MatesPreliminaryPropertiesSS11

advertisement

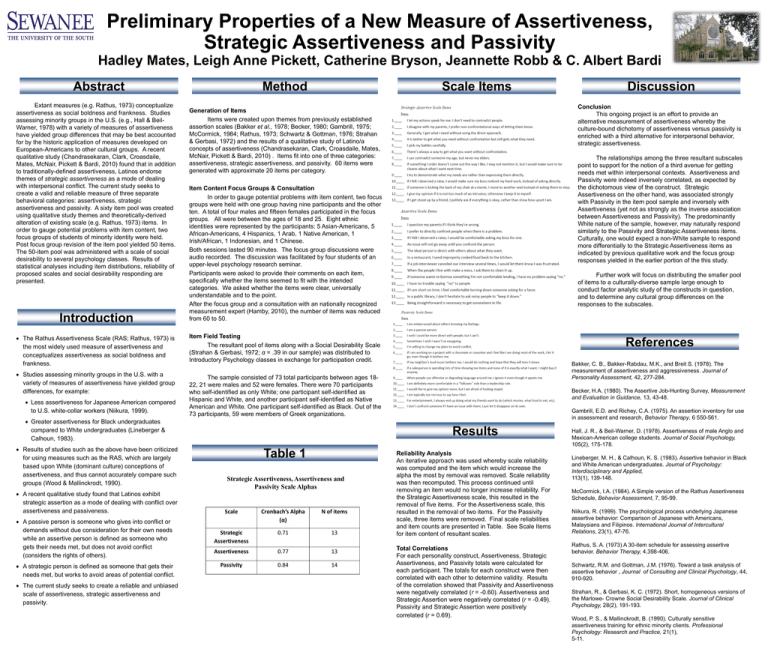

Preliminary Properties of a New Measure of Assertiveness, Strategic Assertiveness and Passivity Hadley Mates, Leigh Anne Pickett, Catherine Bryson, Jeannette Robb & C. Albert Bardi Abstract Extant measures (e.g. Rathus, 1973) conceptualize assertiveness as social boldness and frankness. Studies assessing minority groups in the U.S. (e.g., Hall & BeilWarner, 1978) with a variety of measures of assertiveness have yielded group differences that may be best accounted for by the historic application of measures developed on European-Americans to other cultural groups. A recent qualitative study (Chandrasekaran, Clark, Croasdaile, Mates, McNair, Pickett & Bardi, 2010) found that in addition to traditionally-defined assertiveness, Latinos endorse themes of strategic assertiveness as a mode of dealing with interpersonal conflict. The current study seeks to create a valid and reliable measure of three separate behavioral categories: assertiveness, strategic assertiveness and passivity. A sixty item pool was created using qualitative study themes and theoretically-derived alteration of existing scale (e.g. Rathus, 1973) items. In order to gauge potential problems with item content, two focus groups of students of minority identity were held. Post focus group revision of the item pool yielded 50 items. The 50-item pool was administered with a scale of social desirability to several psychology classes. Results of statistical analyses including item distributions, reliability of proposed scales and social desirability responding are presented. Introduction The Rathus Assertiveness Scale (RAS; Rathus, 1973) is the most widely used measure of assertiveness and conceptualizes assertiveness as social boldness and frankness. Studies assessing minority groups in the U.S. with a variety of measures of assertiveness have yielded group differences, for example: Less assertiveness for Japanese American compared to U.S. white-collar workers (Niikura, 1999). Method Scale Items Results of studies such as the above have been criticized for using measures such as the RAS, which are largely based upon White (dominant culture) conceptions of assertiveness, and thus cannot accurately compare such groups (Wood & Mallinckrodt, 1990). A recent qualitative study found that Latinos exhibit strategic assertion as a mode of dealing with conflict over assertiveness and passiveness. A passive person is someone who gives into conflict or demands without due consideration for their own needs while an assertive person is defined as someone who gets their needs met, but does not avoid conflict (considers the rights of others). A strategic person is defined as someone that gets their needs met, but works to avoid areas of potential conflict. The current study seeks to create a reliable and unbiased scale of assertiveness, strategic assertiveness and passivity. Conclusion This ongoing project is an effort to provide an alternative measurement of assertiveness whereby the culture-bound dichotomy of assertiveness versus passivity is enriched with a third alternative for interpersonal behavior, strategic assertiveness. Generation of Items Items were created upon themes from previously established assertion scales (Bakker et al., 1978; Becker, 1980; Gambrill, 1975; McCormick, 1984; Rathus, 1973; Schwartz & Gottman, 1976; Strahan & Gerbasi, 1972) and the results of a qualitative study of Latino/a concepts of assertiveness (Chandrasekaran, Clark, Croasdaile, Mates, McNair, Pickett & Bardi, 2010) . Items fit into one of three categories: assertiveness, strategic assertiveness, and passivity. 60 items were generated with approximate 20 items per category. The relationships among the three resultant subscales point to support for the notion of a third avenue for getting needs met within interpersonal contexts. Assertiveness and Passivity were indeed inversely correlated, as expected by the dichotomous view of the construct. Strategic Assertiveness on the other hand, was associated strongly with Passivity in the item pool sample and inversely with Assertiveness (yet not as strongly as the inverse association between Assertiveness and Passivity). The predominantly White nature of the sample, however, may naturally respond similarly to the Passivity and Strategic Assertiveness items. Culturally, one would expect a non-White sample to respond more differentially to the Strategic Assertiveness items as indicated by previous qualitative work and the focus group responses yielded in the earlier portion of the this study. Item Content Focus Groups & Consultation In order to gauge potential problems with item content, two focus groups were held with one group having nine participants and the other ten. A total of four males and fifteen females participated in the focus groups. All were between the ages of 18 and 25. Eight ethnic identities were represented by the participants: 5 Asian-Americans, 5 African-Americans, 4 Hispanics, 1 Arab, 1 Native American, 1 Irish/African, 1 Indonesian, and 1 Chinese. Both sessions lasted 90 minutes. The focus group discussions were audio recorded. The discussion was facilitated by four students of an upper-level psychology research seminar. Participants were asked to provide their comments on each item, specifically whether the items seemed to fit with the intended categories. We asked whether the items were clear, universally understandable and to the point. After the focus group and a consultation with an nationally recognized measurement expert (Hamby, 2010), the number of items was reduced from 60 to 50. Further work will focus on distributing the smaller pool of items to a culturally-diverse sample large enough to conduct factor analytic study of the constructs in question, and to determine any cultural group differences on the responses to the subscales. Item Field Testing The resultant pool of items along with a Social Desirability Scale (Strahan & Gerbasi, 1972; α = .39 in our sample) was distributed to Introductory Psychology classes in exchange for participation credit. References Bakker, C. B., Bakker-Rabdau, M.K., and Breit S. (1978). The measurement of assertiveness and aggressiveness. Journal of Personality Assessment, 42, 277-284. The sample consisted of 73 total participants between ages 1822, 21 were males and 52 were females. There were 70 participants who self-identified as only White; one participant self-identified as Hispanic and White, and another participant self-identified as Native American and White. One participant self-identified as Black. Out of the 73 participants, 59 were members of Greek organizations. Greater assertiveness for Black undergraduates compared to White undergraduates (Lineberger & Calhoun, 1983). Becker, H.A. (1980). The Assertive Job-Hunting Survey, Measurement and Evaluation in Guidance, 13, 43-48. Gambrill, E.D. and Richey, C.A. (1975). An assertion inventory for use in assessment and research, Behavior Therapy, 6 550-561. Results Table 1 Strategic Assertiveness, Assertiveness and Passivity Scale Alphas Scale Cronbach’s Alpha (α) N of items Strategic Assertiveness 0.71 13 Assertiveness 0.77 13 Passivity 0.84 14 Discussion Reliability Analysis An iterative approach was used whereby scale reliability was computed and the item which would increase the alpha the most by removal was removed. Scale reliability was then recomputed. This process continued until removing an item would no longer increase reliability. For the Strategic Assertiveness scale, this resulted in the removal of five items. For the Assertiveness scale, this resulted in the removal of two items. For the Passivity scale, three items were removed. Final scale reliabilities and item counts are presented in Table. See Scale Items for item content of resultant scales. Total Correlations For each personality construct, Assertiveness, Strategic Assertiveness, and Passivity totals were calculated for each participant. The totals for each construct were then correlated with each other to determine validity. Results of the correlation showed that Passivity and Assertiveness were negatively correlated (r = -0.60). Assertiveness and Strategic Assertion were negatively correlated (r = -0.49). Passivity and Strategic Assertion were positively correlated (r = 0.69). Hall, J. R., & Beil-Warner, D. (1978). Assertiveness of male Anglo and Mexican-American college students. Journal of Social Psychology, 105(2), 175-178. Lineberger, M. H., & Calhoun, K. S. (1983). Assertive behavior in Black and White American undergraduates. Journal of Psychology: Interdisciplinary and Applied, 113(1), 139-148. McCormick, I.A. (1984). A Simple version of the Rathus Assertiveness Schedule, Behavior Assessment, 7, 95-99. Niikura, R. (1999). The psychological process underlying Japanese assertive behavior: Comparison of Japanese with Americans, Malaysians and Filipinos. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 23(1), 47-76. Rathus, S. A. (1973) A 30-item schedule for assessing assertive behavior. Behavior Therapy, 4,398-406. Schwartz, R.M. and Gottman, J.M. (1976). Toward a task analysis of assertive behavior , Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 44, 910-920. Strahan, R., & Gerbasi, K. C. (1972). Short, homogeneous versions of the Marlowe- Crowne Social Desirability Scale. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 28(2), 191-193. Wood, P. S., & Mallinckrodt, B. (1990). Culturally sensitive assertiveness training for ethnic minority clients. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 21(1), 5-11.