A Drop to Drink - Energy + Environmental Economics

advertisement

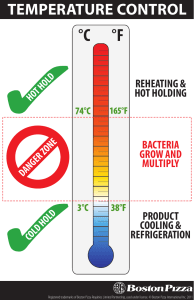

A Drop to Drink The Economic Case Against Policy Prohibition of CSP Wet Cooling Ben Haley Energy and Environmental Economics 101 Montgomery St., 16th Floor San Francisco, CA 94104 Agenda • • • • • Concentrating solar power and water CEC policy on water use for cooling Analysis Results Conclusions Source: N. Blair, Concentrating Solar Deployment Systems (CSDS) – A New Model for Estimating U.S. Concentrating solar Power Market Potential Source: EPRI, A Survey of Water Use and Sustainability in the United States with a Focus on Power Generation Dry Cooling~80 gallons/MWh Wet Cooling~800 gallons/MWh County Riverside Riverside San Bernardino San Bernardino Tulare Tulare CSP Capacity State Factor CA CA CA CA CA CA 0.25 0.43 0.25 0.43 0.25 0.43 2050 Capacity 15 15 15 15 1.3 1.3 Thousand Thousand AcreAcre% of County Feet/Year Wet Feet/Year Dry County Water Use if Cooled Cooled Water Use Wet Cooled 81 138 81 138 7 12 8 13 8 14 <1 1 1,124 1,124 314 314 2,698 2,698 7% 12% 26% 44% <1% <1% % of County Water Use if Dry Cooled <1% 1% 3% 4% <1% <1% Source: Congressional Research Service, Water Issues of Concentrating Solar Power (CSP) Electricity in the U.S. Southwest Why is cooling water so important for CSP plants? • Dry cooling towers have higher capital costs and parasitic loads • Hot, dry conditions (read: desert) mean a large temperature difference between wet and dry bulb temperatures, and thus higher efficiency losses • The most severe efficiency penalties occur on hot days coincident with summer peak loads • More important for parabolic trough than power tower CEC Siting Policy in Action • Beacon X • Genesis X • Abengoa CEC will approve wet cooling with potable resources if: • No recycled water is available • There are no negative environmental effects from usage (significant groundwater overdraft, etc.) • It can be proven that dry cooling makes the project economically unsound Policy Background California Constitution (Article X, Section 2) State Water Resources Control Board Resolution 75-58: Water Quality Control Policy on the Use and Disposal of Inland Waters Used for Power Plant Cooling California Water Code 13050 and 13552.6 Warren-Alquist Act 2003 Integrated Energy Policy Report NREL Solar Advisor Model (SAM) • Solar performance model combined with a financial model • Allows for inputs of various system characteristics (field size, turbine efficiency, etc.) • Allows modeling of both wet and dry cooling SAM Simulation Results Wet Cooling Dry Cooling Location Capacity Factor LCOE Incremental Cost Penalty Twenty Nine Palms AP 0.281 $0.1575 - Incremental Water Use (AF/Y) 2151 Imperial AP 0.283 $0.1601 - 2117 Barstow-Daggett AP 0.262 $0.1684 - 2027 Chino AP 0.209 $0.2243 - 1657 Blythe-Riverside County AP 0.271 $0.1654 - 2069 March AFB 0.244 $0.1894 - 1886 Riverside Municipal AP 0.212 $0.2208 - 1682 Palm Springs International AP 0.257 $0.1742 - 1992 Twenty Nine Palms AP 0.281 $0.1674 6.3% - Imperial AP 0.283 $0.1738 8.6% - Barstow-Daggett AP 0.262 $0.1784 5.9% - Chino AP 0.209 $0.2399 7.0% - Blythe-Riverside County AP 0.271 $0.1779 7.6% - March AFB 0.244 $0.2041 7.8% - Riverside Municipal AP 0.212 $0.2357 6.7% - Palm Springs International AP 0.257 $0.1869 7.3% - Ex. Water Cost Simulation ResultTwenty Nine Palms Airport $0.1720 $0.1700 $0.1680 LCOE $0.1660 $0.1640 LCOE Dry Cooled LCOE Wet Cooled $0.1620 $0.1600 $0.1580 $0.1560 $0 $500 $1,000 $1,500 $2,000 $2,500 $3,000 $3,500 $4,000 $4,500 Annual Cost of Water Volume ($/AF) Results Location Cost of Water Right Twenty Nine Palms AP $45,552 Imperial AP $65,178 Barstow-Daggett AP $45,628 Chino AP $69,092 Blythe-Riverside County AP $57,506 March AFB $67,331 Riverside Municipal AP $66,294 Palm Springs International AP $57,738 Cost of Committed Water Volume Annual Cost of Water Volume $1,518 $2,972 $2,173 $4,191 $1,521 $2,972 $2,303 $4,514 $1,917 $3,762 $2,244 $4,383 $2,210 $4,328 $1,925 $3,757 Water Transfers • 155 water transactions examined (20002009) from Water Transfer Database. Values recorded in terms of “committed water volume.” • Not a hugely active market • Compares short term and long-term transfers on an equal basis • Uses “average committed water volume” as a proxy for “anticipated firm committed water volume” $2,500 Water Transfers: Cost of Committed Water Volume (2000-2009) $2,000 $1,500 Maximum $/AF Weighted Mean CSP Plants $1,000 $500 $0 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 Sources: Pacific Institute, Waste Not Want Not Congressional Research Service, Water Issues of Concentrating Solar Power (CSP) Electricity in the U.S. Southwest Conclusions • All potential CSP plants demonstrate a higher value for water than do other users, according to recent market transactions. • The existence of potential water conservation is not reason enough to mandate it; hindering development of CSP projects is an uneconomic water conservation strategy. • Using potable water resources for cooling should continue to be assessed on a case-by-case basis. • The state’s water policies, or lack thereof, make cooling water use an added uncertainty for developers.