Message Design Strategies to Promote Awareness and Action to

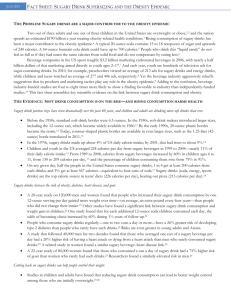

advertisement

Communicating Public Health: Message Design Strategies to Promote Awareness and Action to Address Social Determinants of Health Jeff Niederdeppe, Ph.D. Associate Professor Department of Communication Cornell University jdn56@cornell.edu Join the Conversation: #healthcomm P1 Collaborators • • • Sarah E. Gollust – University of Minnesota SPH Colleen L. Barry – Johns Hopkins SPH Michael A. Shapiro, Hye Kyung (Kay) Kim, Helen Lundell, Sungjong Roh – Cornell University Funding Support • • • RWJF Healthy Eating Research Program (69173, 68051) RWJF Health and Society Scholars Program RWJF Grant to University of Wisconsin Population Health Institute – Mobilizing Action Toward Community Health Presentation Outline • What are we trying to communicate, to whom? • • • What are we trying to change? What are we up against? Three lessons learned 1. Education and awareness may not be enough 2. Connect messages to broader values 3. Opposing messengers are a challenge • Some concluding thoughts Traditional Health Communication • Focus has largely been on changing individual behavior, BUT… • Behaviors and health outcomes are largely shaped by larger social, political, economic environments • Need different message strategies, may be at odds with a focus on individual behavior Features of Many Health Issues • Strong sense of personal responsibility for health in public opinion and discourse Public Opinion about Factors that Very Strongly Influence Health 100% 90% 80% 70% 60% 50% 40% 30% 20% 10% 0% Personal Health practices Affordable Health Care Has Health Insurance Income Education Where a Race/ethnicity Person Lives Source: Robert, S. A., & Booske, B. C. (2011). U.S. opinions on health determinants and social policy as health policy. American Journal of Public Health, 101, 1655-1663. Features of Many Health Issues • Strong sense of personal responsibility for health in public opinion and discourse • Powerful industries promoting health-harming products, incredible $ resources to fight regulation For Example… Features of Many Health Issues • Strong sense of personal responsibility for health in public opinion and discourse • Powerful industries promoting health-harming products, incredible $ resources to fight regulation • Wide body of evidence on the influence of the larger social, economic, physical, and built environment Ecological Model of Healthy Eating Features of Many Health Issues • Strong sense of personal responsibility for health in public opinion and discourse • Powerful industries promoting health-harming products, incredible $ resources to fight regulation • Wide body of evidence on the influence of the larger social, economic, physical, and built environment • Complex mechanisms linking these factors to health outcomes and behaviors Factors that Cause Obesity: A Systems View (105 variables) Who is the Target of the Message / Campaign? Public Opinion (persuade the opposition) Public Opinion (mobilize issue publics) Policymaker Action Policies To Create Healthy Environments Healthier Environments to Improve Health and Reduce Health Disparities What are the Targeted Outcomes for Effective Communication about Population Health? What are the Targeted Outcomes for Effective Communication about Population Health? 1. Increase awareness of health disparities 2. Increase belief that disparities are worth addressing 3. Heighten belief that societal forces and actors cause, and are responsible for, poor health and disparities 4. Promote support for policies with potential to improve social determinants and reduce disparities 5. Mobilize action to advocate for social change Lesson 1: Raising Awareness is Not Sufficient Lesson 1: Raising Awareness is Not Sufficient • Priming group differences Priming Group Differences • Public support for government intervention depends on type of group difference – Economic disparities: greatest support – Racial disparities: least support • Perceptions of the causes of group differences matter – Relates to underlying attitudes about causality, responsibility, and fairness – Behaviors vs. social structure vs. genetics Sources: Rigby et al. (2009); Lynch & Gollust (2010) Lesson 1: Raising Awareness is Not Sufficient • Priming group differences • Pre-existing awareness and values lead to “biased processing” Biased Processing of SDH Messages Level of Support for Non-Medical Diabetes Prevention Policies (higher values, more support) Proportion Agreeing "Diabetes Caused by Social and Economic Factors" 0.45 3.8 0.4 3.6 Democrats 0.35 3.4 Independents 0.3 3.2 Republicans 0.25 3 0.2 2.8 0.15 2.6 0.1 2.4 0.05 2.2 2 0 Control Social Determinants Experimental Causal Frame Viewed Source: Gollust, Lantz, Ubel; AJPH (2009) Control Social Determinants Experimental Causal Frame Viewed Biased Processing of SDH Messages • Focus group insight • Without concrete mechanisms for how SDH produce disparities, people fill in the blanks with preconceptions • In response to a chart showing the bivariate association between education and life expectancy: “Maybe somebody didn’t go on to school or even didn’t finish high school but they might have gotten a good education at home in terms of how to be a healthy person.” Source: Lundell, Niederdeppe, & Clarke, 2013 Lesson 2: Connect Messages to Larger Values Lesson 2: Connect Messages to Broader Values • Acknowledge personal responsibility – BUT… • Proceed with caution MALL EXPERIMENT Insights from Mall Experiment • Methods • 500 participants, 4 conditions, summer 2010 • Michele’s story – environmental and economic causes of obesity, neighborhood development as an effective solution Niederdeppe, J., Shapiro, M., Kim, H. K., Bartolo, D., & Porticella, N. (2013). Narrative persuasion, causality, complex integration and support for social policy. Health Communication, doi:10.1080/10410236.2012.761805. MALL EXPERIMENT Three groups were exposed to Michele’s story about (1) the causes of obesity and (2) neighborhood development as one solution MALL EXPERIMENT Insights from Mall Experiment • Methods • 500 participants, 4 conditions, summer 2010 • Research Question: • How strongly should a story emphasizing SDH as causes and solutions for obesity • Acknowledge personal responsibility • To increase complexity of thinking about obesity’s causes, and • Maximize support for obesity policies? MALL EXPERIMENT Example of Condition Differences • High Responsibility • • Moderate Responsibility • • Here, she feels comfortable getting out of the house and exercising outside – activities Michele sees as tremendously important for improving her health. This has helped Michele to develop healthier lifestyle habits. Here, she feels more comfortable getting out of the house and getting outside. This has helped Michele to have more options for improving her health – even though following through on them is a challenge. Low Responsibility • Here, she feels more comfortable getting out of the house, even if she’s not intending to exercise. MALL EXPERIMENT Condition Effects on Support for ObesityReducing Public Policies High 4.2 4.0 3.8 3.6 3.4 3.2 3.0 2.8 2.6 2.4 2.2 Liberals Mid Low Moderates Control Conservatives Niederdeppe, J., Shapiro, M., Kim, H. K., Bartolo, D., & Porticella, N. (2013). Narrative persuasion, causality, complex integration and support for social policy. Health Communication, doi:10.1080/10410236.2012.761805. MALL EXPERIMENT Condition Effects on Intentions to Engage in Diet and Exercise 4.2 4.0 3.8 3.6 3.4 3.2 3.0 2.8 2.6 2.4 2.2 High Normal Weight Mid Low Control Overweight or Obese Niederdeppe, J. et al. (2013). Effects of emphasizing environmental determinants of obesity on intentions to engage in diet and exercise behaviors. Preventing Chronic Disease, http://dx.doi.org/10.5888/pcd10.130163. … BUT Proceed with Caution • Personal narratives can shift emphasis to individual responsibility • Stories about individual children can increase blame to children for obesity • Policymakers counterargue individual narratives unless combined with broader statistics or a story told about the community Sources: Barry, Brescoll, Gollust (2013); Niederdeppe et al. (2014b) Lesson 2: Connect Messages to Broader Values • Acknowledge personal responsibility – BUT… • Proceed with caution • Identify novel values related to population health improvement to reach broader coalitions Identify novel values (1) Source: Gollust, Niederdeppe, Barry, 2013 Identify novel values (2) • Fairness and equal opportunity, not equal outcomes Source: Lynch and Gollust (2010) Lesson 3: Opposing Messages(-ers) are a Challenge Lesson 3: Opposing Messages(-ers) are a Challenge • It can be useful to anticipate and try to offset counter-arguments from opponents of social change NATIONAL EXPERIMENT How tackling opposing arguments can be useful • Content analysis of arguments used to support and oppose the tax in public discourse • Niederdeppe et al., AJPH, 2013 • Public opinion poll gauging response to discrete pro- and anti-tax arguments • Barry et al., AJPM, 2013 • In-depth interviews with SSB tax proponents and advocates in jurisdictions where taxes proposed • Jou et al., AJPH, 2014 NATIONAL EXPERIMENT Surveys to Identify Resonant Frames – Pro-Tax NATIONAL EXPERIMENT Surveys to Identify Resonant Frames – Anti-Tax NATIONAL EXPERIMENT Theoretical Rationale • Strongest pro-tax arguments focus on: • Largest driver of obesity (“softening the ground”) • Provides funds for childhood obesity prevention • Beverage industry outspends pro-tax advocates by a large margin; anti-tax arguments resonate strongly • Inoculation Theory • Protect from subsequent (persuasive) attack by highlighting source motives and countering weak arguments (“industry demonization”) NATIONAL EXPERIMENT National Randomized Experiment • Randomized experiment conducted from OctoberDecember, 2012 using the survey research firm GfK Group (Knowledge Networks) • 3,118 completed baseline survey and follow-up (sent 1-week later and completed within 2 weeks) NATIONAL EXPERIMENT Overview of Experimental Conditions Arm Approach Time Period 1 Time Period 2 Arm 1 Control condition No exposure No exposure Arm 2 Control condition No exposure Strong con-message 1 Strong pro-message 1 No exposure Strong pro-message 1 Strong con-message 1 Single message (not countered) Single message Arm 4 (countered at time 2) Arm 3 Arm 5 Multi-message Arm 6 Multi-message (w/repeat pro-message) Arm 7 Inoculation frame Arm 8 Inoculation frame (w/repeat pro-message) Strong pro-message 1, strong con-message 1 Strong pro-message 1, strong con-message 1 Inoculation (weak conmessage with refutation) Inoculation (weak conmessage with refutation) Strong con-message 2 Strong con-message 2, strong pro-message 2 Strong con-message 1 Strong con-message 1, strong pro-message 1 NATIONAL EXPERIMENT A Strong Pro-Tax Argument Supporters of a tax say that sugary drinks may be the single largest driver of obesity in the United States. More children are obese today than in previous generations. Rates of obesity have tripled among children and teens over the past 30 years. Children and teens drink twice as much soda and other sugary drinks as they did 30 years ago. Supporters of a tax say drinking a 20-oz soda is equivalent to eating 16 packets of sugar. That’s 240 empty calories in a single bottle. When people consume sugary drinks, they do not feel full, so they tend to eat more food. Children who drink sugary beverages also prefer foods with higher calories, leading to worse overall nutrition. NATIONAL EXPERIMENT A Strong Anti-Tax Argument Opponents of a tax say obesity is a matter of how many calories people consume, not where those calories come from. A tax on sugary drinks is arbitrary because it does not affect other unhealthy foods like donuts, cookies, and candy bars. Obesity is a complex problem that cannot be solved by focusing on just one small part of a person’s diet. Sugary drinks account for only 7 percent of calories in the average American's diet. Science shows that obesity is caused by an imbalance between the calories we consume through food and drinks and those we burn through daily activities and exercise. NATIONAL EXPERIMENT Inoculation Treatment Soda companies will try to convince you that a tax on sugary drinks is arbitrary because it does not affect foods like donuts, cookies, and candy bars. They will say that they are an unacceptable intrusion of government into people’s personal choices. They will call them “food taxes” to try to confuse people. But sugary drinks are not food – they have no nutritional value. In fact, research suggests that sugary drinks are the single largest driver of obesity in the United States. Nobody is telling anyone what to drink. But, by adding a few pennies to the price of a soda, many people will choose differently. NATIONAL EXPERIMENT Tackling opposing arguments can be useful… 5.50 No exposure Strong pro-, No anti- Strong pro-, Strong anti- Inoculation (Strong pro-) 5.25 5.00 4.75 * Denotes p<.05; **p<.01 vs. no exposure control * 4.50 ** 4.25 4.00 Scale Midpoint 3.75 3.50 3.25 3.00 * 2.75 2.50 2.25 2.00 Support for SSB Tax Policy SSB Companies Try to Get Kids to Drink SSBs NATIONAL EXPERIMENT … At Least in the Short-Term. 5.00 Baseline 4.75 Follow-Up 4.50 4.25 4.00 Scale Midpoint 3.75 3.50 3.25 3.00 2.75 2.50 2.25 2.00 No exp. t1, No exp. t2 Strong pro t1, No exp. t1, Strong pro t1, Both t1, No exp. t2 Strong con t2 Strong con t2 Strong con t2 Both t1, Both t2 Inoculation t1, Inoculation t1, Strong con t2 Both t2 NATIONAL EXPERIMENT … At Least in the Short-Term. 5.00 Baseline 4.75 Follow-Up 4.50 4.25 4.00 Scale Midpoint 3.75 3.50 3.25 3.00 2.75 2.50 2.25 2.00 No exp. t1, No exp. t2 Strong pro t1, No exp. t1, Strong pro t1, Both t1, No exp. t2 Strong con t2 Strong con t2 Strong con t2 Both t1, Both t2 Inoculation t1, Inoculation t1, Strong con t2 Both t2 Lesson 3: Opposing messages(-ers) are a challenge • It can be useful to anticipate and try to offset counter-arguments from opponents of social change • BUT… • Strategies to neutralize the opposition may not work across all social groups % difference from the no-exposure control group; †p<0.10; *p<0.05 from OLS regression Politically Polarizing Message Effects 20.0% 15.0% 15.1%* 14.0%† 12.3%† 10.0% Significant interaction term (β=-0.83, p=0.02) for Republican x inoculation 5.0% 2.9% Republicans Democrats 0.0% Independents -5.0% -5.3% -4.5% -8.0%-7.6% -10.0% -12.3% -15.0% Strong pro only Two-sided Inoculation Lesson 3: Opposing messages(-ers) are a challenge • It can be useful to anticipate and try to offset counter-arguments from opponents of social change • BUT… • Strategies to neutralize the opposition may not work across all social groups • AND… • It’s not always good to wake a sleeping giant AND… It’s not always good to wake a sleeping giant (industry) Source: Harwood et al., 2005 Some Concluding Thoughts Also Need to Consider: Who Delivers the Message? • Traditional news Traditional news • Growing capacity to cover disparities, but • Covering them is still relatively uncommon Also Need to Consider: Who Delivers the Message? • Traditional news • Novel messengers Novel Messengers • Violating expectations of a source can be powerful • Partisan labels increase policy support when they take an unexpected position on a partisan issue • E.g., Republican endorsing same-sex marriage • E.g., Democrat opposing abortion rights Source: Bergan (2012) Novel Messengers Military leaders speaking to policymakers and the public “When it comes to children’s health and our national security, retreat is not an option.” “Retreat is Not an Option: Healthier School Meals Protect Our Children and Country” What We Need to Know • Need more work on the messenger • Need more work on actions vs. opinions/perceptions – What are the actions that individuals can take to influence policy? Direct Democracy in CA and Other Places… But Limited Results The Policy Process is Complex… Source: Bulletin of the WHO (2006) BUT Changes in Public Sentiment can Set the Stage for Changes in Policy Source: Gallup (2012) Questions? Comments? Thank you! Contact me at jdn56@cornell.edu