Sec16

advertisement

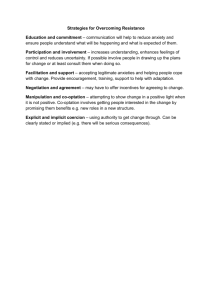

Success Strategies in Channel Management Managing Conflict to Increase Channel Coordination 1 Managing Conflict to Increase Channel Coordination Forms of Channel Conflict Assessing the Degree and Nature of Channel Conflict Measuring Conflict Styles of Conflict Resolution Accommodation Repeated Compromise Competition When Conflict Is Desirable When Is Conflict Functional? Collaboration Major Sources of Conflict Conflict Resolution Strategies Competing Goals Co-optation Differing Perceptions of Reality Third-Party Mechanisms Building Relational Norms Fuelling Conflict Clashes Over Domains Multiple Channels Information Exchange 2 Managing Conflict to Increase Channel Coordination Channel conflict is a state of opposition, or discord, among the organizations comprising a marketing channel. Conflict is a normal state in a channel. Indeed, a certain amount of conflict is even a desirable state: F or purposes of maximizing performance, a channel can be too harmonious. How can managers direct conflict to create functional channel outcomes? 3 Forms of Channel Conflict •Over-saturation/over-distribution •Stocking levels •Direct vs. individual channels •Regional vs. national distribution •Large account coverage •Split compensation •Sales quotas •Territories: geographic, value offer, or market specific •Market life cycle channel transition •New market development •New value offer launches •Channel tasks to be performed •Technology required •Training •Channel border skirmishes •The phantom channel/grey marketing •Refusal to be locked into one supplier •Overselling without regard to availability •Bureaucratic vs. entrepreneurial philosophies •Pricing issues •Sizes of profit margins/compensation •Competition over resources •Trans-shipping •Assigned markets The key factor is to manage conflict, not permit it to rage out of control. 4 Assessing the Degree and Nature of Channel Conflict The word conflict has negative connotations: contention, disunity, disharmony, argument, friction, hostility, antagonism, struggle, battle . . . the many synonyms are emotionally laden. In individual personal relationships, conflict is almost invariably viewed as something to avoid, a sign of trouble. Channel conflict arises when the behaviour of a channel member is in opposition to its channel counterpart. In contrast, competition is behaviour in which a channel member is working for a goal or object controlled by a third party (such as customers, regulators, or competitors). Competing parties struggle against obstacles in their environment. Conflicting parties struggle against each other.' Latent conflict is the norm in marketing channels. Inevitably, the interests of channel members collide as all parties pursue their separate goals strive to retain their autonomy, and compete for limited resources. 5 Nature of Channel Conflict In contrast, perceived conflict occurs when a channel member senses that some sort of opposition exists: opposition of viewpoints, of perceptions, of sentiments, of interests, or of intentions. Perceived conflict is cognitive, that is, emotionless and mental. It is a situation of contention. Conflict is often considered as a state: Conflict is also a process. It consists of episodes or incidents. How each episode is interpreted by the parties depends on the history of their relationship. A positive history creates a positive future: A new conflict incident will be downplayed or charitably interpreted. If not managed, perceived conflict can escalate quickly into manifest conflict. 6 Measuring Conflict The following example is from an assessment of how much conflict car dealers experience in their relationships with car producers.' Step 1: Counting Up the Issues. What are major issues of relevance to two par-ties in their channel relationship? It does not matter whether the issues are in dispute at the moment. What matters is that they are major aspects of the channel relationship. Step 2: Importance. For each issue, ascertain how important this issue is to the dealer. This could be done judgmentally or by asking dealers directly. Step 3: Frequency of Disagreement. For each issue, ascertain judgmentally or by collecting data how often the two parties disagree over this issue. Step 4: Intensity of Dispute. For each issue, ascertain judgmentally or by collecting data how intensely the two parties differ on the issue (how far apart the two parties' positions are). 7 Measuring Conflict There is no real argument over any issue if: The difference of opinion rarely occurs (low frequency). The issue is petty (low importance). The two parties are not very far apart on the issue (low intensity). If any of these elements is low, the issue is not a genuine source of conflict. When a relationship is complex, many issues arise. In general, the more roles a channel member assumes, the greater the scope for disagreements, and therefore the greater the potential for conflict. The combatants themselves are frequently unable to disentangle the sources of their friction.. Inflamed relationships lead people to double count issues; to overlook issues on which they do agree; and to exaggerate the importance, intensity, and frequency of their differences. 8 When Conflict Is Desirable Conflict is usually thought to be dysfunctional, to hurt a relationship's coordination and performance. Although this is generally true, opposition actually makes a relationship better on certain occasions. This is functional (useful) conflict. Their opposition leads them to: 1. Communicate more frequently and effectively 2. Establish outlets for expressing their grievances 3. Critically review their past actions 4. Devise and implement a more equitable split of system resources 5. Develop a more balanced distribution of power in their relationship 6. Develop standardized ways to deal with future conflict and keep it within bounds' 9 When Is Conflict Functional? From the downstream channel member's viewpoint, functional conflict is a natural outcome of close cooperation with a supplier. Working together to coordinate tightly inevitably generates disputes in ample measure. But when channel members are committed, these disputes serve to raise performance in the short term and do not damage the level of trust in the relationship. Cooperative relationships are inevitably noisy and contentious. The resulting conflict should be tolerated, even welcomed as normal. This functional conflict is even more likely if the downstream channel member has considerable influence over the supplier. 10 Are Peaceful Channels Better Channels? Much depends on the reason why conflict is low. Often, when channel members are not in opposition (low conflict), their relation-ship is not one of peace and harmony. It can be one of indifference. The two parties then do not bother to disagree about anything. There is no issue between them about which they have an opinion, no issue that is important to them or over which they care to invest the effort to argue. Conflict undermines channel commitment by damaging the focal party's trust in its counterpart. This powerful effect occurs in two ways. First, conflict directly and rapidly hurts the focal party's confidence in the counterpart's benevolence and honesty. Second, conflict reduces interpersonal satisfaction, which, in turn, delivers another blow to trust. 11 Major Sources of Conflict in Marketing Channels Most conflict is rooted in differences in (1) channel members' goals; (2) their perceptions of reality; and (3) what they consider to be their domains or areas where they should operate with autonomy. The most complex of these three sources of conflict is the last, because domain conflict has many sub dimensions. 12 Competing Goals Each channel member's set of goals and objectives is very different from those of other members. Resellers carry a supplier's line in order to maximize their own profits. They can do so by several routes: Agency theory underscores how competing goals create conflict in any principal – agent relationship, regardless of the personalities and players involved and regardless of the history of their relationship. Goal divergence, and subsequent conflict, is extremely common. (1) achieving higher gross margins per unit (pay the supplier less while charging the customer more), (2) increasing unit sales, decreasing inventory, (3) holding down expenses, and (4) receiving higher allowances from the producer. 13 Differing Perceptions of Reality Differing perceptions of reality are important sources of conflict, because they indicate that there will be differing bases of action in response to the same situation. As a general rule, channel members are often confident that they know "the facts of the situation." Yet, when their perceptions are compared, they are frequently so different that it is difficult to believe they are members of the same channel. Perceptions differ markedly, even on such basic topics as: What the attributes of the value offer or service are What applications it serves and for which segments What the competition is 14 Differing Perceptions of Reality Seldom do channel members co-operate fully enough to assemble the entire picture from their separate pieces. The solution to this problem is twofold. One is communication,. The other solution is for each organization to develop greater sensitivity to the business culture of the other channel member. 15 Clashes Over Domains Each channel member has its own domains, or spheres of function. Much conflict in channels occurs when one channel member perceives that the other is not taking proper care of its responsibilities in its appropriate domain. This can mean doing the job wrong, not doing the job at all, or trying to do the other channel member's job! Conflict is usually due to multiple causes.. Intra-channel Competition From the upstream viewpoint, the problem of domain clash occurs when a supplier sees its downstream partners represent its competitors. Of course, much of the time, they do so downstream partners frequently position themselves as providers of an assortment, and seek economies of scale by pooling demand for a class of value offers. 16 Multiple Channels Suppliers like multiple channels because they may increase market penetration and raise entry barriers to potential competitors. Many different channel types afford the supplier a window on many markets. In addition, many channel types are bound to compete with each other. Suppliers are prone to consider this competition "healthy," and sometimes they are right. Of course, customers like multiple channels when it means they can find a channel that meets their service output demands. The danger of multiple channels is the same as the danger of intensive distribution: Downstream channel members may lose motivation and can withhold support (a passive response), retaliate, or exit the supplier's channel structure (active responses). This is particularly the case when the customer can free ride, gaining services from one channel while placing its business with another. The ironic result is that, by adding channel types, the supplier may come to reduce, rather than increase, the breadth and vigour of its market representation. 17 What Suppliers Can Do An important issue is what responsibility suppliers have to protect their multiple channels from each other. Some suppliers, of course, often feel no regret, assume no responsibility, and take no action. Suppliers can offer more support, more service, more value offer, and even different value offer to different channel types in order to help them differentiate themselves Suppliers can try to manage the problem by devising different pricing schemes for different channels, which is also legally dubious. This creates an opportunity for arbitrage. The next section on grey markets shows how this can get out of control. A variation on this theme is to offer different brand names to different channels. Conflict over domains is one of the most visible and least tractable forms of opposition in marketing channels. 18 Fuelling Conflict Conflict Creates More Conflict Conflict creates more conflict. A major reason why it proliferates is that once a relationship has experienced high levels of tension and frustration, the players find it very difficult to set their acrimonious history aside and move on. Each party questions whether the other is capable of becoming committed to the relationship. Each discounts positive behaviours and accentuates negative behaviours by the other side. The foundations of trust are thoroughly eroded by high levels of conflict. 19 Threats To threaten means to imply that punishments, or negative sanctions, will be applied if desired behaviour or performance is not provided (i.e., if compliance is not forthcoming). The evidence is powerful that a strategy of repeated threats raises the temperature of a relationship by increasing conflict and by reducing the channel member's satisfaction with every aspect of the channel relationship. Coercive power is a tool, like a hammer. It can be put to positive purpose if used properly. As a general rule, both sides rely more heavily on non-coercive strategies, particularly when dealing with powerful counterparts. Important relationships encourage non-coercive influence attempts: Does this mean that channel members should never coerce each other? No the message is not that coercion should be ruled out. On occasion, organizations do need to raise the temperature of their relationships to improve channel performance. 20 Conflict Resolution Strategies Institutionalized Mechanisms Designed to Contain Conflict Early Information-Intensive Mechanisms Many of these mechanisms are designed to head off conflict by creating a way to share information. An information-intensive mechanism is risky and expensive: Each side risks divulging sensitive information and must devote resources to communication. Trust and cooperation are helpful conditions because they keep conflict manageable. 21 Co-optation Co-optation is a mechanism designed to absorb new elements into the leadership or policy-determining structure of an organization as a means of averting threats to its stability or existence. Effective cooptation may bring about ready accessibility among channel members because it requires the establishment of routine and reliable channels through which information, aid, and requests may be brought. Co-optation thus permits the sharing of responsibility so that a variety of channel members may become identified with and committed to the programs developed for a particular value offer or service. However, cooptation carries the risk of having one's perspective or decision-making process changed. It places an "outsider" in a position to participate in analyzing an existing situation, to suggest alternatives, and to take part in the deliberation of con-sequences. 22 Third-Party Mechanisms. Co-optation brings together representatives of channel members. In contrast, mediation and arbitration are ways to bring in third parties that are uninvolved with the channel. This mechanism prevents conflict from arising or keeps manifest conflict within bounds. Mediation is the process whereby a third party attempts to secure settlement of a dispute by persuading the parties either to continue their negotiations or to consider procedural or substantive recommendations that the mediator may make. Effective mediation succeeds in clarifying facts and issues, in keeping parties in con-tact with each other, in exploring possible bases of agreement, in encouraging parties to agree to specific proposals, and in supervising the implementation of agreements. 23 Building Relational Norms There is an important class of factors that serves to forestall or direct conflict and that management cannot simply decide to create. These are norms that govern how channel members manage their relationship. They grow up over time as a relationship functions. A channel's norms are its expectations about behaviour, expectations the channel's members at least partially share. In channels that are alliances, it is common to observe norms such as: Flexibility. Channel members expect each other to adapt readily to changing circumstances, with a minimum of obstruction and negotiation. 24 Information Exchange Channel members expect each other to share any and all pertinent information - no matter how sensitive - freely, frequently, quickly, and thoroughly. Solidarity. Channel members expect each other to work for mutual benefit, not merely onesided benefit. A channel with strong relational norms is particularly effective at forestalling conflict. It discourages the parties from pursuing their own interests at the expense of the channel. These norms also encourage the players to refrain from coercion and to make the effort work through their differences, thus keeping conflict in the functional zone. 25 Styles of Conflict Resolution Avoidance A relatively passive channel member (perhaps one in a weak position or represented by a poor negotiator) has an avoidance style of dealing with conflict. It attempts to pre-vent conflict from occurring by . . . failing to press for much of anything! Typically, the avoider wants to save time and head off unpleasantness. Accommodation Another style of dealing with conflict is to be accommodating to the other party, meaning to be more focused on its goals than on one's own. Unlike avoidance (a passive strategy), this is more than just another way of keeping the peace. Accommodation is a proactive means of strengthening the relationship by cultivating the other channel member. 26 Styles of Conflict Resolution Competition A strategy of competition (or aggression) involves playing a zero-sum game by pursuing one's own goals while ignoring the other party's goals. This approach focuses on pushing one's own position while conceding very little. Not surprisingly, this style aggravates conflict, fosters distrusts, and shortens the time horizon of the channel member’s vis-à-vis their relationship. Channel members tend to limit their usage of the aggressive style, especially in long-term relationships. Repeated Compromise A very different style is to compromise repeatedly, pressing for solutions that let each side achieve its goals, but only to an intermediate degree. This is a centrist approach that gives something to everyone; the compromise strategy seems to be fair. It is used often to handle minor conflicts, wherein it is easiest to get both sides to concede, thereby speeding the search for a resolution. 27 Collaboration The collaboration style of handling conflict requires a high level of resources, especially information, time, and energy. The problem solver tries to get both sides to get all their concerns and issues out in the open quickly, to work immediately through their differences, to discuss issues directly, and to share problems with an eye toward working them out. Problem solving requires creativity in trying to devise a mutually beneficial solution. It is an information-intensive strategy. In pursuing it, negotiators are sure to reveal a good deal of sensitive information, which could then be used against them. 28 Resolving Conflict and Achieving Coordination via Incentives What are the best arguments to use to persuade the channel member? Evidence indicates that economic incentives work extremely well, regardless of the personalities, the players, and the history of their relationship. Evidence shows that much of the acrimony can be dissolved by combining appealing economic incentives to participate with a payfor-performance system, and presenting the proposal through a salesperson who has a good working relationship with the retailer. 29