The art of writing an introduction—for thesis and papers

advertisement

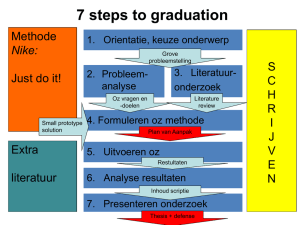

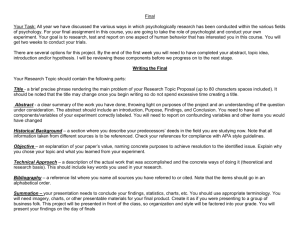

The art of writing an introduction—for thesis and papers Dr. Corum An introduction should do the following things: • • • • • Tell the reader simply and clearly what the subject is. Tell the reader why the subject is important Tell the reader how you are going to approach the subject i.e. the methodology of the author. There are several elements to this. What questions is the author going to ask? What questions will not be asked? The material that the author will use. How the material is pertinent to the subject. What books/secondary sources will be used and why they will be used. In short, the reader ought to know that the work is based on serious research. This establishes the author’s credibility. How the thesis is an original contribution. The author ought to briefly review the major literature on the subject and explain how this work is not covered by existing works. For example, the author might use well-known material and ask new questions or approach an old subject with new questions. Perhaps the author is using new material. In any case, this part explains the need for this particular work. The author expresses his goal in writing the thesis. This could be developing ideas to help determine doctrine or to see if a better way might be found to solve an acknowledged problem. A few other rules: Mostly about argumentation. • Do NOT frontload your thesis. I.e. “This thesis is to tell the world that the USAF ought to get 99% of defense spending”. If you start your research with a conclusion and then gear all of your work to proving your conclusion- then you will have no credibility. • You should not be absolutely sure of your conclusion when you start your thesis. A really good thesis is one that objectively analyzes the material and often leads the author into ideas, solutions and conclusions that he never expected when he started. If the material shows that some of the author’s preconceived notions are faulty, then the author ought to follow the evidence and revise his thinking. Use proper argumentation • Do not set up a straw man – some unnamed people who have dumb ideas – and characterize the opposition as such. It’s phony to shoot down a straw man. • Avoid sweeping language and generalities. Please. • Opposing arguments need to be examined in turn, objectively analyzed and their strong and weak points noted. A thesis that openly and objectively deals with different approaches in a fair manner and borrows good ideas from the various approaches is one that will have a lot of credibility. • The author needs to discuss the strong and weak aspects of his approach to the subject. chapters • A thesis should be about 5-6 chapters – with the first chapter being the introduction, the next 3 chapters the examination of evidence and arguments and the final chapter being the author’s conclusion. In fact, the conclusion ought to flow from the evidence and argumentation of the previous three chapters. A few points on writing an introduction for a BDCOL paper. • A standard 10-page paper ought to have a one-page introduction. Try for three paragraphs. The first paragraph should be short and snappy and be no longer than 4 sentences. You can go into detail in the 2nd paragraph. More on Introduction • The main points in introducing an essay or paper are the same as the main points of a thesis introduction: Tell the reader what you are going to write about, Tell the reader how you will approach the subject, i.e.—what questions are you going to ask, what framework you will use etc. . • Then you will point out the expected result of your paper—come to some lessons about leadership, decision making effectiveness etc. • As with a thesis intro—do NOT tell the reader up front what the conclusions are. Simple • The conclusion should be about 1 page. Keep it direct and simple. For example, “there are three major lessons to be learned about organizational decision making from studying the air war over Kosovo in 1999…”. Then discuss each in turn. Other tips • One trick I have leaned in making the transition to different themes in a paper is to use subheadings. I assure you, the reader finds it helpful. • A final tip. From now on—try NOT to write a paper solely for the course director. Think of a broader audience (USAF field grade officers or airlifters or whatever) and explain the subject in a manner that someone who had not taken the course can understand. It’s good practice to learn to write for a broad audience. Learn to do that well and you might get a few things published. •