrio” -- a quasi-municipal

entity with no powers or resources at its command.

This changed radically when the Code made it a fullfledged government and the primary level of our

political structure -- with three branches, powers, and

resources.

As such, it acquired the power to legislate or pass

ordinances, levy taxes or fees, regulate public affairs

(police power), and exercise eminent domain (over

private property for public use). Hence, it is no longer an

insignificant extension of a city or municipality.

Moreover, the Code vested it with a unique mode of governance, distinct from the

upper levels (municipal to national). Instead of representative democracy, it has a

direct democracy. Instead of presidential it has a parliamentary form, complete with

the power of Recall (to remove officials for loss of confidence).

This set up resembles the system in Switzerland and Israel, where direct democracy

below complements representative democracy above. It enables the citizens to

manage their local affairs directly, not indirectly through representatives. They do so

as members of its legislative governing body -- the Barangay Assembly, which is a

parliament except in name.

Chairman, Not Kapitan

Consistent with this parliamentary form of government, the

Code changed the barangay leader’s title to “Chairman” -- no

longer “Kapitan” which is a position of command over troops

or subordinates. The term “kapitan” was derived from the

days of the Guardia Civil when barrios were commanded by

actual captains or lieutenants of the Spanish Monarchy.

It was good that the Code did this, because too many

barangay leaders fancied themselves as real “captains” or

commanders, thinking they were “little monarchs.” Others

thought they were “little presidents” because under the

presidential form of government the structure was

monolithic, starting at the top with the president as

commander-in-chief.

But no campaign was ever undertaken to inform the people of these changes. No

one told the barangays about their unique form of government; that their leaders

were not “little monarchs” or “little presidents” but “little prime ministers;” that they

serve only as first among equals; that their prime duty is to preside over their peers,

not order them around or abuse their resources. No one explained that the people are

not their subordinates but their principals – or, as P-Noy prefers to say, their Boss.

To this day, barangay leaders continue to call themselves Kapitan or Kapitana, ignorant

of the fact that they are not the superiors but rather the servant of their constituents.

It is a misnomer that is further perpetuated by the constituents, their Boss, who play

along and call them that too. In fact, the proper term is “chairman” or “punong

barangay.”

No one seems to see irony in having sovereign citizens commanded or subordinated to

their public servants

Another fact underscores the parliamentary nature of barangay governance: unlike

the presidential mode at upper levels, which operate under the principle of separation

of powers (separate branches, separate heads), the three branches of the barangay

government are headed by one and the same official: its chairman. It is a distinctive

feature of a parliamentary form of government, although the usual practice combines

only the executive and legislative branches.

All this has transformed our political system from what used to be a monolithic or

unitary structure from top to bottom into a split-level or dual structure: the upper and

lower levels having different modes of governance.

The stability of our Republic hinges upon the extent to which both levels perform their

tasks in accordance with the principle of subsidiarity – which requires that any task

that can be done at the lower level should not be performed by or delegated to the

upper level.

An Awakened Citizenry: Our Best Hope

Filipinos need to know the nature and powers of the

barangay as a government-corporation-economy so they

can perform their role in its complex operation.

Otherwise they will continue to be manipulated, their

community’s resources milked dry by traditional

politicians, or trapos, who play at governance while

mismanaging its corporate and economic interests.

Only responsible citizens can make the barangay government operate properly and

reform the political system that has been corrupted by wrongful practices. Only if they

take part in its democratic processes can they, as sovereign citizens, enforce

transparency, accountability, and responsible governance at the grassroots -- on which

the foundation of our Big Republic is built.

Pinatubo, di pinatulo: the fundamental process by which democracy grows.

Essential Role of the Elite

Unless the stakeholders of this barangay corporation are

attentive, they cannot expect its assets to be managed

efficiently or to yield optimal dividends for everyone.

They own or work the land and other resources of the

barangay economy; they must develop its potentials,

expand its wealth, and thus create opportunities for all.

But none of this will happen without the participation of the middle and upper classes

– the knowledgeable, influential, and well-off citizens. Good governance is simply

another term for “sound management” and it is not possible without them. Only if

they participate is it possible to reform attitudes, values, and corrupt practices in the

barangay – our basic political, social, and economic unit. The larger society is nothing

but clusters of barangays.

Thus, we say:

Governance is everybody’s business; if you’re not involved, you can’t expect good

governance! #

LET EVERY MAN STATE WHAT KIND OF GOVERNMENT

WOULD COMMAND HIS RESPECT, AND THAT WILL BE THE

FIRST STEP TOWARD OBTAINING IT.

--Henry David Thoreau

II.

The Critical Tasks of Barangay Governance

Barangay officials have many tasks and responsibilities. They have

both the authority and the resources with which to perform these.

It is not the GBM’s intention to hound them on every detail. But

we do need to make sure that the tasks affecting the common

good intimately are performed, tasks that need critical attention

because of habitual neglect and corrupt practices.

A. EXECUTIVE BRANCH: Office of the Chairman/Punong Barangay

Barangays are allowed to design and implement their own organizational structure

and staffing pattern based on their priorities, service requirements, and financial

capability. Large barangays need sophisticated management systems, small ones

simpler. (Section 76-77, R.A. 7160)

This could be a simple task if officials learn to avail of expert advice or assistance

from their knowledgeable residents or institutions like universities or development

institutes nearby. It is not only allowed; it is encouraged. They can call on external

agencies/ management experts for technical and other assistance.

[Section 107 (d)]

Cost-benefit ratios, for example, would improve with imaginative mobilization of

resources, human and non-human. There are companies with equipment, facilities, or

experts that can lend assistance; after all, they are corporate citizens of the barangay.

Many highly skilled professionals live in the neighborhoods, but they are

unmotivated or simply ignored. Service clubs like Rotary, Jaycees, Boy and Girl

Scouts, and civil society groups could also help. Involving them in community

service would reduce operating costs, while raising community pride and sense of

ownership. Volunteerism (bayanihan-style collaboration) is disappearing

because barangays don’t encourage it. In other countries, volunteers direct traffic,

handle day-care services, even fight fires or deliver the mail. Why not in the

barangay?

Critical Tasks:

1.

A periodic inventory of property and audit of funds is important -- to protect

them, to account for them, to pinpoint accountability, and to put records in

order, especially at the end of each term.

This should include Katipunan ng Kabataan and Sangguniang Kabataan – whose

performance has been increasingly criticized.

Members of the Philippine Institute of Certified Public Accountants (PICPA) reside in the

barangay. They could well assist in this task. It’s their neighborhood.

2.

Physical plant, equipment, and facilities need regular inspection

Many day-care centers and libraries are inoperative,

some used as storerooms. Public comfort rooms are

filthy, reading rooms are badly lighted or not at all. Playground equipment, if any, are run down or don’t serve

varying age groups. Many have no street signs or

garbage receptacles.

(Cf. Section 17, R.A. 7160)

It is revealing that despite its affordability today, a computer is a rarity in barangay

offices. This says a lot about the proficiency or sophistication of barangay officials.

And yet, they have residents who are active members of

the Philippine Institute of Architects, United Architects of

the Philippines, or the Philippine Institute of Civil

Engineers. There are also technology training centers.

But they might as well not be there.

3.

Information systems need upgrading including public

stands or bulletin boards in strategic places for

ordinances, reports, lists, or a vicinity map.

The law requires certain reports and documents to be posted in at least three (3)

prominent locations. Few barangays bother with these transparency and

accountability requirements. Their failure to comply keeps constituents in the

dark about operations and expenditures -- breeding misuse, abuse, or corruption.

(Section 399, R.A. 7160; Article 122 (3) (xi), Implementing Rules and Regulations; and

No. 100 of the Primer on Barangay Budgeting of the DBM)

Within the Barangay Hall, various lists, periodically updated, are supposed to be

maintained and available on demand, especially the roster of Barangay Assembly

members and the Katipunan ng Kabataan, and ordinances.

A complete list of inhabitants is essential for determining who are entitled to assistance. Its

absence creates injustice: illegal residents or flying voters crowd out the legitimate and

deprive them of their rights, while unlisted residents cannot avail of benefits. And the

address of wanted persons or crime suspects cannot be checked. Badly-governed

barangays are a boon to criminals!

4.

Officials must file various disclosure statements

Assets, Liabilities and Net Worth, Personal Data, Financial

and Business Interests, Relatives within the fourth civil

degree of consanguinity or affinity, and so on. (Sec. 51,

R.A.7160; Art. 104, Implementing Rules & Regulations).

Failure to do so violates laws against conflict of interest or graft and get away with it.

Without anyone checking, no one bothers to comply. (Section 89)

There is a general attitude that encourages non-compliance: Filipino reticence about

inquiring into the conduct of their officials; a hang-over from colonial days when no one

could question even a Capitan or Teniente del Barrio.

5.

The Barangay Secretary and the Barangay Treasurer

must be well qualified.

The Sanggunian is supposed to screen them before

confirming their appointment. (Section 394-395, R.A.

7160)

As representatives of the community, kagawads ought to ascertain the suitability or

fitness of these officers. Their performance affects community interests directly; so the

inhabitants must have confidence in them or be aware of their ability.

6.

THE BARANGAY SECRETARY

must be an actual resident and a qualified voter of

the barangay. No civil service eligibility is required

but he or she cannot be a relative of the Chairman

within the fourth civil degree of consanguinity or

affinity.

(Section 394.)

Among others, the Secretary:

a.

Keeps minutes and records of the Sangguniang Barangay and Barangay Assembly meetings;

b.

Maintains an up-to-date roster of members of the Barangay Assembly, posting the same in

conspicuous places;

c.

Maintains a record of all inhabitants containing name, address, place and date of birth, sex,

civil status, citizenship, occupation, and other data;

d.

Submits reports on the actual number of residents as often as required by the Sanggunian;

e.

Issues notices of meetings – especially of the Barangay Assembly, which must be in writing

and issued at least one week in advance;

f.

Attends and journalizes meetings of the Sanggunian, Barangay Assembly, the Lupon,

Barangay Development Council; and refers matters to committees and officials having

responsibility for them.

This position has heavy responsibility for multiple operations. Its duties span the gamut of

executive, legislative and judicial operations. With growing populations and diverse activities to

be monitored, recorded and followed up, the workload is heavy.

Good education, reporting skills, database management, organizing experience, and methodical habits

are imperative for performing these.

7.

THE BARANGAY TREASURER

must be an actual resident and qualified voter of the

barangay. No civil service eligibility is required but

cannot be a relative of the Chairman within the fourth

civil degree of consanguinity or affinity. A bond of up to

ten thousand pesos is required, to be paid by the

barangay.

(Section 395, R.A. 7160)

He is the chief financial officer of the barangay as a government and corporation,

responsible for all financial transactions within the jurisdiction. There are taxes, fees

and licenses to compute and collect, properties to account for, assets to safeguard,

liabilities to tend, and regular reports to prepare.

Duties and responsibilities include:

a.

Custody of funds/properties, properly handling, recording and accounting for them;

b.

Collection and issuance of official receipts for taxes, fees, contributions -- depositing

same in the barangay’s account;

c.

Disbursing funds in accordance with specified procedures;

d.

Preparing reports, ensuring that same are furnished or made available to Barangay

Assembly members and the general public;

e.

Certifying as to the availability of funds;

f.

Preparing Quarterly Budget Accountability Reports on Actual Income and on Financial

Operations (No. 97, DBM Primer on Barangay Budgeting);

g.

Examining books of enterprises with tax obligations.

Needless to say, attention to detail, a systems-orientation, and integrity are imperative here.

Millions in cash and other assets are pilfered or wasted in barangays where the

Treasurer is unreliable or corrupt: improper cash advances, no liquidations,

kickbacks from contractors, commissions from purchases, unauthorized property

disposal, equipment/supplies pilfered, appliances/spare parts spirited away, even

light bulbs and doorknobs. That’s why inventories and audits are a must!

Because of such irregularities, many barangays start a new term without equipment,

supplies, or money. It happens where constituents are negligent and inattentive to

their public corporation.

8.

BARANGAY DEVELOPMENT COUNCIL (BDC), ITS NGO MEMBERS

As the nerve center of planning and development for the neighborhoods, this

unit needs utmost attention.

Unless it is organized and operational in accordance with law, the community

cannot expect to have a rational plan, a set of well-defined priorities, or a

sensible pattern of development. Development is then reduced to a game of

chance, its infrastructure and services subject to the chairman’s whims.

Barangays with malfunctioning BDC are easy to spot: no proper drainage, no sidewalks

or walkways where needed, no paving for streets except where favored persons reside,

poor sanitation, filthy markets, and squatters everywhere.

The BDC cannot do a competent job without an active NGO sector in it. It is

supposed to comprise at least one-fourth of its membership. Since there are ten

basic members from the government (seven kagawads, SK chairman, barangay

chairman, and congressman’s representative); there should be at least three (3)

NGO representatives – meaning, it can be more. NGOs are corporate citizens and

should conduct themselves accordingly.

There is a prescribed procedure for selecting the NGO members. Its non-observance

accounts for the zoning anarchy in barangays. The Chairman usually just designates

whomever he likes and rarely bothers to convene it. (Section 107-112, R.A. 7160)

Its little-known functions:

a.

Mobilizing the people’s participation in local development efforts,

including the creation of sectoral and functional committees to assist in its

planning and other tasks.

Cooperation and collaboration within the barangay would be a reality instead of

a rarity if this function is operative.

b.

Prepare development plans based on local requirements, especially the

medium-term Comprehensive Multi-Sectoral Development Plan (5 years).

Rarely is this prepared with inputs from different sectors; so it doesn’t reflect the

wishes, aspirations, or priorities of the residents -- deprived of their right to

determine what or how they want their community to become.

c.

Monitor and evaluate the implementation of national or local programs and

projects within the jurisdiction.

Where these cause negative impacts, the BDC is supposed to call the responsible

agency’s attention, along with proposals to mitigate the same. The existence of

sloppy public works in them reflects the failure of this function.

d.

To call upon any official of public agencies with offices within for assistance in

formulating public investment programs or other development plans. [Section

107 (d), R.A. 7160]

Agencies with assorted professionals o board have plenty to contribute to the

quality and fullness of life in the community; but they might as well not be there.

As a result, to judge a barangay by its appearance or ambience today is to conclude

that the professionals who reside in them have poor taste, low standards, and no

concept of civilized community living.

B.

LEGISLATIVE BRANCH: The Sangguniang Barangay

This is the board of directors of the barangay as a corporation, acting on behalf of

its stakeholders/constituents. But many of its responsibilities are neglected for

lack of community oversight. No one bothers to monitor its proceedings. Among

its least performed duties and responsibilities (Section 391-392:

1.

Adopt measures to prevent and control the proliferation of squatters and

mendicants in the barangay.

Not only is this task generally neglected, it is violated with impunity by officials

who connive with corrupt mayors who conspire to multiply squatter-votes.

The public trust is violated, as are the interests of property-holders, where officials

encourage or abet squatting. But citizen apathy condones it!

Citizens should see to it that officials do not make a mockery of the law or the rights of

others. Unless they do, they become part of the problem, tolerating neglect, incompetence,

or corruption.

Neglectful citizens cause slums to sprout and threaten the community with disease from lack of

sanitation, with fire from illegal connections, with criminality from vice or illegal activity, and with

budget deficits for overloading social services.

2.

Conduct regular lectures, programs, or forums on community

issues; establish library and reading rooms; or sponsor wholesome

community programs.

The general neglect of this task has turned our barangays into cultural

wastelands -- hostile to intellectual habits and pursuits, addicted to

nonsense dished out by popular entertainment fare, and an easy prey to

media that cater to the baser instincts of undereducated people.

In fact, there are men and women of science, technology, and the arts in the neighborhoods.

There are educators and culture vultures, inventors and engineering practitioners, artists, food

technologists, medical professionals, and institutions in them.

With them, Barangay compounds would be buzzing with lectures, demonstrations, exhibits,

and learning activities. In most barangays, there are talents, experts, or institutions!

3.

Initiate the establishment of a barangay high school

where feasible, or of a non-formal education center.

Preoccupation with politics, abetted by selfish pursuits, has

resulted in the gross neglect of education. Barangay governance should have an

educative, civilizing role. This is where the non-government sector must help.

4.

Establish, organize, or promote cooperative enterprises that improve the economic

condition and well-being of the residents.

Barangays may invest in joint ventures with other

barangays or the private sector – e.g. pooling resources

for a water system, a milling facility or warehouse for

farmers, a display or promo center for the arts and crafts

of their talented residents, capitalize production or

processing projects, even establish a cooperative.

No economy, small or large, grows or produces benefits without earnest development. The

barangay economy would acquire vigor with cooperatives and micro-finance enterprises.

5.

Solicit funds, materials and voluntary labor for

public works and cooperative enterprises

from residents, land owners, producers and

merchants in the barangay.

Barangays are encouraged to solicit financial, technical, and advisory assistance

from internal or external sources. Among many sources: grants-in-aid from

foundations or aid agencies, business contributions, NGOs, and philanthropists

including expatriates or OFWs who would help if requested by their community

of origin. But this does not happen because their reliance on the IRA, pork barrel

subsidies, and political patronage.

6.

Hold tax-exempt fund-raising activities

without need of securing permits from

external agencies.

The internal revenue allotment (IRA) is only one of many revenue sources. But

they don’t bother to develop other sources to augment their income.

There are corporate citizens, development institutions and NGOs within their

jurisdiction that could help develop revenue-earning projects such as commercial

tree planting, crop growing, handicrafts, apparel and textile production,

carpentry or metal works, cooperative farming, livelihood from tourism and

recreation activities, recycling, and the like.

Everyone in the neighborhoods dreams of projects big and small. As a government and

corporation, the barangay can help make their dreams a reality. But the habit of

sucking up to the Mayor or Congressman for projects kills local initiative and

productivity even as it corrupts the polity.

Barangay officials who rely upon the mayor or congressman (especially if the

latter is a relative or party boss) burden the community with political

indebtedness and the negative effects of patronage, rendering it vulnerable to

electoral manipulation.

7.

Post ordinances and financial reports for the

information of the public.

This has been dealt with earlier. It should be noted also

that the budget is an Ordinance. It should be posted for

all to see and not be treated like a state secret.

8.

Accredit non-government organizations to ensure that they will be

included in the line-up of the Barangay Development Council -- and thus be

able to contribute to the community’s development.

No barangay seems aware of this task. To compound the problem, no NGO seems

eager to get accredited; even church groups are NGOs. The net effect is to

deprive the community of the benefits that NGOs can bring.

This is a symmetrical problem involving both the government and the NGO sectors as

equally non-performing.

IN SUM

Of the 24 enumerated powers, duties, and functions of the

Sangguniang Barangay, these eight tasks are frequently

overlooked because the officials are focused on the next

elections, not on the next generation.

Left to themselves, without citizen oversight, they pursue

personal agendas. Unhampered by citizen interference, they

turn public service into self-service. Thus, it is no surprise that

they’re preoccupied with public works yielding rich kickbacks,

with year-round politicking, with lakbay-aral outings, and

other activities that build political careers but trash the

common good.

C.

BARANGAY ASSEMBLY: Supreme Governing Body,

The Local Parliament

The belittling and neglect of this local parliament has prevented our society from

attaining political maturity, or democracy from becoming a way of life at the

grassroots.

“That government is strongest of which every man feels himself a part,” wrote Thomas

Jefferson over two centuries ago. He was right.

Our republic is weak because Filipinos don’t feel they are part of government. In

their view, the government is owned by the politicians. In turn, the politicos treat

government like a personal household. Being Ama or Ina ng Lipunan enables

them to manipulate the people (household members) as a parent manipulates

his children.

Thus, although every Filipino has a formal and official role in governing his

community, his role is trivialized, devalued by his ignorance of it. This role is his

membership in the Barangay Assembly, the local parliament. He is a member- ofparliament in small letters. But so far it is a meaningless membership because it

does not conduct business formally as befits an assembly of sovereign citizens. It

is marginalized, its powers arrogated by the Chairman and the Sanggunian.

This Assembly is the gathering of the principals (owners/stockholders) of the

corporation. They are the sovereign citizens who create government and vest the

officials with authority. They are not mere representatives -- as kagawads,

congressmen, or senators are.

The citizens are the real constituents. If they convene and are in session, they are

literally a Constituent Assembly with an all-inclusive membership. Thus, it is an

official version of people power; it exemplifies participatory or direct democracy.

Whatever decision or resolution it passes is the voice of citizen sovereignty.

Unfortunately, neither the officials nor the people who are its members

comprehend the essence of this unique institution. No one tells them that this is

“the forum wherein the collective views of the people may be expressed,

crystallized, and considered” (Section 384, R.A. 7160). No one underscores its

power as a legislative governing body (a parliament). No one tells them that:

One:

It is supposed to initiate legislation for the Sanggunian to adopt.

(Section 398)

This means it is part of the barangay’s legislative process, whereby its citizens may

propose ordinances or measures for their own and the common good’s welfare.

Two:

It is mandated to hear and pass upon the reports of the Sanggunian

concerning its activities and finances.

To “hear and pass” means to be informed and then to consider, deliberate on, and

decide what to do with the information: power to confirm or reject. But people don’t

understand this, thinking they are powerless and not a part of government.

Three:

It decides on the adoption of Initiative as a legal process whereby the

constituents directly propose, enact, or amend an ordinance. (Sec. 120127)

This is a a largely neglected power. Instead of filing a petition or proposal with the

government of which we are a part, we go to the media and poison the atmosphere

with views that inflame or undermine government but resolve nothing.

In fact, we can discipline or remove officials for loss of confidence through the process

of Recall -- an essential feature of a parliamentary form of government. ((Sec 69-75)

Importance to our Democracy

First, this Barangay Asembly is the largest organization in every community, the largest

formal gathering of citizens since it includes everyone 15 years old and above. As such,

it makes Philippine democracy at the grassroots truly inclusive, community-based, and

participatory, not just representational.

Second, it is the only venue where an ordinary Filipino speaks with a voice equal to

everyone’s in an official forum -- to petition or make demands, to set standards of

official conduct, to define priorities, or to call for new laws and ordinances.

Our failure to express or assert ourselves here has caused us to confine our

sovereignty to the simple act of voting every three years – an act that is often

negated by cheating and manipulation, or disregarded by not being counted.

Between elections, we are reduced to spectators, blithely manipulated by an

oligarchy, unaware that in fact only we can checkmate the oligarchs.

Why? Because the barangay chairman heads all three branches and no one

within can check him, since every employee is his subordinate. Only if we

assemble as the local Constituent Assembly can question him, sanction him, or

initiate disciplinary action against him. If he fails to enforce the

law or hinders its enforcement by nepotism or bad politics

-- as when he suborns squatters for their votes – no one else

can sanction him.

The Barangay Assembly is the check-and-balance mechanism

of the local polity, the grassroots.

We need to convene the Barangay Assembly with seriousness, with dignity, with

ceremony, and parliamentary rules. It doesn’t always need the Barangay

Chairman to convene it. The people can assemble by themselves through a

resolution/petition signed by five (5) percent of its membership. (Section 397).

To activate it is to let true democracy reign at the primal level of our Republic. It

ought to convene often, not only twice a year -- which is the minimum required.

And it should do so at the people’s pleasure, not the chairman’s. Only then

will Filipinos have a hands-on experience of democracy and parliamentary

government.

D.

THE JUDICIAL BRANCH: Lupong Tagapayapa

The Lupon is a unique Filipino social/political invention. It combines tradition,

common sense, and practicality in judicial administration. Consisting of 10 to 20

members, its members are selected as follows:

1.

Anyone residing or working in the barangay, with no legal disqualification, is

eligible if he possesses “integrity, impartiality, independence of mind, sense

of fairness, and reputation for probity”

( Section 399).

2.

Within 15 days after assuming office, the Punong Barangay prepares a notice

to constitute the Lupon, along with the list of nominees who have indicated

their willingness to serve.

3.

The notice and the list must be posted in three (3) conspicuous places for at

least three (3) weeks. Any opposition or recommendation from anyone is

noted and recorded and taken into account in deciding the final appointees.

4.

At the close of the three-week period, the Chairman decides who will be

appointed and issues their written appointment

5.

After taking their oath of office, their names must be posted in three (3)

conspicuous places for the entire duration of their three-year term.

Rare is the barangay that observes this selection process faithfully. As a result, persons

of dubious qualification ,occupation, stature, or integrity are appointed.

The practice of designating sitio and zone leaders automatically as Lupon

members should not be tolerated. Lupon membership shouldn’t be used to

reward supporters or provide income for political allies. Mixing political agenda

with judicial functions is wrong. Lupon members must be non-partisan and

independent-minded.

The Lupon’s functions:

a.

To create and supervise conciliation panels (Pangkat ng Tagapagkasundo)

consisting of three Lupon members per case to handle disputes until they are

resolved;

b.

To meet regularly once a month to address pertinent issues, coordinate with

each other, and exchange views and experiences in resolving disputes; and

c.

In general to arbitrate, mediate, or conciliate disputes.

As simple as these responsibilities may sound, the tasks and processes entailed are

complicated and sensitive. Emotions can run high between contending parties, who

are neighbors. The character and probity of Lupon members must be beyond

reproach.

This dispute-resolution mechanism at the grassroots is actually a throwback to our

pre-Spanish barangays. Cases or disputes in those days were brought before village

wise men who facilitated the process of conciliation. It is a fine way of settling

disputes without going to court, a neighborly way to heal differences and resolve local

issues.

A question arises: Are the wise men and women in barangays being sought out

for appointment to the Lupong Tagapamayapa? The high case-load in our courts

would not be so overwhelming if the Lupons work conscientiously and efficiently.

FINAL NOTE

There are many other concerns in the barangay. The tasks involved in them are

the nuts and bolts of good governance. The extent to which these are performed

adequately and lawfully conditions the conduct of government at upper levels.

All officials at upper levels come from the barangays. The growth or maturity of

our political system -- and democracy itself – depends on whether they perform

their tasks properly at the base of the Republic. As the small barangay republic is,

so is the big Philippine Republic.

It is the overarching mission of the Gising Barangay Movement to make the

barangays a solid base for our Big Republic by awakening the sovereignty of its

citizens and by urging them to assert it for their own betterment. #

Government is everybody’s business; if you’re not involved, you can’t expect

good governance.

--Task Force Good Governance

III.

8-POINT AGENDA FOR EMPOWERMENT

Good governance in the small barangay republic is essential for good governance in

the big Philippine Republic, for it is the prime conditioner of national stability and

progress. Only in the barangay do Filipinos have an official, direct role in government.

It is where they must be empowered if they are to balance the exercise of powers they

delegate to officials at upper levels.

As sovereign citizens, the stakeholders who own or operate the factors of production

in its economy, they must learn to control or take responsibility for its operations. They

must be empowered. To empower them, this 8-Point Agenda is offered .

1.

Get acquainted with your barangay government. It is what makes the

neighborhoods look like they do, feel like they do, and behave like they do.

Visit the Barangay Hall and observe its set up, facilities, and workers. Check the

bulletin boards and see what notices are posted. Get acquainted with the

workers and the officials. Ask for a compilation of local ordinances. Unless the

residents know these, they cannot comply or help enforce them.

Doing so will give a feel of how the barangay is managed -- its sense of duty,

transparency, accountability, and its attitude towards public service. It will help

you decide what you want your local government to do and in what manner.

2.

Enfranchise and empower yourself along with everyone by being active in the

Barangay Assembly. Let it perform its role as the community’s legislative

governing body, or parliament. It is supposed to set the government’s direction,

policy, priorities, standards, and budget -- an unfulfilled role thus far.

Only this Assembly can hold the chairman, the sanggunian, and their appointees

accountable for their performance. As a sovereign citizen, you are a part of its

government and a stakeholder of its corporate holdings – with the Sanggunian as

its board of directors, managing its day-to-day affairs.

The law requires this Assembly to meet at least twice yearly in order “to hear

and pass upon the activities and finances of the barangay” (Section 398, R.A.

7160). This means it should convene as often as necessary, not just twice as is the

practice. It is only through it that a Filipino, apart from his vote, can speak out

officially as a sovereign citizen. Without it, no consensus can arise on public

issues or crystallize the popular will. Opinion polls do not produce consensus.

3.

Insist on professionalizing the operations of the Barangay Development Council.

It is the next most important institution for developing the community. Refer to

Title Six, Sections 106-115, R.A. 7160)

First, review its composition and manner of selecting its members. At least onefourth are supposed to come from civil society. Barangay chairmen rarely comply

with this, depriving the community of the important contributions of NGOs to

local development.

Second, review its performance. The law requires it to prepare a Comprehensive

Multi-sectoral Development Plan. This is supposed to be integrated into the

municipal or city Plan – which in turn are to be incorporated into the upper-level

Plans all the way to the national..

This requirement jibes with the democratic principle that the planning process

must begin from the ground up, instead of from the top as practiced by

autocrats. Without this Plan, officials simply improvise, without a sense of

priorities.

4.

Check the Annual Investment Plan – a very important component of the

Development Plan. Make sure it is a real plan, not just a shopping list of projects

the officials hope will be picked by some mayor or congressman with pork barrel

funds to spare. Without it, a budget cannot be justified.

First, see that this Plan addresses the priorities defined in the Development Plan.

It should be based on a survey of neighborhoods to guide investment priorities.

Second, see that it takes account of the needs of the entire community, not just

the favored sectors, usually the poor and the squatters. Although they deserve

priority treatment, others are also entitled to a share of development even as

they share its costs. Even the wealthy are entitled; they should be encouraged to

expand their businesses so they will pay more taxes and open new opportunities

for livelihood.

Third, help the officials identify productive projects. One way to expand the local

economy is to assist residents with skills or technologies that need a market.

5.

Help professionalize budget preparation, making sure the final version covers the

community’s priorities.

First, insist that it be reviewed by the Barangay Assembly. It should be based on

the approved development and investment plans. Anyone serious about good

governance should not tolerate the practice of giving officials blanket authority

and a blank check to spend as they please. This encourages corruption.

Second, examine the item for personal services. The law allows up to a maximum

of fifty-five percent (55%) of annual income to be allocated for personal services.

Treating this maximum as the minimum is wrong; after allocating the mandatory

share of the sangguniang kabataan (10%) and the Calamity Fund (5%), very little

is left for basic services and development programs.

Barangay officials earn as much as middle managers of business because they

view their allowances as a salary instead of just an allowance. Not good. Barangay

office is meant to provide an opportunity for community service, not

employment or livelihood. People who can’t survive without relying on the

barangay’s limited funds are out of place. They are a burden instead of an asset

to the community, and are susceptible to corruption. They should be earning a

salary somewhere else.

Barangay funds are meant for the community’s development, not for anyone’s

subsistence. Officials who collect maximum allowances for themselves (because

they need a salary), reduce the development fund to a minimum. In effect, they

serve themselves first and the community last.

Their job is to manage this government and public corporation so that the local

economy will expand and produce opportunities for everyone. If they can’t even

manage to earn a livelihood, how can they pretend to create livelihood and other

benefits for the community?

6.

Promote Voluntarism as a way of saving on costs of development.

There are citizens whodesire to help, to give, or to share what they can. They

need an avenue of service. Service to community is the hallmark of a responsible,

caring citizen. It is why there are Jaycees, Lions, Rotarians, Kiwanis, and such.

They wish to serve, to show their concern for the common good. And they like

doing it as volunteers, not for pay. There should be room for altruism.

It shouldn’t be necessary for them to go beyond their barangay to satisfy a desire

to serve or to apply their communitarian ideals. They are important stakeholders

and should be accommodated. The community needs their creativity, enterprise,

leadership, and expertise. And as volunteers, they entail no financial cost. They

should be drafted into service to replace people who insist on getting paid.

First, take stock of professionals, retired persons, housewives, or youth with time

or special skills to share. Enlist them for the barangay’s programs and projects.

They are invaluable for promoting the arts and crafts, fitness and sports, hobbies

and livelihood courses. They will enliven community life and enhance local pride.

Second, consider the cultural needs of the community: a library or reading

center? literacy or numeracy courses? agro-industrial seminars? Lectures,

demonstrations on technology or survival skills are always useful. Make room for

activities that refine culture and civilization. Why just physical sports or singing

concerts when there can also be chess and scrabble or Sudoku, sewing circles, or

artists’ corners?

Television and its inane fare is bastardizing grassroots culture while making a

mockery of formal education.

7.

Check out the Sangguniang Kabataan and its activities. It shouldn’t be all sports

and pop concerts.

First, draw the attention of the college kids to the fact that ten percent of the

barangay’s income is available for youth development. It’s a lot of money to

manage -- much more than campus fundraisers can hope to earn. This fund

should not be cornered by the young surrogates of older officials (their own

children along with barkada). It shouldn’t be frittered away in activities that do

nothing significant for the youth.

Second, challenge campus youth to use the community as their real-life

workshop for applying their leadership and management skills. Why wait after

college to face real-world challenges? They shouldn’t be content with the

virtual-reality of campus life, using virtual-reality tools, under virtual-reality

situations. The reality in the neighborhoods cry out for attention and

improvement!

Much of the SK’s money is wasted on unproductive activities. It is not treated as

capital for development. Imaginative use of it would attract counterpart funds

from business and other institutions to finance youth-initiated programs. The

school may need a feeding program. The poor may need a student loan program.

Pupils in distant places need shuttle service to and from school, even by

motorela. A youth cooperative may need to be capitalized. These are proper

initiatives for SK to undertake. It shouldn’t be all sports, pop concerts, or LakbayAral junkets!

8.

Crank up the local economy with programs that capitalize on local opportunities

and existing resources.

First, do an inventory of manpower (skilled workers, craftsmen, artisans, artists,

designers, other talents). Then, explore four areas of concern:

a.

Agri-business in rural areas: special crops, contract farming, contract

livestock raising, tree farming, fishponds, and so on.

b.

Tourism: rivers, hills, valleys, coastlines, flora and fauna, and other

environmental features have potential for adventure. In urban areas, there

are budding talents with technology-development potential. There are

opportunities for developing/showcasing talents in the arts and crafts.

c.

Production/Processing enterprises: food processing, handicrafts, weaving,

clay products, furniture or woodworking, garment making, and the like.

d.

Skills Development: metal works, masonry, electrical, carpentry, care-giver

or therapy services, beauticians, and the like.

For these activities, interface with resource agencies and institutes such as

TESDA, the Agricultural Training Institute, and the Cooperatives Development

Authority to assure quality and quantity of performance.

Every GBM chapter should produce a directory of skills, services, and products in

its locality and endorse the same to prospective users and customers

everywhere. Hand-in-hand with government and business, let the GBM Chapter

be a capability-building center for build up the local economy.

This 8-point Agenda is meant to ignite self-reliant, reform-oriented initiatives. It

should push the reform process forward until it takes on a life of its own and

make autonomy, self-government, and the principle of subsidiarity a reality.

(Refer to the Yellow Book or the GBM Guide to Good Barangay Governance for

more details. )

IV.

KEEP ISSUES ALIVE, PEOPLE AWAKE

THE “PULONG-PULONG”

There shall be a regular forum to be announced as a “PULONG-PULONG” in every

chapter. It shall focus on governance and the social, economic, and political

conditions of the locality. (Cf. “Moderator’s Guide”.)

Until the Barangay Assembly learns to convene often or regularly, this Forum shall

be the community’s vehicle for raising issues publicly and addressing them

collectively. It should generate communitarian solutions.

Role of the Barangay Officials

It is not necessary for the officials to be involved but they should be invited.

(Simply explain that this is primarily for people who are not in power.) They

shouldn’t feel threatened or resentful of it; they’re supposed to promote the

democratic process and encourage citizens to participate in it. But do let them

understand that this forum shall continue until or unless the Barangay Assembly

convenes regularly (not just twice a year, which is the minimum required by law)

and in a manner befitting a body of sovereign citizens.

Cautionary Note

The GBM is embarked on a civilizing mission. Its members do not engage in

disruptive acts or illegal moves, nor incite people to violence; it would violate

solidarity. It will create dissension instead of harmony and set back the political

maturity of the community.

By all means, let issues be debated as often or as passionately as people feel, but

at no time should matters escalate beyond words. The object of Pulong-Pulong is

to get people used to public deliberations by letting them reason together,

exchange views, clarify issues, and reach consensus on issues that concern them

or affect their welfare as a community.

Consensus is the hallmark of a community’s political maturity.#

V.

GBM: A PEOPLE’S MOVEMENT

The GISING BARANGAY MOVEMENT is an alliance

of Filipinos who wish to do the little things

in the barangay that together make up

the big things in the nation.

A non-stock, non-profit, and non-partisan corporation registered with the

Securities and Exchange Commission.

Recognized and accredited by the Ombudsman as a corruption-prevention

unit.

The GBM Convenor calls meetings and presides over the chapter, coordinating its

activities, acting as its spokesperson, and signing on its behalf.

He or she is assisted by a Deputy-Convenor who supervises operations and the

work of the committees, as follows:

1.

Membership Committee and Secretariat – headed by a Chairman, assisted

by a vice chairman. It screens and accredits applicants, issues membership

cards, maintains an up-to-date directory, serves as clearinghouse, arranges

for meetings, disseminates materials and notices, keeps custody of property,

and provides other support services.

2.

Education and Field Operations Committee - headed by a Chairman,

assisted by a vice chairman. It develops the regime of learning and doing

activities needed by GBM, conducts Empowerment Seminars, produces

handbooks or training materials, and undertakes outreach operations to

expand the GBM vertically and horizontally.

3.

Ways and Means Committee – headed by a Chairman, assisted by a vice

chairman. It anticipates and works out logistical requirements of GBM

operations, raising funds and other resources therefor.

4.

Socioeconomic Committee – headed by a Chairman, assisted by a vice

chairman. It plans and arranges for technical assistance for self-help

programs and projects that generate economic benefits and livelihood for

the members – in three areas: Agribusiness, Production and Processing, and

Skills Development.

5.

Culture and Sports Committee, headed by a Chairman, assisted by a vice

chairman. It plans and undertakes programs to promote cultural and sports

activities: to draw out and identify local talents, to help develop them, and

to project them through appropriate events such as concerts, exhibitions,

demonstrations, and competitions

6.

Finance Officer, assisted by a Treasurer, charged with handling funds and

disbursements, accounting for same, and reporting thereon.

The GBM Hierarchy

It consists of ascending levels of Convenors: barangay, municipal/city,

provincial, regional, national.

The higher level Convenor handles the task of convening the next lower

level convenors in order to coordinate, plan, deliberate, or decide on

organizational matters and activities, as follows:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

7.

Barangay Convenor presides over the zone/district convenors.

Municipal/City Convenor presides over the Barangay Convenors.

Provincial Convenor presides over the Municpal/City Convenors,

Regional Convenor presides over the Provincial Convenors.

National Convenor presides over the Regional Convenors

Regional Convenors constitute the National Convenors’ Steering

Council which elects the National Convenor and a Deputy National

Convenor.

The Deputy National Convenor shall organize, manage and supervise

national committees.

Operating Policy

Each level operates autonomously, coordinating closely with the level

immediately above or below it. The standard hierarchy or command

structure shall not apply. Decisions are be made collegially-- by

consensus. They are all sovereign citizens! Standing committees at every

level correspond to those enumerated above.

The barangay chapter is the basic organizational unit.

Immediate Objective of the Chapter

The main objective of the GBM Chapter is to engage all sectors of the

barangay in its governing process. Special focus is on recruiting the

usually inattentive citizens: the middle and upper class residents

(professionals and the well-off) who generally ignore the governing

processes of the barangay and who surrender their sovereignty to

traditional politicos, or trapos.

It is their absence and inattention that enable the trapos to manipulate the

less-educated in the neighborhoods and corrupt them on behalf of the Big

Trapos.

Their failure to participate prevents the principle of checks-and- balances

from operating in the barangay government. It deprives the community of

their valuable ideas, insights and experience. In fact their inputs are

absolutely needed in the deliberations of the Barangay Assembly, the

community’s parliament (supreme governing body). It is the only

mechanism for ensuring transparency and accountability at the base of the

Republic.

A Task Force

GBM members are volunteers who can no longer watch idly as unscrupulous

trapos dishonor the Constitution and its enabling laws. The GBM, however,

harbors no illusion about being a permanent organization with a selfperpetuating bureaucracy. It is not meant to duplicate or, worse, to compete

with the duly constituted government and other institutions whose mandates,

while echoing the GBM’s thrusts, do not fulfill its objectives.

Accordingly, GBM merely promotes ideas and facilitates processes that

catalyze constructive citizen involvement in their barangay.

This “task force” approach is premised on the recognition that there are already

far too many institutions, public and private, that are devoted to ideas and

processes the GBM seeks to promote – which are nothing more nor less than

those mandated by our laws.

But the failure of the government to implement them and civil society to

institutionalize them, exacerbated by ignorance and apathy, make it imperative

for the GBM to take the initiative until others are sufficiently awakened to

perform the task themselves without prompting from others. #

Contact Address

Gising Barangay Movement

112 Hayes Street

Cagayan de Oro City 9000

Philippines

or

P.O. Box 0496, Cagayan de Oro City, Philippines

Phone: (08822) 74-5150