1.-Piper-Rory_-Research-Findings_-Urban-Migration

advertisement

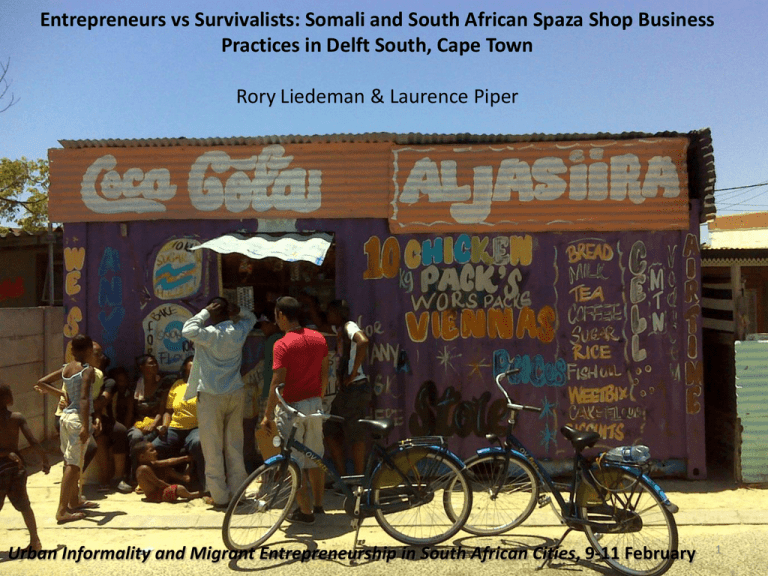

Entrepreneurs vs Survivalists: Somali and South African Spaza Shop Business Practices in Delft South, Cape Town Rory Liedeman & Laurence Piper Urban Informality and Migrant Entrepreneurship in South African Cities, 9-11 February 1 Research Goal • To establish whether the advent of foreign run spaza businesses was due to a particular ‘entrepreneurial’ business model. • To understand ‘the forces’ responsible for supporting this model. Essentially a case study of how social networks enable entrepreneurialism amongst Somali but not South African traders in Delft South, Cape Town. 2 Background • 2011 Sustainable Livelihoods Foundation (SLF) conducted a larger study mapping and interviewing Spazas in Delft and 8 other sites in CCT, JHB and DBN • Emergent findings from this research included the rise of Somali-run shops in Delft, with market success linked to competition on price etc; perception that Somali operated mor eentreprenurial ways than local ‘survivalists’ (Charman et la 2011) • Notably, economic competition cited as one of the main reasons behind xenophobic attacks in Cape Town (Bseiso 2006, Ndenze 2006a, b). • This project seeks to explore in more qualitative detail these alleged differences in business practices to answer the question, why are Somali spaza shops more successful in Delft? 3 Three key research questions 1. Is there indeed a shift in spaza ownership from South African to Somali shopkeepers in Delft? 2. What are the key business practices and can we speak of two distinct models? 3. What is the significance of social networks and associated business culture to business practices? 4 Site Description and Demographics • Delft South is a mixed race working class suburb located on the Cape Flats in the Western Cape of around 20 000 people • Approximately 60% of the working age population is unemployed • The high street or ‘main road’ and residential areas host a variety of businesses • No shopping malls in Delft South. Spaza shops satisfy an important business service. 5 Spaza shops are second most common businesses Other informal business includes: • Street traders (sweets, chips and vetkoek to school goers and pedestrians) • Green grocers (commonly known as Fruit and Veg traders) • Barber shops and hair salons • Pool and arcade entertainment • Taverns and shebeens 6 Methodology • Primarily an ‘in-depth ethnographic approach’. Some survey work too. • Methods and tools include: – In-depth interviews and oral histories of journeys into South Africa (cumulative note taking and observation = 2-3 hours for each of the 13 individual case studies) – Dictaphone (when allowed) – Field diary, informal conversations observations – Global Positioning System, mapping of spaza landscape • Somali interpreter, crucial to establishing rapport and legitimacy 7 8 9 Findings for research question 1: A major shift in spaza ownership and market share has been observed between May 2011 and June 2012 (ie after the SLF survey). • 12 South African spazas closed – only 5 remain open (decrease from 57% market share to 22%) • Ownership of foreign spazas increase from 13 to 18 – a total market share gain of 31% • With a 23% decrease in the total number of (30 to 23), the market share of foreign spaza businesses increased from 43% to 78% in 13 months i.e. 18 spazas now foreign owned 10 11 12 Findings for research question 2: The change in ownership and market share was a direct result of the emergence, and use of a new, and more sophisticated business model • Evidence of a contrast between a ‘survivalist’ model (slow organic businesses of South Africans) and a large scale ‘entrepreneurial’ model (multiple partnerships and large investment by Somali spaza operators) • ‘Entrepreneurial’ model is primarily based upon being price competitive, made possible through collective investment, procurement and distribution networks. • The research operationalized the concept of ‘business models’ by exploring 5 major categories of the business. 13 Operationalising Business Models Detailed documentation of : 1. spaza establishment process (including ownership, contracts/agreements, labour and employment), 2. capital investment 3. stock procurement behaviour 4. business operation (operating times, banking etc.) 5. mobile distribution to spaza shops (access to transport and spaza product distribution networks) 14 One example: Somali capital investments into spaza business 15 Findings relevant to research question 3: The social networks that South African and Somali spaza owners can access is key to these differences in business practices in Delft South. • Most South African spaza operators limit their ability to grow the spaza network and access ‘social capital’, as the business is not entrusted to others beyond ‘immediate’ family ties. Extended family rarely counts. • In the case of Somali operators, social and business networks, exist and are active in all of the 5 major classifications of spaza business. Assistance is therefore present and available from the outset • Most Somali operators are able grow their spaza networks through both immediate and extended family consisting of clan members and close friends. 16 The study demonstrates: 1) 2) 3) How the socially richer and clan-based social networks of Somali shopkeepers enable a more entrepreneurial business model, whereas South Africans rely on a network limited to the immediate family and approach the spaza business as a supplementary livelihoods strategy. The research also provides new insights into the strategic use of both formality and informality by foreign business people (e.g. banking, rental agreements, business agreements) the significance of spatiality to the spaza economy through the concepts of ‘strongholds’ and ‘neighbourhood economies’; and previously unseen forms of spaza related business, principally around the mobile distribution of spaza stock to retailers in Delft. 17 South African vs. Somali : stock 18 Participant 50mSom02 offloading spaza products to a Somali shop in Delft South. Owns a spaza shop in Elsies River and is also a partner of another spaza business based in Gugulethu. The transportation business generates an additional R5000 per month. 19 Mobile Distribution: Popular ‘value pack sausage’ and pies (background) sold by Somali, Pakistani, Burundi, Malawi and Egyptian agents. 20 ‘High top’ canopies are popular as they provide additional spaza to stock spaza products. They are widely used in the trade by individuals in ‘stock transportation’ and ‘mobile distribution’ networks. 21 Contraband cigarettes are key factor in the success of many foreign run spaza shops. The existence of the 50c ‘loose stick’ is ubiquitous in the Delft area 22