Higher Education Overview: North West University

advertisement

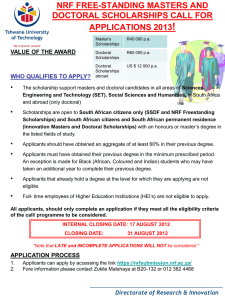

HIGHER EDUCATION OVERVIEW NORTH WEST UNIVERSITY MARCH 2012 Economic Growth and Human Development A substantial body of academic and technical literature provides evidence of the relationship between informationalism, productivity and competitiveness for countries, regions and business firms. But, this relationship only operates under two conditions: organizational change in the form of networking; and enhancement of the quality of human labor, itself dependent on education and quality of life. (Castells and Cloete, 2011) The structural basis for the growing inequality, in spite of high growth rates in many parts of the world, is the growth of a highly dynamic, knowledgeproducing, technologically advanced sector that is connected to other similar sectors in a global network, but it excludes a significant segment of the economy and of the society in its own country. The lack of human development prevents what Manuel Castells calls the ‘virtuous cycle’, which constrains the dynamic economy. (Castells and Cloete, 2011) Connecting growth to human development – trickle down don’t work 2 Gross Domestic Product (GDP) per capita vs Human Development Index (HDI) Country GDP per capita (PPP, $US) 2007 GDP ranking HDI Ranking (2007) GDP ranking per capita minus HDI ranking Botswana 13 604 60 125 -65 Mauritius 11 296 68 81 -13 South Africa 9 757 78 129 -51 Chile 13 880 59 44 +15 Costa Rica 10 842 73 54 +19 Ghana 1 334 153 152 1 Kenya 1 542 149 147 2 802 169 172 -3 Uganda 1 059 163 157 6 Tanzania 1 208 157 151 6 Finland 34 256 23 12 11 South Korea 24 801 35 26 9 U.S.A. 45 592 9 13 -4 Taiwan (China) Mozambique 3 Economic Growth in Post Apartheid SA During the first decade of the post-apartheid era in South Africa, gross domestic product (GDP) grew at a ‘modest rate’, averaging one percent, though edging up more recently to three percent. Nevertheless, this has been the longest period of positive growth in its history How did this growth happen? The envisaged post-1994 economic policies for the development project stated that the economy would require steering onto a new development path which, amongst others, would reduce dependence on resource sectors through industrial deepening and diversification (Bhorat 2010). 4 Economic Growth and the 2008 Financial Crisis The worst impact of the 2008crisis, resulted in at least a million job losses, and is associated with: • structural industrial weaknesses and de-industrialization as a result of development centred around mining and minerals • continued reliance on extractive mining and minerals exports • consumption led growth and increased investment in services sectors, such as finance and retail • speculative asset bubbles in real estate and finance and increased construction (mainly around the 2010 Soccer World Cup) and car sales • the role of the financial sector which has emulated the behaviour of US financial institutions in increasing leverage and misallocation of capital in SA economy. (Mohamed 2009) 5 Poverty Reduction in Post Apartheid SA The stated goal of the post-apartheid economic policy was to reduce poverty, inequality and unemployment. A 2% growth should lead to a 1-7% reduction in poverty, depending on the country – meaning the success of redistributive policies (Bhorat 2010a). In South Africa, poverty declined from 52% in 1995 to 49% in 2005 and in the lower poverty group a 7% decline (31% to 24%). In addition, there were definite gains in poverty reduction, particularly in African female-headed households (Bhorat 2010a). All people, regardless of race, experienced increases in expenditure, meaning that growth was ‘pro-poor’. Despite the modest gains in poverty reduction, the inequality gap did not decrease; instead, it increased amongst all groups. This led Bhorat (2010a) to conclude that in 1994 South Africa was ‘one of the world’s most unequal societies, but by 2005 it may have become the world’s most unequal’. 6 Poverty Reduction in Post Apartheid SA While spending on education and health remained fairly constant in real terms, recipients of social grants (excluding administration) now consumes 3.2% of GDP, up from 1.9% in 2000/01. The total number of beneficiaries increased from 3 million in 1997 to 15 million in 2010 (Woolard and Leibrandt 2011). The share of households in the first income decile with access to grant income increased from 43% in 1995 to almost 65% in 2005 and that even for households in the sixth decile grant income increased from 19% in 1994 to 50% in 2005. According to Bhorat (2010a) this suggests that grant income does not only support the very poor, but also a large number of households in the middle income distribution. More recent estimates suggest that 25% of the population are on social grants and 40 per cent of household income in the poorest quintile (Woolard and Leibbrandt 2011). Post-1994 South African democratic redistribution model operates through extensive social grants at the bottom end, few benefits at the middle of the distribution curve and the main growth is at the de-racialising top end. Based on this growth path, both Bhorat (unequal income distribution) and Mbeki (the disempowerment of welfarism) express concern for the future of democracy. 7 Higher Education and Development • SA has a development crisis • Connecting Growth to Human Development • Castells project of Finland, Chile, Taiwan, Costa Rica, SA and California • Two aspects of Higher Education that I want to concentrate on are Knowledge production (growth) and participation (skills and equity) 8 The relationship between scientific excellence and economic development GDP per capita (current US$) Predicted GDP per capita (current US$) United States Economic development Australia Japan UK High Germany Italy Korea Mexico Brazil Low Argentina South Africa Tunisia China Egypt India Low High Influence of Scientific Research (R = 0.714, P = 0.218) (R = 0.961, P = 0.002)* Data source: Thomson Reuters InCitesTM (21 September 2010); The World Bank Group (2010) 9 Vuyani Lingela, 24 November 2011 Knowledge Production: SA International Performance According to the NPC: 1. SA produces 28 PhD graduates per million of the population while UK =288; US = 201; Australia=264; Korea=187; Brazil = 48 2. World Bank: SA has tripled R&D investment since 1994, but the total number of FTE researchers increased by only 33%. SA has approximately 1.5 FTE researchers per 1000 employed; countries with similar ratio of R&D to GDP expenditure like Portugal = 4.8 and Italy = 3.6 3. NPC goals: Increase PhD graduates from 1420 to 5000 p.a and increase percentage of staff with PhD’s from 34% to 75% 10 Participation Rate and Development Indicators Gross tertiary education enrolment rate Quality of education system ranking Overall global competitive ranking (2008) (2009-2010) (2010-2011) Ghana 6 71 114 Kenya 4 32 106 2 81 131 Tanzania 2 99 113 Uganda 4 72 118 20 48 76 26 50 55 17 (8.5) 130 54 94 6 7 98 57 22 82 26 4 Country Stage of development (2009-2010) Mozambique Botswana Mauritius South Africa Stage 1: Factor-driven Transition from 1 to 2 Stage 2: Efficiency-driven Finland South Korea United States Stage 3: Innovation-driven 11 BRICS: Selected higher education and economic development indicators (WEF 2010) Country Stage of development (2009-2010) GDP per capita (USD) (2009) Tertiary education enrolment rate (2008) Global Competitiveness Index ranking (2010–2011) Brazil Stage 2: Efficiency-driven 8 220 35 58 Russia Stage 2: Efficiency-driven 8 694 77 63 India Stage 1: Factor-driven 1 031 14 (2007) 51 China Stage 2: Efficiency-driven 3 678 23 27 South Africa Stage 2: Efficiency-driven 5 824 17 54 12 Gross participation rates in SA higher education by Race, 1986 - 2009 70% 60% % Participation Rate 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% 1986 1995 2000 2005 2009 African 5% 9% 10% 12% 13% Coloured 9% 10% 9% 13% 15% Indian 32% 35% 40% 51% 45% White 61% 61% 57% 60% 58% Average 11% 14% 14% 16% 17% 13 Effective Participation: Throughput rates of general academic first-B-degrees Graduated in regular time (3 years) - general academic first Bdegrees, excluding Unisa Black White 52% All 43% 43% 35% 33% 29% 24% 28% 24% 21% 11% 11% 13% 14% Source: Fisher and Scott, 2011 13% Knowledge Economy Central role of knowledge in government policies Focus in Knowledge Policies on: 1. Global economic competitiveness 2. Innovative capacity of societies 3. High Level Skills and Competencies of Labour force (Knowledge workers) Core issue: Most effective investment of public funds Claus Swabe (WEF) Not Capitalis, but Talentism International Knowledge Policies – Maassen Starting point = New conditions in the global economy Growing focus of national (regional – supranational) policy makers and other central socio-economic actors on the university as a driver for economic growth through its role as source for innovation and job creation. Consequence = Two new university governance aspects First targeted policies for and investments in universities’ research capacity are assumed to be needed in order to improve the global competitiveness of a specific economy. Second, targeted policies for and investments in connecting the enhanced research capacity of universities to the knowledge needs of society (incl. private and public sector companies and organisations) in order to ensure the link of new knowledge to economic growth (innovation & new jobs ). «Balancing academic excellence with economic relevance» HERANA: 8 African Countries and Flagship Universities Higher Education Research and Advocacy Network in Africa • Starting point is to increase understanding of the complex links/interactions between higher education and economic development – at national and institutional levels • Three successful systems – Finland, South Korea and North Carolina (USA) • Eight African countries and their national universities: Botswana, Ghana, Kenya, Mauritius, Mozambique, South Africa (Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University/UCT), Tanzania, Uganda • Network consists of 50 people from 15 countries, include Manuel Castells, Peter Maassen (Oslo) John Douglas (Berkeley) and Pundy Pillay (Wits) Funded by: Ford, Carnegie, Rockefeller, Kresge and Norad Findings from Three Successful Systems Finland, South Korea, North Carolina (USA) • As part of reorganising their ‘mode of production’, a pact was reached about a knowledge economy (high skills and innovation) as development driver • Close links between economic and education planning • High participation rates with differentiation • Strong ‘state’ steering (projects) • Higher education linked to regional development • Responsive to the labour market • Strong coordination (prime ministers office) and networks Pundy Pillay (2010) Linking higher education to economic development: Implications for Africa from three successful systems (CHET) HERANA Findings on 8 African Countries and Flagship Universities 1. There is a lack of agreement (pact) between national and university stakeholders about a development model, and about the role of higher education in development 2. Only one of the eight countries (Mauritius) has accepted knowledge, and the associated human capital and research development, as a key driver for economic growth 3. Linking higher education to development requires considerable coordination within government, and between government, the university and external funders, and all three must contribute 4. The absence of a pact about the role of the university in development affects negatively implementation and resource allocation – which raises the possibility that we a have double problem; lack of capacity and a lack of agreement 19 Dis-coordinated Knowledge Policies 1. Department of Higher Education and Training a) Shocked by Chet’s finding of 3 million NEET’s and have become ‘overwhelmed’ with FET and training b) In Ministers budget speech referred to research on page 12 of 13 and never used knowledge economy and Africa, not to mention the globe (a local communist) 2. Department of Science and Technology b) Opening line knowledge economy and global competitive c) Presses all the knowledge production buttons d) Never spoke beyond pleasantries to DHET advisor 3. Two Departments focus on different and over-lapping aspects of the system, without any co-ordination 20 National Planning Commission (Nov 2011): Functions of HE (1) Higher education is the major driver of the information-knowledge system, linking it with economic development...Universities are key to developing a nation. They play three main functions in society: Firstly, they educate and train people with high-level skills for the employment needs of the public and private sectors. Secondly, universities are the dominant producers of new knowledge, and they critique information and find new local and global applications for existing knowledge. Universities also set norms and standards, determine the curriculum, languages and knowledge, ethics and philosophy underpinning a nation's knowledge-capital. South Africa needs knowledge that equips people for a society in constant social change 21 NPC: Functions (2) "Thirdly, given the country's apartheid history, higher education provides opportunities for social mobility and simultaneously strengthens equity, social justice and democracy. In today's knowledge society, higher education underpinned by a strong science and technology innovation system is increasingly important in opening up people's opportunities." (p262) For the first time knowledge production and equity are linked by stating that "high quality knowledge production cannot be fully realized with a low student participation rate" (p274). 22 Also universities are not mainly fro individual mobility or for equity redress - equity is mentioned last and transformation in the Castells sense NPC: Knowledge Enthusiasm The NPC is so enthusiastic about knowledge that it declares that "knowledge production is the rationale of higher education" (p271) - indeed a radical departure from the traditional 'rationale' of higher education in Africa, that is, disseminating (teaching) knowledge from somewhere else. Posters outside Parliament for Thursday’s State of the Nation: Knowledge Economy and Development Opportunities. At ANC 100th Zuma said: “Education and skills are the key priority for our people” These are huge steps away from HE as individual mobility and an equity instrument – but in State of Nation announced the biggest infrastructure project in history – not a word of KE 23 NPC Knowledge Policies 1. the notion of knowledge production consists of a combination of PhD education and research output. 2. a target of tripling the number of doctoral gradates from 1,420 to 5,000 per annum, and increasing the proportion of academic staff with PhDs from 34% to 75% 3. a number of world-class centres and programmes should be developed within the national system of innovation and the higher education sector. 4. a new future scholars programme needs to be developed, both to increase the proportion of staff with PhDs and to meet the increasing demand for professional PhDs in the non-university research, financial and services sectors 5. role of science councils should be reviewed in light of the worldwide tendency to align, or merge, research councils with universitie 24 NPC: Differentiation 1. deals with the worldwide policy debate about the concentration of resources by proposing world-class centers and programmes across institutions (High science - Ska) 2. advises the Ministerial Committee for the Review of the Funding of Universities that such revisions should be based on the needs of a differentiated system with adequate provision for both teaching and research 3. requires flexible pathways for student mobility between institutions 4. the Higher Education Quality Committee should finally start developing a core set of quality indicators for the whole system; 25 DHET Green Paper Research and innovation 1. Economic depends on innovation and technology absorption 2. While investment in research has tripled, there has not been a commensurate increase in personnel 3. Total knowledge output has increased 64% (2000-2009) but the system must become more productive 4. Poverty is a significant constraint on masters and Phd studies – students under pressure to obtain jobs?? 5. Drastically increase number and quality of masters and PhD’s 6. Need for increased coordination between DHET and DST 7. Caliber and workload of academic staff must be addressed 8. Long term plan for renewing the academic profession doctorates for academics and professions 26 NPC and DHET: The Good, the Bad and the Incomprehensible 27 1. Differentiation (whatever form) is official 2. Knowledge production (PhD and research output must increase – different counts of research outputs) – at last recognising the knowledge producing role of the university 3. Big focus on doctorate – for academics (target more than 60%), professions research councils and other sectors (finance) 4. Good quality undergraduate education – including infrastructure funds for labs, libraries, housing 5. Improvement of through put – efficiency 6. Dramatic increase in participation rate – mainly in FET 7. Mission and profile differentiation 8. Creation of a connected system 9. Improved Coordination between DSHT and DHET (HESA meeting) 10. More funding for higher education Ten Year Innovation Plan The Government of South Africa is implementing the Ten Year Innovation Plan which includes five “Grand Challenges” that build on and expand the country’s research capabilities (Minister Naledi Pandor, 2009). • The first grand challenge is to tap the potential of the bio-economy for the pharmaceutical industry. • The second grand challenge is to build on investments in space science and technology. • The third grand challenge is to move towards the use of renewable energy. • The fourth grand challenge is to play a leading, regional role in climate change. • The fifth and final grand challenge is termed “human and social dynamics”. 28 Vuyani Lingela, 24 November 2011 The rise of doctorates 45.0% 40.0% 40.0% Major expansion of higher education has boosted PhD output in many countries, shown here as average annual growth of doctoral degrees across all disciplines. 1998 - 2006 35.0% 30.0% 25.0% 20.0% 17.1% 15.0% 10.0% 10.0% 8.5% 7.1% 6.4% 6.2% 6.2% 6.1% 5.2% 5.0% 2.5% 1.0% 0.0% 0.0% -2.2% -5.0% China Mexico Denmark India Korea South Africa Japan Australia Poland Source: Nature. International weekly journal in Science United Kingdom United States Canada Germany Hungary HERANA - Total PhD enrolled and total PhD graduates, 2001 - 2007 7,000 6,080 6,000 5,000 4,000 3,000 2,000 1,759 1,103 1,000 931 187 299 34 126 0 Botswana Makerere 6 0 Eduardo Mondlane 854 674 648 83 Ghana 47 *Mauritius 163 90 Nairobi Dar es Salaam 203 NMMU University of Cape Town * Mauritius enroll large numbers of students as MPhil students, and depending on their performance only some graduate as PhD students KP outputs: Universities of Sao Paolo, Pretoria and Cape Town 10000 9109 9000 8206 8000 7000 6000 5000 4000 3000 2244 2000 1187 1000 196 1184 1390 178 0 USP 2010 UP 2009 Doctoral graduates UCT 2009 SA totals 2009 Research publications 31 Summary 1. Unprecedented shift from HE as instrument to advance equity and individual mobility to HE as crucial part of development 2. Policy recognition of importance of coordination of policy and implementation, but little sign of positive cooperation yet 3. SA a Medium knowledge producing system, rated around 30th in the world 4. SA has a few global high visibility big science projects 5. SA seems to be doing better in research output than in producing doctorates 6. Over –enthusiasm about dramatic increase in doctoral production 7. Next session on the Doctoral Project will explore this ‘doctoral exuberance’ through different empirical prisms (Alan Greenspan initially attributed the 2008 crash to ‘irrational market exuberance’). 32 Graph 1 sets out data on key elements of SA’s high-level knowledge production for the period 1996-2010 expressed as doctoral enrolments, doctoral graduates and research publication units. Average annual changes in these totals are reflected in Graph 2. 14000 11468 12000 9 800 1 0000 8790 4 000 2 000 Research pubs 7763 8 000 6 000 PhD enrolments 9939 5 622 5528 9 748 6 394 8 003 6483 6660 8 353 5 164 5456 5 936 6 85 761 961 9 69 1 104 1100 1 182 1 421 1996 1998 2000 2 002 2004 2006 2 008 2010 PhD graduates 0 Doctoral enrolments Doctoral graduates R esearch publications 33 Graph 2 divides Graph 1 growth rates into the period between (a) 1996 and 2002, which covered the period of the 1997 HE White Paper and the 2001 National Plans, and (b) 2004-2010 which covered the introduction and implementation of the new 2003 government funding framework. 8.0% 7.0% 6.0% 7.0% 6.6% 6 .0% 5.9% 5 .4% 5.0% 4.5% 4 .3% 4.0% 4.0% 3.0% 2.4% 2.0% 1 .0% 0 .0% 1996-2002 Doctoral enrolments 2004-2010 Doctoral graduates 1996-2010 R esearch publications 34 Graph 3 divides the doctoral enrolment totals for 1996-2010 into race groupings. The main change has been in African doctoral enrolments, which increased from 663 in 1996 to 5066 in 2010, when African doctoral enrolments exceeded that of White enrolments for the first time. 6000 4861 5 000 4486 4 020 4000 3 875 4819 3993 3583 5066 African White 4 853 4 568 4 022 2 933 3 000 2239 2000 1610 1 053 1000 0 683 197 264 1996 344 256 1998 African 464 3 27 2000 7 68 8 13 774 8 68 419 5 29 585 575 6 81 2 002 2004 2006 2 008 2010 6 19 Coloured Indian White Indian Coloured 35 Graph 4 shows how the % of doctoral enrolments by race group changed between 1996 to 2010. African doctoral students rose from 13% in 1996 to 33% in 2004, and 44% in 2010. 9 0% 8 0% 78% 7 0% 62% 55% 6 0% 49% 5 0% 41% 4 0% 33% 13% 13% 12% 10% 2004 2 008 1 0% 0% 42% African White 25% 3 0% 2 0% 44% 14% Coloured+Indian 9% 1996 2 000 African White Coloured +Indian 2010 36 Graph 5 offers a first picture of the doctoral output efficiency of SA’s public HE system, based on output ratios which appear in the 2001 National Plan. The National Plan set this as an output norm: • • The ratio between doctoral graduates in a given year and doctoral enrolments should = 20%. So, if 10 000 doctoral students were enrolled in the HE system in year X, then at least 200 of these students should graduate in year X. This norm was based on a further target norm that at least 75% of any cohort of students entering doctoral studies for the first time in (say) year Y, should eventually graduate. Calculations had shown that if the cohort output norm was to be achieved, then the 20% ratio of total graduates to total enrolments would have to be met over a period of time. 37 Graph 5 shows that, as far as doctoral outputs are concerned, the Public HE system has failed to meet the National Plan’s efficiency targets. Calculations show that over the period 1996–2002, less than 50% of students entering doctoral programmes in SA will eventually graduate. 8 0% 75% 7 0% 6 0% 52% 5 0% 45% 45% 4 0% 3 0% 2 0% 20% 14% 12% 12% 1998-2002 2 002-2006 2006-2008 1 0% 0% R atio of graduates to enrolments Cohort graduation equivalent National target 38 Graph 6 offers estimates of the effects of inefficiencies in SA’s doctoral programmes. For example, over the period 2005-2010, SA should, on the National Plan’s norms, have produced a total of 12 285 doctoral graduates but in fact produced only 7 711, leaving a “shortfall” of 4 739 graduates (who would have been drop outs from the system). 2005 - 2010 -4 739 Shortfall -2735 2000 - 2004 2005 - 2010 National Plan target 2000 - 2004 2005 - 2010 Actual graduates produced -6000 -4000 -2000 2000 - 2004 0 2000 4000 T otal 2005-2010 12285 7 711 7 546 4976 6000 8000 T otal 2000-2004 10000 12000 14000 39 Doctoral degree cohorts (2001, 2002, 2003): Average dropout & graduation by Race New entrants Race 2117 African Academic year Registered at beginning of year 274 555 281 26 655 860 860 41% Dropped out (Cumulative) 606 1017 1257 1257 59% Registered at beginning of year 274 119 44 4 91 130 130 47% Dropped out (Cumulative) 45 108 144 144 53% Registered at beginning of year 555 193 101 4 202 254 254 46% Dropped out (Cumulative) 116 216 301 301 54% Registered at beginning of year 3040 1034 441 58 1213 1523 1523 50% Dropped out (Cumulative) 538 1158 1517 1517 50% Registered at beginning of year 5986 2011 867 92 2161 2767 2767 46% 1305 2499 3219 3219 54% Graduated (Cumulative) White 3040 Graduated (Cumulative) Total 5986 Graduated (Cumulative) Dropped out (Cumulative) • *Year 7 665 Graduated (Cumulative) Indian Year 5 2117 Graduated (Cumulative) Coloured Year 1 Total graduates & dropouts for cohort The End of year 7 dropping out numbers also include students that may have registered in future years to complete their studies. Source: DHET. 2011, CHET PhD analysis Doctoral degree cohorts (2001, 2002, 2003): Average dropout & graduation by University Group New entrants Academic year Year 1 Year 5 Total graduates & dropouts for cohort *Year 7 High Productive Universities : University of Cape Town, University of Pretoria, Rhodes University, University of Stellenbosch, University of the Witwatersrand 3098 Registered at beginning of year Graduated (Cumulative) 3098 1230 509 29 1179 1532 1532 49% 495 1130 1566 1566 51% Dropped out (Cumulative) Other Universities : University of Fort Hare, University of the Free State, University of Limpopo, North-West University, University of the Western Cape 978 Registered at beginning of year Graduated (Cumulative) 978 10 316 372 144 485 485 50% 210 388 493 493 50% Dropped out (Cumulative) Comprehensive Universities : University of Johannesburg, Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University, University of South-Africa, University of Venda, Walter Sisulu University, University of Zululand 1702 Registered at beginning of year Graduated (Cumulative) 1702 407 187 50 554 672 672 39% 530 869 1030 1030 61% Dropped out (Cumulative) Universities of Technology : Cape Peninsula University of Technology, Central University of Technology, Durban University of Technology, Mangosuthu University of Technology, Tshwane University of Technology, Vaal University of Technology 208 Registered at beginning of year Graduated (Cumulative) Dropped out (Cumulative) 208 3 58 56 27 78 78 38% 70 112 130 130 63% 5986 2011 867 92 2161 2767 2767 46% 1305 2499 3219 3219 54% Total 5986 Registered at beginning of year Graduated (Cumulative) Dropped out (Cumulative) Source: DHET. 2011, CHET PhD analysis Enrolments South African Universities – PhD graduates by nationality South African International 100% 80% 29% 30% 34% 34% 71% 70% 66% 66% 60% 40% South African International 2007 7 195 2 853 2008 6 959 3 035 2009 7 213 3 316 2010 7 841 3 749 Graduates South African International 2007 900 374 2008 829 353 2009 908 470 2010 931 489 South African PhD students graduation rate by 20% 15% nationality South African International 14% 2007 2008 2009 2010 Norwegian Universities - PhD graduates by nationality Norwegian International Graduation Rate 0% 13% 13% 23% 25% 26% 28% 33% 77% 75% 74% 72% 67% 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 20% 0% 12% 13% 13% 12% 11% 2007 60% 40% 13% 12% 100% 80% Total 10 048 9 994 10 529 11 590 Total 1 274 1 182 1 378 1 420 2008 2009 2010 It is important to note that the two countries produce almost the same number of PhD graduates but that South Africa’s population is in the order of 48 million whilst Norway’s population is 4.8 million Graduates 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 Norwegian 789 937 851 858 889 International 241 308 297 326 438 Total 1030 1245 1148 1184 1327 Academic staff with doctoral degrees are a key input for high-level knowledge production is. Permanent academic staff in this category should be the major producers of research outputs, and at an input level the main supervisors of doctoral students. Graph 7 shows how the totals of permanent academic staff with doctoral degrees changed between 1996 and 2010. 18000 16000 1 4000 1 3449 13098 4647 4658 14184 14673 15423 1 5809 15936 5 146 5403 1 6684 T otal permanent 12000 10000 8 000 6 000 4561 4572 4485 5957 Highest qualification PhD 4 000 2 000 0 1 996 1998 2000 2002 Doctorate as highest qualification 2004 2 006 2008 Total permanent 2010 43 Graph 8 divides public HE institutions into the 3 categories used for national planning purposes, and sub-divides the 11 universities into a group of 6 which produces 60% of the HE system’s total high-level knowledge products and the remaining 5. The groups are: High productive universities UCT, UKZN, Pretoria, Rhodes, Stellenbosch, Wits Other universities Fort Hare, Free State, Limpopo, North West, UWC Comprehensive universities UJ, NMMU, Unisa, Venda, WSU, Zululand Universities of technology Cape Peninsula, Central, Durban, Mangosuthu, Tshwane, Vaal DUT 44 Graph 8 60% 50% 40% 45% 36% 48% 41% 29% 2 0% 5% Other 35% 38% 28% 29% High productive 44% 40% 36% 30% 10% 44% 27% 7% 8% 2002 2 004 28% 10% 29% 40% Comprehensive 28% 13% 15% 2008 2010 UoT 0% 2000 High productive universities Other universities 2 006 Comprehenives Universities of technology 45 The low proportions permanent academic staff with doctoral degrees must have an impact on the numbers of doctoral students which can be enrolled and supervised. Graph 9 shows what the ratios have been between doctoral enrolments and permanent academic staff with doctorates. A ratio of two doctoral enrolments per permanent academic with a doctorate could be used as an indicator of institutional capacity. Graph 9 shows that the high productive group of universities and the comprehensives had ratios above 2 in 2010, which could be taken to imply that they have reached capacity as far as doctoral enrolments are concerned. Increases in their doctoral enrolments should depend on more academic staff obtain their own doctoral degrees. The 2:1 norm suggests that the other group of 5 universities and the universities of technology may have spare supervisory capacity, but their ability to deal with this depends on their current financial and efficiency levels. 46 Graph 9 2 .5 2 .2 2 .0 1 .7 2 .1 1 .8 1 .5 2.1 1.7 1.7 2.1 2.1 Other 1.7 1 .2 1.0 0.5 1.1 1 .2 High productive Comprehensive UoT 1.1 1.2 0 .8 0.0 2 000 High productive universities 2 004 Other universities 2 008 Comprehenives 2 010 Universities of technology 47 Government’s funding incentives for research outputs are complex because of the 2-year time lag between the completing of an output and the receipt of a funding allocation, and the weightings applied to research outputs. Graph 10 shows what research funding totals were generated by each output category. Graph 11 shows what the Rand values can be assigned to research output units. 48 Graph 10 R 'millions 2500 2225 2000 Total 1837 1540 1500 1000 500 845 474 192 0 1245 1237 179 2004/05 919 489 228 202 2005/06 Publications units 1225 505 265 Pub. units 1 048 1024 652 596 310 343 253 298 282 2006/07 2007/08 2008/09 Research masters grads 796 379 4 14 365 375 2009/10 2010/11 Doctoral graduates 539 461 PhD graduates Research M grads 2011/12 Total 49 Graph 11 R'000 450 393 400 Per PhD graduate 3 50 2 86 3 00 251 250 200 191 150 1 00 50 87 66 91 82 110 1 02 1 10 134 Per publication unit Per research M grads 0 2005/06 Per publication unit 2007/08 2009/10 Per research masters graduate 2 011/12 Per doctoral graduate 50 It could be argued that the high Rand values for doctoral graduates should have functioned as strong incentives to institutions to expand these outputs. The data in Graph 12 suggest these financial incentives have not yet affected doctoral graduate growth, which was 3.5% pa between 2000 & 2004, and 3.6% pa between 2005 and 2010. There are likely to be a number of reasons why doctoral graduate totals have not yet responded to the output funding incentives introduced for the first time in the 2004/5 financial year. One explanation is that only a few universities have been able to benefit from the introduction of government research output incentives. A second explanation is that doctoral processes in SA have been characterised by high levels of inefficiency, as has been seen in Graphs 5 and 6. 51 Graph 12 6.7% 7.0% 6 .2% 5.8% 6.0% 5.0% 4.4% 4.4% 4 .0% 3.5% 3.6% 3 .0% 2.0% 1.5% 1.0% 0.0% Publication units Masters graduates: Research masters coursework + research graduates 2 000-2004 Doctoral graduates 2 005-2010 52 Graph 13 shows that government output funding can be related to staff capacity. In 2011/12 the high productive university group generated R290 000 in government research funds per permanent academic, which was considerably higher than the averages for the other groupings. R'000 350 290 3 00 High productive 250 2 15 192 200 1 50 135 58 0 Other 94 100 50 130 39 68 46 60 66 Comprehensive 8 13 19 25 2 005/06 2 007/08 2 009/10 2 011/12 High productive universities Other universities Comprehenives UoT Universities of technology 53 Graph 14 relates doctoral graduate funding to permanent academic staff, but also compares this doctoral funding to research publication funding per permanent academic. The graph shows that in 2011/12 the high productive universities group generated R82 000 in doctoral funding per permanent academic, and R126 000 in research publications. The amounts are lower, but similar wide differences can be seen in the other institutional categories. These lower amounts generated by doctoral graduates could be related to institutional inefficiencies, but also to institutional incentives. Some institutions distribute publication output funds to authors, but few (if any) distribute doctoral graduate funds to supervisors. Academic staff members are therefore likely to gain more direct personal benefits from research publications than from doctoral graduates. 54 Graph 14 R'000 1 40 126 1 20 1 00 82 80 61 60 42 40 40 20 5 5 11 0 High productive Other universities Comprehenives Universities of technology universities Doctorates Publications 55 Modes of coordination – (Braun 2008; Herana 2011) 1. Coordination of knowledge policies needs to take place at the level of both policy formulation and policy implementation (Braun) 2. Negative coordination is a non-cooperative game that leads … to the mutual adjustment of actors, but not to concerted action nor to cohesiveness of policies 3. Positive coordination goes beyond mutual adjustment… policy integration’ (the coordination of goals) and ‘strategic coordination’ 4. Positive coordination require a Pact, does not absolutely need a whole-government perspective, but a perspective that is agreed upon by a number of relevant political actors. 5. Methods: Departmental Mergers, Coordination Structures, Networks and Visions 56 Defining the ‘pact’ A ‘pact’ is a fairly long-term cultural commitment to and from the University, as an institution with its own foundational rules of appropriate practices, causal and normative beliefs, and resources, yet validated by the political and social system in which the University is embedded. A pact, then, is different from a contract based on continuous strategic calculation of expected value by public authorities, organised external groups, university employees, and students – all regularly monitoring and assessing the University on the basis of its usefulness for their self-interest, and acting accordingly. Knowledge and development > The key findings of the three OECD systems were that knowledge was regarded as a key driver for development, and that education in general, but higher education in particular, is important > Is there agreement about the importance of knowledge for development? > Is there agreement about the role of the university in development? > We looked at national development plans, policies in different departments such as education, science and technology, planning commissions and interviewed some senior officials > At the institutions we looked at the strategic plan and interviewed a selection of leadership and academics Findings: The pact > There is a lack of agreement (pact) about a development model and the role of higher education in development – at both national and institutional levels > There is an increasing awareness, particularly at government level, of the importance of universities in the knowledge economy > The lack of a pact means that what is often explained as a capacity problem could also be because of a lack of agreement > This is a major cause of ‘policy instability’, of a lack of coordination of policies across departments and of implementation, and affects long-term planning and institutional stability SLIDE 1: HIGH LEVEL KNOWLEDGE INPUTS AND OUTPUTS Slide 1 uses averages for 2008-2010 for 4 input and 4 output variables, which reflect the state of high level knowledge production in the HE system, as a way of clustering HE institutions. These indicator averages are summarised in the Slide 1 data table. • Inputs Masters enrolments as % of total head count enrolments Doctors enrolments as % of total head count enrolments % of permanent academic staff with doctoral degrees Ratio of doctoral enrolments to permanent academic staff • Outputs Ratio of masters graduates to masters enrolments (throughput proxy) Ratio of doctoral graduates to doctoral enrolments (throughput proxy) Ratio of doctoral graduates to permanent academics (measure of academic staff research output efficiency) Ratio of research publications to permanent academics (further measure of academic staff research output efficiency) 60 61 Knowledge Production Input and Output Indicators (standardised): 2010 SLIDE 1 Averages (2008 – 2010) 2.00 Cluster 1 1.50 1.00 0.50 Cluster 2 0.00 -0.50 Cluster 3 -1.00 -1.50 Masters enrol Doctors enrol % % Cluster 1: 1. University of Cape Town 2. Rhodes University 3. University of Stellenbosch 4. University of the Witwatersrand Staff PhD Ratio Phd M Grad Rate PhD Grad Rate Ratio PhD enrol to staff grads to staff Cluster 2: 1. University of Fort Hare 2. University of the Free State 3. University of Johannesburg 4. University of KwaZulu-Natal 5. Nelson Mandela Metropolitan University 6. North-West University 7. University of Pretoria 8. University of the Western Cape 9. University of Zululand Pub Outpu Cluster 3: 1. Cape Peninsula University of Technology 2. Central University of Technology 3. Durban University of Technology 4. University of Limpopo 5. University of South Africa 6. Tshwane University of Technology 7. University of Venda 8. Vaal University of Technology 9. Walter Sisulu University 62