Group Skills

A one-day primer by Steve Cottrell & Bob Neale

October 2010

Updated 07-06-13

Contacts

SERENE.ME.UK/HELPERS/

SERENE.ME.UK/HELPERS

#SERENITYPROGRAM

#SERENITYPROGRAM

FACEBOOK.COM/SERENITY.PROGRAMME

SERENITY.PROGRAMME

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License.

2

Aims & Objectives

Aims

•

To enhance the skills & knowledge of participants relevant to group leadership

Objectives – for participants:

•

To review their skills & knowledge relating to group leadership

•

To describe a classification of different types of groups

•

To develop an understanding of models of group development

•

To develop an understanding of constructive leadership behaviours

3

Introductions

Introductions

•

Who am I?

•

What’s my experience of running groups

•

What I’d like to get from today

4

Why might we run groups?

•

Advantages of groups

•

Disadvantages of groups

•

Why do we often choose individual work by default?

5

What’s Needed for a Successful Group? [1 of 3]

•

Types of groups

•

Optimal group size

•

Composition

•

Preparation – and what the leader needs for their well-being

•

Level of functioning

•

Recruitment criteria (inclusion and exclusion)

•

Pre-group assessment

•

Environment

•

Times

•

Optimal length of sessions and number of sessions

6

What’s Needed for a Successful Group? [2 of 3]

•

Types of groups

– open / closed / slow – open

– led / leaderless

– structured / unstructured

•

Optimal group size

– managing the periphery / managing intensity / managing difference

•

Composition

– heterogeneous / homogeneous

– gender / race / age distribution

7

What’s Needed for a Successful Group? [3 of 3]

•

Preparation – and what the leader needs for their well-being

•

Level of functioning

•

Recruitment criteria (inclusion and exclusion)

•

Pre-group assessment

•

Environment

•

Times

•

Optimal length of sessions and number of sessions

8

Individuals and the Group

•

Helping people learn in groups

•

Group members and their roles

•

Learning styles – Honey & Mumford

9

Three Functions … (Benne and Sheats)

Group members behaviour can be understood in three ways –

1. Maintenance roles – group building roles concerned with group processes and

functions

2. Task roles – concerned with completing the group task

3. Individual roles – not related to the above (may be self-interested and possibly

distracting from work group tasks)

10

Maintenance Roles

•

Encourager – positive influence on group

•

Harmoniser – make or keep peace

•

Compromiser – minimises conflict

•

Gatekeeper – determines level of acceptance of difference

•

Follower – audience

•

Rule maker – sets standards for what's acceptable

•

Problem solver – allows group to address problems and move on

11

Task Roles

•

Leader – sets direction / emotional climate

•

Questioner – to clarify issues

•

Facilitator – to keep focus

•

Summariser – to ‘take stock’

•

Evaluator – to assess progress and performance

•

Initiator – to begin / change direction

Benne, KD & Sheats, PJ (1948) Functional roles and group members (J. Soc. Issue 4)

12

Individual Roles

•

Victim – To deflect responsibility form self

•

Monopoliser – To actively seek control by incessant talking

•

Seducer – to maintain distance and gain attention

•

Mute – To passively seek control through silence

•

Complainer – to ventilate anger and discourage positive work

•

Truant / latecomer – to invalidate significance of group

•

Moralist - to serve as judge of right and wrong

Note negative emphasis – an opportunity for reframing!

13

Role are not Fixed

•

Roles are not fixed, though people tend to have a preferred role

•

The group may influence people to adopt roles different from their usual

preferred choice (‘role suction’)

14

Learning Styles

•

Peter Honey and Alan Mumford developed their ‘learning styles’ system as a

variation on the ‘Kolb model’ while working on a project for the Chloride

Corporation in the 1970's. Over the years we develop learning ‘habits’ that help us

benefit more from some experiences than from others

•

Since we’re probably unaware of our preferred learning style, this questionnaire

will help you pinpoint your learning preferences so that you’re in a better position

to select learning experiences that suit your style, and design learning experiences

for a wider range of people. Note though widely used, there’s not a great deal of

empirical evidence for this approach!

15

Learning Style Questionnaire

•

There is no time limit to this questionnaire, It will probably take you about 15

minutes. There are no ‘right’ or ‘wrong’ answers. If you agree more than you

disagree with a statement, put a tick by it . If you disagree more than you agree

with a statement, put a cross by it.

•

Be sure to mark each item with either a tick or a cross

Based on the work of Honey, P. and Mumford, A. ‘Using your learning styles’ 1986

16

Activists

•

Are ‘here and now', gregarious, seek challenge and immediate experience, are

open-minded, can become bored with lengthy implementation. Activists like to be

involved in new experiences and are enthusiastic about new ideas. Activists enjoy

doing things and might act first and consider the implications afterwards. They are

unlikely to prepare much for a learning experience or to review their learning

much afterwards.

17

Reflectors

•

Reflectors ‘stand back', gather data, ponder and analyse, they delay reaching

conclusions, listen before speaking, and are thoughtful. Reflectors like to view a

situation from different perspectives. They like to collect data, review and think

carefully before coming to any conclusions. Reflectors enjoy observing others and

will often listen to others views before offering their own.

18

Theorists

•

Theorists ‘think things through’ in logical steps; they assimilate disparate facts into

coherent theories, are rationally objective and reject subjectivity and flippancy.

Theorists like to adapt and integrate observations into complex and logically

sound theories. They think problems through step-by-step. They tend to be

perfectionists who like to fit things into a rational scheme.

19

Pragmatists

•

Pragmatists seek and try out new ideas, are practical, enjoy problem solving and

decision-making. Pragmatists are eager to try things out in practice. They like

concepts that can be applied to their job. They tend to be impatient with lengthy

discussions and are practical and down to earth.

20

LSQ

21

Contents

•

Group decision making - polarization

•

Obedience and conformity

•

Bystander apathy

•

Groupthink

•

Social conformity

•

Social facilitation and social loafing

•

Models of group development – Tuckman

•

Constructive and destructive leadership behaviours

22

Group Polarization

•

The ‘risky shift’ is the tendency for decisions taken by a group after discussion to

display more experimentation, be less conservative and be more risky than those

made by individuals acting alone prior to any discussion

•

In 1970, Myers and Bishop demonstrated this effect by arranging students into

groups to discuss issues of race. Groups of prejudiced students were found to be

become even more prejudiced, while unprejudiced students became even less

prejudiced

•

Thus, before we can predict how the discussion will polarize the group, we must

know the initial opinions of the members!

Discussion effects on racial attitudes. Myers, D. G., & Bishop, G. D. (1970). Science, 169, 778-779.

23

Social Influence and Conformity

•

Social Influence:

– How individual behavior is influenced by other people and groups

•

Conformity:

– Tendency to change our behaviour / beliefs / perceptions in ways that

are consistent with group norms

•

Norms:

– Accepted ways of thinking,

feeling, behaving

24

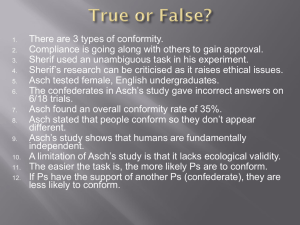

Obedience and Conformity

Harvard psychologist Herbert Kelman (1958) identified three major types of social

influence:

1. Compliance - public conformity, while keeping one's own beliefs private

2. Identification - conforming to someone who is liked and respected, such as a

celebrity or a favoured relative

3. Internalization - acceptance of the belief or behaviour and conforming both

publicly and privately

Kelman, H. (1958). Compliance, identification, and internalization: three processes of attitude change.

Journal of Conflict Resolution, 1, 51-60.

25

Solomon Asch & Conformity [1 of 4]

•

The Asch conformity experiments, published in the

1950's, demonstrated the power of conformity in

groups

•

Students were asked to participate in a ‘vision test’,

all but one of the participants were confederates the study was really about how the remaining

student would react to the confederates' behaviour

26

Solomon Asch & Conformity [2 of 4]

In a control group, with no pressure to conform, only 1 subject out of 35 ever gave an

incorrect answer. However, when surrounded by individuals all voicing an incorrect answer,

participants provided incorrect responses on a high proportion of the questions (37%),

while 75% of the participants gave an incorrect answer to at least one question — 75% of

participants conformed to the erroneous majority view at least once

27

Solomon Asch & Conformity [3 of 4]

One confederate has virtually no influence, two confederates have only a small

influence. When three or more confederates are present, the tendency to

conform is relatively stable

Conformity responses %

•

40

20

0

0

2

4

6

8

10

Group Size

28

Solomon Asch & Conformity [4 of 4]

•

When confederates were not unanimous, even if only 1 voiced a different opinion,

participants were much more likely to resist the urge to conform than when the

confederates all agreed. This finding holds whether or not the dissenting

confederate gives the correct answer. As long as the dissenting confederate gives

an answer that is different from the majority, participants are more likely to give

the correct answer

•

The subjects of these studies attributed their performance to their own

misjudgement and ‘poor eyesight’ – they remained unaware of the influence of

the majority, supporting the notion that we may have little insight into the true

influences on our behaviour, with our explanations sometimes being ‘post-hoc’

rationalisations

29

Milgram & Obedience

•

Stanley Milgram (1933 – 1984) - 65% of participants gave the final 450-volt shock,

no participant refused to administer shocks before the 300-volt level

•

In Milgram's ‘Experiment 18: A Peer Administers Shocks’, 37 out of 40 participants

administered the full range of shocks up to 450 volts, the highest obedience rate.

In this variation, the actual subject didn’t pull the shock lever;

instead he merely conveyed information to the peer

(a confederate) who pulled the lever.

Thomas Blass examined Milgram studies and

replications during a 25-year period …

30

Do Milgram’s findings apply today?

•

Thomas Blass examined Milgram studies and replications during a 25-year period

from 1961 to 1985 – he correlated year of publication with the amount of

obedience - no significant correlation found

•

Who are more obedient - men or women? Milgram found an identical rate of

obedience in both groups - 65% - although obedient women consistently reported

more stress than men. There are about a dozen replications of the obedience

experiment world-wide which had male and female subjects. All of them, with one

exception found no sex differences

31

Bystanding

•

The bystander effect (also known as bystander apathy) is a psychological

phenomenon in which someone is less likely to intervene in a situation when

other people are present and able to help than when he or she is alone

•

Kitty Genovese was a New York City woman who, in 1964, was stabbed to death

near her home in Queens, New York

32

Kitty Genovese

•

Genovese parked 100 feet from her apartment's door, she was approached by

Winston Moseley who stabbed her twice in the back. She screamed "Oh my god he

stabbed me! Help me!" she was heard by several neighbours; Moseley stabbed her

several more times. While she lay dying, he sexually assaulted her

•

He stole about $49 from her. The attack lasted about 30 minutes. During his final

attack a neighbour opened the door and watched the attack without doing anything

to intervene

•

A few minutes after the final attack, a witness, Karl Ross, called the police. Genovese

died on her way to hospital. Later investigation revealed that approximately a dozen

individuals nearby had heard or seen portions of the attack

33

Groupthink

Groupthink – occurs more often when groups are under pressure to make

decisions, where need for unanimity supersedes rational, individual thought

Social psychologist Clark McCauley identified three conditions under which

groupthink occurs:

1. Directive leadership

2. Homogeneity of members' social background and ideology

3. Isolation of the group from outside sources of information and analysis

34

Irving Janis’ 8 ‘symptoms’ of groupthink

•

Illusions of invulnerability creating excessive optimism and encouraging risk taking

•

Rationalising warnings that might challenge the group's assumptions

•

Unquestioned belief in the morality of the group, causing members to ignore the

consequences of their actions

•

Stereotyping those who are oppose the group as weak, evil or stupid

•

Direct pressure to conform placed on any member who questions the group,

couched in terms of ‘disloyalty’

•

Self censorship of ideas that deviate from the apparent group consensus

•

Illusions of unanimity among group members, silence is viewed as agreement

•

Mindguards — self-appointed members who shield the group from opposing

information

35

Helping to prevent groupthink

•

Leaders should assign each member the role of ‘critical evaluator’ - this allows

each member to freely air objections and doubts

•

‘Higher-ups’ should not express an opinion when assigning a task to a group

•

The organisation should set up several independent groups, working on the same

problem

•

All effective alternatives should be examined

•

Each member should discuss the group's ideas with trusted people outside of the

group

•

The group should invite outside experts into meetings - group members should be

allowed to discuss with and question the outside experts

•

At least one group member should be assigned the role of ‘Devil's advocate’ - this

should be a different person for each meeting

36

Social Facilitation

•

Triplett (1898)

– Noticed cyclists performed better when riding with others

– Study with children performing simple task either alone or with others

– Results:

Children performed better when in the presence of others compared to when

alone

37

Social Facilitation after Zajonc

•

Dominant response:

– Well-learned or instinctive behaviors that the organism has practiced and is

primed to perform

•

Non-dominant response:

– Novel, complicated, or untried behaviors that the organism has never

performed (or performed infrequently)

•

The presence of others increases our tendency to perform dominant responses

‘Zajonc’ is pronounced ‘ZI-yence’

38

Research Examples

•

Cockroach study (Zajonc et al. 1969) :

– Not limited to humans!

– Cockroaches performed simple or difficult task

– [Runway or maze]

– Measured speed when alone or with fellow roaches present

– Presence of other roaches facilitated performance on easy task and

hampered it on difficult task

39

‘Cockroach’ Study

Seconds

40

Social Facilitation Effect

Performance

Improves

Know the task well

Perform task in

presence of

audience

Do not know the task well

Performance

Declines

41

Social Loafing

•

Maximilien Ringelmann (1861-1931) - people alone and in groups pull on a rope,

the sum of the individual pulls did not equal the total of the group pulls. Three

people pulled at only 2.5 times the average individual performance, and 8 pulled

at less than a fourfold performance. The group result was much less than the sum

of individual efforts.

•

Social loafing

– Members work below their potential when in a group

–

Ingham, A.G., Levinger, G., Graves, J. and Peckham, V. (1974). The Ringelmann Effect: Studies of

group size and group performance. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 10, 371-84

42

Research Example

•

Shouting experiment [1]

– People separated into rooms with headphones

– Led to believe they were shouting alone or with others

– Results:

• Groups of 2 shouted at 66% capacity

• Groups of 6 at 36% capacity

•

People exhibit a sizable decrease in individual

effort when performing in groups

[1] Latane, B., Williams, K., & Harkins, S. (1979). Many hands make light the work: The causes and consequences

of social loafing. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology, 37(6), 822-832 pared to alone

43

Summary

Groups may influence people:

•

To make more extreme decisions - ‘risky’ or ‘cautious’ shift

•

To find it difficult to disagree with the majority and doubt oneself - Asch

•

To ‘deindividuate’ (to all think alike) – groupthink

•

To become passive – bystanding

•

To become obedient / conform – Milgram, Zimbardo

•

To diffuse responsibility – someone else will wash the cups!

•

To contribute less in groups – social loafing

•

To perform better / worse on familiar / unfamiliar tasks – audience effects

44

Models of Group Development

•

‘Stages’ are not discrete or distinctly separate phases, and

are often most recognisable in closed task groups

•

Groups ‘regress’ when new members introduced – need to

re-work identity, rules and values

45

Tuckman

•

Dr Bruce Tuckman published his ‘Forming, Storming, Norming, Performing’ model

in 1965

•

He refined his theory around 1975 and added a fifth stage to the model - he called

it ‘Adjourning’, also referred to as ‘Deforming’ and ‘Mourning’

46

Individual and Group Issues

Forming

Individual

Issues

Group

Issues

Storming

Norming

Performing

“How do I fit

in?”

“What’s my

role here?”

“What do the

others expect

me to do?”

“How can I best

perform my

role?”

“Why are we

here?”

“Why are we

fighting over

who’s in

charge and who

does what?”

“Can we agree

on roles and

work as a

team?”

“Can we do the

job properly?”

47

Concerns at this Stage - Forming

•

Time structuring through rituals and pastimes

•

Fantasies about ground rules, expectations about behaviour based on past

experience

•

Preoccupation and dependence on leader

•

Orientation, through testing and dependence (Tuckman)

48

Leadership Tasks - Forming

•

Physical and psychological boundaries which are secure and stable – creating of an

‘epistemic space’, an ‘alchemical container’

•

External boundary is a function of the internal boundary, which in turn is a

function of leadership potency

•

Clarify ‘who’s in, who’s out, and who’s in charge’

•

Clarify which decisions are members to make, and which are leaders alone

•

‘In groups with a weak internal boundary, the external boundary is seen as a fence

containing members in an unsafe space’

Gurowitz, 1975, p.184

49

Destructive Behaviour - Forming

•

Tyranny of structurelessness

•

Excessive anxiety

•

Hidden sadism

•

Role confusion

•

Not managing nurturing, control, seduction, aggression

•

Overly task-oriented

•

Abdication of leadership role

•

Focus on few, neglecting the majority

50

Constructive Behaviour - Forming

•

Clear time structure and boundaries

•

Clarity and potency

•

Optimal anxiety, not incapacitation

•

Clear assumption of leadership

•

Clarity of group task

•

Allowing ‘getting to know’ process

•

Practical information – toilets, breaks etc.

•

Foster participation and collaboration

51

Tuckman’s ‘Storming’ Stage

“The second point in the sequence is characterised by conflict and

polarisation around interpersonal issues with concomitant emotional

responding in the task sphere. These behaviours serve as resistance to

group influence and task requirements, and may be labelled as storming”

Tuckman, 1965, p 396

52

Concerns at this Stage - Storming

•

The emotional response to task demands

•

Conflict with / rebellion against leader

•

Testing leaders effectiveness

•

Conflict between members may mask unsatisfactory management of

storming

53

Constructive Leadership - Storming

•

Surviving verbal attack – without punishing, withdrawing, collapsing or becoming

apologetic

•

Not seeking support from group - seeking support elsewhere

•

Giving self ‘benefit of doubt’

•

Not too frightening, not too fragile

•

Listening to feedback

•

Not giving in to threats / emotional blackmail

•

Validating feelings without necessarily agreeing

•

Transparency around decision making

54

Destructive Leadership - Storming

•

Deflects or denies aggression – smoothes over conflict

•

Interprets anger as pathology to invalidate / patronise members

•

Appearing fragile, going ‘off sick’, appearing hurt

•

Avoids sanctions or uses unfair sanctions

55

Norming

“Resistance is overcome in the third stage in which in-group feelings and

cohesiveness develop, new standards evolve and new roles are adopted. In the task

realm, intimate personal opinions are expressed, thus we have the stage of Norming.”

(Tuckman, 1965 p 396)

56

Concerns at this Stage - Norming

•

Value–congruent psychological communication

•

Importance of ‘throw-away’ lines and management of the periphery

•

Resisting premature norming to maintain flexibility rather than the

‘oppression of certainty’

57

Destructive Leadership - Norming

•

Reinforcing rigidity

•

Setting rules instead of norms

•

Discounting group personality and culture

•

Failing to manage ‘rogue elephants’

58

Constructive Leadership - Norming

•

Encouraging discussion of norms

•

Not accepting there is only ‘one right way’

•

Allowing groups personality to develop

•

Focus on culture building rather than adoption of unconsidered ‘rules’

•

Transparency around leaders values and ethics

59

Performing

“Roles become flexible and functional and group energy is channelled into the task.

Structural issues have been resolved, and structure can now become supportive of

task performance. This stage can be labelled as performing.”

(Tuckman, 1965 p 396)

60

Concerns at this Stage - Performing

•

Individuals relinquish own needs in support of cohesion and task performance

•

The ‘leader is surrounded by leaders’

•

Not always happy, but learning!

•

Leader enjoyment

•

Focus on fun, work, validating spontaneity, autonomy, immediacy, authenticity,

feelings , skills, knowledge and expertise

61

Destructive Leadership - Performing

•

‘I know better’ stance

•

Hogs credit

•

Clings to leadership

•

Over-focus on task

62

Constructive Leadership - Performing

•

Sits back and relaxes

•

Allows others to lead

•

Becomes mutual participant

•

Emphasises own learning

•

Keen to experiment

•

Focus on group pleasure as well as task

•

Permission to work and have fun

•

Listens and validates

63

Adjourning

Four important tasks:

•

To accept the reality of the loss

•

To experience the pain of grief

•

To adjust to a changed environment

•

To withdraw emotional energy and re-invest in another relationship

(Worden, 1983)

64

Destructive Leadership - Adjourning

•

Being prescriptive about mourning

•

Colluding with group denial

•

‘Cats goodbyes’

•

Sickly prescription ‘let’s all hug’

•

Behaving defensively

•

Foreshortening reminiscing

•

Not allowing afterglow of satisfaction

65

Constructive Leadership - Adjourning

•

Many ways to grieve – permission giving

•

Predicting difference

•

Protecting time for grief

•

Honesty and non-defensiveness

•

Definite time for ending

•

Allowing a ritual

•

Allowing reminiscence

•

Gracious acceptance of recognition and appreciation

•

Allowing this ending to be used as a learning experience for future endings

66

Returning to ‘Why Groups?’ [1 of 2]

Irvin D. Yalom’s ‘Curative Factors’

•

Instillation of Hope - faith that the treatment mode can and will be effective

•

Universality - demonstration that we are not alone in our misery

•

Imparting of information - didactic instruction about mental health

•

Altruism - opportunity to rise out of oneself and help somebody else

•

Corrective recapitulation of primary family group - experiencing transference

relationships growing out of primary family experiences providing the opportunity to

relearn and clarify distortions

67

Returning to ‘Why Groups?’ [2 of 2]

•

Development of socializing techniques - social learning or development of

interpersonal skills

•

Imitative behavior - taking on the manner of group members who function more

adequately

•

Catharsis - opportunity for expression of strong affect

•

Existential factors - recognition of the basic features of existence through sharing with

others (e.g. ultimate aloneness, ultimate death, ultimate responsibility for our own

actions)

•

Direct Advice - receiving and giving suggestions for strategies for handling problems

•

Interpersonal learning - receiving feedback from others and experimenting with new

ways of relating

68

Conclusion

•

Small group feedback

•

What has been important / useful / interesting

•

What will you take away from today?

69

References

•

Berne, E., (1975) The structure and dynamics of organisations and groups. New York: Grove Press

•

Clarkson, P (1988) Group Imago and the Stages of Group Development: A Comparative Analysis of the Stages of the Group

Process. ITA News (1988, Spring) 20 pp. 4-16.

•

Foulkes, S. H. (1951). Concerning leadership in group-analytic psychotherapy. International Journal of Group Psychotherapy,

l, 319-329.

•

Gurowitz, E. (1975) Group boundaries and leadership potency. Transactional Analysis Journal, 5 (2) p 183 - 185

•

Lacoursiere, R. (1980) Life cycle of groups. New York: Human sciences press

•

The Theory and Practice of Group Psychotherapy, 4th Edition, Basic Books, 1995

•

Tuckman, B. W. (1965). Developmental sequences in small groups. Psychological Bulletin, 63, 384-399

•

Tuckman, B. W., & Jensen, M. A. C. (1977). Stages of small group development revisited. Group and Organizational Studies,

2, 419- 427

•

Worden, J. W. Grief Counselling and grief therapy. London: Tavistock Publications

70