Wrath of God: Religious primes and punishment

advertisement

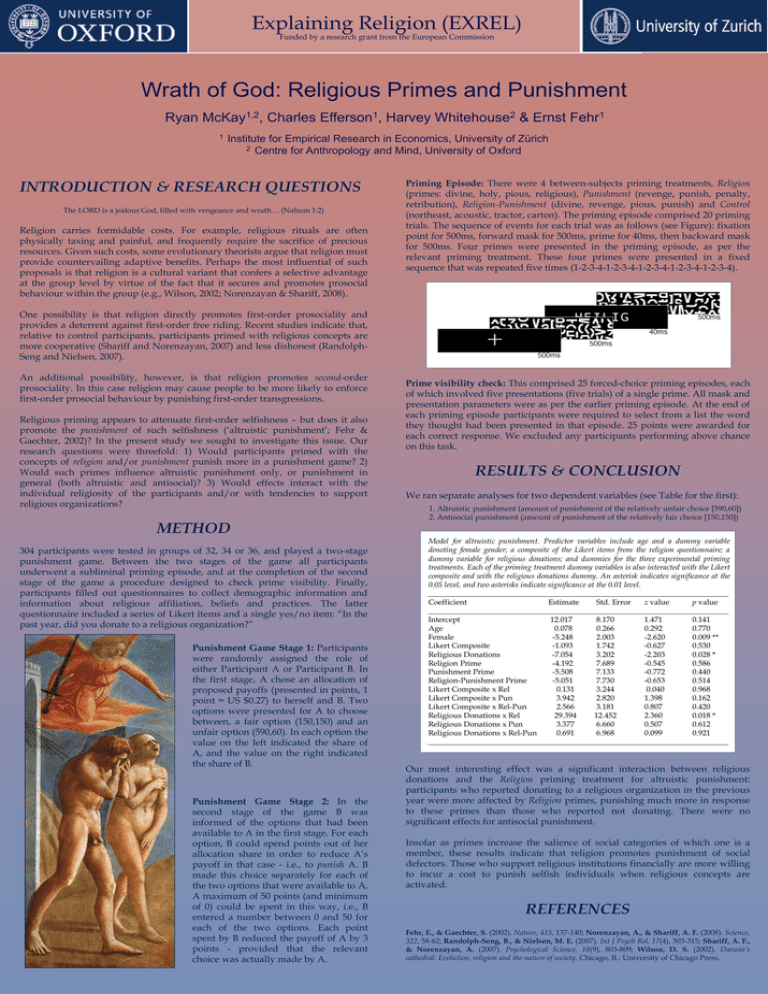

Explaining Religion (EXREL) Funded by a research grant from the European Commission Wrath of God: Religious Primes and Punishment Ryan 1,2 McKay , 1 Charles 1 Efferson , Harvey 2 Whitehouse & Ernst 1 Fehr Institute for Empirical Research in Economics, University of Zürich 2 Centre for Anthropology and Mind, University of Oxford INTRODUCTION & RESEARCH QUESTIONS The LORD is a jealous God, filled with vengeance and wrath… (Nahum 1:2) Religion carries formidable costs. For example, religious rituals are often physically taxing and painful, and frequently require the sacrifice of precious resources. Given such costs, some evolutionary theorists argue that religion must provide countervailing adaptive benefits. Perhaps the most influential of such proposals is that religion is a cultural variant that confers a selective advantage at the group level by virtue of the fact that it secures and promotes prosocial behaviour within the group (e.g., Wilson, 2002; Norenzayan & Shariff, 2008). Priming Episode: There were 4 between-subjects priming treatments, Religion (primes: divine, holy, pious, religious), Punishment (revenge, punish, penalty, retribution), Religion-Punishment (divine, revenge, pious, punish) and Control (northeast, acoustic, tractor, carton). The priming episode comprised 20 priming trials. The sequence of events for each trial was as follows (see Figure): fixation point for 500ms, forward mask for 500ms, prime for 40ms, then backward mask for 500ms. Four primes were presented in the priming episode, as per the relevant priming treatment. These four primes were presented in a fixed sequence that was repeated five times (1-2-3-4-1-2-3-4-1-2-3-4-1-2-3-4-1-2-3-4). One possibility is that religion directly promotes first-order prosociality and provides a deterrent against first-order free riding. Recent studies indicate that, relative to control participants, participants primed with religious concepts are more cooperative (Shariff and Norenzayan, 2007) and less dishonest (RandolphSeng and Nielsen, 2007). An additional possibility, however, is that religion promotes second-order prosociality. In this case religion may cause people to be more likely to enforce first-order prosocial behaviour by punishing first-order transgressions. Religious priming appears to attenuate first-order selfishness – but does it also promote the punishment of such selfishness (‘altruistic punishment’; Fehr & Gaechter, 2002)? In the present study we sought to investigate this issue. Our research questions were threefold: 1) Would participants primed with the concepts of religion and/or punishment punish more in a punishment game? 2) Would such primes influence altruistic punishment only, or punishment in general (both altruistic and antisocial)? 3) Would effects interact with the individual religiosity of the participants and/or with tendencies to support religious organizations? METHOD Prime visibility check: This comprised 25 forced-choice priming episodes, each of which involved five presentations (five trials) of a single prime. All mask and presentation parameters were as per the earlier priming episode. At the end of each priming episode participants were required to select from a list the word they thought had been presented in that episode. 25 points were awarded for each correct response. We excluded any participants performing above chance on this task. RESULTS & CONCLUSION We ran separate analyses for two dependent variables (see Table for the first): 1. Altruistic punishment (amount of punishment of the relatively unfair choice [590,60]) 2. Antisocial punishment (amount of punishment of the relatively fair choice [150,150]) 304 participants were tested in groups of 32, 34 or 36, and played a two-stage punishment game. Between the two stages of the game all participants underwent a subliminal priming episode, and at the completion of the second stage of the game a procedure designed to check prime visibility. Finally, participants filled out questionnaires to collect demographic information and information about religious affiliation, beliefs and practices. The latter questionnaire included a series of Likert items and a single yes/no item: “In the past year, did you donate to a religious organization?” Punishment Game Stage 1: Participants were randomly assigned the role of either Participant A or Participant B. In the first stage, A chose an allocation of proposed payoffs (presented in points, 1 point ≈ US $0.27) to herself and B. Two options were presented for A to choose between, a fair option (150,150) and an unfair option (590,60). In each option the value on the left indicated the share of A, and the value on the right indicated the share of B. Punishment Game Stage 2: In the second stage of the game B was informed of the options that had been available to A in the first stage. For each option, B could spend points out of her allocation share in order to reduce A’s payoff in that case - i.e., to punish A. B made this choice separately for each of the two options that were available to A. A maximum of 50 points (and minimum of 0) could be spent in this way, i.e., B entered a number between 0 and 50 for each of the two options. Each point spent by B reduced the payoff of A by 3 points - provided that the relevant choice was actually made by A. Our most interesting effect was a significant interaction between religious donations and the Religion priming treatment for altruistic punishment: participants who reported donating to a religious organization in the previous year were more affected by Religion primes, punishing much more in response to these primes than those who reported not donating. There were no significant effects for antisocial punishment. Insofar as primes increase the salience of social categories of which one is a member, these results indicate that religion promotes punishment of social defectors. Those who support religious institutions financially are more willing to incur a cost to punish selfish individuals when religious concepts are activated. REFERENCES Fehr, E., & Gaechter, S. (2002). Nature, 415, 137-140; Norenzayan, A., & Shariff, A. F. (2008). Science, 322, 58-62; Randolph-Seng, B., & Nielsen, M. E. (2007). Int J Psych Rel, 17(4), 303-315; Shariff, A. F., & Norenzayan, A. (2007). Psychological Science, 18(9), 803-809; Wilson, D. S. (2002). Darwin’s cathedral: Evolution, religion and the nature of society. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.