Does the Truth set you Free?

advertisement

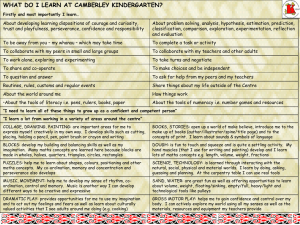

Does the Truth set you Free? Imagination as a disabling and enabling force in Neil Jordan’s The Butcher Boy and Jim Sheridan’s In America. Imagination: triggered by, and the cause of, trauma 2 examples from the Irish film industry where imagination becomes detached from/a substitute for reality This happens due to love, loss, disillusionment and depression and can lead to mental trauma Resort to imagination in the forms of escapism, self-deception, fantasy, and an inability to confront reality Mór Anguished – Nuala Ní Dhomhnaill Mór, firmly under lock and key In her own tiny mind (2” x 4” x 3”) of grey, pinkish stuff (here be the wounds that drown the flies While other flies survive To make their maggots On the carrion fringe) The magpies and the crows That come at evening To upset their guts, “every one’s enclosed In their own tiny hells.” The small birds Scatter and spread When she flings up at them A sod of earth. “Listen, in God’s name,” she begs Rogha Dánta, trans. By Michael Hartnett The Butcher Boy Dir. Neil Jordan used Mary to show the ‘mixture of paranoia and paralysis, madness and mysticism’ present in Ireland at the time (Qtd. In Cullingford 193) ‘not a source of comfort but a malevolent hallucination, a fragmented image of imprisonment and disconnection’ (Cullingford) In America ‘if you can’t touch somebody you created how can you create somebody that will touch anybody?... Acting Johnny. And bringing something to life, it’s the same thing. That’s why you can’t get a job acting Johnny, because you can’t feel anything’ “Imagination Inflation” Stephanie J. Sharmann et al., The American journal of Psychology (2004). ‘with each imagining they create more perceptual detail. As a result the imagined event becomes increasingly like memory for a genuine experience and subjects become increasingly likely to confuse imagination and reality’ Magic Realism Magic Realism: Imagination at the level of form Mateo – primal and alien, ‘Other’ Cross under water to get to city – sense of the unreal Looks at camera and says ‘this isn’t real’ 3 Wishes Camera PoV shots Halloween Love and Loss Love object - ‘images of his lost emotional life, the absence of mothering and friendship’ (Cullingford) Love & Loss: catalysts for imagination and escapism Mother figure Search for identity Emotional crippling hinders Johnny’s acting ‘Such Nostalgia Turns Sour’ (Scaggs) Places Mother on a pedastle ‘It wasn’t always like this’ (Francie’s Father) Pop Culture saturation and aspiration loses sense of identity when he looses sense of his past, becomes ‘Francie Pig’ each new loss/revelation breaks him down Truth and Freedom Confrontation with/realisation of the truth for Francie proves devastating – becomes a slave to his primal view of the world Francie’s Imagination lets him escape the truth momentarily but makes the eventual confrontation more traumatic Disillusionment Paralysis and emotional stasis Cultural Memory Aisling/Fís And Freedom, ooh Freedom. Well that’s just some people talking. Your prison is walking through this world alone… You’d better let somebody love you before it’s too late Mary as perverted Aisling Love object ‘dramatic loss of identity and meaning’ (Eyerman) Identifies himself in opposition to Ms Nugent Narrative Authority Frame within a frame and PoV shots destabilise Narrative authority Christie’s camcorder, Francie’s visions Narrators The media and the making of modern memory Family Familial support makes Johnny’s confrontation with the truth a liberating experience Both protagonists are unwilling to accept the loss of a family member Stable family ultimately helps Johnny recover ‘don’t worry Da, I won’t let them near us. See, I love you Da.’ Conclusion and Catharsis Francie Mary/his own subconscious guides him towards disaster Disabling: Paralysis, can’t accept reality, when he sees it it’s through his own emotional lens Enabling: allows him to deal with a troubled home life Johnny Escape from trauma/repetition Redemption, death/sacrifice, renewal Disabling: emotional paralysis, makes trauma more intense Enabling: ultimately Cathartic. Family & financial support Bibliography Cullingford, Elizabeth. “Virgins and Mothers: Sinéad O’Connor, Neil Jordan and the Butcher Boy.” The Yale Journal of Criticism 15:1 (2002): 185-210 Eyerman, Ron. “ The Past in the Present: Culture and the Transmission of Memory.” Acta Sociologica 47:2 (2004): 159-169 Gibbons, Luke. Field Day Esays: Transformations in Irish Culture. Cork: Cork Univeristy Press, 1996. “Limerick Rural Survey: Third Interim Report, Social Structure.” Maynooth, 1962. McCabe, Patrick. The Butcher Boy. Dublin: Paperview in asociation with the Irish Independent, 2005. Newhall, Beth. “‘Ebony Saint’ or ‘Demon Black’? Racial Stereotype in Jim Sherridan’s In America.” in Film History and National Cinema: Studies in Irish Film 2. Ed. John Hill, Kevin Rocket. Dublin: Four Courts Press, 2004. 143-153. Ní Dhomhnaill, Nuala. Selected Poems: Rogha Dánta. Trans. Michael Hartnett. Dublin: New Island Books, 2004. Scaggs, John. “Who is Francie Pig? Self-Identity and narrative reliability in The Butcher Boy.” Irish University Review 30:1 (2000): 51-58. Sharmann, Stefanie J., Gary, Maryanne, Beuke, Carl J. “Imagination Exposure and Imagination Inflation.” The American Journal of Psychology 117:2 (2004): 157-168. Winkelman, Donald M. “The Butcher Boy.” Western Folklore. 21:3 (1962): 186-187. Filmography The Butcher Boy. Dir. Neil Jordan. Perf. Stephen Rea, Fiona Shaw, Eamonn Owens. Warnerbros, 1997. DVD. In America. Dir. Jim Sheridan. Perf. Paddy Considine, Samantha Morton, Sarah Bolger, Emma Bolger, Djimon Hounsou. 20th Century Fox, 2002. DVD.