Leadership for Social Justice - Education and Leadership in

Anthony H. Normore, Ph.D.

California State University Dominguez Hills

Los Angeles, CA

To create space for honest, authentic conversation about leadership and social justice and how this looks in practice by engaging in discourse about:

◦ the ability to contribute to the well-being of others whose circumstances bar them from completing successful attainment of well-being for themselves

◦ translating society’s beliefs and values to upcoming generations

◦ how global cultural difference fits into the notion of social justice

◦ who we are in relation to those we teach

◦ responding constructively to doubts, disagreements, and defensiveness we might feel

◦ how personal bias impedes student learning

◦ identifying traditional expectations of schools as they relate to cultures of students represented;

◦ anti-racist, anti-bias curriculum where instructional materials acknowledge and honor the integrity of student backgrounds.

Connecting Social Justice, Intercultural Leadership, and Values

Inclusive Leadership and Global Thinking

Pushing the Envelope

Unconscientious Bias

Creating Responsive Instruction

Key Players in the Social Justice Conversation

Social Justice in Schools

Implications for Leadership

Small Group Discussions (11 groups)

Three Scenarios

Wrap-up

Culture of make believe (Jensen, 2004)

◦

Too often we stare without flinching at the baleful design of our culture, which encourages us to honor those who wreak the most havoc on the world (and on human lives) and to scorn those who protest against the havoc and hegemony as opponents of decency and good order

Window on humanity (Kottack, 2004)

◦

Many things are promised, but are said to take time and patience in order for them to happen.

◦

One good way to keep the people away from oppression would be by telling people that they will eventually gain power in the near future.

◦

Grassroots leaders and the larger community can share in a leadership that helps rectify and transform the hegemonic behaviors, practices and beliefs that threaten liberation and learning of ALL children .

Leadership and intercultural dynamics (Collard & Normore,

2009)

◦

Leadership dominated by Anglo-American perspectives

◦

Oblivious to cultural diversity in contemporary world

Global education and inclusive education: Worlds apart?

(Landorf & Nevin, 2007)

Global education and inclusive education can inform one another in their mutual goal to teach respect for the “other,”

The heart of inclusive global education embodies constant questioning and reflection on the meaning of social justice

◦

Is social justice about leveling the playing field or giving the same rights to everyone?

◦ Are there cases where one person’s demand for social justice takes away another?

◦

Where do issues of global cultural difference fit into the notion of social justice?

A primary aim of inclusive education and global education is to facilitate the teaching and learning of respect for oneself and the other

◦

Seems reasonable to hope that by working together, a bridge can be built to a place where recognition for the community is based on respect of each individual who resides within it (Landorf & Nevin,

2007).

Allow ourselves to be pushed

Let’s ask real questions about what we value and believe

Do our beliefs align with our words and actions?

Might it be unsettling?

Do we need to be comfortable when we encounter something sensitive, new or challenging?

Education is a civil right

Are programs designed for students or vice-versa?

Let’s not pretend we do not have biases

An emotional minefield of deep rooted sometimes unconscious biases

Bring forward issues of oppression and address them specifically in nonjudgmental ways

It’s not about blame and shame

It’s about being aware of how institutions operate and who is benefiting.

Create space for honest, authentic conversation (we come from different backgrounds, different language experiences, and different ways of being)

It matters who we are in relation to those we teach

Economically poor, Immigrants, A traditional minority, English language learners,

Students with special needs, or some combination of these

Professional learning for understanding students and their needs

◦

Understand general issues of race, class, culture, privilege – cultural competency

◦

Explore personal bias, how it impedes student learning

◦

Identify norms, family patterns, traditional expectations of schools as they relate to cultures of students represented

◦

Develop communication and engagement skills – culture competency

◦

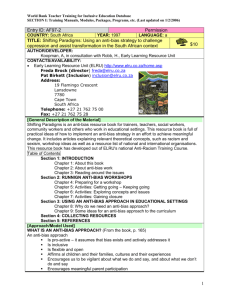

Design anti-racist, anti-bias curriculum

◦

Instructional materials that acknowledge and honor the integrity of student backgrounds

Changing the culture first

Creating responsive instruction

“If I hadn’t been in a fight, I would have become a statistic” – role of student support services

Engaging students in the mission – primary stakeholders must take ownership for their learning

Students need to be aware of our intent and have a voice in evaluating our efforts

Honoring voices of all students and empowering them to “speak their truths”

Agendas for achieving social justice in classrooms are defined and pursued by adults

Why are students missing from this process?

Meaningful relationships, respect, and an equal opportunity for students to take responsibility for their learning and their lives

Listening to students should not be about indulging or exploiting them

Responding constructively to doubts, disagreements, and defensiveness we might feel

Let’s not blame the children who fail – no harm to any child

We fail our students and look for ways to manage the fallout

A change in attitude

Let’s develop the skill and will necessary for success

Let’s engender shared responsibility for all students’ success

Let’s recommit to learning and doing whatever it takes to help all students achieve

To achieve real success for all, social justice must be the goal for any school

Let’s commit to involving the families and the communities

A recommitment to social justice must mean that an injustice has occurred – a violation of Civil Rights

Social justice is difficult to understand

Too many people want to equate it with cultural diversity training or equal opportunity

– and it is so much more.

Source: Witnessing cultural traditions (2010). Journal of the National Staff

Development Council, 31 (4), 4- 72.

Leaders =cultural diversity = need sophisticated understandings =interculturism, global inclusiveness, and social justice.

A leader’s ability to work with diversity = familiarity with cultural maps of ethnic, national and international groups.

A leader has a duty to mediate between groups, to help them discern the social and even transcendental good which bridges divisive difference

A leader advocates for new cultural norms which accommodate diversity, social justice, and redress disempowerment

The leader as a transformative cultural advocate also needs an awareness of how to harness diverse forms of cultural capital which clients, workers and communities bring to educational endeavors.

Each of us has our own set of values that determine which aspects of life we regard as important or beneficial. Our values help determine our tastes, our way of life, our entertainment, our social, political and religious interactions.

Some of the values we hold may be 'superficial', transitory or fitting solely the moment in which we find ourselves. Other values are more fixed and may stay with us through our life; these are our 'core values'.

Our parents are a key influence upon our values as we grow as children. So, too, is any church or religious background we experience. Our society, our neighbors, friends and colleagues, too, can have an influence upon our values. So, too, can our teachers and our schooling.

Often, school can be a place of conflict for it is there that we experience other values perhaps for the first time. Some of the values we experience in school can be in conflict with or contradict the values of our parents. As we go through high school, we start to experience values in ourselves and our peers that conflict both with school and our parents. Conflicting and unfixed values can be a major problem for adolescent and teenage years.

As we grow in years and experience, our values become more fixed, especially a set of 6 to 10 'core' values. It is these core values that determine what is really important to us as an individual. The surprising thing is that if you ask most people what their values are, many would not be able to give you an answer.

A good many people are leading lives unconnected with their core values. This can lead to a life of unhappiness, discontent and lack of fulfillment. Sometimes it can lead to conflict. Often the person does not know why their life seems unhappy, unfulfilled and sometimes full of conflict. Often, the cause is that the life they are living is not in accordance with their personal values.

For some people a conflict can arise within them because they are trying to live a life according to the values of a company, an organization, a religious or political organization, the values of their friends or colleagues or partner, rather than living a life according to their own core values. In doing this, the values of the other people or organizations are being met but the person's own values are being left unfulfilled.

A person is not necessarily wrong to seek to support and fulfill the values of other people or organizations. However, leaving your own values unfulfilled can lead to frustration and unhappiness. A key issue in this, though, is that the person may believe they are “doing the right thing” by working to the values of others and yet still feel a sense of frustration and unfulfilment; -the reason being that they may be unaware of their own values or, maybe, feel guilty of their own values where they conflict with the values of others.

Goals of successful education include the development of capacities and confidence to conduct oneself responsibly in support of one’s own well-being; the ability to contribute to the well-being of others whose circumstances bar them from completing successful attainment of well-being for themselves; and facilitating the translation of the society’s beliefs and values to upcoming generations, ensuring community service and social justice are maintained and remain an integral part of society’s fabric (Arneson, 2007).

We can, whenever and wherever we choose, successfully teach all children whose schooling is of interest to us. We already know more than we need in order to do this. Whether we do it must finally depend on how we feel about the fact that we haven’t so far (Edmonds, 1990).

Collaboration is the only way we can guarantee consistently better results for all children. Attention to diversity in all its manifestations (language, culture, special needs, disability, sexual orientation, poverty, race, age, gender, and class) is a social justice priority, one that we have struggled with for way too long (Seattle’s

Superintendent, Maria Goodloe-Johnson, 2010)

It’s one thing to be an advocate focusing on the needs of underserved students. It’s another thing to build people’s will to address those issues. A lot of work is “insideout” – who I am and how I am, my journey, for me to be effective and develop why it is important for me to address issues of race, class, and culture in schools.

Building leadership capacity is essential in solving equity issues in schools (Tom

Malarkey, National Equity Project, 2010)

Anna, a Cape Verdean newcomer, is three years beyond her peers in terms of her science skills and knowledge. She arrives completely new to the English language

* Naming specific learning needs and gifts of children from underserved populations compels us as educators to develop a specialized professional knowledge and skills (Cultural Competency)

Hannah, a Polish American, is having difficulty communicating orally. Literacy diagnostics don’t indicate a language problem, and she’s great at painting. When her teacher probes, she learns that Hannah’s only parent is deaf and communicates through sign language; therefore

Hannah does not communicate orally at home.

Alejandro, a second-generation Mexican-American, speaks

Spanish at home. His teacher is challenged to identify how much Alejandro’s difficulty in math stems from language acquisition versus learning disability.