Chapter 9 Society and Politics in the Early Republic

Chapter 9

Society and Politics in the Early Republic

The American People , 6 th ed.

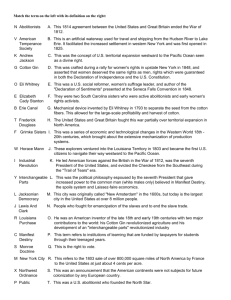

I. A Nation of Regions

The Northeast

The Northeast region stretched from eastern Pennsylvania and New Jersey to

New England.

Small family farms dotted the landscape and produced a surplus of goods.

People used the barter system for economic exchanges. Cash was rare.

The demand for heating fuel quickly depleted the region’s forests.

The South

The South stretch from Maryland to

Georgia along the coast, and west to the newly forming states of Alabama and

Mississippi.

Planters had experimented with a number of grains, but had little success until cotton was imported from Europe.

The invention of the cotton gin in 1793 allowed one laborer to clean up to 50 pounds of cotton a day.

Trans-Appalachia

The Trans-Appalachia region consisted of the lands west of established white settlement known as the “backcountry” or

“frontier.”

Settlers, drawn by the promotions of land speculators, moved west into the region in astounding numbers between 1790 and 1810.

The Nation’s Cities

Although most Americans lived on the land or in small villages, a growing number chose to live in the expanding cities.

The most aggressive urban growth was found in the Northeast due to established ports of commerce and booming economy.

In Trans-Appalachia, cities like Chicago and

Pittsburg began to spring up along the Great

Lakes and interior rivers.

Cities were relatively small, dangerous, and unhealthy.

II. Indian-White Relations in the Early Republic

The Goals of Indian Policy

From 1790 to 1830, the federal government established policies toward Native Americans ostensibly to integrate them into white society.

The Indian’s refusal to view themselves as a conquered people forced the government to deal with the tribes through land treaties.

Illegal infringement of tribal lands rarely ceased, always in the benevolent guise of education or

Christianization.

III. Perfecting a Democratic

Society

The Revolutionary

Heritage

Social reform was inspired by the democratic ideals of the Revolution.

Americans accepted the ideal of differences in wealth or social standing but could not tolerate the suggestion that such differences made some people better than others.

Race, Slavery, and the

Limits of Reform

In the South, the aggressive growth of cotton cultivation made the price of slave labor skyrocket.

Antislavery appeals from abolitionists all but disappeared, even from oncevehement religious groups and the nation’s capital.

Antislavery reform also weakened in the

Northeast.

IV. The End of Neo-

Colonialism

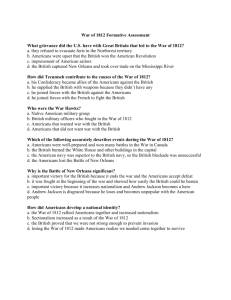

The War of 1812

War Hawks of Congress had tolerated enough of

Britain’s presence on American soil.

President Madison finally asked Congress for a declaration of war on June 1, 1812.

British forces occupied Washington in 1814, burning the Capital and presidential mansion.

Hostilities ended by the Treaty of Ghent on

Christmas Eve, 1814.

The United States and the Americas

President Monroe issued an 1823 statement on Latin

America, known today as the Monroe Doctrine:

The American colonies were closed to new exploration.

The political systems of the Americas were separate from those of Europe

The United States would consider hostile any influence from European powers.

The United States would refrain from interference in established colonies in the New World.

V. Knitting a Nation

Together

Conquering Distance

The beginnings of the transportation revolution helped to bring the nation together.

Travel and circulation of the printed word were the only ways of communicating across space.

New turnpikes, construction of the National

Road, canal building, and advances in steampowered ships helped quicken the spread of news.

Strengthening American

Nationalism

National pride during this era was shaped by the War of 1812 and the religious revivalism of the Second Great

Awakening.

Also important were landmark decisions by the Supreme Court regarding judicial review and supremacy of the federal government over the states.

The Specter of

Sectionalism

Despite the rampant nationalism following the

War of 1812, political unity in the nation was fragile.

Most divisive was the issue of slavery in the vast, new territory west of the Mississippi River.

Again, a compromise avoided disaster. The new state of Missouri was admitted to the

Union as a slave state and Maine was admitted as a free state.

VI. Politics in Transition

The Demise of the

Federalists

Following the War of 1812, the Federalists were plagued by accusations of disloyalty.

Federalists continued to believe that political leadership should be restricted to “the wise and the good.”

An increasingly hostile electorate eschewed traditional Federalist values and continued to turn to the party of Jefferson.

Division Among the

Jeffersonians

During the early years of the nineteenth century, the

Jeffersonian Republicans monopolized the nation’s presidency and legislature.

Their success was largely due to the decline of the

Federalists.

Trying to appeal to a broad base of Americans,

Madison’s administration began a program of nationally sponsored economic development through road and canal construction, protective tariffs, and the creation of the second Bank of the United States. Collectively, this plan was called the American System and began to draw criticism immediately.

Collapse of the Federalist-

Jefferson Party System

The final collapse of the party system was triggered by the election of 1824.

For the first time in years, there was active competition for the presidency from all directions.

After voting, none of the candidates received a majority, and a subsequent vote by the House elected John Quincy Adams even though Adams had trailed in original electoral votes.

As a result, Adams served his presidency under a cloud of suspicion and party politics began a process of realignment.