11. Public goods

advertisement

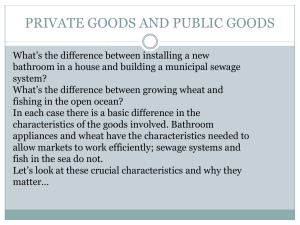

Public Goods Lecture 11 – academic year 2014/15 Introduction to Economics Fabio Landini What do we do today? • Lect. 11: what happens when markets cannot provide a price for goods? • Lect. 11: what’s the difference between private goods and public goods? • Lect. 11: how can we come avoid opportunistic behaviour (free rider)? Common resources • What happens when natural resources finishes (e.g. fish)? • Which countries and/or citizens have to pay for such resources? 3 Public goods • Who decides how much we should spend for the public sector? • What could happen if everyone stop paying taxes? The allocative function of prices In our economic system (private capitalism) most goods are allocated though the market mechanism. For these goods, the price is the reference point for consumers (how much to buy) and producers (how much to sell). Not everything has a price… However, there are also free goods (nice walk in Parco Ducale). For free goods, markets are not good devices to design the allocation of the resources. The price does not reflect the consumers’ willingness to pay. Indeed, the price cannot equalize supply and demand. Not everything has a price… In this case: Public intervention can solve market failure & increase economic welfare. Market efficiency and good typology The efficiency of markets depends on the type of goods. The various goods available in our economy differ along two dimensions Excludability and Rivalry Typologies of economic goods Excludability An individual can be prevented from using a good (e.g. laws usually recognize the private property of a good) Typologies of economic goods Rivalry The consumption of a good by an individual prevents the simultaneous consumption of the same good by other individuals Example of a public good: A bridge A bridge connects two shores of a river Given a certain dimension of the bridge, if the n. of people using the bridge increases (congestion): consumption rivalry If there is a tax for the bridge (those who don’t pay cannot use it): consumption excludability Example of the bridge Many Free access Rival N. people Few Not rival Example of the bridge Tax yes Given number of people No Not Excludable excludable Example of the bridge: two-ways table Many N. people Few Tax Yes No Excludable Not excludable Rival (PRIVATE GOODS) Rival (COMMONS) Excludabe Not excludable Not rival (NATURAL MONOPOLY) Not rival (PUBLIC GOODS) Four types of economic goods (1) Private goods • Both excludable and rival Example: ice-cream, CDs, etc. Public goods • Neither excludable nor rival Example: national defence, scientific knowledge, Wikipedia Four types of economic goods (1) Commons • Rival but not excludable Example: sea fish. Natural monopoly • Excludable but not rival Example: drinkable water Public goods and externalities Non-excludable goods all can benefit without paying the price, p = 0 Access to the good cannot be limited; private value = 0, social value > 0 But: production costs > 0 (scarce resources) Who is it going to produce the good, if not paid? Therefore: positive externalities of a public good (autonomously, market produces too few). The problem of free riding A free rider is a person who can enjoy the benefit of a good without paying the price In order to build the bridge, a voluntary contribution equal to 10 is requested….. The bridge The bridge is is built not built I contribute (I pay 10) 90 - 10 I do not contribute (I don’t pay) 100 0 It is convenient for me NOT to pay!!! Free riding in public transport The problem of free riding Since public goods are not excludable, each individual can refuse to pay the good, hoping that other people will pay in his/her place. If everybody reasons the same, the good is not produced. IMPORTANT: the presence of free riding makes it impossible to rely on the market to supply public goods. Solution of the free riding problem If the benefits > costs (social value > 0), public authorities can produce the good by relying on taxes. Example: fireworks by Moena’s Municipality – 500 inhabitants; value for each inhabitant =10 €; cost of fireworks = 1000 €. – Fireworks tax for each inhabitant = 2€, it covers the costs. – Consumer surplus = 8€ (= 10€ - 2€). The need for a State to produces public goods, whose cost is financed via taxes, represents the main economic justification for the existence of taxation (and thus for the fight against tax evasion): that is the “minimum State”. Common resources Common resources are not excludable They are freely available for anybody to exploit But they are rival: the consumption of the good by one individual reduces the possibility for other individual to consume Examples of common resources • Air and clean water • Congested streets • Fishes, whale and other wild species The tragedy of the commons When an individual, by using a resource, diminishes the availability of the resource for others we encounter the tragedy of the commons. Common resources tend to be overexploited This generates a negative externality. The tragedy of the commons The public administration can: • Impose a tax on usage; • Regulate the use of the resource; • Transform the common resource in a private good (by defining and enforcing individual property rights on the resource). The importance of property rights When the absence of property rights is the cause of market failures, public intervention can potentially solve the problem in 3 ways 1) By defining property rights, which enable the market to operate efficiently; 2) By regulating individual behaviour; 3) By producing a good that the market does not supply. Conclusion Economic goods differ in terms of excludability and rivalry. The market can function when goods are private i.e. both excludable and rival. Public goods are neither excludable nor rival, hence the market does not function well. In because of free riding, it is the public sector who is responsible to supply public goods. Conclusion Collective resources are rival but not excludable. Since individuals do not pay for the use of the resource, there is a tendency toward over-exploitation. Public administration may limit the use of common resources via access regulation and taxes