PPT - Muskie School of Public Service

advertisement

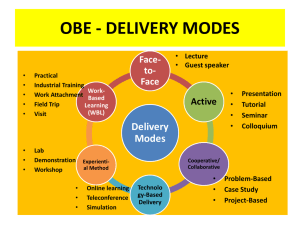

Getting to Outcomes: An Approach to Implementing Systemic Change Anita P. Barbee, MSSW, Ph.D. Consultant NRCOI and NCIC Christine Tappan, MSW Administrator, DCYF/DJJS Bureau of Organizational Learning & Quality Improvement Outline of Talk • • • • Background about the GTO model What is GTO? Review of the model Usefulness of GTO for child welfare, in general Usefulness of GTO for practice model installment and implementation, in particular • Past experience installing and implementing practice models in other states • Experience of using GTO in New Hampshire 2 Background of GTO • This framework is embedded in empowerment evaluation theory (Fetterman & Wandersman, 2005) and uses a social cognitive theory of behavioral change (Ajzen & Fishbein, 1977, Bandura, 2004) • It has the advantage of being a results -based accountability approach to change that has been used in smaller organizations to aid them in reaching desired outcomes for clients in such areas as preventing alcohol and substance abuse among teens as well as developing assets for youth (Fisher, et al, 2007) and teen pregnancy prevention (Lesesne et al, 2008). 3 Evidence of GTO effectiveness • Using a longitudinal, quasi-experimental design, Chinman et al (2008) examined the impact of using GTO on improvements in individual capacity to implement substance abuse interventions with fidelity and on overall program performance in programs that did and did not utilize a GTO approach. • They found the programs utilizing a GTO approach performed significantly better at both the individual and program levels than those that did not utilize the GTO approach. 4 10 STEPS IN GETTING TO OUTCOMES 1) Identifying needs and resources, 2) Setting goals to meet the identified needs, 3) Determining what science based, evidence based (EBP) or evidenceinformed practices or casework practice models exist to meet the needs, 4) Assessing actions that need to be taken to ensure that the EBP fits the organizational or community context, 5) Assessing what organizational capacities are needed to implement the practice or program, 6) Creating and implementing a plan to develop organizational capacities in the current organizational and environmental context, 7) Conducting a process evaluation to determine if the program is being implemented with fidelity, 8) Conducting an outcome evaluation to determine if the program is working and producing the desired outcomes, 9) Determining, through a continuous quality improvement (CQI) process, how the program can be improved and 10) Taking steps to ensure sustainability of the program. 5 GTO Support System Model Tools + #2 Goals To Achieve Desired Outcomes #3 Best Practices Training + #4 Fit #1 Needs/ Resources Assessment Current Level of Capacity #5 Capacities = + #10 Sustain #6 Plan #9 Improve/ CQI QI/QA + #8 Outcome Evaluation Actual Outcomes Achieved #7 Implementation & Process Evaluation TA + 6 Usefulness to Child Welfare • Already the GTO model has been used to implement programs to prevent teen pregnancy, teen violence and teen substance abuse, which are issues facing our clients. 7 Wandersman (2009): Keys to intervention success • Any effective model, program or intervention must have four keys to success: 1) A theoretical base including a theory of change 2) A fully articulated set of actions and skills that can be observed for presence and strength 3) System supports 4) Evaluation results including data benchmarks to monitor the efficacy of the model 8 Usefulness of GTO to Practice Model Installation and Implementation • First let’s review what a practice model is • Then we can go through examples of the issues of installing and implementing a child welfare practice model • Then we can see some of the issues that get agencies stuck in rolling out such a complicated initiative 9 A child welfare casework practice model A practice model for casework management in child welfare should be theoretically and values based, as well as capable of being fully integrated into and supported by a child welfare system. The model should clearly articulate and operationalize specific casework skills and practices that child welfare workers must perform through all stages and aspects of child welfare casework in order to optimize the safety, permanency and well being of children who enter, move through and exit the child welfare system. 10 Theory of Practice • Delineates how to think about or conceptualize the practice with the population of focus. The theoretical foundation can respond to four areas: 1) The conceptualization of the problem (e.g., child maltreatment is embedded in the stage of a family’s life development) 2) The change theory that informs how that problem can be remediated (e.g., self efficacy theory) 3) The theory that guides the critical contribution and influence of the relationship alliance or partnership (e.g., solution focused theory) 4) The core practice values that underlie the approach to clients and the problem (e.g. family centered or strengths based). 11 Specific Skills • A casework practice model should specify the practice skills that are to be carried out and measured for fidelity and implementation adherence. These include: 1) Core practice skills that guide practice across the life of a case (e.g., engagement, assessment, planning, decision making) so that even when there is no direction about a specific type of encounter, the theory and meta-skills together can guide practice 2) Clearly specified and distinct practice skills for each stage of a child welfare case including intake, investigation, in-home services, placement into and monitoring of progress in out-ofhome care (reunification, foster care recruitment and certification, adoption) 3) Specific skills for dealing with distinct family issues as child sexual abuse, neglect, or domestic violence involvement. 12 Infrastructure to Support Practice and Change Effort • The third component involves the ability to create a system infrastructure that supports and reinforces the theoretical orientation and practice skills that are a part of the practice model. This would include: 1) Policy, training, documentation requirements and forms, a SACWIS System (IT) 2) Supervision and worker performance evaluations that align with the casework practice model 3) Quality Assurance (QA) and continuous quality improvement (CQI) processes that align with and evaluate adherence to the casework practice model. The importance of systems alignment and a list of drivers of systems change has been supported by research in other fields of practice, collected in the NIRN model (Fixsen,et al, 2005) and by research on implementation in child welfare (Cahn, 2010). 13 Evaluation • The fourth component involves development of data points to monitor fidelity to the model and, once fidelity is achieved, to evaluate the impact on outcomes, in this case for children and families in the child welfare system. 1) Process or Implementation Evaluation assessing fidelity to the model is essential before embarking on outcome evaluation 2) Benchmarks important in child welfare would include the federal Child and Family Services Review outcomes of safety, permanency and well-being as well as other intervening or process measures that may be relevant (e.g. employee retention, engagement of community partners, and so on). 14 Experiences Installing and Implementing one Practice Model: Solution Based Casework • • • • Kentucky Washington Florida New York City 15 Using GTO in New Hampshire: Perspective of the State Administrator and Evaluator • Formation of an Implementation team • Step 1 of GTO: Assessing Needs o “What are the underlying needs and conditions that must be addressed by the casework practice model?” o This is a process of defining and framing the issue, problem or condition. o Usually, public child welfare agencies are faced with failures in outcomes of safety, permanency and wellbeing among children who come into contact with the child welfare agency. 16 Goal Setting • Step 2 of GTO: Setting Goals o “What are the goals and objectives that, if realized, will address the needs and change the underlying conditions?” o This, of course, is the process of identifying goals and objectives for meeting the identified need and can quickly lead to the search for information prescribed in the third GTO step. o Many states include these goals in their Program Improvement Plan (PIP) or bi-annual Child and Family Service Review (CFSR) or IV-B Plan or through a Consent Decree. o This is where values of how to practice with families begin to emerge. NH used a learning organization and solution focused lens to approach changes in their child welfare system. 17 Choosing an EBP or EIP • Step 3 of GTO: Choosing an evidence informed practice model o “Which science- based, evidence -based or evidence- informed casework practice models or best-practice programs can be used to reach our goals?” o To choose which casework practice model is best for the state and the workforce that the state can afford, a review of the literature may yield casework practice models that have evidence of positive impact for client families. o Ideally in this step, multiple models would be available to be studied and a model could be chosen to address the identified needs and goals for improvement. o Consultants, national technical assistance providers from federal, private, or philanthropic initiatives, and university partners may provide assistance in identification of a practice model or a specific practice for a specific issue. o In the case of NH, Chris Tappan attended a talk by Anita Barbee about Practice Models with an emphasis on Solution-Based Casework in May, 2010 for key training directors in New England. 18 Assessing Fit • Step 4 in GTO: Assessing the fit of a model to the agency culture o Leadership support is one of the first aspects of fit. In order to adopt a casework practice model, agency leadership must make a clear commitment to the model and express that commitment both inside the organization and outside with external community partners (e.g., Martin, et al, 2002). o This expressed commitment is facilitated by firsthand experience with understanding the model from the beginning. o In NH, Dana Christensen gave a presentation on SBC to leaders and implementation team members which gave them a glimpse of how certain segments of the system might react to the model and its implications, hear answers to potentially challenging questions, and understand important implementation challenges as well as test its core strength of support. 19 Renaming or Expanding the Model o “What actions need to be taken so that the selected program, practice, or set of interventions fits our child welfare agency?” o At this point, the organization has to assess adoption (fit) issues and possible adaptations of parts of the model that are not core components (Fixsen, et al, 2005). o For example, the team may find a name that brands the model for that state or jurisdiction, while still acknowledging the original source, (e.g., SBC was called Family Solutions for a while in Kentucky) or changing aspects of the existing model to accommodate cultural groups which are particular to the state. o For example Solution Based Casework was developed in Kentucky, a state without any recognized tribes. When Washington state adopted the SBC practice model, tribal input was included in the process of implementation. o NH also is incorporating Family Team Meetings into their new practice model (as we did in Kentucky) – Known now as “SolutionBased Family Meetings”. 20 Recognition of Systems Change o A significant challenge of this step is the stakeholder’s progressive realization that in order to change practice in the field, so many aspects of the system's infrastructure must change to facilitate the new practice. o Many of these systems cannot be changed before those who would change the systems fully understand the new practice and its implications. o In every state, there has been a naturally occurring tension between the need for infrastructure change (information systems, policy, supervision, quality assurance), and the desire to train the personnel who provide the direct practice. o Training typically occurs first because o 1) often the degree of system change is at first underestimated, o 2) training is easier to accomplish quickly and improves worker acceptance of infrastructure change, and o 3) infrastructure change is more challenging due to costs, past financial investment in old systems, and past administrative investment. o In NH training occurred first but some systems changes were implemented immediately. A clear communication plan about the roll out followed. 21 Assessing Organizational Capacity • Step 5 of GTO: Assessing Organizational Capacities o This includes assessing the organizational capacity for change in two major areas: o The human capacity (identifying potential champions for the change, as well as clinical skills of staff, as well as where resistance may lie) and o The organizational capacity (facilitators of change, and barriers to change), referred to by other models (Fixsen, et al, 2001) as ‘infrastructure’ changes. 22 NCIC Support and Culture and Climate Assessment • In NH, the implementation of the practice model coincided with an Implementation Project sponsored by the NCIC with funding from the Children’s Bureau. • Early adopters were trained in the model to spread the “good news” about SBC. • In addition, The assessment of human resource capacity should include an assessment of the clinical skills of workers and their ability to implement the casework model as designed. • Some providers have the characteristics of self efficacy, openness to change, and readiness to implement a practice model and some do not, thus an assessment of readiness/openness to EBP (Aarons, 2004) and a readiness to learn (Coetsee, 1998) should be conducted as a part of the early organizational culture and climate check. • In NH such an assessment of organizational culture and climate was conducted. 23 Organizational Capacity • Organizational capacity must be assessed for the ability to support the casework model. It is in this phase that the stakeholder team may need to work on ways to help the agency 1) enhance agency and system leadership, particularly help leaders create a vision and support for the change effort, 2) assess and help to change the organizational culture so that it is a learning environment that is open to and ready for change, 3) engage, train, and retain a more qualified and motivated workforce using participatory approaches such as appreciative inquiry (Cooperrider, 1996) and empowerment evaluation (Fetterman & Wandersman, 2005) to achieve the support needed for transformational change, 4) build cross-functional and cross-organizational teams to achieve change in policy, practice, process, and personnel, 5) identify the resources and other infrastructure to bring about the change on top of day to day duties, and 6) communicate results of quality improvement and change efforts to continue the momentum of these efforts. • NH had a healthy organization and capacity in place to implement a new practice model 24 Resources • Another part of assessing capacity is to find the organizational resources that will be needed to implement the plan. It is here that the child welfare organization will need to study how to adapt systemically to the needs of the new practice model by making progress on the time-consuming infrastructure changes. Some of the issues that typically emerge are the a) financial and personnel resources to support the new practice, b) rewriting of policy, c) criteria revisions for quality assurance and CQI procedures, and d) model- specific training for administrators, managers, and front line supervisors. • In NH the IP through NCIC helped with resources and policy, QA and CQI are adjusting to adapt to the new model. • In addition NH conducted special training for all levels of the organization with a coaching/case consultation reinforcement component to ensure supervisors are helping workers change practice. Changes in SACWIS will come later. 25 Planning • Step 6 of GTO: Implementation Planning Steps o The assessments will lead the implementation team to the development and implementation of two specific and long range plans: 1) a plan to train and maintain staff competency in the new practice model, and 2) a plan for infrastructure change to support the new practice model. Typically, jurisdictions quickly recognize the need for the first (training staff). However, it is equally important (and more difficult) to develop and implement a plan for the related agency infrastructure changes necessary to support the practice model (e.g. changes in policy, information systems, quality assurance, and staff evaluation). NH created both plans. 26 Stages of Training the Model Across the System 1) Train Leadership 2) Development of a comprehensive transfer of training program • A training of trainers (TOT) and/or a training of key experts who will provide mentoring on the use of the model, reinforce key concepts in the model and trouble-shoot where questions and concerns are raised must be conducted to insure that internal expertise is developed. These can be supervisors, managers, workers and trainers. In NH these consist of trainers, supervisors and administrators 27 Training (continued) 3) A pilot group of front line supervisors needs to be trained so they can become coaches to other supervisors and workers 4) Train the pilot front line workers in the practice model and reinforce through case consultation with their pilot supervisors • In NH, training of both supervisors and staff occurred statewide, and more certification is occurring first in PIP designated “Advanced Practice Sites”. 28 Training (continued) 5) Train the remainder of the supervisors in both the practice model and the case consultation model as well as the front line workers • At this point the new worker training and other support trainings need to be revised to incorporate the practice model • That is what NH did once everyone was trained. They also are aligning their training evaluation across trainings with an emphasis on assessing knowledge and skill development in the model and transfer of learning to the field. 29 Training (continued) 6) Evaluate the training and case consultation to ensure learning and transfer are occurring. This helps in establishing fidelity to the model. • As noted before, NH is expanding their training evaluation to align with the new model and its implementation 7) Training of and giving presentations to community partners to engage them in the new practice. • NH involved CASA, Resource Parent Training, the Courts and Juvenile Justice 30 Plans for Changing the Infrastructure • Use outside funds, reallocate existing funds, ask for additional funds to ensure that the financial and personnel resources that are needed can be put into place • Re-write policy • Increase and modify the curriculum and delivery mode of training (provide materials for learning, coaching and mentoring) • Conduct evaluation • Educate other organizational partners 31 Change the Computer System – Computer and paper systems that support practice need to change to accommodate the new practice model. – New forms, assessment tools, case planning tools (e.g. prevention plans, safety plans, in home treatment plans, out of home care plans, aftercare plans), case monitoring or progress tracking tools, and closure tools need to be modified or added and old tools need to be deleted so that the new ways of practice are not competing with the old ways. – It has been our experience that forms play an underestimated role in shaping worker behavior in the field. Workers tend to gravitate their sequencing of questions based upon the order of the form they are filling out, or will have to fill out once back in the office. – It is better to change the form to be conceptually consistent with the practice model than to expect to train the worker to resist the structuring pull of the old form. NH has redesigned the Bridges (SACWIS) system to drive a SBC lens from SDM through the “life of a case”. Rollout fall 2012 32 Change the CQI/QA tool and potentially increase CQI case reviews The CQI/QA system needs to align the case review tool, not only with the CFSR tool, but also with the new casework practice model components. • The new practice model components should be incorporated into the case review tool. This is essential for measurement of: a) the fidelity of daily practice to the model, b) the impact of adherence to the model on outcomes of safety, permanency, and well-being, c) the levels of adherence to the model statewide and by area, county, team, and individual which will, in turn, aid in determining training and supervision needs, and d) the impact of the model on outcomes. • In order to have enough data to track adherence and outcomes, some states may need to conduct CQI case reviews more frequently in order to have enough data to make judgments about how the process is going. An inexpensive way to do this is to involve front line supervisors and specialists as well as quality assurance personnel in a randomized case review process. NH is incorporating measures of the practice model into their case review Tool by August 2012. Case Practice Reviews occurring in 2012 have already shown increased levels of family engagement as measured by the OSRI. 33 Assessment and Realignment of Caseload and Workload • A final but critical infrastructure issue that must be considered is worker caseload size and overall workload. • A study of caseload including creation of a complex formula to assess caseload (for example taking into consideration the number of front line workers that are on leave or out for disciplinary measures) and workload sizes (for example assessing the number of out of home care cases workers are carrying as well as number of additional tasks a worker is executing above those in their caseload) may need to be enacted in order to assure that each worker meets the standards that produce the best outcomes in their state or the CWLA standards for caseload size (CWLA, 2008). In NH the organizational climate and culture study found workers were not overly stressed and that the workload was not overly burdensome. Continuing to monitor with annual survey under guidance of Workforce Development Committee and PM Evaluation Team. 34 Process or Implementation Evaluation • Step 7 of GTO: Process Evaluation. While the practice model is being piloted and rolled out across the state, there needs to be a process evaluation to answer questions such as, o “Is the practice model being implemented as it was intended? o Is the practice model being implemented with fidelity? o Who adheres to the practice model and who does not adhere? o Do those who adhere differ in any significant way from those that do not adhere? How do they differ? Is the difference based on something inherent in the worker such as intelligence, motivation, personality or general skills (e.g., interpersonal skills)? o Is the difference based on something about the situation such as supervisor support, caseload size, team support, or lack of resources in the agency or community?” o The organization may need to go back to Step 5 if there are problems at this step. o NH began the process evaluation immediately and is expanding it to assess fidelity to the model 35 Outcome Evaluation • Step 8 of GTO: Outcome Evaluation. o The agency must invest in an outcome evaluation to confirm the expectation of improved positive outcomes when the practice model is adhered to in each case with high levels of fidelity (setting a cut off of 70% adherence on the fidelity measure). o The outcome evaluation can answer “How well is the practice model working? o What is the impact of the practice model on worker retention? o What is the impact of the pm on child safety, permanency and well-being, family preservation and self sufficiency?” o NH is developing their outcome evaluation research design now and will begin to implement the study once fidelity is assessed. 36 Continuous Quality Improvement • Step 9 of GTO: Continuous Quality Improvement o Process and outcome evaluation, along with the CQI process of case reviews, can help the agency engage in continuous improvement of the model (e.g., Deming, 1986). o Stakeholders should be asking at this step, “How can the practice model be improved? o How can the implementation of and adherence to the practice model be improved?” o The results of the CQI can be used to answer these questions if the results are fed back to all stakeholders. NH is building in assessment of the PM into its ongoing CQI process to embed checking for fidelity and outcomes into the work. 37 Sustaining the Practice • Step 10 of GTO: Sustaining the practice. o Finally, the stakeholder committees must plan for sustainability, particularly in light of the fact that child welfare agency leaders turn over on average every two years. o If the practice model and its execution are successful, how will the initiative, and use of the practice model be sustained? o Good measurement at steps 7, 8 and 9 help to ensure sustainability o Engagement of other stakeholders imperative 38 Applying the GTO Model in New Hampshire 39 “This is not a new initiative… it will be our way of life” Maggie Bishop, NH DCYF Director May 2009 40 Assessing Needs and Resources: Steps to Change • 2009: Child Protective Services Supervisors recognized the need for a “model of practice” • 2009: Agency dialogue with Juvenile Justice “partners” expanded • 2009: Child and Family Services Plan started a vision • 2010: CFSR Statewide Assessment gave us critical insight • 2010: NCIC established sustained implementation projects= support/expertise available • 2010: CFSR Outcomes gave us the critical data and NOW the PIP=PM 41 http://cbexpress.acf.hhs.gov/index.cfm?event=website.viewPrinterFriendlyArticle&articleID=3265 42 New Hampshire DCYF/DJJS Practice Model Design & Implementation Project Logic Model Strategies Improve the quality and consistency of child welfare practice through the articulation and implementation of a practice model. Activities Establish a Practice Model Design Team, comprised of DCYF frontline staff, to create the practice model. Collect information and research about case practice approaches to inform Design Team’s work. Seek input from district office staff to refine practice model. Vision Our Practice Model will enhance the quality and effectiveness of child welfare throughout the State of New Hampshire by establishing a shared vision, consistency in practice and policy statewide, standardization of permanency practices and improvement of the accountability of those carrying out child welfare services across the state. Strengthen DCYF’s family engagement practice, family engagement in decisionmaking and service utilization Implement training & coaching program for all district office staff and supervisors as well as central office staff and managers. Develop and implement a Communications Plan. Obtain input and support from parents, youth, and stakeholder groups statewide throughout the design and implementation process. Modify organizational structures (policy, training, quality assurance, reporting etc) to support implementation and longterm sustainability of the practice model. Strengthen DJJS’ permanency practice. Identify sources of input and the DCYF managers who will obtain it. Identify key points for sharing drafts for feedback and clear pathways for providing and using input. Ensure staff from key organizational functions attend Design Team meetings to listen for implications for organizational change. Develop and test draft policies, reports, curricula with the Design Team. Engage youth and parent as codevelopers of policies. Develop a strategy for engaging DJJS staff in developing and implementing a permanency practice. Develop a Practice Model Design Team for DJJS Outputs Practice Model Developed by Design Team. Beliefs, Guiding Principles and Strategies articulated to all DCYF and DJJS Staff. Revised policies are implemented across DCYF and DJJS to reflect the Practice Model. BQI measures and reports are revised and distributed. Consistent permanency practices and a consistent family engagement model will be developed/adopted by DCYF and DJJS. Training curricula revised or developed to train all staff on the Practice Model. DCYF and DJJS staff and supervisors trained in the Practice Model. Focus groups utilized to gather feedback from all DCYF and DJJS stakeholders. Providers trained in the Practice Model. DJJS determined how Practice Model will be implemented with a focus on permanency. DJJS Design Team coordinate with original Design Team to ensure that New Hampshire has one consistent Practice Model. Consistent Training and Policies on Documentation will be implemented throughout DJJS. Outcomes The Practice Model is implemented consistently by DCYF and DJJS in all district offices. DCYF and DJJS Staff and Supervisors are proficient with Practice Model tools & approaches. Permanency Practices will be standardized across DCYF and DJJS. DCYF’s and DJJS’s Community stakeholders understand and support NH’s Practice Model. DCYF and DJJS use a variety of methods to continually assess and improve consistency of practice, effectiveness of family engagement strategies, and professional development. DCYF and DJJS organizational structures, policies and procedures are aligned to support the Practice Model’s sustainability. Improvement in outcomes related to effective child welfare practice (e.g. all children/youth have permanency plans, lower re-entry rates, higher reunification rates, reduced average length of stay in foster care, fewer average number of foster care placements, increased family engagement, improved outcomes on family satisfaction surveys, proper youth supervision will be achieved via Supervision Matrix (DJJS)). DJJS staff have skills & knowledge to engage families and implement effective permanency plans. DJJS’s utilization of the Practice Model’s family engagement strategies will decrease recidivism and re-entry and increase 43 permanency. Cross-Functional Project Teams Communication Team Members & roles defined Evaluation Team Policy Team Training Workgroup Sustainability linkages identified from the beginning Project Team Design Team 44 Staff from across the agencies Application and selection Monthly works sessions and homework in between Commitment to a decisionmaking process “Spread” leader Sustained engagement Youth and parent team members 45 46 47 48 Step 5: Assessing Organizational Capacities in NH • “Leadership” – authorized change - and asked for it to be owned at all levels! – Everyone is a potential leader of change – Everyone needs to be prepared to envision change and understand their role – Set expectations – Explored Challenges to change Design Team application and selection process Design Team members responsible for local facilitation of change Project Team members assigned areas of responsibility for change, i.e. Communication Team, WorkForce Development Committee, Organizational Learning and Training Team, Evaluation Team Supervisors – Supervisor Training “Organizational Readiness” Survey All staff “Readiness for Change” training 49 50 Transparency Feedback loops More is better Use varying approaches Go to the people Demonstrate passion! Youth, parents and staff tell the story best! Partnerships are critical to success 51 PIP = PM Crazy!! Dedicated agency staff time Project Consultants Combined agency and NCIC funding Long term view of sustainability drives agency PRACTICE 52 Exploration & Installation Leadership Cross-Functional Project Team Communication Resources Implementation Leadership Communication Cross-Functional Team Resources Coaching Sustainability Implementation plus Sustained Coaching, Communication & “Ownership” Culture & Climate Monitoring, Support & Resources Frequent Monitoring and Evaluation 53 References • For references, see the document upon which this talk is based: Barbee, A. P., Christensen, D., Antle, B., Wandersman, A. & Cahn, K.(2011). Successful adoption and implementation of a comprehensive casework practice model in a public child welfare agency: Application of the Getting to Outcomes (GTO) model. Children and Youth Services Review, 33, 622-633. 54 Contact Information Anita P. Barbee, MSSW, Ph.D. Professor, Kent School of Social Work University of Louisville Louisville, KY 40292 anita.barbee@louisville.edu Christine Tappan, MSW, CAGS Administrator, DCYF/DJJS Bureau of Organizational Learning & Quality Improvement Christine.Tappan@dhhs.state.nh.us 55