Class 20 - Donald J. Kochan

advertisement

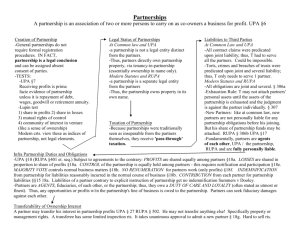

Agency & Partnership Professor Donald J. Kochan Class 20 Today’s Materials Partnership Operation Pages 581-616 Partnership Generally Why enter into a partnership? Pooling of assets Pooling of Expertise Specialization Issues Liability Controls Third Part Confidence – Reputational Marketability Taxation and Bankrupty Issues Saleability/Alienability/Depersonalization Types of Authority What are the types of authority? Why do they matter? Who do they matter to? How do authority issues relate to the incentives to create a partnership? How is the Question related to Control or the Surrender of the same? Know concepts on p. 581 Elle v. Babbitt Implied Actual Authority Case Authority created by acquiescence Ordinary Course of Business BUT, decisions to end the partnership, in effect, require unanimity – i.e. not ordinary course of business Summers v. Dooley Deadlock case – partners equally divided UPA sec 18(e) and (h) (same principles as RUPA 401(j)) UPA 18(h) – “Any difference arising as to ordinary matters connected to the partnership may be decided by a majority of the partners.” -- here have 2 partners and one objects -- focus on word “decided” which does not clearly state need a majority to act Court interprets as Ordinary matters decision requires approval by majority of partners and ½ is not a majority – “If the partners are equally divided, those who forbid a change must have their way.” Consider the indemnification issues separately National Biscuit Co. v. Stroud Focus on first rule – generally, ABSENT restrictions in the partnership agreement, a partner has the power to bind the partnership in any matter legitimate to the business. Alternative phrasing re “ordinary” matters Deadlock case Unpaid creditor/partner objects to continued purchase of bread Court interprets as – unless a majority OBJECTS, ordinary matters may be conducted Probably the better interpretation than Summers as it encourages business to continue in an orderly way AND objecting partner can seek dissolution Apparent Authority and Burns v. Gonzalez Partners have apparent authority to conduct ordinary business and carry on business in the usual way “Usual way” defined according to industry, customs, practices, etc. -- fact specific and context specific; reference to evidence of other firms in the same business is focused on by court Note the parallels with apparent authority in agency discussed on pp. 591-92 In particular, “B is liable for the act of C if B has ‘held out’ to other persons that C is empowered to perform acts of that particular nature” Being “necessary” is not an exception if it is unusual Apparent Authority and Burns v. Gonzalez Burden is on the participating partner to prove what he did was the usual way UPA sec 9(1): Usual Way is based on fact that every partner is the agent of the partnership for the purpose of its business UPA UPA sec 9: (1) Every partner is an agent of the partnership for the purpose of its business, and the act of every partner, including the execution in the partnership name of any instrument, for apparently carrying on in the usual way the business of the partnership of which he is a member binds the partnership, unless the partner so acting has in fact no authority to act for the partnership in the particular matter, and the person with whom he is dealing has knowledge of the fact that he has no such authority. (2) An act of the partner which is not apparently for the carrying on of the business of the partnership in the usual way does not bind the partnership unless authorized by the other partners. (3) Unless authorized by the other partners or unless they have abandoned the business, one or more but less than all the partners have no authority to: (a) Assign the partnership property in trust for creditors or on the assignee's promise to pay the debts of the partnership, (b) Dispose of the goodwill of the business, (c) Do any other act which would make it impossible to carry on the ordinary business of a partnership, (d) Confess a judgment, (e) Submit a partnership claim or liability to arbitration or reference. (4) No act of a partner in contravention of a restriction on authority shall bind the partnership to persons having knowledge of the restriction. Notes on Pages 594-596 Understand RUPA 303 and the filing of a “statement of authority” Gives notice Can expand or restrict Provides greater clarity for otherwise uncertain situations Understand the restrictive attitude taken regarding transfers of real property discussed in note 2 Understand UPA/RUPA word change and note 5 explaining no major difference in substantive rule between “usual way” and “ordinary course” RNR Investments Limited Partnersghip v. Peoples First Community Bank RUPA case where partnership agreement LIMITS authority but third partner never examines the partnership agreement Focuses on the knowledge and reliance point – reliance is reasonable under RUPA if 3 does not have actual knowledge of the lack of authority (UPA has just said “knowledge”); under RUPA, 3 may be put on notice of lack of authority but not have actual knowledge RNR Investments Limited Partnersghip v. Peoples First Community Bank “the determination of whether a partner is acting with authority to bind the partnership involves a two-step analysis. The first step is to determine whether the partner purporting to bind the partnership apparently is carrying on the partnership business in the usual way or a business of the kind carried on by the partnership. An affirmative answer on this step ends the inquiry, unless it is shown that the person with whom the partner is dealing actually knew or had received a notification that the partner lacked authority. See Kristerin Dev. Co. v. Granson Inv., 394 N.W.2d 325, 330 (Iowa 1986)(applying Iowa version of UPA). Here, it is undisputed that, in entering into the loan, the general partner was carrying on the business of RNR in the usual way. The dispositive question in this appeal is whether there are issues of material fact as to whether the Bank had actual knowledge or notice of restrictions on the general partner's authority. [7] RNR argues that, as a result of the restrictions on the general partner's authority in the partnership agreement, the Bank had constructive knowledge of the restrictions and was obligated to inquire as to the general partner's specific authority to bind RNR in the construction loan. We cannot agree. Under section 620.8301, the Bank could rely on the general partner's apparent authority, unless it had actual knowledge or notice of restrictions on that authority. “ Partner Liability by Estoppel and Royal Bank v. Weintraub Post-dissolution behavior of former law partners Case itself is difficult to follow and poorly written Focus on UPA sec 16 -- text on page 604 Fact of dissolution was not readily knowable Partnership by estoppel “should not be lightly invoke and generally presents issues of fact . . .” Here there was an apparent existing partnership and investigation was sufficiently completed In light of notes following, think about risks of continued holding out and other behavior that supports false public impressions or fails to correct such false impressions Bardon Hypothetical Focus on the precise language of sec 16 to determine issues of liability How does consent to use of name fit in? Holding out issues Knowledge issues Implied consent issues Is There a Duty to Speak? Must one act to correct impressions that he did not create? See Official Comment to UPA 16 on page 605: “It has been held that a person is liable if he has been held out as a partner and knows that he is being held out, unless he prevents such holding out, even if to do so he has to take legal action . . . On the other hand, the weight of authority is to the effect that to be held out as a partner he must consent to the holding and that consent is a matter of fact.” So? Brown v. Gerstein Medical Malpractice case and name on letterhead Note the focus on facts and degree Use of name in the business alone too “slender” to show consent even if use of name is with person’s knowledge Case seems to strongly favor actual consent; more egregious facts lead some courts to go other way Brown v. Gerstein See general estoppel elements on p. 607 “to prevail under this doctrine a plaintiff must prove: (1) that the would-be partner has held himself out as a partner; (2) that such holding out was done by the defendant directly or with his consent; (3) that the plaintiff had knowledge of such holding out; and (4) that the plaintiff relied on the ostensible partnership to his prejudice. Ibid. See also Reuschlein & Gregory, Agency and Partnership § 198 (1979); Crane & Bromberg, Partnership § 36 (1968); Rowley on Partnership 423-436 (2d ed. 1960); Painter, Partnership by Estoppel, 16 Vand.L.Rev. 327 (1963). Failure to establish any of these requirements precludes recovery on an estoppel theory.” J&J Builders Supply v. Caffin Masonry building materials delivery case Looking at facts here, court decides Failure to deny statements, coupled with later admission that he had held himself out as a partner (plus but not necessary factor), sufficient to establish liability under UPA sec 16 Personal appearance issue distinguishes case from Brown Reliance Conundrum and Brown & Bigelow v. Roy License on a wall at office case “public representation” Court holds reliance NOT necessary to prove if a holding out is made to the public But see Simonelli Reisen Lumber & Millwork Co. v. Simonelli – and RUPA solves ambiguity Construes UPA 16 as requiring reliance Note 5 on page 616 – RUPA 308 makes clear that reliance is necessary whether the representation is public or private