Why Quality

advertisement

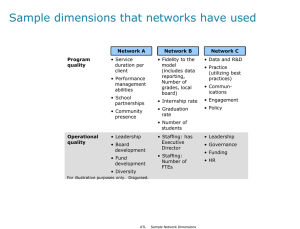

Why Quality Daniel F. Perkins Penn State University Professor of Family and Youth Resiliency and Policy Evidence-based and Evidence Informed Programs/Practices • Theoretically sound innovations evaluated using a well-designed study (randomized controlled trial or quasi-experimental design) and have demonstrated significant improvements in the targeted outcome(s). • Evidence-informed is the integration of experience, judgment, and expertise with the best available external evidence from systematic research. Distinguishing groundless marketing claims from reality The Problem: All sorts of “interventions” are available out there. EBP work, but .. • Research has shown that most aren’t being implemented with sufficient quality or fidelity • In 500 schools and 14 types of programs, 71% of content was delivered, but only half of the programs followed recommendation implementation practices. (Gottfredson & Gottfredson, 2002) • Very few programs measure or monitor implementation quality Positive Program/Practices Outcomes ≠ Effective Implementation • The usability of program or practice has nothing to do with the weight of the evidence regarding it – Evidence on effectiveness helps you select what to implement for whom – Evidence on outcomes does not help you implement the program Why focus on implementation? • Programs will likely show no effect when implemented poorly • Quality implementation is linked to better outcomes • Quality implementation does increase the probability of sustainability Implement Innovations INTERVENTION IMPLEMENTATION Effective High Quality Low Quality Good Outcomes for Consumers Undesirable Outcomes NOT Effective Undesirable Outcomes Undesirable Outcomes (Institute of Medicine, 2000; 2001; 2009; New Freedom Commission on Mental Health, 2003; National Commission on Excellence in Education,1983; Department of Health and Human Services, 1999) • Evidence-based programs/practices are most effective when they are implemented with Quality • High Quality = Fidelity = the practitioners use all the core intervention components skillfully FIDELITY COMPONENTS • Adherence: delivered the way it is designed with correct protocols and trained staff • Exposure/Dosage # of sessions delivered, length and frequency • Quality of Program Delivery ways in which staff deliver it (skills and attitude) FIDELITY COMPONENTS • Reach: the proportion of intended partcipants who actually participated in the program • Participant Responsiveness: the extent to which participants are engaged in the programme (attendance, + reactions) Percent Smoking (Weekly) Life Skills Training Program: Effects of Fidelity on Smoking 30% 25% 20% 15% 10% 5% 0% 27.0% 22.0% 19.5% Control Group Full Experimental Group High Fidelity Group 6 year follow-up data; Baseline data N= 5,954 7th Grade Students (56 schools) Full Experimental Group: N=3,597 12th Grade Students (60% of baseline sample) High Fidelity Group: N= 2,752 Data from Botvin, Baker, Dusenbury, Botvin, Diaz 12% 9.9% 9.1% 10% 8% 5.4% 6% 4% 4.2% 3.1% 4.1% Baseline Year One 2% en Im ig h H Lo w Im pl pl e em m C en ta tio on tro ta tio n n 0% l Percent Used Marijuana MPP: Effects of Fidelity of Implemetation: Marijuana Used in Last Month (N=42 Schools*) *Approximately 5,000 6th and 7th grade students @ baseline and follow-up Data from Pentz, Trebow, Hansen, MacKinnon, Dwyer, Johnson, Flay, Daniels, & Cormack Why does Quality matter? • Research has clearly linked quality of implementation with positive outcomes – Higher fidelity is associated with better outcomes across a wide range of programs and practices (PATHS, MST, FFT, TND, LST and others) • Fidelity enables us to attribute outcomes to the innovation/intervention, and provides information about program/practice feasibility The reality…. • Quality takes real effort because fidelity is not a naturally occurring phenomenon – adaptation (more accurately program drift) is the default • Most adaptation is reactive rather than proactive thereby weakening rather than strengthening the likelihood of positive outcomes Improving Quality Locally • Good pre-implementation planning • Improve practitioner knowledge of program/practice theory of change • Build a sustainable infrastructure for monitoring implementation fidelity and quality • What gets measured matters • Build internal capacity AND desire Why Monitor Implementation? • To ensure that the program is implemented with quality and fidelity to the original design. • To identify and correct implementation problems. • To provide “lessons learned” for future implementation efforts. • To identify and celebrate early successes. Keys to Quality Implementation • Support of site administrators • Qualified implementers who support the program • Ongoing planning meetings and community of practices • A detailed implementation plan (who, what, where, when and how) • Ongoing monitoring and technical assistance We are Guilty of many errors and many faults, but our worst crime is abandoning the children, neglecting the fountain of life. Many of the things we need can wait. The child cannot. Right now is the time his bones are being formed, his blood is being developed. To him we cannot answer ‘Tomorrow.’ His name is ‘Today.’ Gabriela Mistral, Nobel Prize-winning Poet References • • • • • • • • • Community Anti-Drug Coalitions of America (2007). Sustainability Primer: Fostering Long Term Change to Create Drug Free Communities. Washington, DC: Office of National Drug Control Policy. Goodman, R. M., & Steckler, A. (1989). A model for the institutionalization of health promotion programs. Family and Community Health, 11, 63-78. th, 11, 63-78. Johnson, K., Hays, C., Center, H., & Daley, C. (2004). Building capacity and sustainable prevention innovations: A sustainability planning model. Evaluation and Program Planning, 27, 135-149. Mancini, J. A., & Marek, L. I. (2004). Sustaining community-based programs for families: Conceptualization and measurement. Family Relations, 53, 339-347. Marek, L., Mancini, J.A., Earthman, G. E., & Brock, D. (2003). Ongoing Community-Based Program Implementation, Successes, and Obstacles: The National Youth at Risk Program Sustainability Study . Blacksburg, VA: Virginia Cooperative Extension. http://www.ext.vt.edu/pubs/family/350804/350-804.html Marek, L. I., Mancini, J. A., & Brock, D. J. (1999). Continuity, success, and survival of communitybased projects: The national youth at risk program sustainability study (Virginia Cooperative Extension Publication 350-801). Retrieved September 6, 2003, from http://www.ext.vt.edu/pubs/family/350-801/350-801.html Scheirer, M. (2005). Is Sustainability Possible? A Review and Commentary on Empirical Studies of Program Sustainability. Americal Journal of Evaluation, 26, 320-347. Shediac-Rizkallah, M. C., Scheirer, M. A., & Cassady, C. (1997, May). Sustainability of the Coordinated Breast Cancer Screening Program (Final report to the American Cancer Society). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University School of Hygiene and Public Health. Small M. (2004). Sustainability planning. A presentation made at the annual PROSPER Statewide Meeting University Park: Prevention Research Center, The Pennsylvania State University.