Business Associations (Sokolow) PART ONE— The Partnership

advertisement

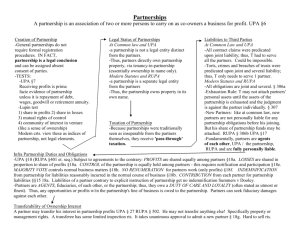

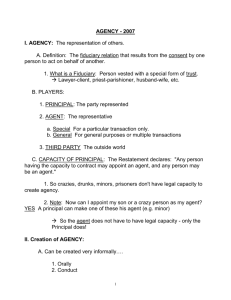

Class Notes— Business Associations (Sokolow) PART ONE— The Partnership (Unincorporated Business Forms) A. General Partnership; Overview and Introduction General Class Information • Professor Sokolow’s Office Hours: o Monday-Wednesday, 9-10am and by appointment o Office 4.114 (take stair 7 by the auditorium) o Office phone number: (512) 232-1379 • Assistant: Nancy Bennett, office 3.240 I. Notes on Structure of Class • Our section of the classroom will be “on call” during the fourth week of class. • * The material in this class tends to be cumulative, so it is very important that you do not fall behind! • The course material is primarily based on statute, rather than case law. The class involves the practical application of law by looking at business relationships. • Statutes: o UPA (1914): Uniform Partnership Act ! Designed to be adopted verbatim o RUPA (1997): Revised Uniform Partnership Act o MBCA (1984): Model Business Corporation Act ! Designed to be used as a model, rather than being adopted verbatim. ! Important note: The MBCA was not adopted by some commercially significant states, such as California, New York, and Delaware. • Note: When reading the statutes, focus on: o Verbs o Conjunctions o “Flip words” ! I.e. Unless, except, etc. • Information on the final exam o The articles in the supplement are fair game for the exam. However, the questions on these articles will generally track the headlines, rather than focusing on the minutiae. o The exam will focus on the statutes and points covered in class, not the facts and details of the individual cases. ! For example, you may get a hypo where an element of the partnership is varied in the partnership agreement, but this particular element can only be varied in the articles (so you need to know the statute!) ! 1 ! Although you do not need to know particular case names, you should be familiar with the noteworthy cases of historical importance, i.e. Meinhard v. Salmon, Donahue v. Rodd, Galler v. Galler, Davis v. Sheerin, etc. o Structure of the exam ! There will be 125 true/false questions, and 45 multiple choice questions • For the true/false questions, you will get +1 point for each correct answer, –1 point for each incorrect answer, and 0 points for leaving the question blank. o So it is important to be strategic for the true/false questions (you will be penalized for wrong answers). • For the multiple choice questions, there is no penalty for incorrect answers. So in this section, you should answer every single question— even a guess is better than leaving it blank! ! You will have 240 minutes to complete 170 questions, so that gives you about 1.5 minutes/question. • (Generally people do not feel rushed or run out of time on this exam). ! There will be roughly 1–2 questions from each class. ! * You are permitted to bring a tabbed and hand–annotated statutory supplement with you into the final exam. o Exam Statistics ! Last year, the maximum score was 170— the highest score was 158 and the lowest score was 15 (that was an “F” grade). The median was 100, so even an 84/170 ended up getting a B+. o There are sample questions and answers at the back of your supplementary materials. II. Types of Business Associations • Unincorporated [25% of course] o Sole proprietorship ! A sole proprietorship is an unincorporated business with a single owner. • Legally there is almost no distinction between the individual and the business. o Partnership ! A partnership is an association of two or more individuals to carry on as partners a business for profit. ! Types of partnerships: • GP: General Partnership • LLP: Limited Liability Partnership • LP: Limited Partnership • LLLP: Limited Liability Limited Partnership o LLC: Limited Liability Company o Note: The LLP and LLC are relatively new business forms that have become very popular. • Incorporated [75% of course] o Corporations ! 2 ! ! Closely-held Publicly-held [50%] [25%] III. ABA Journal— The Strategic Lawyer • Five issues that present themselves in almost every business contract (last column of article): o Money o Risk o Control o Standards (through contract wording) o End game • Lesson here is that it is important for attorneys to be strategic about risk, not just avoid it altogether. • Note: When you read a case, act like a pathologist. What is the problem that arose in this case, and how could it have been avoided? IV. AB Hypo • Facts: A contributes $100,000, B contributes nothing. B is to manage the business, A wants veto power. The profits are to be split 50/50 after B is paid $5,000/month ($60,000/year). o What type of business association have A and B formed in this hypo? ! A and B have formed a general partnership (because they did not file any forms with the state). • The general partnership is the default for a business with more than one owner, because the others all require filing papers with the state. • A general partnership has five elements: o 1) Association ! The association does not have to be voluntary. A court can find an inadvertent partnership, even if the parties never intended to form one. o 2) Of two or more persons ! The term “persons” includes corporations and other entities. o 3) To carry on ! This may be only a specific task, or an ongoing activity. o 4) As co-owners ! See UPA (1914) § 6 to determine if someone is a co-owner. Involves questions such as whether the person received a share of the profits, whether he or she had a right to exercise control over the business, etc. o 5) A business for profit • Note: A “joint venture” is exactly like a general partnership. The difference is that a joint venture requires an express agreement as to how the partners will share the losses (at least in Texas. V. AB Software Store Hypo, continued ! 3 • • ! Facts: A contributes $100,000, B contributes nothing (contribution). B is to manage the business, A wants veto power (control). The profits are to be split 50/50 after B is paid $5,000/month ($60,000/year) (profits and compensation). The five elements of a general partnership (UPA [1914] § 6): o 1) Association o 2) Of two or more persons o 3) To carry on o 4) As co-owners ! How do you determine if an individual is a “co-owner”? • Under UPA (1914) § 7(4), “the receipt by a person of a share of the profits of a business is prima facie evidence that he is a partner in the business, but no such inference shall be drawn if such profits were received in payment: (a) as a debt…, (b) as wages of an employee…” • But note § 7(3), which states that “the sharing of gross returns does not of itself [emphasis added] establish a partnership, whether or not the persons sharing them have a joint or common right or interest in any property from which the returns are derived. o What is the difference between gross receipts and profits? ! Gross receipts looks at total sales, but profits looks at sales minus expenses. Profits are what is left over after rent, utilities, salaries, etc. • Also look at whether an individual has the right to exercise control over the business (whether they choose to exercise that right or not). o Other factors may also be considered when making the determination of whether someone is a co-owner, including the name of the business and how the business filed tax returns (what form). ! For example, the name “AB Software Store” in this case suggests that both A and B are co-owners of the business. • Revisit the idea of an “inadvertent partnership” o Casebook, p. 40: “…a general partnership can be created even if the partners do not realize that they are forming such an enterprise.” o UPA (1997) § 202(a) (analogous to § 6(1) in the 1914 version): “Except as otherwise provided in subsection (b), the association of two or more persons to carry on as coowners a business for profit forms a partnership, whether or not the persons intend to form a partnership. ! Whether someone is a co-owner is a fact-specific inquiry, determined by looking at the presumption and “safe harbor” exceptions set out in § 7(4). o 5) A business for profit 4 • ! Assuming A and B created a general partnership (the other alternative being that A is the sole proprietor and B is an employee), did they accomplish what they wanted (the terms of their agreement)? o Control: B is to manage the business, A wants veto power. ! UPA (1914) § 18(e): “All partners have equal rights in the management and conduct of the partnership business.” • But remember that these are only default rules! The beginning of § 18 says “The rights and duties of the partners in relation to the partnership shall be determined, subject to any agreement between them, by the following rules…” o You need to know the rules of the statute (the default) so that you can draft around them. ! As contrast, look at RUPA § 401 (analog to § 18). § 401(a) says “each partner has equal rights in the management and conduct of the partnership business.” • However, there is no language that says this rule is subject to agreement otherwise. Would this make sense from a policy standpoint? o Note that part of the modernization of RUPA is that this “subject to agreement otherwise” language is simply included once in § 103, rather than the drafters having to repeat the same exception over and over in each section. o Profits and compensation: The profits are to be split 50/50 after B is paid $5,000/month ($60,000/year). ! As a default, UPA (1914) § 18(a) says that partners split the profits equally (as does the analog, § 401). • So here there is no problem. But remember that if there were, you can always contract around the default rule if the partners agree to a different arrangement. ! UPA (1914) § 18(f): “No partner is entitled to remuneration for acting in the partnership business, except that a surviving partner is entitled to reasonable compensation for his services in winding up the partnership affairs.” • So the default rule suggests that B is not entitled to the $5,000/month. However, the default rule is subject to modification, so the $5,000/month is okay. o Contribution: A contributes $100,000, B contributes $0. ! UPA (1914) § 18(a) says that a partner is entitled to be repaid his contributions, but does not say that a partner is required to make a monetary contribution in the first place. • Remember that partnerships are often formed because one person has the financing and the other person has the expertise. ! Can A limit his liability to the $100,000? • A and B did not file the proper forms with the state, so both A and B are jointly and severally liable as to third parties. 5 • • • Remember that it is only in a general partnership that partners have unlimited personal liability as to third parties for the debts and obligations of the partnership. o Sokolow: This is by far the worst aspect of a general partnership. UPA (1914) § 15 says that the nature of the partner’s liability varies depending on whether the action arises out of tort or contract. o The partners are jointly and severally liable for tort claims, and jointly liable for contract claims. ! Joint and several liability: Liability that may be apportioned either among two or more parties or to only one or a few select members of the group, at the adversary’s discretion. • Thus, each liable party is individually responsible for the entire obligation, but a paying party may have a right of contribution and indemnity from nonpaying parties. o Remember that A may have the right to contribution and indemnity from B, but that right means nothing if B has no assets (does not actually put money in A’s pocket). * So A has not accomplished limited liability, because § 15 has no exception for partners to agree otherwise. o Parties cannot contract to limit a third party’s right to recover against them without that third party’s consent. VI. Partnership Formation • It is important not to think about risk in general, but risks for a specific business or industry. Two considerations: o First, think about the people going into business with each other. ! E.g. A and B in the software store hypothetical. This consideration has to do with personal liability. o Second, think about third parties (the people who do business with the firm). ! Two questions: • Can the third party recover from the firm? • Can the third party recover from the owners? ! These two questions are linked, but still separate. It is also important to remember that third parties can always take steps to protect themselves as well, no matter what type of business association he or she is dealing with. • The rules governing partnership formation are UPA §§ 6 (definition) and 7 (rules for formation). o UPA § 6— “(1) A partnership is an association of two or more persons to carry on as co-owners a business for profit.” ! 6 • ! o UPA § 7— “In determining whether a partnership exists, these rules shall apply: (4) The receipt by a person of a share of the profits of a business is prima facie evidence that he is a partner in the business, but no such inference shall be drawn if such profits were received in payment: (a) as a debt by installments or otherwise, (b) as wages of an employee or rent to a landlord…(d) as interest on a loan…” ! The ability to exercise control over the business is the factor that is most likely to cause a court to conclude that a partnership was formed. ! Note, however, that these rules are not exclusive. It is always a factspecific inquiry as to whether a partnership has been formed. Martin v. Peyton o The nature of the partners’ or partnership’s liability depends on the cause of action being presented. ! Under the UPA: In contract actions, the partners are jointly liable. In tort actions, the partners are jointly and severally liable. • (The statute is extremely generous to tort claimants). ! Under RUPA and Texas law: The partners are jointly and severally liable for all debts and obligations of the partnership, regardless of whether the action arises in tort or in contract. o Issue presented: Were the defendants partners in the business, or just creditors? ! The court held that the defendants were merely creditors (and thus were not personally liable for the debts and obligations of the partnership). • The court reasoned that although the creditors had veto power over speculative investments, they did not exercise control over the dayto-day activities of the business and could not affirmatively bind the partnership (i.e. by signing contracts). o In this case, the creditors’ veto power was not construed as control, but rather simply as exercising the appropriate amount of caution and fiscal responsibility. ! (Assets put up as collateral are designed to provide security to a lender, just in case the borrower is unable to make good on his or her promise). o Review/Final Notes ! Sokolow: The court could have decided the case the other way, but he thinks the decision came out correctly. Why? • There was a great deal of money at stake (the creditors’ contribution was one of significant value). Thus, it makes sense that the defendants would want to exercise a commensurate amount of control. • This particular enterprise also had a history of making risky business decisions. So again, the desire of the defendants to be able to exercise a significant amount of control is not unusual. ! In determining whether someone is a partner, the analysis always starts with UPA §§ 6 and 7. • If an individual is receiving a share of the profits, the presumption is that person is a partner. Starting with that presumption, we then 7 • look at the other factors to see if they negate or override that presumption. o But it is important to note that no such presumption exists under Texas law! Receiving a share of the profits in Texas is just one factor to be considered in the overall analysis. Contrast Martin v. Peyton with Lupien v. Malsbenden (note 3, CB p. 44), where the court held that the defendant was a partner, not a creditor. o In Lupien, the court reasoned that the defendant was deeply involved in business operations, made a loan to the business that was not required to be paid back with interest (so that it looked more like an investment masquerading as a loan), etc. ! This case is another example of where a court may find that a partnership was formed, even when that was not the intention of the parties. o Recall UPA § 7(4)— “In determining whether a partnership exists, these rules shall apply: (4) The receipt by a person of a share of the profits of a business is prima facie evidence that he is a partner in the business, but no such inference shall be drawn if such profits were received in payment: (a) as a debt by installments or otherwise, (b) as wages of an employee or rent to a landlord…(d) as interest on a loan…” ! CB pg. 42 of Martin v. Peyton lists floor and ceiling amounts for how much the creditors are to be paid back. So whether or not there is a presumption in favor of the view that a partnership has been formed by virtue of receiving a share of the profits, remember that it is still necessary to consider the other factors and exceptions (“safe harbors”). The court balances all of the considerations together in order to reach a conclusion. • The idea of reaching a “tipping point” at some point in the analysis. When all of the factors are considered together, the Martin court held that the evidence was insufficient to support the conclusion that a partnership had been formed. VII. The Partnership Agreement • The general partnership is the only type of business association with more than one owner that does not require a filing with the state. A written agreement is not required to form a general partnership, but is generally always a good idea. Why? A written agreement may… o Help avoid future disagreements and conflicts. o Be used to protect a partner’s interest if he or she loans property to the partnership (rather than making an outright contribution). o Be used to allocate tax burdens. ! For example, the IRS requires that tax burdens be allocated in writing, or they will split evenly by default. o To prove a partnership even exists. o To provide an “end game,” or exit strategy. • There are also some reasons why partners may choose not to reduce a partnership agreement to writing: o Cost (hiring an attorney, etc.) ! 8 • • • o The fear that reducing an agreement to writing will create problems that would not have arisen otherwise. ! (The partners’ belief that trying to form a written agreement may ruin the deal by bringing up these hidden issues). Gano v. Jamail (CB notes case) o Sokolow: This case was wrongly decided by the court. A written agreement is only required to satisfy the statute of frauds if there is no way the obligation or partnership could be satisfied within one year. Smith v. Kelley o Smith claims that he is a partner in the business because he wants a share of the profits. ! The court says there is no evidence of his partner status, other than the fact that he was held out to the public as such (he had no authority to hire and fire, make purchases, etc. and never previously claimed to be entitled to a share of the profits). • Thus, the court held that there was no partnership in fact (applying a §§ 6 and 7 analysis). o Determining whether someone is a partner involves two questions: ! Is there a partnership in fact? See UPA §§ 6 and 7. ! Is there a partnership by estoppel? See UPA § 16. • It is important to note that § 16 only applies when the plaintiff is a third party! Partnership by Estoppel doctrine o The partnership by estoppel doctrine only applies when the plaintiff is a third party, because this doctrine does not involve an actual partnership (it is not a form of business association, because you do not form a partnership by estoppel). ! This doctrine applies when a third party is harmed by the public representation that someone is a partner, and is justified on principles of equity and fairness. • The structure of the statute itself also provides a clue that this doctrine only applies to third party plaintiffs (because it is found in part III of the UPA Table of Sections, which governs relations of partners to persons dealing with the partnership. o Also note that the partnership by estoppel doctrine only applies to a contract claim, not a tort claim. ! The doctrine only applies to someone who has “given credit,” suggesting the formation or existence of a contract. • E.g. Klein and Graham’s public representation that Smith is a partner is not sufficient to bind him as such unless Smith consents to that representation. o Smith’s consent to this representation may be express or implied. VIII. Agency Law— Tort Claims • We will focus on two different areas of agency law: o Tort claims ! 9 • • ! o Contract claims ! (This is where we will spend the majority of our discussion). In tort claims, tortfeasors are always liable for their own torts. Under agency law, the question is whether the injured third party will be able to bring a tort claim against the employer for the employee’s tort (referred to as vicarious liability or respondeat superior). o Respondeat superior (meaning “let the superior make answer”) is the more general term. This doctrine holds an employer or principal liable for the employee's or agent's wrongful acts committed within the scope of the employment or agency. o Vicarious liability is liability that a supervisory party (such as an employer) bears for the actionable conduct of a subordinate or associate (such as an employee) based on the relationship between the two parties. o (Both theories are designed to protect the innocent third party by tipping the scales against the wealthy master). There are two requirements that must be met in order for the principal (employer) to be held liable for the employee’s wrongful acts under a theory of vicarious liability: o 1) Is the actor (employee) a servant? ! E.g. An independent contractor is not a servant. ! To determine whether an employee is a servant or an independent contractor: • The most important factor to be considered is whether the employer has the right to control the way the employee actually (physically) does the job, whether that right of control is exercised or not. o 2) Is the actor (employee) acting within the scope of his employment? ! If the employee is performing the task for which he was hired to perform, he is clearly acting within the scope of his employment. ! “Detour”: When a servant makes a minor deviation from his ordinary job task(s). In this case, the employee is generally still considered to be acting within the scope of his employment. ! “Frolic”: When a servant makes a major deviation from his ordinary job task(s). In this situation, the employee is not considered to be acting within the scope of his employment. • Hypo: An Austin law firm hires a driver to deliver documents to the court. On his way to the court, the driver instead takes a detour to Leander to meet friends for drinks. o At this point, the employee would be on a “frolic,” and would no longer be acting within the scope of his employment so as to make the employer liable for his wrongful acts. o If both conditions are met ([1] The actor/employee is a servant, and [2] The actor/employee is acting within the scope of his employment), then the employer and employee are both jointly and severally liable. 10 ! An injured third party is likely to go after the master, who tends to have deeper pockets. The master then has the right to indemnification from the employer, but that depends on the employee having any assets. o [Note that the most recent version of the Restatement does not use this terminology, but all of the case law does]. IX. Agency Law— Contract Claims • [Recognize that agency law has an importance outside the context of business associations]. • (The terminology in a contract claim is that of principal, agent, and third party. An agent enters into a contract with a third party, acting on behalf of a principal). o Usually, the third party is trying to enforce a contract against the principal. What the third party will have to prove is that the agent had apparent or actual authority. • Actual authority exists when the agent has direct permission or instruction to act on the principal’s behalf. This authority is conveyed by the principal, and may be either express or implied. o Express actual authority ! Example: “Go out and buy these books and charge them to my account.” o Implied actual authority ! Implied actual authority is granted when the agent implies that he or she has the authority to act on the principal’s behalf based on the principal’s past conduct. • Example: If the principal pays for all of the book bills without objecting (even if he also never expressly authorizes the purchases), then the agent can reasonably infer that continuing to buy books on the principal’s behalf in the future is an authorized action. o (In these situations, what constitutes a reasonable inference or understanding is determined from the agent’s point of view). • Apparent authority exists when the principal misleads a third party to believe the agent has the authority to act on his behalf. o Apparent authority is not really authority at all! But the principal may be bound based on estoppel (concerns for equity and fairness), because of the innocent third party’s reliance on that representation. ! Example: If the agent comes back with the books and the principal pays for them but says never charge anything to my account again. The agent now knows that he or she has no authority to act on the principal’s behalf, but apparent authority may still exist in the mind of the Co-Op (who never heard the principal make that statement). Because apparent authority exists in the minds of third parties, it is much more difficult to destroy (because the principal would then have to go to each third party and tell him/her that the agent is in fact not authorized to act on his behalf). o Whether the agent had apparent authority is determined based on what a reasonable third party would infer (viewed from the third party’s perspective), even though in fact there was no authority at all! ! 11 ! • • ! This concept is designed to protect the innocent third party, and is based on concepts of equity and fairness. o Apparent authority cannot be based on the agent’s actions alone, because apparent authority is created by the principal’s actions or representations to a third party that the agent is authorized to act on his behalf. ! Hypo: Abel is Professor Sokolow’s research assistant. Abel goes to the Co-Op and tells the cashier that Professor Sokolow (the principal) has authorized Abel as his agent, and that he is authorized to purchase books on Professor Sokolow’s behalf. Professor Sokolow is standing right behind Abel in line and hears him say this to the Co-Op employee. In fact, he has not authorized Abel to act as his agent. However, he says nothing to contradict Abel’s statement. • In this case, Abel has apparent authority in the mind of the Co-Op employee. o A principal can only terminate apparent authority by dispelling the notion that the agent has such authority in the mind of each person that believes the supposed agent holds such power. ! Thus, it is much harder to terminate apparent authority. A principal may terminate actual authority, on the other hand, simply by telling the agent he is no longer authorized to act on the principal’s behalf. ! Class question (exception): If the third party hears from a reliable outside source that the agent actually isn’t authorized at all, then there is no apparent authority and likely no cause of action against the principal. o How can a principal terminate apparent authority? ! Newspaper notice ! Personal notice ! [Note that the idea of apparent authority is based on principles of equity. The principal may not actually be aware of all the third parties who believe that the agent has apparent authority, so simply making a good faith effort to inform all or most of these third parties that the apparent authority has terminated may be sufficient to release the principal from being bound]. When trying to determine whether the principal is bound, first look at whether the agent had actual authority at the time of the contract. If he did, then the principal is bound. o Recall that actual authority can be express or implied (what would be a reasonable inference from the agent’s point of view). ! Express actual authority: An oral or written statement from the principal giving the agent authority to act on the principal’s behalf. ! Implied actual authority: What the agent can reasonably infer is allowed based on the principal’s past conduct. The relevant question in making these determinations is not whether the agent was generally authorized to act on the principal’s behalf, but whether the agent was authorized to take the specific action that he did. o Example [based on the CB example at p. 24]: Peter (the principle) authorizes Abel (the agent) to act as his agent in selling a property. Peter tells Abel not to sell the property for less than $300,000. Abel sells the property to Ben for $275,000. 12 ! • • Is Peter bound by the terms of the contract (sale to Ben)? • The condition imposed by Peter (not to sell the property for less than $300,000) is known as a “secret limitation” on actual authority. This secret limitation on actual authority does not mitigate or reduce apparent authority, because there is no way the third party would have knowledge that Abel is not authorized to sell the property for less than $300,000. o Thus, Abel still has the apparent authority to conduct such a sale from the reasonable perspective of Ben. Even in situations where the agent has no actual or apparent authority, there are substitute or alternate forms of authority that may still exist. For example, ratification. o Ratification of apparent authority must occur at the time of the contract. This type of authority exists in a situation where an agent enters into a contract without any authority at all, but then the principal ratifies the contract after the fact. o In order for the ratification to be valid, the principal must have knowledge of all the material facts relevant to the situation. The principal must also have contractual abilities, both at the time the original contract was formed and at the time of ratification. ! Why? Because ratification is retroactive! Although ratification occurs after the fact, it has the effect of making it as though the principal was a party to the original contract from the very beginning. o A principal who chooses to ratify a contract must ratify the entire document. You cannot have “partial ratification,” where the principal ratifies some parts and not others. Another substitute or alternate form of authority is adoption (an option not included in the casebook). o Adoption occurs when the principal “adopts” the contract as his own later on. Basically, he chooses to accept the contract as if he had initially authorized the agent to take such action. However, adoption is not retroactive! X. The Application of Agency Laws in a Partnership • Always be aware of what the statute says! See UPA §§ 9, 13, 14, and 15 o §§ 13 and 14 address the situation of when a partner commits a tort. When the tort is committed by a partner, we apply §§ 13 and 14 rather than the normal tort analysis. ! A partnership is only liable for a partner’s tort if the partner was acting in the ordinary course of the partnership. • Under UPA § 15, “All partners are liable (a) Jointly and severally for everything chargeable to the partnership under sections 13 and 14.” • But recall that under agency principles, a partnership may also be liable for an employee’s tort. In that case, the regular agency analysis applies. o 1) Was the employee a servant? o 2) If so, was he/she acting within the course and scope of employment? ! 13 ! • • • ! If one of these criteria is not met, the employer is not liable. The employee is still personally liable, however, as tortfeasors are always liable for their own torts. The contract liability of a partnership is determined by § 9(1), as well as § 18. o Under UPA § 9(1), “Every partner is an agent of the partnership for the purpose of its business, and the act of every partner, including the execution in the partnership name of any instrument, for apparently carrying on in the usual way the business of the partnership of which he is a member binds the partnership, unless the partner so acting has in fact no authority to act for the partnership in the particular matter, and the person with whom he is dealing has knowledge of the fact that he has no such authority.” ! This section confers both actual and apparent authority on each and every partner, which is an unusual combination. Recall that apparent authority cannot be created by the agent alone (i.e. by the agent saying he has the authority to act for the principal). Apparent authority must be created by an act of the principal himself. o The principal is not liable in the absence of actual and apparent authority. ! Under UPA § 9(1), “Every partner is an agent of the partnership for the purpose of its business, and the act of every partner, including the execution in the partnership name of any instrument, for apparently carrying on in the usual way the business of the partnership of which he is a member binds the partnership, unless the partner so acting has in fact no authority to act for the partnership in the particular matter, and the person with whom he is dealing has knowledge of the fact that he has no such authority.” • The third party cannot rely on the equitable doctrine of apparent authority if he or she knows the agent has no authority to act on behalf of the principal. • Note that § 9 does not explicitly say that it may be modified by agreement. However, courts have universally held that this is the case. o The substantive rules governing the internal affairs of a partnership may generally be altered by agreement of the partners. (CB p. 56, note 6— see RUPA § 103). • Section 9 governs the relationship between third parties v. the partnership v. partners. Section 18 governs the relationship between the partners themselves. Hypo: A, B, and C form a partnership. A is entitled to 60% of the profit, and B and C are entitled to 20% of the profits each. o Section 18(e) says that all partners have equal rights in the management of the business, and these rights are not dependent on each partner’s level of capital contribution or profit share. However, this power distribution can always be modified by agreement between the partners. o Section 18(h)— “Any difference arising as to ordinary matters connected with the partnership business may be decided by a majority of the partners; but no act in 14 • • ! contravention of any agreement between the partners may be done rightfully without the consent of all the partners.” ! The use of the term “majority” refers to a majority in number, not in interest. ! Thus, potential problems may arise in situations where you only have two partners with equal rights of management and control. National Biscuit Co. v. Stroud (CB p. 53) o Facts ! Stroud and Freeman entered into a general partnership to sell groceries. Nothing in the agreed statement of facts indicated or suggested that Freeman’s power and authority as a general partner were in any way restricted or limited by the articles of partnership in respect to the ordinary and legitimate business of the partnership. ! Stroud advised the plaintiff that he personally would not be responsible for any additional bread sold by the plaintiff to Stroud’s Food Center. After such notice, Nabisco sold and delivered read to Stroud’s Food Center at the request of Freeman. o Rules/Reasoning ! All partners have the power to bind the partnership in any manner legitimate to the business (§ 9). ! All partners are jointly and severally liable for the acts and obligations of the partnership. ! Under UPA § 18(h), Stroud (Freeman’s co-partner), could not restrict the power and authority of Freeman to buy bread for the partnership as a growing concern, for such a purchase was an “ordinary matter connected with the partnership business,” for the purpose of its business and within its scope… • By definition, one person in a two-person partnership cannot be a majority. o Holding ! The Court found that under UPA § 9, Freeman had actual authority to bind the partnership in this case. o Notes ! The starting point in Nabisco is the premise that Freeman has actual authority to bind the partnership in this manner, and that Stroud cannot deprive him of this authority (based on the default rules in the statute). ! Under UPA § 9, a partner has authority to bind the partnership for any act that is “apparently carrying on in the usual way the business of the partnership.” It is unclear whether it would also encompass an act that is not within the apparent course of business of the partner’s firm, but that is within the apparent course of business of other firms engaged in a similar line of business. There is authority under UPA for this broader construction. Summers v. Dooley (CB p. 51) o Facts 15 ! o o o o ! This case involves a claim for reimbursement by one partner against the other, for expenses incurred for the purpose of hiring an additional employee for their trash collection business. ! When Summers initially approached Dooley regarding the hiring of an additional employee, Dooley refused. Nevertheless, on his own initiative, Summers hired the man and paid him out of his own pocket. Plaintiff-Appellant’s argument ! In spite of the fact that one of the two partners (Dooley) refused to consent to the hiring of additional help, nonetheless, the non-consenting partner retained profits earned by the labors of the third man and therefore the non-consenting partner should be estopped from denying the need and value of the employee, and has by his behavior ratified the act of the other partner who hired the additional man. Issue ! Whether an equal partner in a two man partnership has the authority to hire a new employee in disregard of the objection of the other partner and then attempt to charge the dissenting partner with the costs incurred as a result of this unilateral decision. Holding ! One person cannot constitute a “majority” in a two man partnership, as is required for ordinary business decisions under UPA § 18(h). • Section 18(e) bestows equal rights in the management and conduct of the partnership business upon all of the partners (subject to agreement otherwise). • One partner cannot bind the partnership, because one person is never sufficient to constitute a majority. o (So in a two-person partnership, you effectively always need unanimous consent?) ! Affirmed— No majority, so no reimbursement for expenses occurred in unilaterally hiring third employee. • Court also relied on the fact that Dooley actively objected, which is more conclusive than if Summers had informed Dooley of his choice and Dooley had done nothing. Case Analysis ! Although most courts have followed the approach in Nabisco, the Nabisco and Summers v. Dooley cases appear to contradict each other. How can they be rationalized? • The plaintiff in Nabisco is an innocent third party, which might be more likely to engender the court’s sympathy. • If Stroud really wanted to protect himself, he would have to dissolve the partnership and provide notice to Nabisco under UPA § 35 (so as to destroy apparent authority). Because he could have protected himself and failed to adequately do so, the court may also be less sympathetic to his situation. ! Recall that the relevant sections for tort liability are UPA §§ 13 and 14. If the tort was committed by a high-level employee, the partnership/company 16 will be liable so long as the employee was acting in the ordinary course of business. o RUPA § 303— Statement of Partnership Authority ! Executing a Statement of Partnership Authority allows a partnership to protect itself against third-party claims. • How? Because the Statement is filed with the state, and thus provides documentary evidence to support the partnership’s future argument that the partner who committed the act in question had no authority to bind the partnership. But note that on closer look, the statement may not do much good at all— the level of protection that the statement provides (and thus its effectiveness) depends on the nature of the transaction (whether the action arises from tort or contract law). o For real property, the partnership is shielded so long as the document was properly executed and filed with both the Secretary of State and the county recording office where the real property is located. ! Filing the document in the county recording office is a necessary requirement because it is sufficient to put a prospective buyer on constructive notice. • However, any limitation on a partner’s authority is only binding on a third party if that third party had actual knowledge of the restriction (this limitation applies to the sale of anything other than real property, which is governed by the rule above). o It will be extremely rare that a third party will have actual knowledge in these cases, because lay people do not usually check the Secretary of State filings before engaging in ordinary business transactions. ! (On the contrary, buyers of real land are expected to adequately research title). XI. Liability— Overview • There are two separate issues in regards to liability: o Sharing of profits and losses o Liability • Sharing of Profits and Losses o The default rule under UPA § 18(a) is that partners share profits equally. Thus, the partners also split losses equally. ! However, there are a number of alternative possible arrangements that the partners can agree to. For example, partners may agree to a flat percentage basis, or a profit sharing ratio for each partner (established in the partnership agreement itself or by issuing “partnership units” to each partner). [Benefits of using a “partnership unit” arrangement are listed on p. 63 of the casebook]. o So the general rule is that losses follow profits, unless the partners agree to an alternate arrangement (such as the possible options listed above). ! 17 ! • • • • ! If the partners choose an alternate arrangement for sharing profits (i.e. Partner A— 60%, Partner B— 20%, and Partner C— 20%), then that is how the partners will split losses as well. o Note that any agreement is not effective against a third party, but will be effective as an indemnification agreement between or among the partners themselves. o UPA § 18(a)— “Each partner shall be repaid his contributions…” So in the AB Software Store hypo, A is entitled to get his capital contribution back. o But under § 18(f), “no partner is entitled to remuneration for acting in the partnership business…” So B will not be repaid/compensated for his service contributions in the absence of an agreement otherwise. ! Notice that the statute contains an inherent bias in favor of the partner who makes capital contributions (as against the partner who only makes service contributions). So if B wants to make sure that he is protected, they need to “agree otherwise,” and contract around the statute. [Example— See problem on p. 8 of supplementary materials]. Recap of § 18— Partners’ obligations to each other o UPA § 18(a)— “Each partner shall be repaid his contributions, whether by way of capital or advances to the partnership property…” o But under UPA § 18(f), “No partner is entitled to remuneration or acting in the partnership business…” ! So notice that § 18 of the statute clearly creates a preference for the partner contributing capital versus the partner contributing services or labor. Go back to the AB Software Store Hypo— Assume B took the $100,000 from A and went out and spent it on inventory. Before the partners can purchase insurance, however, the inventory is destroyed through no fault of either partner. Does B have to contribute to A’s capital loss? o In § 18(a), the statute seems to suggest that the answer is yes. And in fact, most courts in this case would say that B is required to pay $50,000 to repay A’s capital contribution. ! So the Kovacik Court’s statement on page 67 that a partner who only contributes services is not responsible for contributing towards the other partner’s capital loss is not entirely accurate. At a minimum, this statement is against the majority rule. o However, a court may recognize that the bias in the statute favoring the capitalcontributing partner may yield unfair results. So a court can take two different approaches to avoid the unfairness that would result from application of the statute: ! Find that no partnership exists, or ! Find that there was an “agreement otherwise” (either express or implied), so as to “contract around” the default statute. The Kessler case (discussed in note 4 on p. 69 of the casebook) allegedly involved a joint venture. In reality, however, there is very little practical difference between a joint venture and a partnership. o The Kessler court said “as a general rule joint ventures are thought of in relation to a specific venture, a single undertaking, although the undertaking need not be 18 • • one susceptible of immediate accomplishment…not general in operation or duration.” o A different characterization is that a general partnership is formed to carry on, and a joint venture is formed to carry out. However, a general partnership can also have a limited scope, and a joint venture may be long term. So these characterizations are not always accurate. o The modern view rejects this separate characterization and treats a joint venture simply as a general partnership that has a limited purpose. Under the modern view, therefore, general partnership rules govern the formation and operation of joint ventures. So ultimately, a joint venture is governed by the same rules as a general partnership. The only difference is that a joint venture requires an agreement as to how partners will share losses. XII. Partners’ Personal Liability for a Firm’s Obligations • It must first be determined whether the partnership is liable, because the partners are only liable if the partnership is liable. o Whether the partnership is liable is determined by looking at § 9. Section 9(1) states, “Every partner is an agent of the partnership for the purpose of its business, and the act of every partner, including the execution in the partnership name of any instrument, for apparently carrying on in the usual way the business of the partnership of which he is a member binds the partnership, unless the partner so acting has in fact no authority to act for the partnership in the particular matter, and the person with whom he is dealing has knowledge of the fact that he has no such authority.” • UPA § 15— “All partners are liable (a) Jointly and severally for everything chargeable to the partnership under sections 13 and 14. (b) Jointly for all other debts and obligations of the partnership; but any partner may enter into a separate obligation to perform a partnership contract. o [Idea of “bifurcated liability”]. o To recover from partners who are jointly liable, the third party/plaintiff must join all partners as defendants (must sue all of the partners at once). To recover from partners that are jointly and severally liable, a plaintiff has a choice— he can sue all the partners, just one partner, or several partners. ! If the plaintiff sues just one partner, that partner is responsible for paying the judgment out of his own pocket. However, that person has an indemnification claim against the other partners who were not joined in the suit. However, this indemnification claim only has value if the other partners have assets that can be used to satisfy the claim. • RUPA § 306(a)— “Except as otherwise provided in subsections (b) and (c), all partners are liable jointly and severally for all obligations of the partnership unless otherwise agreed by the claimant or provided by law.” o Texas is a RUPA jurisdiction. o But RUPA § 306(a) must be read in conjunction with § 307, which tries to effectuate a balance through the “exhaustion requirement” in (d). ! 19 ! • • • RUPA § 307(d) says that before a third party can recover from a partner individually, the third party must first exhaust the partnership resources. • This requirement essentially makes partners guarantors of partnership obligations. Note that there is no “exhaustion requirement” in the parallel UPA statutes. When the payment comes from the partnership, it is called indemnification. But when the payment comes from individual partners, it is called contribution. Obviously, the tortfeasor himself is not entitled to indemnification, because he is the responsible party. The tortfeasor is always liable, although the injured party may be able to recover from others as well under agency law principles. o UPA § 15 is very generous to tort claimants. Recap/Conclusion— UPA § 15 o The partnership is liable to a third party claimant if a partner’s actions result in a partnership obligation. For example, P entered a contract with actual or apparent authority to act on the partnership’s behalf. ! If the partnership instructs an agent to go out and enter contracts on the partnership’s behalf, that person is essentially acting as an independent contractor and thus has no personal liability. o Individual partners are personally liable if the partnership is liable. o So there are three questions that must be answered in determining liability. ! Is the individual liable? • (I.e. because he is the torfeasor). ! Is the firm liable? ! Are the partners liable? • (Determined through agency law principles). --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Chart from Supplement (page 7)— Vicarious Liability in Unincorporated Texas Business Associations: A Comparison Business Form Vicarious Liability of Partners/Members Comment General Partnership (GP) Joint and several (“Exhaustion requirement”) Worst aspect of a general partnership. Limited Liability Partnership (LLP) None Like a corporation. Limited Partnership (LP) Joint and several for general partners (unless LLLP); None for limited partners (unless control) Tit for tat for limited partners Limited Liability Company None Like a corporation. ! 20