OIPRC Webinar - Ontario Injury Prevention Resource Centre

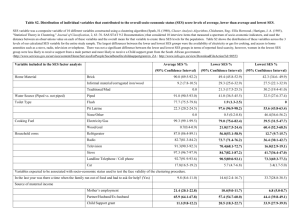

advertisement

The Effectiveness of Interventions Addressing the Social Determinants of Injuries: What do we think we know? What do we still need to find out? (Work in progress) OIPRC Webinar January 25, 2012 Brian Hyndman, MHSc. Senior Planner Health Promotion, Chronic Disease and Injury Prevention Section, Public Health Ontario Health inequities • Differences in population health status are primarily attributable to population-level disparities in the social determinants of health, including income, social status, education, and employment. • The 2008 report by the Canadian Senate Subcommittee on Population Health¹ concluded that about 50% of health outcomes are attributable to social-economic factors ¹ Keon, W. J., and Pepin, L. (2009) A Healthy Productive Canada: A Determinant of Health Approach Ottawa: The Senate Subcommittee on Population Health SDOH and Preventable Injuries: Key Questions 1. What are the socio-economic determinants of health that are most likely to directly or indirectly affect injury/injury rates in Canada? 2. What is known about the mechanisms by which these determinants affect injury rates? 3. What is known about the effectiveness of interventions, including programs, policies and social marketing campaigns, aimed at preventing injury through addressing one or more of the underlying social determinants of health? 4. What are the key gaps in the literature linking injuries to the social determinants of health as well as the literature on the effectiveness of interventions aimed at preventing injury through addressing these determinants? * Builds on findings of 2006 SMARTRISK Environmental Scan commissioned by CIHI 5 Factors Included in Literature Search* Measures of SES Life Course Cross-Cutting Issues Income Children Gender Education Youth/Adolescents First Nations/Inuit/Metis Occupational Status Adults Diversity/culture Others (e.g., deprivation measures, eligibility for targeted supports) Older adults/seniors Geography (urban, rural, remote) * Based partially on SmartRisk (2006) framework 6 Databases searched • Medline • Pyschinfo • Embase • Cochrane 7 Inclusion/Exclusion Criteria for Journal Articles • Published from 2000 – • Focus on studies with Canadian content; studies with content from other countries included ONLY if part of a systematic review/metaanalysis OR focused on strategies applicable to Canadian context • Did NOT include intentional injuries/suicides • Used critical appraisal tool for public health research developed by Heller et al. (2008) to determine studies for inclusion 8 Eligible Study Designs 1. Systematic reviews, syntheses and meta-analyses 2. Before/after studies 3. Controlled trials 4. Observational studies: prospective and retrospective cohort studies, case control and cross-sectional studies 9 Injuries and SES: what the literature tells us • Generally, low SES groups have higher rates of injuries, which tend to be of greater severity and more often fatal • Strength of inverse relationship between SES and injuries varies according to injury type and indicator of SES chosen Exceptions to Inverse Gradient B/W Injury and SES • No clear relationship during adolescent years (a period of greater risk taking among young people across all socio-economic strata) • Higher SES groups at greater risk of sports/recreational injuries 10 Injury Hospitalizations and SES: Age Standardized Rates by Neighbourhood Income Quintiles (Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2010) Injury Hospitalizations and SES: Unintentional Falls (CIHI, 2010) Injury Hospitalizations and SES: Motor Vehicle Traffic Injuries (CIHI, 2010) Significance of relationship between Injury and SES “These differences in (injury hospitalization) rates imply that if every socio-economic group had experienced the same rate as the most affluent group, the national injury hospitalization rate could have been 8% lower. In other words, there would have been about 21,000 fewer injury hospitalizations in Canada.” Canadian Institute for Health Information (2010, p. 2) 14 Explanatory Factors for the Relationship between SES and Injury* Individual Factors • Differences in knowledge and beliefs about potential sources of injury • Differences in health behaviours • Fewer economic resources to buy appropriate safety devices • Greater exposure to hazards • Organization of Work and Occupational Exposure • Psychosocial – (e.g., poverty-related stressors, social isolation) Family-Related Factors • Parental knowledge of child development and abilities • Greater family size/single parenthood (could influence level of supervision) Community/Social Factors • Greater exposure to hazardous environments • Poor access to servicers • Social environment/culture/norms * Source: Alberta Centre for Injury Control Research (2006) 15 Injuries and SES: Implications for Interventions What the Literature tell us • Lack of evidence on nature of the mechanisms underlying socio-economic differences in injury morbidity and mortality • Vast majority of interventions focus on improving the knowledge and practices of “high risk” groups (presumably because broader determinants viewed as less amenable to change) • Majority of interventions focus on childhood injuries (in the home or traffic environment) • Limited evidence that interventions targeting more vulnerable populations are more effective at preventing injuries than population-level approaches; in fact, some studies show that disadvantaged groups receive a greater proportional benefit from populationlevel approaches (e.g., bicycle helmet legislation) 16 East York, Ontario Bicycle Helmet Study (Parkin et al., 2003) % of Children Observed Wearing Helmets before and after Mandatory Helmet Law 90 80 70 60 50 40 Low-Income Areas 30 Mid-Income Areas 20 High Income Areas 10 0 Pre-legislation (1995) Postlegislation (1996) 17 Injuries and SES: Implications for Interventions What the Literature DOES NOT tell us • At the population level, effective injury prevention programs are comprehensive and multi-faceted (i.e., the “three Es”: education, engineering and enforcement). Unclear to what extent these programs are reducing (or potentially exacerbating?) socio-economic inequities in injury outcomes • In summary, existing studies provide a poor evidence base on how best to avoid – or narrow – socioeconomic differences in injury risk; it’s unclear what approaches to prevention work best where it’s needed most 18 Conclusions • More research on mechanisms by which SES may influence injury risk to guide development of effective programs and policies • Need to determine impact of comprehensive, multi-component approaches to injury prevention, which have been shown to be effective at the population level, on disadvantaged groups – will help to determine optimal balance between targeted approaches, population-wide programs/policies and targeted universalism • Advocate to reduce social inequalities contributing to injury inequalities 19 Questions? 20